Barcelona to Eliminate All Short-Term Rentals by 2029

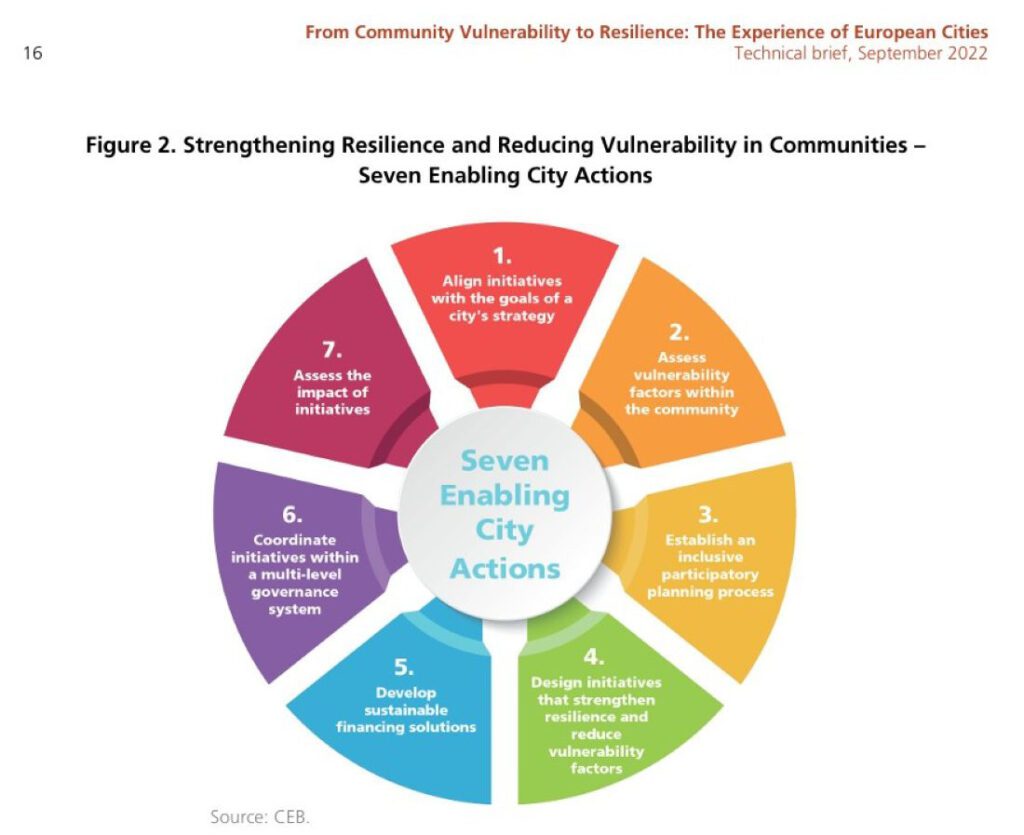

Barcelona’s decision to stop allowing short-term rentals (STRs) by 2029 is one of the most significant housing policies in Europe. The city plans to cancel about 10,000 tourist apartment licenses to return these apartments to the long-term market. This will ease pressures that have driven rents to record highs and forced residents to leave central neighborhoods. The initiative responds to growing dissatisfaction with the social and environmental problems caused by overtourism. It combines housing changes with strategies to be more sustainable and resilient.

The measure is based on a 2025 Constitutional Court ruling that said Barcelona has the legal right to make housing for residents a priority. The plan will roll out in phases, including financial audits, incentives to convert, and enforcement. The goal is to reduce economic disruption and build capacity for monitoring after the ban. Beyond affordability, the policy aims to protect the environment by reducing tourists and aligning with the city’s Climate Emergency goals. This article examines where the ban came from, how it was implemented, and what the expected results are. The findings suggest Barcelona’s approach could be a model for other cities balancing tourism with sustainable, resident-focused urban development.

From Tourist Economy to Resident-Centered Planning: Barcelona’s Paradigm Shift

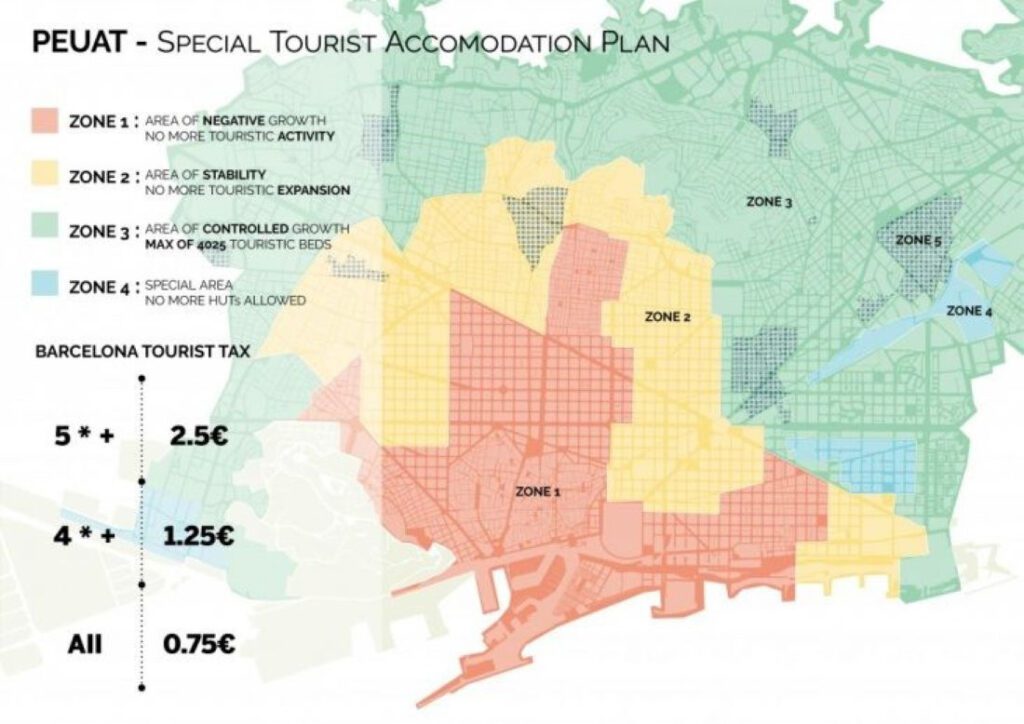

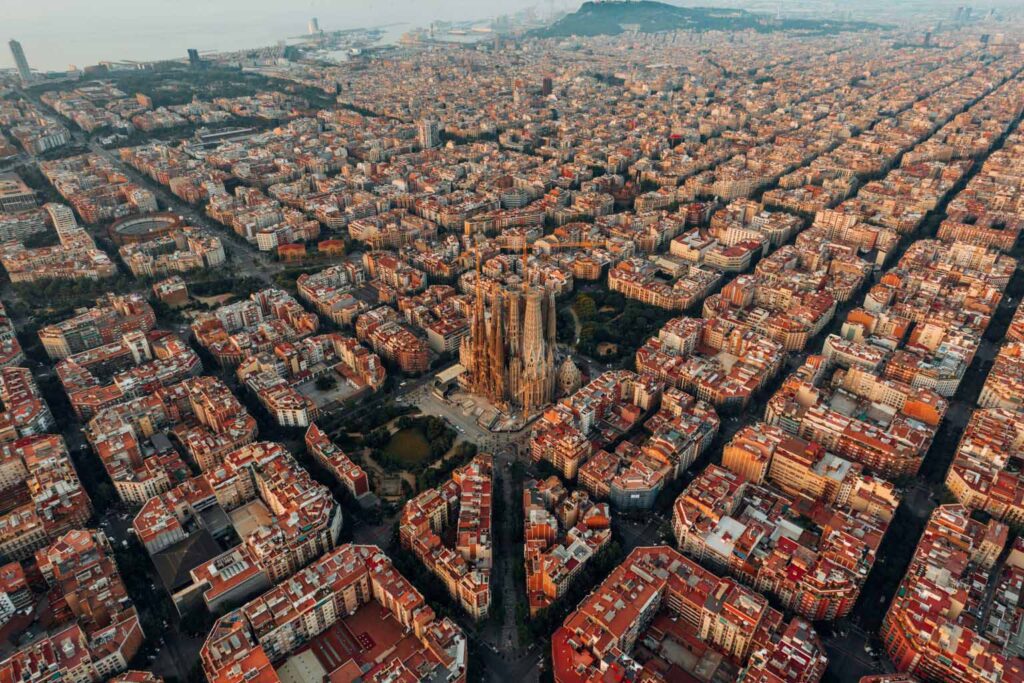

Barcelona has spent decades cultivating its global image as a cultural and architectural capital, attracting over 12 million visitors a year before the pandemic. But this has made it hard to find housing. Online platforms like Airbnb grew quickly after 2010, taking advantage of regulatory gaps. This led to more tourist accommodations in residential buildings, especially in historic neighborhoods like Ciutat Vella, El Born, and Eixample. The concentration of STRs removed thousands of homes from the long-term rental market and disrupted neighborhood life by replacing stable communities with transient populations.

The city’s 2024 decision to eliminate STRs shows a new focus. Instead of fitting in as many tourists as possible, Barcelona aims to create a housing system that supports community permanence. This change is part of a bigger trend in sustainable urbanism, where the social fabric is seen as vital infrastructure. The city plans to strengthen social ties, stabilize rents, and protect cultural heritage by returning STR units to the housing market. This is not just a housing policy but a major change in urban planning, shifting the city’s image toward its year-round residents.

Legal and Political Foundations: The Constitutional Court Ruling

In March 2025, Spain’s Constitutional Court ruled in favor of Barcelona’s authority to revoke all tourist rental licenses. This meant the city’s STR ban was legal. The court rejected property owners’ claims that the measure was an illegal seizure of property, citing the constitutional requirement under Article 47 to protect citizens’ right to housing. This decision not only confirmed the policy but also strengthened local governments’ ability to regulate housing markets for the public benefit.

The ruling made Mayor Jaume Collboni’s administration more confident. The administration had said that eliminating STRs was an important step in solving the city’s housing problems. Most people supported the ban, and surveys showed younger renters were especially in favor, as they faced higher rents than others. The ruling also had symbolic importance, showing that housing rights can take priority over private investment freedoms when public welfare is at risk. Importantly, the legal precedent extends beyond Barcelona. Other Spanish cities, including Valencia and Palma de Mallorca, have been watching closely and considering similar changes. This decision could change how housing is regulated in Spain, showing Barcelona as a leader in controlling its housing resources.

Source: Website Link

Phased Implementation and Urban Transition Strategy

The city is gradually banning short-term rentals (STRs) to avoid sudden problems for businesses while still reaching its 2029 goal. After the June 2024 announcement, no new STR licenses were issued. In 2025 and 2026, efforts will focus on auditing existing operators for tax and licensing compliance. Early enforcement has already recovered hundreds of thousands of euros, which can support housing programs.

By 2027, property owners who rent units long-term will receive incentives, with extra benefits for offering affordable housing. The city will also buy apartments in key locations for its social housing stock. In 2028, the final licensed STRs will expire, and in 2029 a special group will be created to stop illegal operations. This group will share information under new EU rules. The gradual timeline mirrors adaptive governance models, allowing policymakers to monitor the market and adjust as needed. It also gives landlords time to adapt business models, reducing resistance. Ultimately, the plan is about building capacity as well as enforcing policies, ensuring the post-STR era is both sustainable and enforceable.

Ecological Function and the Reduction of Tourism-Driven Environmental Stress

Tourism has a big impact on the environment, especially in historic cities. Visitor numbers rise sharply during certain months, increasing water, energy, and waste use. STRs worsen these pressures through frequent turnover, requiring more cleaning, laundry, and transport. A 2023 municipal sustainability report found that Barcelona neighborhoods with many STRs produced up to 25% more waste per person than those with mostly long-term residents.

By removing STRs, the city expects steadier resource demand, making infrastructure planning easier. Permanent residents have more consistent consumption patterns, making waste collection, water distribution, and energy provision more predictable and less resource-intensive. Fewer tourists also mean less wear on public spaces and transport networks, extending their lifespan and reducing maintenance costs. The policy aligns with Barcelona’s Climate Emergency Declaration, integrating housing reform into a broader plan for ecological resilience. By cutting tourism’s environmental footprint, the STR ban supports emissions reduction goals and adaptation measures for challenges such as drought. This demonstrates how housing policy can also protect the environment and how different areas of government can work together to create cities that are sustainable for both people and nature.

Housing Affordability and Social Equity as Core Sustainability Goals

The STR ban in Barcelona is meant to make housing more affordable. Rents have risen by more than 60% in some areas over the past decade, outpacing wage growth and making it hard for low- and middle-income people to find housing. The increase in STRs has been a major factor, converting homes into tourist rentals and reducing those available for locals.

Returning 10,000 units to the long-term market could help. If Barcelona can reduce rent prices as Lisbon did after similar restrictions where prices dropped by up to 14% in certain areas, it will significantly improve affordability. Greater affordability also supports a more equitable society, ensuring diverse populations can remain in central neighborhoods rather than moving to the suburbs. There is a well-documented link between housing stability and sustainability. Stable residents invest more in their communities, participate in local governance, and support local businesses. By reusing these homes, Barcelona can strengthen its social infrastructure, which is as important to a city as its physical infrastructure. The policy works to ensure everyone has a safe place to live while protecting the environment.

Architectural and Urban Form Implications: Adaptive Reuse of Housing Stock

When STR units are reabsorbed into the residential market, it affects the design and layout of the city. Many tourist apartments have been renovated to appeal to short-stay guests, with modern kitchens, open layouts, and energy-efficient lighting. These upgrades, while designed for a temporary audience, can improve long-term housing quality when used by residents.

Barcelona has a chance to ensure sustainability requirements are part of reintegration. Property owners might be motivated to make environmentally friendly improvements, such as better insulation, solar panels, or rainwater collection systems. This could align housing policy with EU Green Deal targets, reducing pollution from city operations and supporting the goal of becoming climate-neutral by 2050. From an urban planning perspective, changes in residency patterns can make neighborhoods more stable and predictable in public space use. This helps improve urban design by ensuring housing, roads, and other infrastructure match residents’ needs. Using STR units in this way benefits both the environment and society, helping the city become more sustainable and livable.

Resilience Through Community Stability and Local Economies

Strong communities that work together are key to making a city resilient. Too many visitors and not enough permanent residents weaken community connections and reduce civic engagement. People who have lived in a place for a long time are more likely to help out in their community and join mutual aid groups, which is especially important in emergencies.

By bringing people back to live in the city, Barcelona is strengthening its social infrastructure. When populations are stable, it’s easier for businesses to plan and invest. The retail and service sectors can shift from depending on tourists to focusing on residents. Research from Amsterdam and Edinburgh suggests these changes help local businesses survive and enhance community-led urban improvements. With fewer tourists, tensions between visitors and locals ease, fostering harmony. This harmony is essential for resilience whether facing climate challenges, economic downturns, or public health crises. Trust and cooperation among residents are vital in overcoming such problems. In this sense, the STR ban is both a resilience policy and a housing measure.

Comparative European Context and Policy Innovation

While STR regulation is not unique to Barcelona, the scope of its ban sets it apart. Paris has strict registration requirements and limits the number of days a year short-term rentals (STRs) can operate. Amsterdam limits STRs to certain neighborhoods, and Lisbon has temporarily halted new STRs in areas with high saturation. But no other major European city has promised to eliminate STRs completely.

Barcelona is taking a bold step forward, aided by new EU rules on STR data sharing that will take effect in 2026. These rules will require platforms to provide detailed operational data to local authorities, improving enforcement and discouraging illegal rentals. This combination of local measures with broader European rules increases the likelihood of success. The city’s model could inspire similar projects elsewhere, especially in tourism-heavy areas facing housing shortages. However, successful replication will depend on legal frameworks, political will, and public support. Barcelona has aligned these factors effectively. Its mix of strong legal precedent, phased implementation, and integration with sustainability goals makes it a leading example of innovative housing governance.

Risks, Challenges, and Metrics for Policy Evaluation

No policy is without challenges, and Barcelona’s STR ban faces several. The hospitality sector might see a decrease in the number of visitor beds, which could affect jobs and income related to tourism. If the government doesn’t have enough resources to enforce the rules, people might keep doing illegal STR activities. This could also cause tourists to travel to other places, which could affect the tourism industry in nearby towns.

The city has set key metrics to measure success. These include changes in median rent, the number of units converted to long-term use, neighborhood population stability, and environmental indicators such as per capita water consumption. Regular public reporting will be essential for maintaining transparency and trust. Integrating housing, sustainability, and resilience goals means success will have many aspects. A small decrease in rent, along with a big improvement in the environment, could still be a good outcome overall. But if they don’t enforce the ban effectively, it could undo the good things they’ve done for society and the environment. The policy will last as long as politicians are committed to it, it has enough money, and the ways it is enforced can adapt to changing market conditions.

Conclusion

Barcelona’s decision to get rid of all short-term rentals by 2029 is an important step in managing the city. It combines housing justice, environmental sustainability, and community resilience into one plan. The plan is supported by the law and many people. It tries to make housing markets stable, reduce ecological problems caused by tourism, and make neighborhoods more united. The change will be hard because of money problems and enforcing the rules, but it will also have a lot of good effects. Other cities around the world will be able to use this change as an example when they have similar problems between tourism and what the people who live there need. We won’t know the full impact of this change for a few years, but Barcelona’s integrated approach is an example of how urban policy can combine social equity (making sure everyone has what they need) with ecological function (making sure the city is sustainable). This approach creates a more sustainable and livable city for future generations.

References

- Ajuntament de Barcelona. (2024). Housing Observatory report. https://habitatge.barcelona/en

- Blanco, I., & Subirats, J. (2023). Urban governance and the politics of housing. UAB Press.

- European Commission. (2022, November 7). Short-term rental regulation: EU framework for data sharing. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_6493

- Gutiérrez, J., García-Palomares, J. C., Romanillos, G., & Salas-Olmedo, M. H. (2021). Short-term rentals and housing prices in Barcelona: Causation or correlation? Journal of Urban Economics, 124, 103347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2021.103347

- Hürriyet Daily News. (2024, June 23). Barcelona aims to become Airbnb‑free zone by 2029. Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved from https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/barcelona-aims-to-become-airbnb-free-zone-by-2029-197712

- The Guardian. (2024, June 22). Barcelona to ban apartment rentals to tourists in bid to cut housing costs. https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/jun/22/barcelona-to-ban-apartment-rentals-to-tourists-in-bid-to-cut-housing-costs

Seakmy Ty

About the author

Seakmy Ty is a Cambodian architecture student pursuing a master’s degree in urban planning in France. Originally from Phnom Penh, a city that is rapidly changing due to urban growth, she has developed a deep passion for sustainable urban design and planning. She has received academic training in smart city systems, energy efficiency, and resilience strategies. Seakmy is particularly interested in how design and governance can create cities that balance rapid development with long-term environmental and social well-being.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “

4 Comments