How Phnom Penh’s Riverside and Koh Norea Reshape Public Space in Rapid Urban Growth

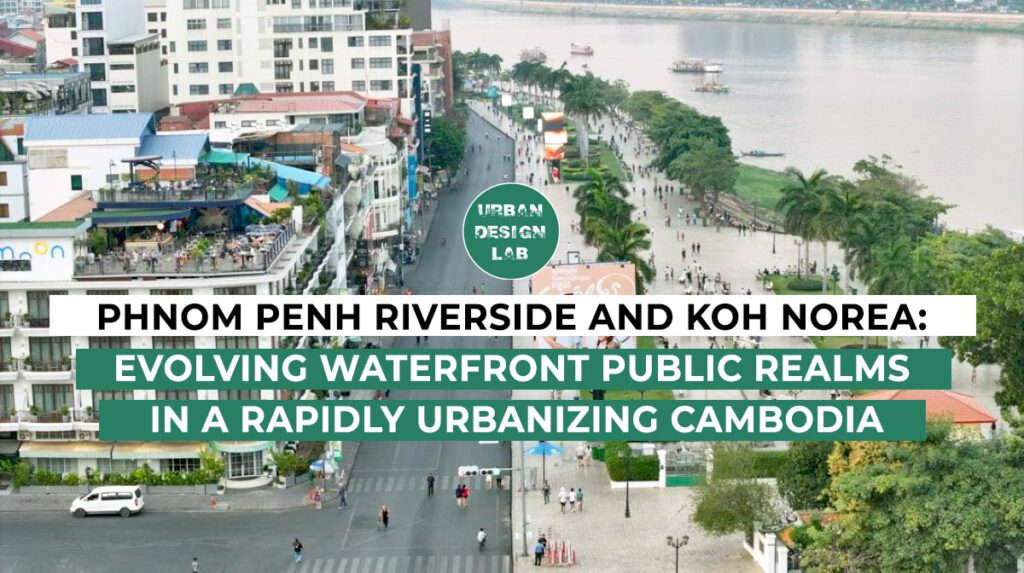

As the capital city of Cambodia grows, Phnom Penh‘s riverfronts have become important places where the city’s history, modern development, and daily life meet. This article looks at two important examples: the historic Phnom Penh Riverside along Sisowath Quay and the newly developing Koh Norea Park on land that was reclaimed from the Bassac River. It looks at how these spaces have changed and what they mean today.

Sisowath Quay is a lively public space that supports informal businesses and cultural activities. The city has made improvements, like Chatomuk Walk Street, a weekend pedestrian zone that creates a flexible, community-friendly space. Meanwhile, Koh Norea has introduced improvements such as stabilizing embankments and improving connectivity. It’s still being developed, but it’s already becoming a popular place for people to visit because it’s pretty and easy to get to.

This article says that Phnom Penh’s changing waterfronts show a move toward urbanism that puts people first. Even though there are still risks related to commercialization and exclusivity, designing for public life is a significant step. To grow in a way that is good for everyone and the environment, we need to balance infrastructure, accessibility, culture, and community participation.

Phnom Penh’s Riversides: The Intersection between Heritage and Rapid Urban Growth

Phnom Penh’s riversides have always been important to the people who live there. For many years, these waterfronts have been places where people can gather, shop, and enjoy performances. In a city where there isn’t a lot of green space, the meeting of the Mekong, Tonle Sap, and Bassac rivers is a vital place for people. People go there for evening walks, sunrise exercise, shared meals, and spontaneous celebrations. For people who live in the city, the riverfront is one of the few places where Phnom Penh feels shared where the differences between social classes and the concrete can temporarily disappear. Mornings, monks walk there. Vendors start their day there. Children play there as the sun sets behind the Royal Palace. These moments, both ordinary and extraordinary, show the important role of the waterfront in society, a place where Phnom Penh’s life can be seen. Phnom Penh’s riverfronts where the Mekong, Tonle Sap, and Bassac rivers meet have always played a key role in the city’s economy, environment, and culture. The capital is growing rapidly, and its waterfronts are changing.

Current Usage & Community Life Along Sisowath Quay, Phnom Penh’s Riverside

Sisowath Quay is the most famous and popular public space in Phnom Penh. This riverfront stretches along the Mekong and Tonle Sap. It has always been a place where people go every day to work and to celebrate. Street vendors, joggers, tourists, families, and cultural performers all share the space. They’ve made it safer and more walkable by repairing the sidewalks, installing new lighting, and adding plants.

One interesting change is Chatomuk Walk Street, where the street is closed to cars on weekends and open to people walking. This change, which makes the public space more flexible and car-free, encourages people of all ages to use the space for walking, dancing, socializing, and playing. It shows that small changes, when made with the community in mind, can greatly improve the vibrancy of urban life. But rising rents and business interests are still a problem. People who live there and people who sell things on the street are worried that building more things will change the people who live there and the things that make Sisowath Quay a fun and open place.

Source: Website Link

Koh Norea Park: A Planned Vision for a New Urban Edge

Across the Bassac River, Koh Norea shows how large-scale urban planning works. The new bridge connecting Koh Pich to Phnom Penh was developed by OCIC. This is part of a larger plan to modernize Phnom Penh’s infrastructure and improve its global image. The site includes luxury residences, a planned skyscraper, and riverside promenades. The raised banks of earth once very weak have been made stronger, which reduces the risk of erosion and flooding. The bridge, which was finished at the end of 2023, has made it easier to get around, reduced traffic, and added more bus routes. Local families have said that the area used to be dangerous and not well-developed, but now it’s stable and getting more welcoming. Koh Norea is already attracting evening walkers, families, and photographers. While it currently lacks the lively atmosphere of Sisowath Quay, its clean, landscaped walkways are becoming a public attraction. The big challenge over time is making sure that as construction continues, the public can still access the area that it’s not going to be blocked by exclusive development.

Designing for People: Comparing Public Realm Strategies in Phnom Penh’s Waterfronts

It’s encouraging to see that the city is prioritizing public spaces along the riverfront. In a city where developers have often put profits before people, Sisowath Quay and Koh Norea now show signs that city planners are starting to think more about how people live together. Sisowath Quay has grown gradually over the years. It has been shaped by the habits of the local people and how they creatively used the space. A good example is the Chatomuk Walk Street initiative, where the riverside is closed to traffic on weekends. This makes it a place where people can walk, families can go, and performers can perform. It’s a way to use public space in a flexible way. It shows that streets are for people, not just cars.

Koh Norea, on the other hand, started from a very different place, a clean slate, built on land that had been reclaimed from the sea. Its wide sidewalks, neat hills, and early landscaping are already drawing families and visitors. It has become a popular place for evening walks and to enjoy the river views. This is something that was not possible in that spot just a few years ago.

Government and Developer Plans: Shaping the Next Chapter

Phnom Penh’s Green Strategic Plan is a plan to add more parks, strengthen the raised banks of earth along the city’s waterways, and make public transportation better. These goals are especially important in a place like the Mekong Delta, where flooding is common. These goals also match the national goals of organizations like the Mekong River Commission. OCIC is still leading private investment in Koh Norea, promoting luxury towers and commercial corridors. While these projects may help the economy, researchers in cities warn against real estate-led models that risk excluding everyday citizens (Shatkin, 2017). It will be essential to keep Phnom Penh’s riverfronts genuinely public. This will require ensuring open access, space for informal economies, and cultural activities.

Navigating the Next Chapter for Phnom Penh’s Riverfronts

Phnom Penh’s waterfronts show how the city’s priorities have changed over time. At first, people focused on survival and trade. Later, they started to enjoy recreation and wanted to be resilient. Now, they want to create a strong urban identity. Sisowath Quay shows how small, community-centered design and flexible space management can encourage inclusive urban life. Koh Norea shows how planning and infrastructure can create new possibilities. It also shows the challenge of including cultural authenticity in new buildings. Now is the time to build on these early successes. Making it easy for people to walk there, having events, and protecting the people who sell things there can make sure that riverfronts remain spaces for all. If the city plans carefully, its waterfronts can become places where history, nature, and daily life all come together.

Conclusion

Phnom Penh’s riversides are an important part of what makes the city what it is. Sisowath Quay is a lively and inclusive gathering place that is a part of everyday life, while Koh Norea shows the potential of modern infrastructure to change the city. These different spaces also show how important intention is. Building a walkway is not enough. It’s how people use it that makes it valuable. Public spaces are successful not only because they are beautiful, but also because people use them. Phnom Penh has made big progress by designing for people from informal vendors to evening strollers. Projects like Chatomuk Walk Street and the early popularity of Koh Norea’s promenades show that thoughtful, flexible, and inclusive design is possible. As the city continues to grow, it must do more than just build; it must also invite people to come. Phnom Penh can keep its riverfronts affordable, promote local culture, and protect public access. This would ensure that the riverfronts are shared spaces where all residents feel welcome.

References

- Mekong River Commission. (2023). State of the Basin Report 2023. https://www.mrcmekong.org/

- Shatkin, G. (2017). Cities for profit: The real estate turn in Asia’s urban politics. Cornell University Press.

- Open Development Cambodia. (2023). Sisowath Quay. https://opendevelopmentcambodia.net/tag/sisowath-quay/

- Gehl, J. (2010). Cities for people. Island Press.

- Khmer Times. (2023, October 12). Koh Norea – Appealing to new residents and developers in Phnom Penh. https://www.khmertimeskh.com/501466584/koh-norea-appealing-to-new-residents-and-developers-in-phnom-penh/

- Phnom Penh Post. (2023, November 22). Riverbank worries vanish: Koh Norea’s development success. https://www.phnompenhpost.com/national/riverbank-worries-vanish-koh-norea-s-development-success

Seakmy Ty

About the author

Seakmy Ty is a Cambodian architecture student pursuing a master’s degree in urban planning in France. Originally from Phnom Penh, a city that is rapidly changing due to urban growth, she has developed a deep passion for sustainable urban design and planning. She has received academic training in smart city systems, energy efficiency, and resilience strategies. Seakmy is particularly interested in how design and governance can create cities that balance rapid development with long-term environmental and social well-being.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “