Ecological Urbanism and Inclusive Waterfront Design in Tropical Cities

Tropical cities are facing urgent and intersecting challenges—rising sea levels, intensifying storms, and growing inequality. This article explores how ecological urbanism and inclusive waterfront design can offer long-term, climate-resilient solutions that go beyond surface-level beautification or isolated green projects.

Ecological urbanism reimagines nature not as decoration, but as infrastructure—integrating mangroves, wetlands, and passive cooling into the urban fabric. At the same time, inclusivity demands that waterfronts serve all citizens—not just tourists or developers—by prioritizing public access, cultural relevance, and community resilience. Through global case studies—from Bangkok’s sponge park to the controversial NCICD seawall in Jakarta—the article contrasts visionary and flawed approaches, emphasizing the dangers of copy-paste development that ignores local climate and social context.

To guide better outcomes, it introduces six future-ready design principles rooted in climate logic, social equity, and multifunctionality. These concepts challenge architects, planners, and policymakers to reimagine tropical waterfronts not as exclusive zones or defensive barriers, but as living, adaptive systems—designed for both people and ecosystems to thrive, now and for generations to come.

Paradise Lost, Futures at Risk

Picture a palm-lined waterfront in a tropical city—once a public haven, now fenced off by luxury condos. Floods creep closer each year, heat intensifies under concrete, and the wealthy enjoy sea views while vulnerable communities are pushed inland. Tropical waterfronts—long symbols of paradise—now stand on the front lines of climate breakdown and urban inequality. The latest IPCC report warns global sea levels will rise 0.4 to 0.8 meters by 2100, with extreme floods occurring up to 30 times more often by 2050. Coastal urban centers in Asia, Africa, and Latin America are already experiencing increasing pressure.

Jakarta, for instance, is sinking—by up to 14 feet in some areas—due to excessive groundwater extraction and impermeable surfaces. Nearly 40% of the city lies beneath sea level. At the same time, more than half of the world’s mangroves—key natural coastal buffers—are vanishing, putting $65 billion in flood protection and 775 million coastal lives at risk. These threats are layered: rising seas, vanishing ecosystems, intensifying storms. If ignored, tropical cities risk losing not just beaches, but livability itself. The solution? Reimagine waterfronts as living systems, not concrete barricades—resilient, inclusive, and designed to work with nature.

Source: author

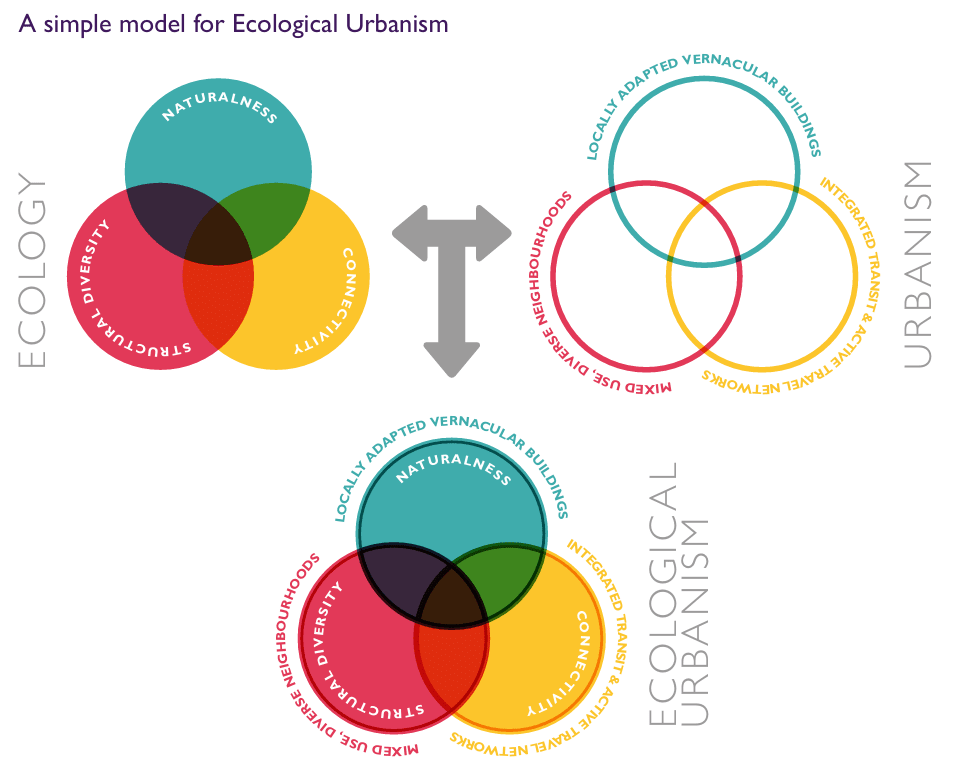

Ecological Urbanism Isn’t Just About Trees

Contemporary cities must be understood as ecosystems—not concrete islands apart from nature. Ecological urbanism moves beyond tree planting; it weaves living processes into the fabric of urban infrastructure. As Anne Whiston Spirn notes, nature in the city is “more than trees and gardens… it is the air we breathe, the water we drink… the earth we stand on.”

This means designing for flows and cycles that sustain life: rain, wind, biodiversity. In tropical cities, it’s not enough to line streets with palms—designs must manage monsoon rains, harness sea breezes, and support urban wildlife. Too often, planners focus on scenic features like rivers, rather than the underlying ecological processes that shape them. Ecological urbanism shifts attention to those processes—tidal exchange, groundwater recharge, pollinator pathways—so that cities work with nature.

Sponge-city strategies blend green infrastructure with daily life: bioswales double as parklets, green roofs cool sidewalks, and coral reef restoration replaces concrete with living coastal defense. In essence, ecological urbanism builds a breathable, adaptive network—embedding air, water, and soil systems into how cities live and grow.

Source: Website Link

Understanding Inclusive Waterfront Design in the Tropics

Inclusive design ensures waterfronts welcome all—rich or poor, young or old, able-bodied or disabled. In tropical cities, where informal settlements and fishing communities often line the coast, equity isn’t optional—it’s foundational. Thoughtful design means adding ramps, wide paths, and clear signage to improve accessibility and safety for everyone. A well-designed waterfront is multi-generational and multi-functional: it can host boat landings, food stalls, play zones, festivals, and open green spaces.

Experts stress that resilient waterfronts must juggle multiple roles—flood control, mobility, commerce, and recreation—while safeguarding public access and economic inclusion. That means saying no to privatized walls and yes to shaded promenades, public docks, and shared markets. For example, urban studies of the Nile River in Egypt emphasize inclusive features like accessible piers, family plazas, and interpretive signage to help all residents engage in city life. In tropical contexts, inclusion also means respecting cultural identity. Waterfronts should make space for fish markets, religious ceremonies, or floating processions—not displace them.

Ultimately, an inclusive waterfront is one where any resident can stroll, fish, pray, play, or simply rest in safety and dignity—transforming the shoreline into a shared civic asset, not a gated view.

Designing in the Tropics Isn’t a Copy-Paste Job

Tropical climates bring heavy monsoons, blistering sun, and sudden storms—conditions that demand design strategies far different from temperate models. You can’t just copy a European park or a New York floodwall and expect it to work in Manila or Mombasa. Instead, successful tropical design adapts to local climate and culture. In Hainan, China, Sanya’s sponge-city strategy tackled monsoon rains through rain gardens, bio-retention basins, and wetlands. These features absorb and slow water on-site, rather than pushing it out to sea. In contrast, Jakarta’s $40 billion NCICD seawall faced backlash for cutting off coastal communities—disrupting fishing livelihoods without fully addressing land subsidence.

Local traditions hold valuable lessons:

- Indigenous stilt houses inspire flood-resilient housing

- Bangkok’s elevated “floodplazas” double as walkable public space

- Cooling through shade and ventilation is crucial: tree-lined streets, breezy open structures, and permeable surfaces help lower urban temperatures naturally.

Each tropical waterfront must be designed specifically for its place—drawing from:

- Local ecosystems (mangroves, coral reefs)

- Cultural patterns (markets, boats)

- And climate realities (typhoons, heat, rain).

As one urbanist notes, tropical cities must “work with nature, not against it”—with every design detail responding to the rhythm of the tropics.

Source: author

Case Study: Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia

Kota Kinabalu (Sabah) illustrates how a tropical waterfront city can plan holistically. In late 2023, KK City Hall launched a Waterfront Masterplan integrated into its 2035 vision, after an international symposium on “water’s edge cities”. The plan explicitly addresses climate threats: it fortifies coastal management infrastructure with both “structural engineering” and nature-based solutions. Planners will expand mangrove belts and tidal parks to absorb storm surges, while also improving public access – continuous seawall promenades, cycling lanes and green corridors, all designed as recreation areas and flood buffers. City leaders emphasize community benefit: the draft calls for more public spaces celebrating heritage, and for disaster-risk projects that also boost tourism and local business.

In practice, this means new boardwalks and plazas that double as flood basins, and waterfront trails connecting neighborhoods. Importantly, Kota Kinabalu’s strategy links renewable energy and public transit (like bike networks) with waterfront design, reflecting an inclusive, multi-function ethos. While still underway, KK’s example shows a tropical city aligning planning, climate adaptation and social goals – a model for other coasts.

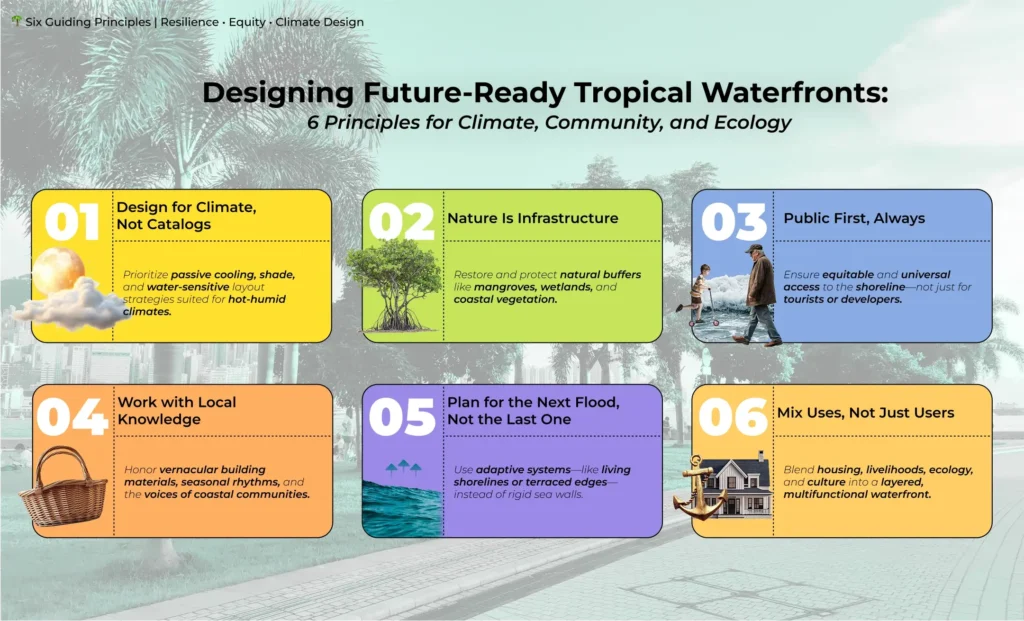

Principles for Future‑Ready Tropical Waterfronts

To build resilient, equitable waterfronts in tropical cities, planners must embrace four interconnected principles:

1. Work with Water (Sponge-City Design):

Capture rainfall where it falls. Use permeable pavements, rain gardens, bioswales, and floodable parks to absorb runoff and reduce street flooding. This approach cools urban heat and replenishes groundwater.

2. Green-Blue Infrastructure:

Restore mangroves, wetlands, coral reefs, and green corridors as living defenses. Nature-based systems reduce wave energy, filter water, support biodiversity, and store carbon—while being more cost-effective than hard infrastructure.

3. Multi-Functional Public Spaces:

Design spaces that serve both daily life and disaster resilience. A boardwalk can act as a floodwall and market; a park pond can store rain and host play. Add inclusive features like ramps, seating, and shade.

4. Social Equity & Engagement:

Involve local communities from day one. Design for livelihoods (e.g., fishing docks) and ensure amenities benefit everyone—especially the underserved. Public input builds ownership and long-term success.

Together, these principles turn tropical waterfronts into living edges: adaptive, inclusive, and regenerative spaces that work with climate—not against it.

Source: author

Conclusion

Tropical waterfronts can become models of ecological urbanism and inclusion, rather than casualties of climate change. By shifting from grey walls to green-blue systems, cities transform floods into resources (the “sponge city” ethos). By designing for inclusive cities, waterfronts open access to all communities, reinforcing social resilience. The challenges are pressing — but the answers are already within reach.

Future-ready tropical harbors will be living landscapes: parks that store stormwater, mangroves that buffer waves, and promenades where families of all backgrounds gather safely. Such designs not only adapt to climate change, they also foster economic vitality and cultural richness. As stakeholders worldwide heed the calls of ecological science and equity, there is hope that tropical cities will reclaim their “paradise,” sustainably and inclusively for generations to come.

References

- C40 Cities. (2021, November 12). Sea Level Rise and Coastal Flooding – C40 Cities. C40 Cities. https://www.c40.org/what-we-do/scaling-up-climate-action/water-heat-nature/the-future-we-dont-want/sea-level-rise/

- Hyde, R. A. (2005). The environmental brief: Pathways for advancing green design. 1–8.

- III, H. (2025). Resilient waterfronts: leading the way toward urban safety, sustainability, and vitality. Arcadis.com. https://www.arcadis.com/en-us/insights/blog/united-states/trevor-johnson/2025/resilient-waterfronts

- Jiang, L., & O’Neill, B. C. (2017). Global urbanization projections for the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Global Environmental Change, 42, 193–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.03.008

- Marcotullio, P. J., Keßler, C., Quintero Gonzalez, R., & Schmeltz, M. (2021). Urban Growth and Heat in Tropical Climates. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2021.616626

- Oginga Martins, Judith & Sharifi, Ayyoob. (2022). World Cities Report 2022: Envisaging the Future of Cities.

- Scottish Wildlife Trust. (2018). Living Cities: Towards Ecological Urbanism (Policy Futures Series, No. 4).

- Team, E. (2023, December 27). Kota Kinabalu focuses waterfront masterplan for sustainable development. © Borneo Echo. https://borneoecho.com/2023/12/27/kota-kinabalu-focuses-waterfront-masterplan-for-sustainable-development/

- Transforming waterfronts for a resilient and sustainable urban future. (2025, April 29). Preventionweb.net. https://www.preventionweb.net/news/transforming-waterfronts-resilient-and-sustainable-urban-future

- UN (2018). World Urbanization Prospects, 2018 Revisions. New York, NY: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs

Kevina Althea Wijaya

About the author

Kevina is a graduate of Architecture from Sepuluh Nopember Institute of Technology. Her interests lie in spatial design, urban environments, and the intersection between architecture and human behavior. Through her design research and creative explorations, she investigates how built environments can foster inclusivity, well-being, and adaptive living.

Related articles

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “