Designing the Last Mile Delivery Lane to Save Urban Streets

E-commerce is growing quickly, which has made the “last-mile” delivery problem worse. This problem creates daily conflicts on city streets. Vans double-park in bus lanes, cargo bikes are squeezed out by trucks, and pedestrians can’t use sidewalks because they’re blocked, all of which show that the urban delivery ecosystem is poorly designed. This article says that the future of strong, sustainable cities depends on changing the design of the road as a key part of public space.

The discussion is based on examples from around the world. It looks at how the design of delivery lanes affects traffic, the environment, and how livable a neighborhood is. It looks at ways to manage curbs, create protected loading areas, build infrastructure for cargo bikes, and set up micro-distribution hubs. It also looks at how these affect carbon emissions, pedestrian safety, and equity. The article combines research on urban design, policy frameworks, and real-world interventions. It also talks about last-mile logistics. It talks about these things in the context of sustainable mobility and ecological resilience. By comparing new ways cities like Paris, Barcelona, Seattle, and Singapore manage their growing number of deliveries, it shows both the good and bad parts of this approach.

The Scale of the Last-Mile Delivery Problem

Last-mile delivery is the most resource-intensive stage of logistics. It’s when goods are moved from distribution hubs to their final destination. It accounts for just a small part of supply chain distance, but it generates almost 53% of total shipping costs and a disproportionate share of urban traffic congestion. The growth of online shopping has made this problem worse. Studies from the World Economic Forum say that demand for city deliveries will increase by 36% by 2030 if we do not take action (World Economic Forum, 2020).

These problems are easy to see every day. Trucks are blocking bus lanes, delivery trucks are spilling onto sidewalks, and cyclists are forced into traffic because of parked vans. These dynamics make traffic worse and also make the air in the city more polluted by increasing emissions, noise, and air pollutants at ground level. This has led to problems with how streets are designed. Streets are designed for cars and people walking, but now they are also used by delivery trucks. If we don’t take action, cities will face increasing risks, including unsafe streets, noncompliance with climate regulations, and reduced resilience in their transportation systems.

Streets as Ecological and Social Systems

Streets are more than just ways to get around. They are also important for the environment and for people. Streets help make cities work. They control the local weather by covering the ground with trees and other plants, and by keeping the ground open. They also help people meet each other and provide equal access to transportation. But the unchecked growth of delivery vehicles undermines these functions.

When sidewalks are used as staging zones for construction, the ecological roles of streets are compromised. Streets are important for absorbing stormwater, providing corridors for biodiversity, and making it comfortable for pedestrians. Noise and exhaust emissions harm public health, and the space needed for trees, rain gardens, or bike lanes is taken up by curbside spaces. This viewpoint sees the problems at the last mile not just as a practical issue but as a crisis in how things are designed. To do this, delivery lanes must be designed to be environmentally friendly. This helps make sure that last-mile logistics fit with broader plans to adapt to the climate in cities.

Source: Website Link

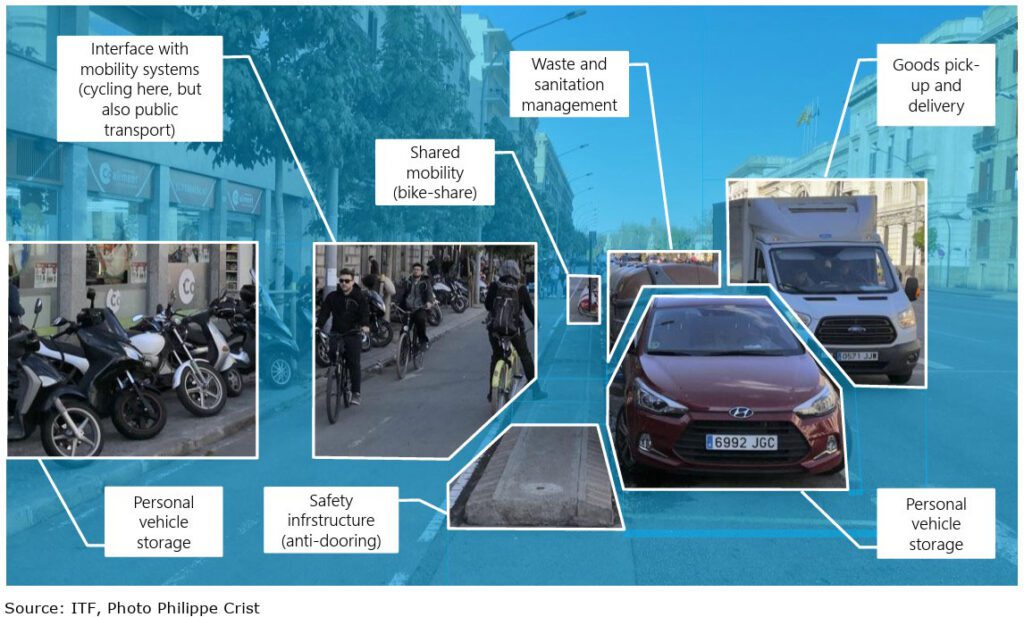

Anatomy of the Delivery Lane: From Ad Hoc to Designed Infrastructure

The “delivery lane” is usually not set in stone. In many cities, it is simply wherever a truck can stop. This could be bus lanes, intersections, bike lanes, or even crosswalks. This temporary approach shows that cities have not yet reimagined curb space as an important urban asset. Designing delivery lanes requires specificity:

- Spatial design: the design of the space includes special areas for loading and unloading that are wide enough for cargo bikes and vans. These areas have protective barriers to keep cyclists and pedestrians safe.

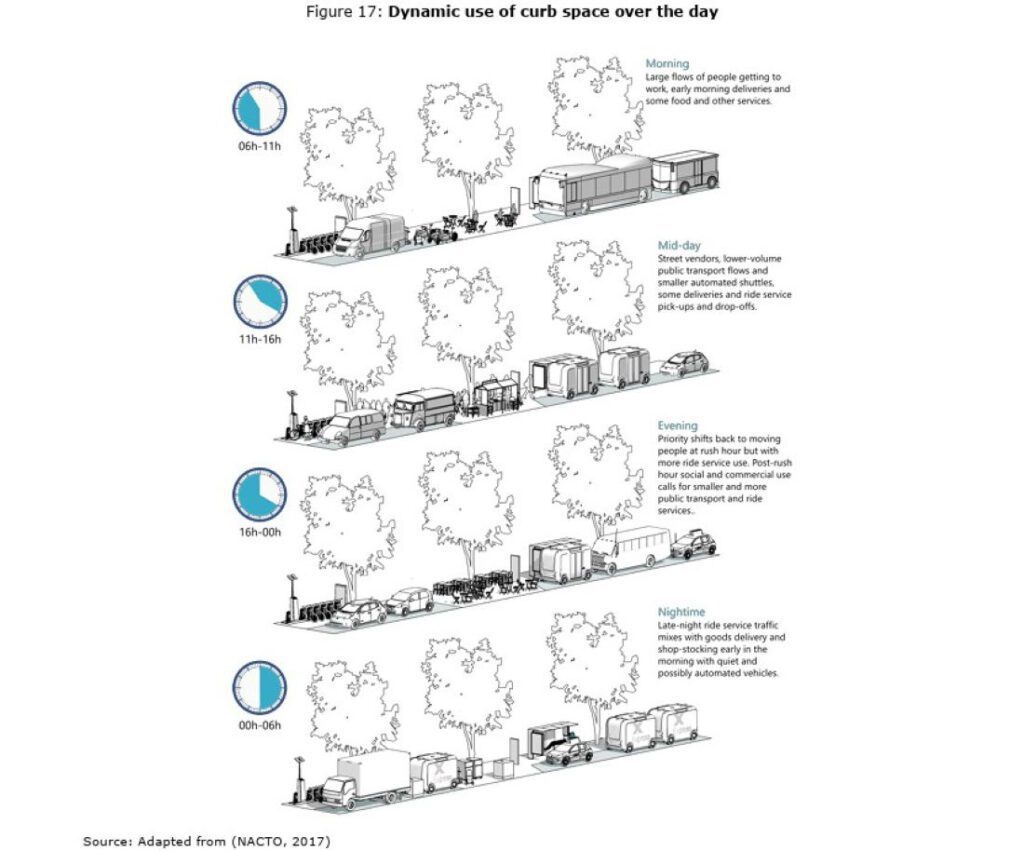

- Temporal design: time-based restrictions that make deliveries more efficient by timing them to occur during less busy times.

- Digital design: integration with curb management software that allocates slots dynamically.

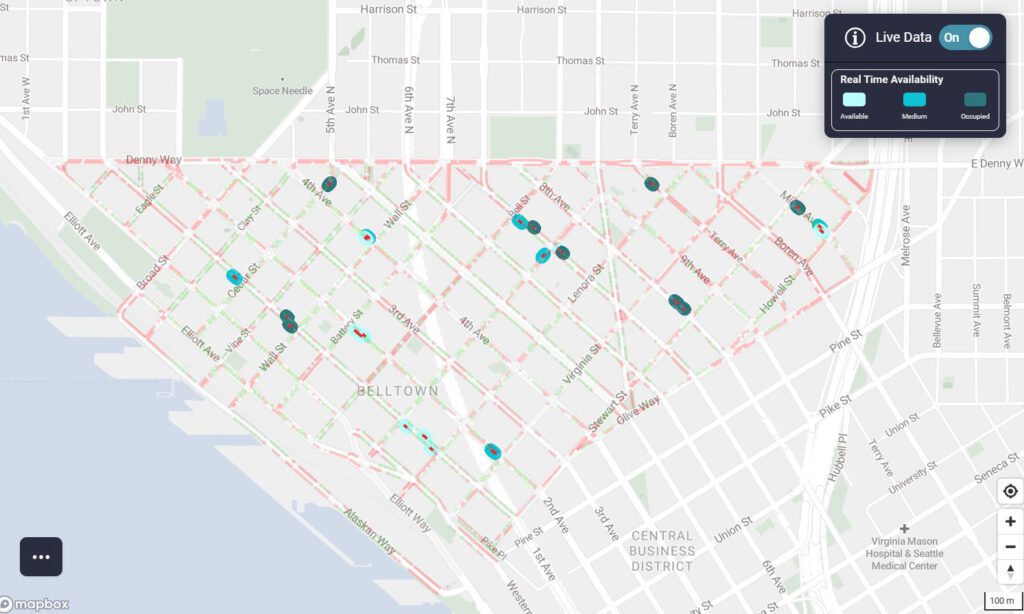

For example, Seattle’s Urban Freight Lab has created digital maps of loading zones and booking systems that allow truck drivers to reserve space in real time (Urban Freight Lab, University of Washington). These will reduce illegal parking and make it safer for everyone. By switching from making things up as we go to having a plan, delivery routes can become spaces that serve many purposes. These spaces can balance getting goods from one place to another efficiently with protecting the environment and improving society.

Microhubs and Cargo Bikes: A New Logistics Ecosystem

One of the best ways to make sure that packages reach their destination in an eco-friendly way is to use small distribution centers and cargo bikes. Microhubs are small facilities often located in neighborhoods. They are used to transfer goods from large trucks to smaller, zero-emission vehicles.

Paris has been pushing hard for this model. It has been helping logistics companies use electric cargo bikes for last-mile delivery. By 2026, the city plans to make all deliveries within its main area completely zero-emission. This reduces traffic and cuts pollution. It also frees up space on city streets that was previously taken up by vans. Cargo bikes also help improve the environment. They are quieter, don’t take up much space, and work well with bike lanes. Studies show that cargo bikes can replace up to 25% of van trips in busy cities, while also improving delivery speed in busy areas. Microhubs and cargo bikes work together to create a strong system that is good for people and the environment. They help to spread out the work of moving things around while reducing the harm to the environment.

Dynamic Curb Management: The Smart Street Approach

Static delivery bays often aren’t enough for changing demand. Dynamic curb management uses digital platforms, sensors, and real-time data to adjust how curb space is used. Barcelona’s “superblocks” program, which is most famous for creating more space for pedestrians, has also tested a smart curb management system. Vehicles reserve their delivery slots online, which helps avoid parking illegally and conflicts with cyclists. Los Angeles has also tried digital loading zones, where carriers pay different rates based on demand. This approach recognizes the curb as a changing surface rather than a fixed area. If cities price curb use well, they can make sure deliveries are efficient and fund improvements to their infrastructure. Importantly, dynamic curb management makes the system stronger. It adapts to sudden increases in demand without needing to make permanent changes to the streets. This makes sure that there is enough space for traffic and for the environment.

Global Case Studies: Successes and Failures in Delivery Lane Design

When we look at different situations, we can learn a lot. But we can also learn some important lessons.

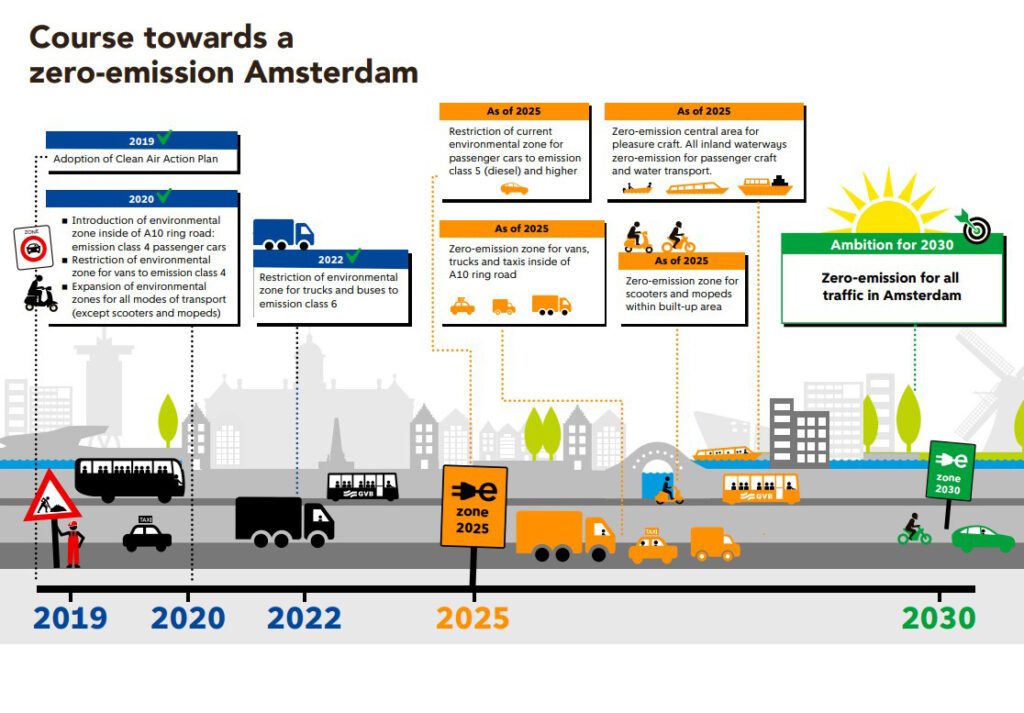

- Amsterdam: The city has banned diesel vans from its center by 2025, and is instead supporting a network of cargo bikes. Success depends on having good bike lanes and a government that is serious about reducing greenhouse gases.

- Singapore: Despite its reputation as a smart city, the delivery lanes are underdeveloped, and trucks often block major roads. This shows that technology alone is not enough.

- New York City: “Off-hour delivery” programs encourage nighttime deliveries, which reduces daytime traffic. But when residents complained about noise, it showed that we need to balance efficiency with people’s well-being.

- London: The number of van trips went down a lot because of micro-consolidation centers, but high real estate costs made it hard to grow.

These case studies show that technical innovation must be paired with political will, fair policy, and sensitivity to local urban ecologies.

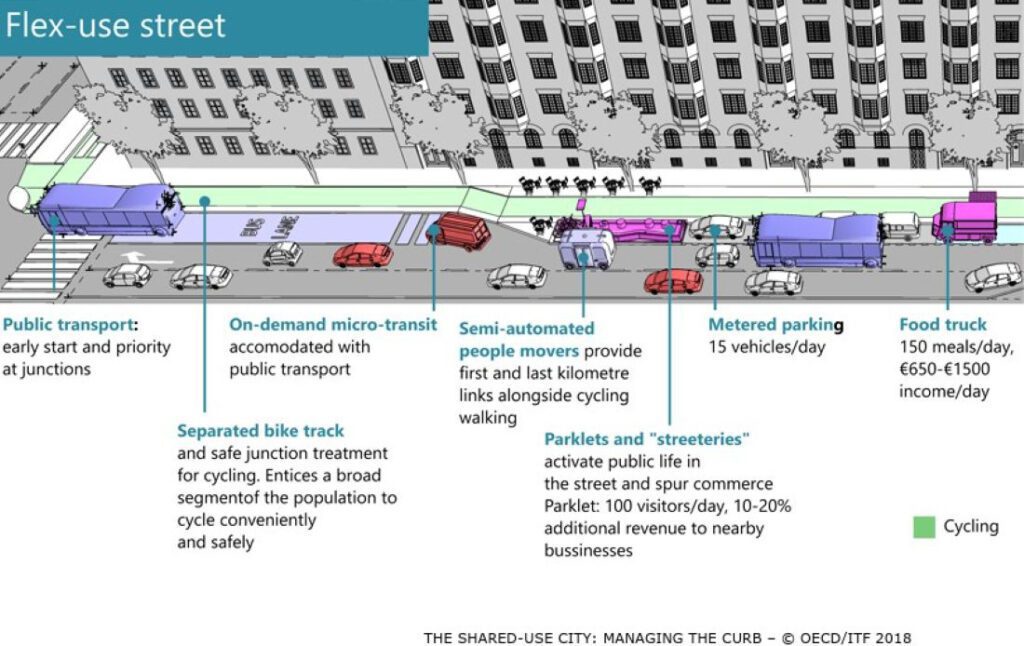

Design Principles for Resilient Delivery Infrastructure

There are several important lessons to be learned from examples around the world about how to think about delivery lanes. Safety is the most important thing. Where deliveries are made should be designed to protect people walking and biking. It’s also important to be flexible. This means making sure that the parking spaces can adapt to changing needs and fit different types of vehicles. Integration with active mobility and public transit networks strengthens connectivity and reduces conflict. It also embeds ecological functionality through measures such as permeable pavement, stormwater planters, and shading. These measures enhance resilience and environmental performance. Finally, these programs should prioritize helping small businesses and neighborhoods that don’t have a lot of resources, just like large corporations. When used together, these ideas can change delivery lanes from being a problem into something that helps the city to be strong and improves life for people.

Policy and Governance: Who Owns the Curb?

One of the most difficult challenges in solving the last-mile mess is governance. Curb space is, by definition, public space. But it has become one of the most contested zones in the city. Companies that provide logistics, ride-hailing services, delivery services, restaurants, residents, and even utility providers are all competing for this limited space. The result is a patchwork of informal practices, double-parking, and enforcement gaps that reduce the curb’s value as a shared public asset.

To deal with this, cities need to take charge of the curb and manage it for the public. This means going beyond unclear signs and random enforcement to clear rules, clear pricing, and consistent oversight by the government. Just as parking meters changed how people used to drive on the street, delivery lane rules now need to change based on how many drivers are using the lanes and how long they wait. It is very important for cities to work with logistics providers, but they must make sure that these partnerships do not make the companies more important than the community. When delivery lanes are managed well, there is less congestion, fewer emissions, and more money to make the system stronger.

The Future of the Street: From Chaos to Coexistence

In the future, streets will be designed to include logistics as a normal part of the design. In this vision, deliveries are intelligently scheduled and coordinated through digitally managed bays. These bays open at certain times of day to minimize conflicts with pedestrians, cyclists, and public transit. The empty space on the street is not just left empty. It is used in a new way that is good for the environment and for people. Bioswales filter stormwater, trees provide shade and help store carbon, and protected bike lanes ensure safe mobility. This approach sees logistics not as something that weakens resilience but as something that strengthens it. It helps cities meet their sustainability goals while keeping goods moving efficiently. In this model, the final part of the journey is no longer the problem that causes traffic and makes life difficult. Instead, it becomes a carefully planned part of city design that makes the air cleaner, the streets safer, and the neighborhoods stronger. This shows that logistics, when planned and designed with intention, can become a key part of sustainable city life.

Conclusion

The problem of getting goods and services to people at the final, last-mile delivery is a defining urban challenge of the 21st century. If we don’t manage them, delivery vehicles can make city streets less safe, less eco-friendly, and less strong. But when we treat last-mile logistics as an opportunity for design, we can make them a key part of sustainable urbanism.

Cities can improve streets and the environment by using dedicated delivery lanes, managing curb space, and using microhubs and cargo bikes. Studies from around the world show the good and bad of these approaches. They show that we need to design with the people in mind and to be fair to everyone. The bigger picture is clear: how a city handles deliveries shows how much it cares about being prepared for the future and protecting the environment. Designing the delivery lane is about more than saving time for delivery people. It’s also about saving the street as a shared space that is good for the environment and for people.

References

- Barcelona City Council. (2019). Superblocks: Barcelona’s model to reclaim public space. Ajuntament de Barcelona. https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/superilles/en

- Conway, A., Cheng, J., Kamga, C., & Wan, D. (2012). Feasibility study of micro-consolidation for urban freight delivery. Transportation Research Record, 2379(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3141/2379-01

- Cui, J., Dodson, J., & Hall, P. (2015). Planning for urban freight transport: An overview. Transport Reviews, 35(6), 701–719. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2015.1038666

- Los Angeles Department of Transportation (LADOT). (2021). Digital Curb Inventory and Management Strategy. LADOT. https://ladot.lacity.org/projects/programs/curb-management

- Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT). (2020). Urban Freight Lab: Final research report. University of Washington Supply Chain Transportation & Logistics Center. https://urbanfreightlab.com/

- World Economic Forum. (2020). The future of the last-mile ecosystem: Transition roadmaps for public- and private-sector players. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/whitepapers/the-future-of-the-last-mile-ecosystem

Seakmy Ty

About the Author

Seakmy Ty is a Cambodian architecture student pursuing a master’s degree in urban planning in France. Originally from Phnom Penh, a city that is rapidly changing due to urban growth, she has developed a deep passion for sustainable urban design and planning. She has received academic training in smart city systems, energy efficiency, and resilience strategies. Seakmy is particularly interested in how design and governance can create cities that balance rapid development with long-term environmental and social well-being.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

Kim Dovey: Leading Theories on Informal Cities and Urban Assemblage

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “