Henri Lefebvre’s Right to the City: Shaping Everyday Urban Life

This article delves into Henri Lefebvre’s influential theory of the “Right to the City,” examining its relevance to contemporary urbanism and public space design. Lefebvre argued that urban life is shaped by more than just physical infrastructure. It reflects the lived experiences, rights, and aspirations of its inhabitants.

The post outlines how his theory challenges top-down planning approaches, advocating instead for participatory urban design that recognises the agency of everyday citizens. By investigating the concepts of social space, lived experience, and spatial justice, the article connects Lefebvre’s work to current debates in architecture and planning. It also explores real-world implications for designing inclusive, democratic urban environments and proposes ways to reinterpret city-making through collective rights and practices.

Understanding Lefebvre's Right to the City

Henri Lefebvre’s concept of the “Right to the City,” introduced in 1968, calls for more equitable access to urban life. He emphasised that the city is not merely a physical space but a social construct shaped by everyday practices.

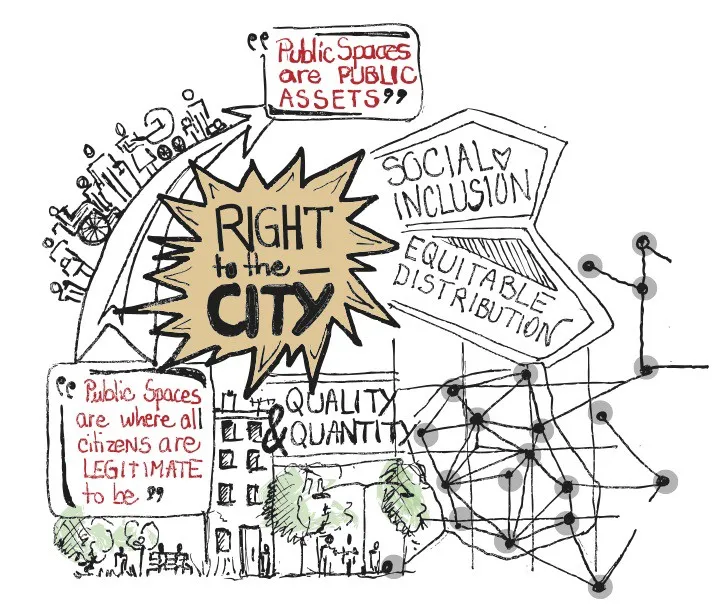

For Lefebvre, urban space is not neutral; it is constantly being produced and contested. This right extends beyond legal ownership, instead affirming the collective power of inhabitants to shape the city according to their needs.

Lefebvre argued for a shift from cities designed for capital accumulation to those fostering human flourishing, democratic participation, and diversity. His theory invites planners and architects to rethink cities as living, shared spaces where people actively contribute to the design and rhythm of everyday life.

Everyday Life and Spatial Practice

Lefebvre considered everyday life the heart of urban experience. He proposed a triad of spatial concepts: perceived space (daily routines), conceived space (planned design), and lived space (subjective experience). This framework helps to analyse how individuals inhabit, navigate, and reinterpret their environments. Everyday routines such as walking to work or gathering in public squares are crucial in shaping urban identity. Lefebvre’s theory urges architects and planners to acknowledge these lived rhythms and design spaces that accommodate them. This means creating places not just for efficiency, but also for interaction, spontaneity, and shared memory.

Such an approach bridges the gap between the planned and the lived, making urban design more inclusive and reflective of actual life.

Source: Website Link

Urban Justice and Inclusion

The “Right to the City” also foregrounds issues of social justice. Lefebvre challenged the exclusionary nature of modern urban development, which often displaces marginalised communities in favour of commercial interests. His theory provides a critical lens to examine gentrification, housing inequality, and the privatisation of public space. In advocating for spatial justice, Lefebvre argued that every urban inhabitant should have a voice in how their city is shaped.

Urban inclusion, therefore, is not a matter of charity but of democratic right. By focusing on access, participation, and visibility, architects and planners can resist homogenised urban forms and instead foster diverse, multicultural cities where all people feel a sense of belonging.

Implications for Architectural Practice

Lefebvre’s ideas have far-reaching implications for architecture and urban design.

They challenge professionals to move beyond formal aesthetics and instead consider the social production of space. This means involving communities in design processes, prioritising mixed-use developments, and preserving public spaces as democratic arenas. Architectural education can also benefit from incorporating Lefebvre’s theory, encouraging students to consider the human experience of space. Projects that empower local voices, adapt to diverse needs, and embrace uncertainty often lead to more resilient, meaningful places.

In practice, applying the “Right to the City” requires humility, empathy, and a willingness to engage in ongoing dialogue with those who inhabit the spaces we design.

Critiques and Contemporary Relevance

While Lefebvre’s theory has inspired progressive movements worldwide, it is not without critique.

Some scholars argue it is too abstract for practical implementation. Others note that claiming the “Right to the City” can be co-opted by political rhetoric without meaningful change. Despite this, the theory remains highly relevant in light of global urban challenges such as climate change, rising inequality, and mass urbanisation. Movements like Occupy, Black Lives Matter, and urban commons initiatives reflect Lefebvre’s spirit by asserting collective ownership of urban futures.

For contemporary designers and policymakers, the theory offers a critical framework to resist exclusion and advocate for more equitable, lived urban spaces.

Designing with a Democratic Ethos

Designing urban environments with Lefebvre’s democratic ethos means embedding participation, adaptability, and inclusivity into every stage of city-making. Architects, planners, and policy-makers must treat residents as co-creators, not just users. This could take the form of participatory workshops, tactical urbanism, or community-led design initiatives. It also involves resisting over-regulation and recognising informal practices that make cities vibrant and humane. Instead of imposing rigid masterplans, a democratic approach values open-ended spaces that evolve with their communities.

This mindset not only leads to more responsive design but also strengthens the civic bond between people and place, cultivating ownership and long-term stewardship of urban life.

-1

-1

-1

-1

Henri Lefebvre’s “Right to the City” continues to resonate as cities grapple with questions of equity, participation, and spatial justice. His theories remind us that the city is not a static entity but a dynamic space produced through collective experience. For architects and urbanists, the challenge is to translate these ideas into design practices that are democratic, inclusive, and grounded in everyday life. Embracing the lived realities of residents, recognising informal patterns of use, and fostering community ownership can transform urban spaces into places of empowerment.

Ultimately, realising the right to the city requires commitment not only from institutions but from all citizens who shape urban life.

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The Production of Space. Blackwell.

Lefebvre, H. (1996). Writings on Cities. Blackwell.

Harvey, D. (2008). The Right to the City. New Left Review, 53, 23-40.

Purcell, M. (2002). Excavating Lefebvre: The Right to the City and its Urban Politics of the Inhabitant. GeoJournal, 58(2), 99–108.

Mitchell, D. (2003). The Right to the City: Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space. Guilford Press.

Carmona, M. (2019). Principles for Public Space Design, Planning to Do Better. Urban Design International.

Massey, D. (2005). For Space. SAGE Publications.

Madanipour, A. (2003). Public and Private Spaces of the City. Routledge.

Holston, J. (2009). Insurgent Citizenship in an Era of Global Urban Peripheries. City & Society, 21(2), 245–67.

Soja, E. (2010). Seeking Spatial Justice. University of Minnesota Press.

Neha Lad

Neha Lad is an urban designer with a global outlook, shaped by her postgraduate journey at the Manchester School of Architecture and hands-on project work across continents. She thrives on connecting bold ideas with on-the-ground realities, weaving research and creativity into every design narrative. Whether sketching city plans or collaborating with diverse teams, Neha brings curiosity and energy to the table believing that great cities are built through both strategy and empathy. Passionate about inclusive urbanism, participatory planning, and ethical innovation, she is committed to shaping urban spaces that are resilient, human-centered, and ready for the challenges of tomorrow.

Related articles

Best Landscape Architecture Firms in Canada

Kim Dovey: Leading Theories on Informal Cities and Urban Assemblage

Top 10 QGIS Tools to Elevate Your Spatial Analysis Skills

Anne Hidalgo – aris Transformation & Pedestrian Policy

UDL GIS

Masterclass

Gis Made Easy- Learn to Map, Analyse and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

15th-19th December 2025

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “