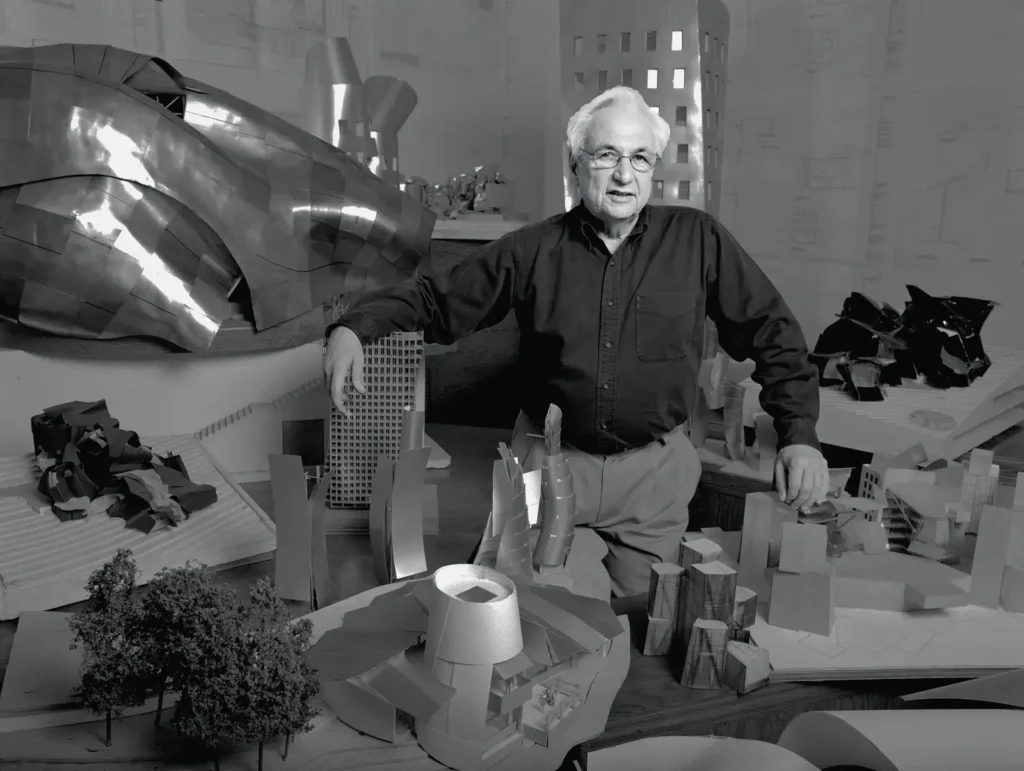

Frank Gehry’s ascent from unconventional Los Angeles experimenter to global architectural figure crystallised with the opening of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao in 1997. The building, with its sweeping titanium panels and dynamic, almost liquid form, expanded the possibilities of architectural expression and demonstrated how a single structure could catalyse cultural and economic transformation. Bilbao became more than a museum; it became a symbol of urban reinvention, giving rise to what would later be called the “Bilbao effect”, the notion that visionary architecture could reshape a city’s identity and trajectory.

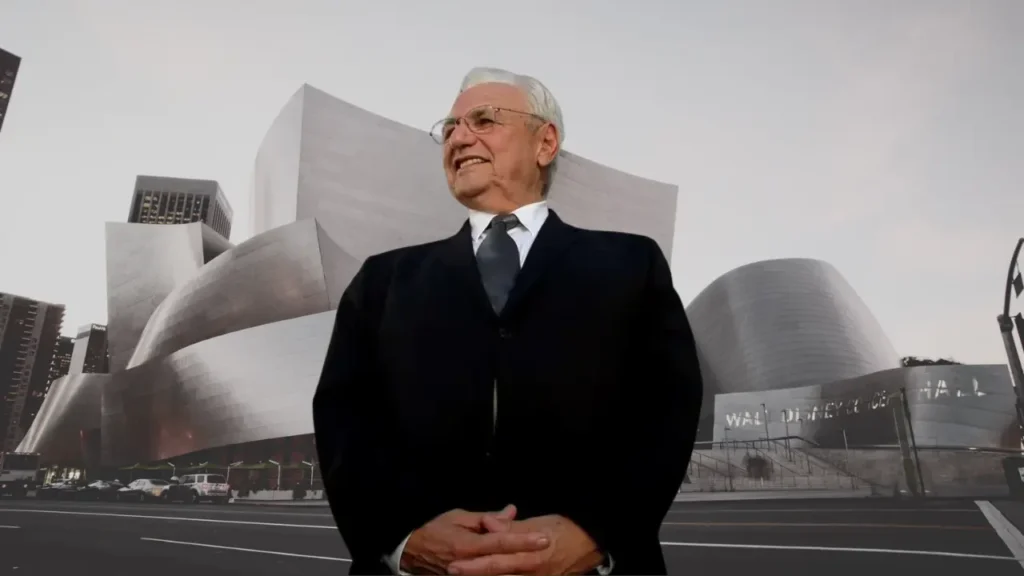

The Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, completed in 2003, further solidified Gehry’s stature. Its stainless-steel sails curve outward like a frozen explosion of movement, capturing both the energy of the city and the precision of world-class acoustics inside. It showed that Gehry’s bold forms were not superficial gestures but deeply considered responses to performance, experience, and civic presence. With these works he bridged the distance between sculpture and architecture, creating spaces that were as much cultural icons as functional buildings. Across continents, Gehry’s projects challenged engineers, delighted audiences, and redefined what cities could aspire to. His architecture became a form of public theatre, reshaping skylines while provoking debate about spectacle, innovation, and the role of the architect in shaping collective memory.

One Comment

Your writing always inspires me to learn more.