Book Review: Dream Cities by Wade Graham

Wade Graham’s Dream Cities: Seven Urban Ideas That Shape the World is a vibrant exploration of the architectural ideologies that have significantly influenced urban landscapes over the past century. In the book, Graham unpacks seven pivotal ideas that have shaped cities into the spaces we navigate today—whether in the form of suburban sprawl, eco-friendly high-rises, or sprawling shopping malls. The author’s work is a hybrid of cultural history and architectural critique, ideal for both professionals and architecture enthusiasts aiming to understand how these spaces emerged, evolved, and often, fell short of their original utopian visions.

The book divides into chapters that each spotlight a different urban archetype. Through these, Graham explores influential figures like Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Jane Jacobs, each representing a unique ideological movement. For instance, Le Corbusier’s “Radiant City” model introduced the concept of tower blocks surrounded by open green space, which, while influential, has been criticized for fostering isolation in modern cities rather than community vitality. Wright’s Broadacre City emphasized suburban independence, reflecting America’s mid-century aspirations yet sparking contemporary debates on sprawl and its environmental impact. Graham also draws a sharp contrast with the more human-centric approach advocated by Jane Jacobs, whose emphasis on organic, street-level interactions laid the groundwork for today’s New Urbanism.

Castles

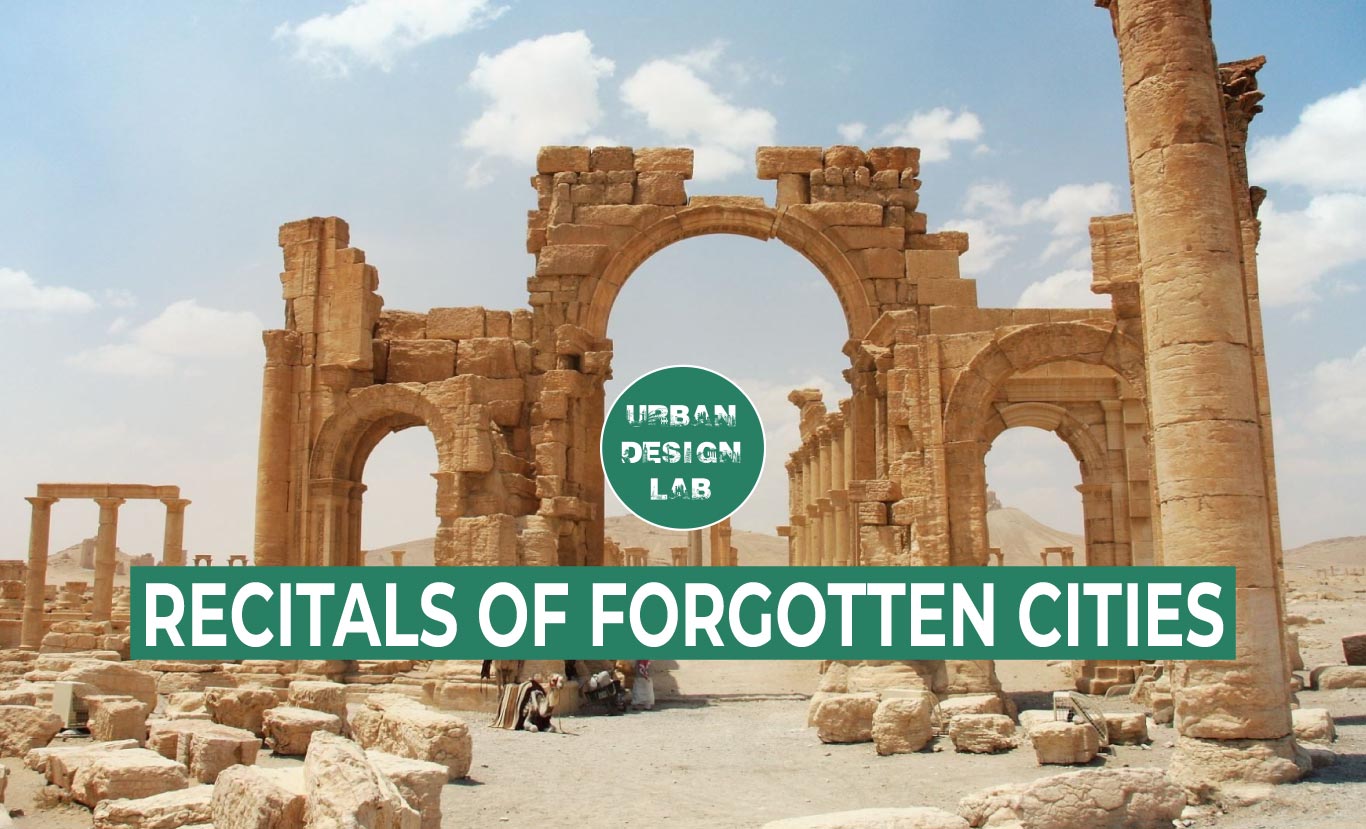

In Dream Cities, Wade Graham’s chapter on “The Romantic City” delves into the works and influence of Bertram Goodhue, an architect who brought a unique vision to early 20th-century American architecture through his interpretations of Spanish and Gothic revival styles. Goodhue’s Romantic City concept manifests in white stucco facades, barred windows, and iconic red-tiled roofs, creating a sense of cohesive, visually rich urban spaces that evoke the charm and spirituality of old Spanish towns. This architectural vision is best exemplified in Goodhue’s design competitions for iconic religious structures, such as the Saint John the Divine Cathedral in New York and his winning design for Saint Matthew Cathedral in Dallas.

Goodhue’s fascination with the Gothic revival was part of a broader architectural movement that aimed to romanticize and recontextualize European architectural motifs within American landscapes. Gothic revival architects emphasized elaborate ornamentation, often using pointed arches, tracery, and intricate stonework to create an evocative, almost mythic atmosphere that contrasted with the industrial aesthetic popular at the time. Churches, villas, and castles in this style sought to infuse spaces with historical grandeur and a sense of continuity, aiming to evoke an emotional connection to the past. This Gothic aesthetic became a defining feature of urban landscapes in various American cities, shaping public spaces and private estates alike with an ethos of timeless beauty and romantic allure

Monuments

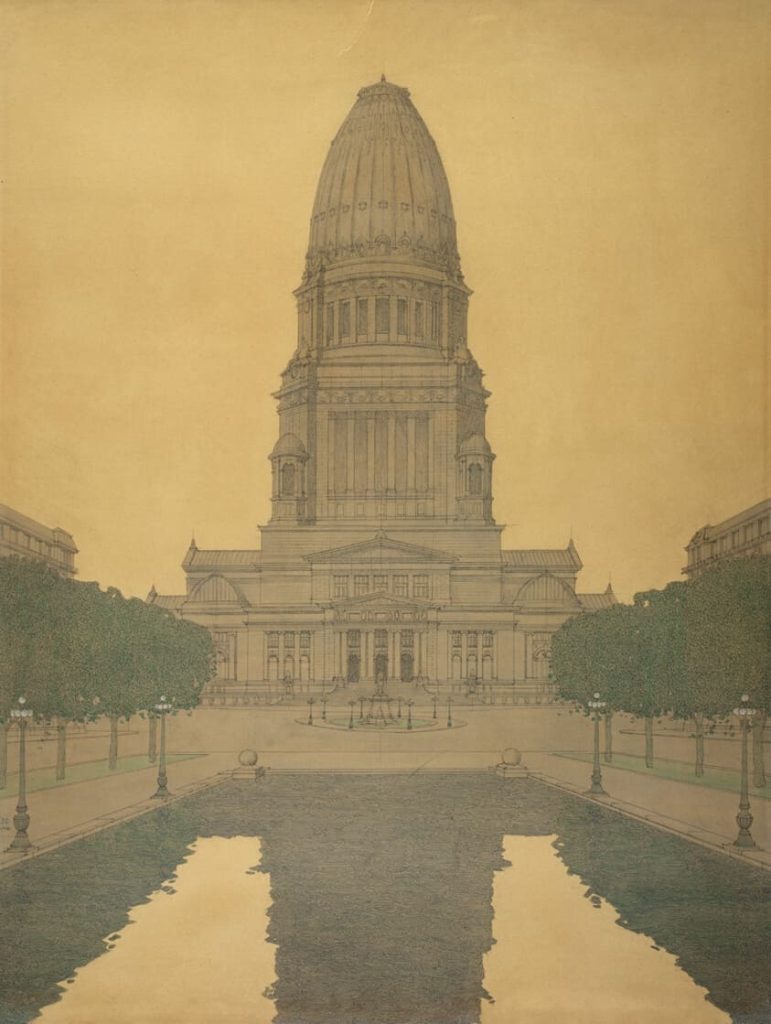

In Dream Cities, the chapter on “The Ordered City” explores Daniel Burnham’s pioneering contributions to urban planning and skyscraper design, framing his work as foundational to the architectural identity of Chicago and beyond. Known as the “father of skyscrapers,” Burnham’s architectural style blended functionality with grandeur, exemplified by landmark buildings like the ten-story Montauk Building and the 16-story Monadnock Building. These structures established a new era of high-rise commercial architecture, symbolizing the economic power and vertical growth of American cities at the turn of the century.

Burnham’s urban vision extended beyond individual buildings, impacting the cityscape of Chicago, San Francisco, and even Manila. His “City Beautiful” movement focused on creating monumental neoclassical structures, marked by symmetrical layouts, grand façades, and white marble columns. This approach emphasized order, balance, and civic pride, featuring axial designs in plazas and boulevards surrounded by greenery, punctuated with bronze or marble statues celebrating historic figures

Source: Website Link

Slabs

In Dream Cities, the chapter on “The Rational City” highlights the radical urban visions of Le Corbusier and Robert Moses, who championed a utilitarian architectural style centered on slab structures—modernist towers of glass and concrete that emphasized simplicity and efficiency. Characterized by flat, grid-like façades and separated from the surrounding urban fabric, these buildings were typically set apart from pedestrian pathways, creating spaces that some argue felt disconnected and impersonal. This “slab” style, inspired by Le Corbusier’s visions of “Radiant Cities,” gained traction in mid-century America and became a symbol of modernity, especially in office buildings and institutional spaces across cities like New York and Chicago.

Le Corbusier envisioned cities where tall, minimalist buildings with repeating façades and large glass or concrete walls would be organized into orderly zones, surrounded by green spaces. Robert Moses applied similar principles in his urban renewal projects, prioritizing car accessibility and creating wide, car-centric avenues that diminished walkability. The “slab” design often emphasized functionality over interaction, reinforcing separation between people and the built environment and leading to a style many found cold and uninviting. This design philosophy influenced major American cities, with notable examples including public housing projects that adopted the slab model, often surrounded by expansive, unused open space

Homesteads

In Dream Cities, the chapter on “The Anticity” spotlights Frank Lloyd Wright’s visionary concept of Broadacre City, a radical alternative to the urban landscapes of his time. Conceived during the Great Depression—a period marked by economic hardship and widespread criticism of capitalism—Broadacre City proposed a decentralized, egalitarian model that defied traditional urban planning. Wright’s vision was to replace dense, hierarchical cities with a sprawling, agrarian landscape where each family would own a small plot of land, effectively blending urban and rural life. This model, famously illustrated by a cardboard mockup constructed by his apprentices at the Taliesin Fellowship, was more reminiscent of a dispersed town network than a conventional city.

Broadacre City was not merely an extension of rural ideals but a complete rejection of centralized urbanism. Wright’s plan emphasized individual autonomy, self-sufficiency, and the dissolution of the boundary between urban and rural spaces, which he saw as key to reducing social inequality. The concept favored decentralization, advocating for small, local centers within a vast landscape that allowed inhabitants to engage in agriculture while still having access to community resources. With no architectural center and a focus on sustainable living, Broadacre City aimed to foster harmony between people and the land.

Corals

In Dream Cities, the chapter on “The Self-Organizing City” examines the ideas of Jane Jacobs and Andres Duany, two influential figures whose work challenged top-down urban renewal projects like those championed by Robert Moses. Jacobs, a strong advocate for organic, community-focused urbanism, famously opposed large-scale redevelopment efforts that she believed would destroy the social fabric of neighborhoods. Her activism helped shape the direction of New Urbanism, a movement that Duany and others later expanded upon. In cities like New York and across the tri-state area, these efforts aimed to preserve communities affected by modernization projects, such as highway and tunnel construction, which had displaced housing and green spaces for infrastructure.

Jacobs’ and Duany’s vision of urbanism emphasizes human-scale design and the importance of self-organization in cities. This New Urbanist approach is characterized by mixed-use zoning, limited building heights, and varied architectural styles that reflect local history and aesthetics. Their advocacy led to design principles that prioritize pedestrian-friendly streets, thoughtful landscaping, and diverse architectural codes that ensure variation in style, color, and materials. Street furniture, trees, and landscaping are integrated into public spaces, promoting both utility and aesthetic appeal.

Malls

In Dream Cities, the chapter on “Shopping World” explores the transformative impact of architects Victor Gruen and Jon Jerde on the American retail landscape. Gruen, often regarded as the “father of the shopping mall,” introduced the concept of the enclosed mall as a hub of social and economic activity. His design philosophy went beyond mere shopping, seeking to replicate a community center where people could gather, interact, and, of course, shop. Gruen’s malls aimed to mimic the vitality of urban streets within a controlled, pedestrian-friendly environment, integrating walkways, communal spaces, and storefronts under a single roof, effectively creating a new kind of urban ecosystem.

Jon Jerde later expanded on Gruen’s ideas, creating immersive “shopping worlds” that prioritized atmosphere and experience. Jerde’s designs, such as San Diego’s Horton Plaza, used vibrant architecture, varied levels, and colorful facades to create retail environments that felt like theme parks. These spaces encouraged not just shopping but exploration and engagement, transforming malls into social destinations and entertainment centers. Jerde’s work emphasized a concept called “verisimilitude,” where the mall environment felt authentic and immersive, almost like a mini-city. This style can be seen in sprawling shopping centers worldwide, where pedestrian paths wind around a mix of retail, restaurants, and entertainment venues, blending elements of city and suburbia

Habitats

In Dream Cities, the final chapter, “Habitats and Techno-Ecologies,” explores the visionary urban concepts of Kenzo Tange and Norman Foster, two architects who harnessed technology to address ecological and urban challenges. In the 1960s, Tange and his contemporaries envisioned cities as flexible, regenerative habitats that adapted to changing environmental and social needs. This era marked the height of technological optimism, reflected in experimental designs such as transparent geodesic domes and modular, expandable structures aimed at regulating urban climates and reducing pollution. Tange’s work often emphasized “Metabolism,” a concept that promoted adaptable, capsule-like urban forms that could evolve organically, suggesting a living, interconnected city.

Norman Foster advanced this idea of tech-forward urbanism with sustainable architecture that incorporates environmental controls for water, waste, and energy efficiency. His designs, such as London’s “Gherkin,” exemplify futuristic architecture integrated with eco-friendly systems, including natural ventilation and efficient energy use. Foster and others like Buckminster Fuller envisioned domes and “floating” structures as solutions for dense urban centers, blending innovative engineering with environmental foresight. These designs aimed to foster sustainable cities through high-tech, modular, and flexible habitats that adapt to environmental conditions, promoting a balance between modern urban life and ecological sustainability

Conclusion

Dream Cities by Wade Graham is a compelling exploration of influential architects whose unique visions shaped the evolution of architectural and urban design. By interweaving the biographies and philosophies of icons like Bertram Goodhue, Daniel Burnham, Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright, Jane Jacobs, and others, Graham presents a rich narrative of how diverse movements in architecture—ranging from romanticism to modernism and ecological urbanism—were molded by social, political, economic, and technological forces. Each chapter delves into a specific “city type,” such as the Romantic City, the Ordered City, and the Techno-Ecological City, framing these styles as responses to the needs and challenges of their times.

References

- Ellis, C. (2002). The new urbanism: Critiques and rebuttals. Journal of Urban Design, 7(3), 261-291. https://doi.org/10.1080/1357480022000039330

- Antonova, N., Grunt, E., & Merenkov, A. (2017). Monuments in the structure of an urban environment: The source of social memory and the marker of the urban space. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 245, 062029. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899x/245/6/062029

- Von Simson, O. G. (1952). The gothic cathedral: Design and meaning. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 11(3), 6-16. https://doi.org/10.2307/987608

- Duggett, T. (2015). 18 gothic forms of time: Architecture, Romanticism, medievalism. Romantic Gothic, 339-360. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780748696758-018

- Chapin, T. (2002). Beyond the entrepreneurial city: Municipal capitalism in San Diego. Journal of Urban Affairs, 24(5), 565-581. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9906.00144

- Gillette, H. (1985). The evolution of the planned shopping center in suburb and city. Journal of the American Planning Association, 51(4), 449-460. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944368508976833

Enrico Vincensius Yudistira Harryanto

About the Author

Enrico Vincensius Yudistira Harryanto is Bachelor of Urban and Regional Planning from Kalimantan Institute of Technology , Balikpapan (Indonesia). He major and area of expertise and interest research and project in Urban Design and Architecture, Urban Landscape, Urban Conservation such as cultural heritage conservation, Smart City, Geographic Information System analysis and modelling. Enrico also have expertise in Graphic Design, Illustration, Photography adn Videography to support attractive data visualization, analysis and publication.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

Best Landscape Architecture Firms in Canada

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “