How Inclusive Placemaking Shapes Riverfront Regeneration?

This article explores how inclusive placemaking can revitalize riverfronts into shared, meaningful spaces that truly belong to everyone. Moving beyond design, it emphasizes co-creating places with local communities, particularly ensuring the inclusion of marginalized groups. Riverfronts, as vital urban-nature interfaces, are often redeveloped without engaging those most affected. Through case studies of Seoul’s Cheonggyecheon River and Cairo’s Al Warrak, the article illustrates both the transformative power and challenges of inclusive processes. Ultimately, it argues that genuine community involvement is essential to creating vibrant, equitable public spaces.

Introduction:

In rapidly urbanizing environments, public spaces design directly affects social cohesion, environmental comfort, and everyday life. Placemaking is an approach that transforms physical spaces into vibrant, comfortable, meaningful, and full of spirit environments molded by and for the community.

Placemaking -in its essence- involves the community as a beneficiary and more importantly as a main contributor in shaping functional spaces with its identity. It supports not only essential needs in people’s lives, including social interactions, accessibility, and place attachment, but it goes beyond that to anticipate future needs according to the study of urban change.

Inclusive placemaking founded on top of this approach to ensure that no group is excluded. It intentionally incorporates underrepresented people to create accessible, representative and well trusted spaces by all. This approach nurtures civic participation, reflects diversity, and reinforces the collective ownership of public space.

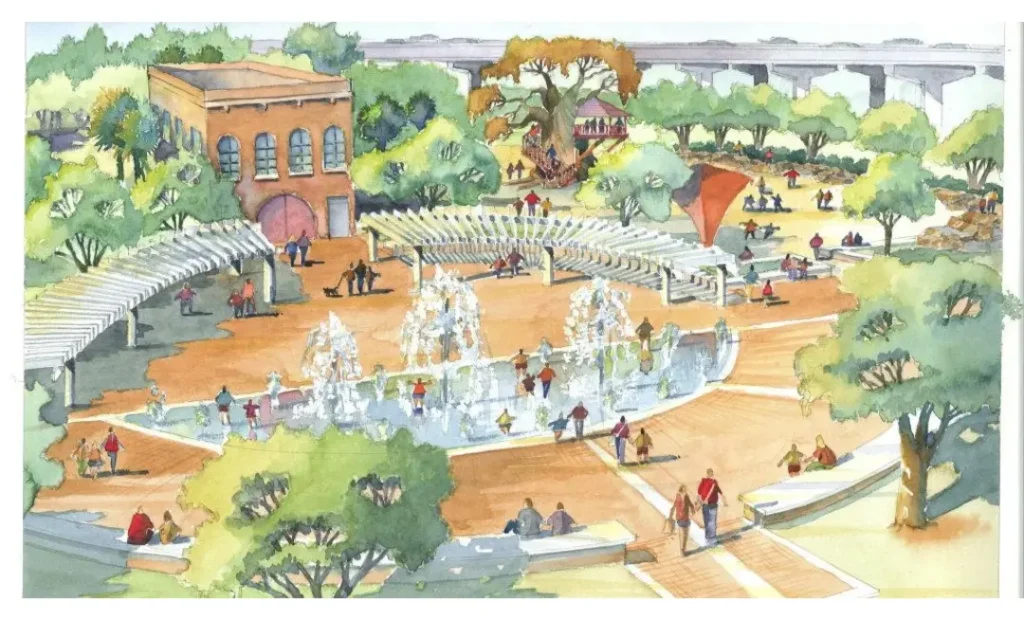

This is most critical in riverfronts where community members gather at the edge between the man-made city and nature, intersecting with ecological systems and infrastructure. Regenerating these spaces through inclusive placemaking will result in equity, belonging, and resilience.

This article explores how inclusive placemaking shapes riverfront regeneration, proven by real-life examples highlighting how spaces can be transformed with community participation.

Understanding Inclusive Placemaking

Inclusive placemaking is an essential strategy to achieve equity in urban development. It ensures that public spaces are curated with and for the whole community, including all groups that have been neglected historically. Inclusion can be embedded at any stage of a project; it is never too late to involve all the community in shaping their public spaces.

In the early stages, inclusive placemaking involves participatory mapping, co-visioning workshops, and reaching out to know exactly the needs of different groups. During the design phase, it is required to integrate universal accessibility, cultural relevance, and safety considerations. In the implementation phase, placemaking inclusion can be in offering local labor opportunities, and small vendor support. Even in the evaluation of the project the community represents the main contributor, providing feedback to assess their satisfaction and usefulness of the public space, and to guide future adjustments.

Core strategies of inclusive placemaking include equal participation, universal design, cultural integration, and shared stewardship. These principles together foster not only more accessible and representative spaces, but ones that are trusted, loved, and sustained by their communities.

Source: author

Why are riverfronts important?

Waterfronts have a significant importance, ecologically, socially, and economically. It provides a connection between urban spaces and the natural water, the man-made cities and natural elements, resulting in a scene that provokes tranquility and calmness.

Riverfronts work as inclusive public realms where people engage, socialize, and participate in cultural activities; it is often aided with walkways, seating, shared spaces, and other community gathering forms. In this context, it is common to find food trucks, craftsmen, and small-business traders activities, which benefits the local economy.

These features enhance the liveability of the place and further support the informal economy and encourage local entrepreneurship, especially among women, elders, and other marginalized groups. This way, riverfronts go beyond being just scenic assets, it becomes economic engines that benefit the wider parts of the community. Inclusion in riverfront planning also means creating space for those informal vendors who contribute significantly to the space’s identity and economy.

How can we achieve inclusion in Riverfront Regeneration?

Riverfront regeneration has been essential for attaining the full usage of this public space, socially, ecologically, and economically. However, to achieve serving residents equitably, we need to apply inclusivity in this regeneration process from the beginning.

Inclusion starts with an essential reflection: What exclusions have been made historically? What are the current problems restricting access, safety, and participation? These questions and further ones form the base of a people-centered approach, and can be inspected through surveys, interviews, and participatory mapping.

Then comes the evaluation for the current conditions of the riverfront, including accessibility, comfort, and functionality. As one study emphasizes:

“Accessibility must be incorporated from the design stage to sustain and increase usability by attracting more users to natural environments in urban areas.”

— Health Benefits of Riverfronts, 2019

When the gaps are identified, the redesign process can start -embedding inclusivity. This involves hosting community workshops inviting underrepresented groups to contribute meaningfully. Inclusive design necessitates reflecting the use of space, designating areas for informal vendors, and gatherings.

Finally, to sustain this inclusion in the course of time, shared stewardship is essential. Ongoing management should involve community-led meetings and regular feedback sessions that reinforce trust.

Case Study1: Cheonggyecheon River Revitalization, Seoul Inclusive Placemaking and Riverfront Renewal.

In Seoul, South Korea the Cheonggyecheon River Restoration Project is a prime example of what inclusive placemaking can do to transform a degraded urban riverfront into a vibrant public space. The Cheonggyecheon stream was covered by an overpass that led to great pollution, heat island effects and the loss of public access to the river.

Although the project was first suggested by Mayor Lee Myung-bak, what followed was a bottom up approach which saw in depth community engagement with local business owners affected by the project’s economic issues.

The place witnessed enhancing urban accessibility and walkability, reconnecting fragmented neighborhoods and opening new public pathways. Ecological restoration was central, improving air and water quality that improved public health. Also economically the project reduced traffic, brought in local investment, and social and cultural activities which in turn strengthened community cohesion.

There were a lot of challenges facing the project from the start, and during the regeneration, but Seoul was able to defeat them. Overall the Cheonggyecheon River Revitalization transformed a neglected urban space into a dynamic, inclusive and ecological public area which in turn set a global standard for riverfront regeneration.

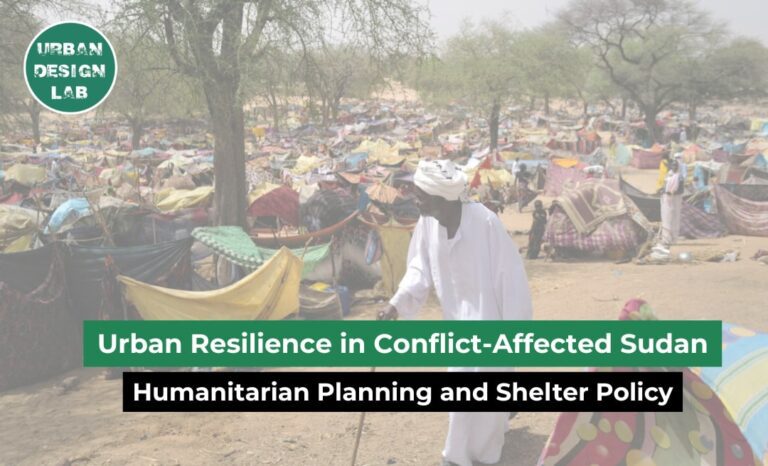

Case Study 3: Al Warrak, Egypt - Ongoing process

Al Warrak riverfront stretches 5 km along the Nile in Cairo, covering around 136 hectares. Originally farmland at the city’s edge, it has transformed into a densely populated urban zone, linked to the Ring Road but lacking basic services. The area faces several challenges—informal construction on green land, chaotic urban patterns, traffic congestion, and limited river access.

The site includes three main land types: informal housing on private farmland, government buildings (including a police station), and vacant plots. Despite its prime location, sustainable development is difficult due to tiny land parcels, scarce public spaces, and restricted connectivity to the waterfront.

Community consultations revealed two major concerns: residents in informal homes fear eviction, while landowners are frustrated by informal expansion, which they believe reduces their property value. Any regeneration effort must balance both perspectives to be successful.

A detailed land-use survey divided the area into nine sectors based on ownership, accessibility, and physical conditions. This helped reveal just how fragmented the site is. Moving forward, the key challenge is to create a development strategy that respects private ownership while ensuring existing residents have continued access to improved public spaces and essential services—bridging social, spatial, and economic divides.

Conclusion

Riverfronts are so much more than just pretty scenery. Think of them as the heart of a city, where the buzz of urban life dances with the calm of nature. They are where we gather, relax, and find our sense of belonging. But here’s the thing: when these special places get a makeover without the input of the folks who live right next door, we lose a crucial piece of the puzzle.

Inclusive placemaking is all about making sure everyone has a seat at the table. It is not just about drawing up plans for new paths or parks; it’s about genuinely asking, truly listening, and then creating spaces where everyone feels like they truly belong. Imagine local vendors setting up shop, families laughing at festivals, or young people finding a safe spot to hang out – these are the everyday moments that breathe life into our riverfronts.

Ultimately, inclusive placemaking isn’t just a fancy design term. It’s about mending and strengthening the bonds between people and the places they call home. And when we get it right, our riverfronts can transform into some of the most powerful, unifying spaces a city could ever hope for. They become truly ours.

References

- Cilliers, E. J., & Timmermans, W. (2014). The Importance of Creative Participatory Planning in the Public Place-Making Process. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 41(3), 413–429.

- Moreira, S. (2021, May 27). What Is Placemaking? ArchDaily.

- Attia, S., & Ibrahim, A. A. A. M. (2017). Accessible and Inclusive Public Space: The Regeneration of Waterfront in Informal Areas. Urban Research & Practice, 11(4), 314–337.

- Kang, M., & Kwon, Y. (2024). What Brings People to Riverfronts? Revealing Key Factors from Mobility Patterns Using De Facto Population Data. Land, 13(12), 2188–2188.

- Marrades, R., Collin, P., Catanzaro, M., & Mussi, E. (2021). Planning from Failure: Transforming a Waterfront through Experimentation in a Placemaking Living Lab. Urban Planning, 6(1), 221–234.

- Place-making, place-disruption, and place protection of urban blue spaces: perceptions of waterfront planning of a polluted urban waterbody

- Gupta, A., Yadav, M., & Nayak, B. K. (2025). A Systematic Literature Review on Inclusive Public Open Spaces: Accessibility Standards and Universal Design Principles. Urban Science, 9(6), 181.

- Jian, I. Y., Luo, J., & Chan, E. H. W. (2020). Spatial justice in public open space planning: Accessibility and inclusivity. Habitat International, 97, 102122.

Asma Alhassan

About the Author

Asma Alhassan is an architecture graduate from university of Khartoum, with a focus on urban design, research, and visual communication. Interested in exploring creative ways to enhance comfort and livability. She has contributed to studies on architectural and social issues, and participated in fieldwork and spatial analysis. With a background in editorial leadership, graphic design, and architectural modeling, Asma brings a multidisciplinary perspective to her work.

Related articles

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “

One Comment

Really enjoyed this article! It’s great to see how inclusive placemaking can make riverfront spaces more meaningful and connected to the communities around them.