How Riverfront Projects Are Transforming Urban Streetscapes

Urban rivers, once central to everyday life and cultural identity, have often been marginalized by industrialization and rapid modernization. This article critically examines how cities across the globe are reimagining their riverfronts, not just as aesthetic enhancements, but as strategic public spaces that reconnect ecology, community, and economy. Through a comparative lens on San Antonio, Sabarmati, Cheonggyecheon, and Pittsburgh, the piece explores how riverfront redevelopment influences spatial experience, cultural continuity, and environmental resilience. It raises crucial questions about displacement, ecological sensitivity, and inclusivity, ultimately arguing for context-sensitive, multifunctional, and human-scaled riverfronts as the true future of urban transformation

Riverfronts Through Time: Culture, Commerce, and Crisis

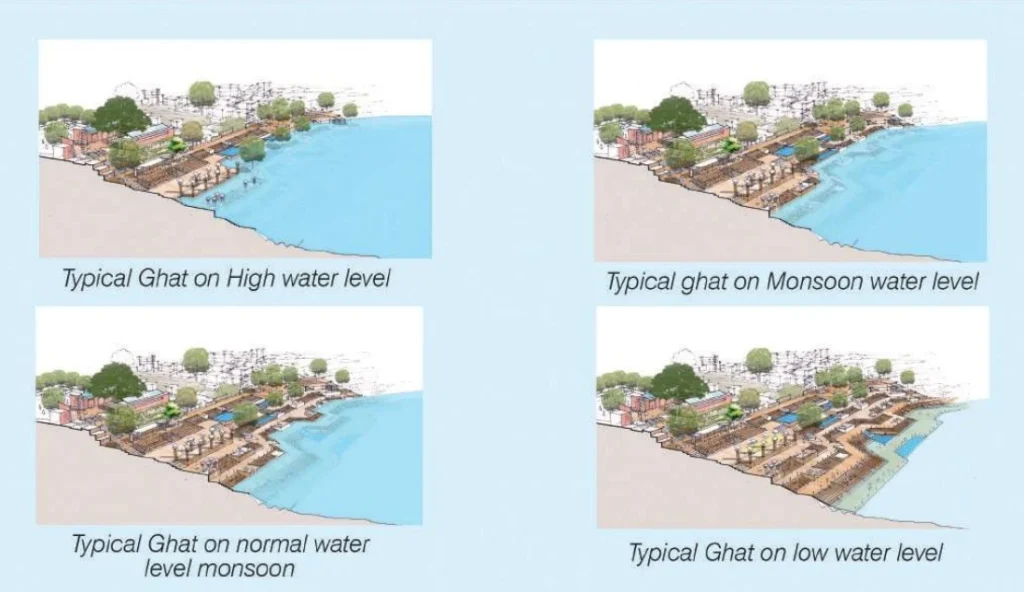

Riverfronts have historically served as the cradle of civilization, providing water, transport, and fertile land; In essence, life revolved around it. Across Asia, Africa, and South America, rivers were not only essential for sustenance but also deeply embedded in everyday life. In ancient Indian cities, Ghats along the rivers hosted interaction between water and people: ablutions, cremations, festivals, storytelling, and commerce. The river was not a backdrop, but it was the centre stage of urban life (Vriddhi, 2017).

Similarly, in Mesopotamia and Egypt, rivers shaped settlement patterns, religion, and trade. Riverbanks were shared commons that connected people to spirituality and civic engagement.

In contrast, European and North American cities underwent a different arc. Rivers like the Thames (London), Seine (Paris), and Hudson (New York) initially supported commerce and market life. However, the Industrial Revolution transformed them into logistical corridors, dominated by factories, ports, and railway sidings (Mehta & Oza, 2023). These once-vibrant public edges became polluted and inaccessible. During the late 20th century, these cities began to reclaim their riverfronts through urban renewal projects, giving birth to the modern concept of “Riverfront Development”.

Are we truly developing our urban riverfronts, or are we, under the guise of progress, accelerating their degradation?

Rivers in Culture and Memory: The South Asian Story

Riverfronts in South Asia have traditionally embodied the idea of “heritage riverscapes”, urban landscapes shaped by oral history, seasonal rhythms, and fluid spatial arrangements (Szibbo, 2020). These settings embraced multifunctionality, serving as informal marketplaces, festival grounds, spiritual centers, and water access points. The ghats of Varanasi and Pushkar are examples where architecture emerged from continuous dialogue with the river. Unlike rigid embankments, these riverscapes accepted monsoon cycles and daily changes in use, becoming deeply ingrained in the culture and geography. (Vriddhi, 2017).

Yet, modernist planning in Global South cities has often overwritten this adaptive logic with hard, singular-use designs modeled on Euro-American templates. In attempting to look “developed,” many cities are turning away from culturally sensitive riverfronts to disconnected public zones (Szibbo, 2020). This shift toward commercialized “river beautification” threatens to erase heritage riverscapes under hardscape and uniformity.

Source: Website Link

The Illusion of Concrete Order

However, as cultural memory gives way to modernist ideals, riverfronts are increasingly cast in concrete, both literally and figuratively! Concrete embankments, often marketed as symbols of progress, carry deep ecological and social costs. While they offer a clean, controlled edge, they disrupt riparian habitats, reduce groundwater recharge, and cut off people’s relationship with the river. The Sabarmati Riverfront exemplifies this trade-off, showcasing a manicured river edge but at the cost of ecological continuity and cultural resonance.

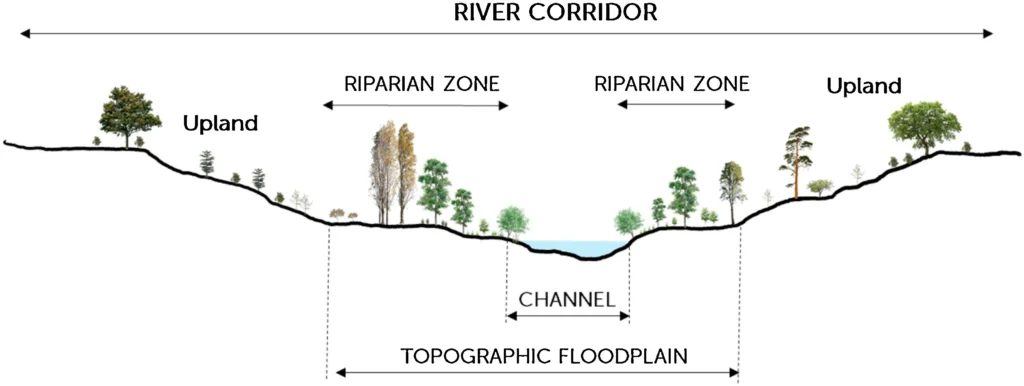

In contrast, the Pittsburgh Riverlife Guidelines offer a more integrated vision, advocating riparian buffers with vegetative edges, trails, and habitat corridors that evolve with natural rhythms (Riverlife, 2016). These soft-edged designs not only support flood resilience and biodiversity but also create adaptable public spaces that foster seasonal and daily use.

San Antonio Riverwalk, USA - Tourism and Placemaking

The San Antonio Riverwalk is one of the most iconic examples of waterfront urban transformation in the United States. Initially conceived as a flood control measure following a devastating flood in 1921, the project transformed a neglected downtown river channel into a vibrant linear park. Before redevelopment, the river was hidden, surrounded by narrow walkways and inaccessible service alleys.

Today, it features restaurants, shops, cultural spaces, and boat tours that attract millions annually. Streetscapes once dominated by asphalt and utilitarian back-of-house functions have become walkable, human-scaled corridors lined with vegetation, lighting, and seating. It effectively redefined San Antonio’s urban identity, prioritizing walkability, public art, and tourism (Mehta & Oza, 2023).

However, it has also been criticized for prioritizing economic development and tourism over ecological integration and its resilience to climate change. While San Antonio leveraged placemaking for tourism and urban branding, other cities have approached riverfront development as a means of asserting control over perceived disorder.

Sabarmati Riverfront, India - Order, Access, and Exclusion

Ahmedabad’s Sabarmati project represents a model of urban renewal that prioritizes cleanliness, order, and aesthetics. Unlike San Antonio’s walkable festivity, Sabarmati’s transformation stems from a desire to erase informality and regulate flow. Before its transformation, the Sabarmati was often dry for much of the year, with settlements and vendors concentrated on its informal and cluttered banks. It faced challenges of encroachment and pollution.

The redevelopment introduced a 10.4-kilometer-long concrete embankment, regulating the river’s width and flow. It added promenades, green belts, cultural plazas, and event spaces, significantly improving sanitation and flood control. The formerly fragmented streetscapes were converted into continuous, well-paved, and landscaped corridors that invite pedestrian use. The project is celebrated for reactivating a polluted and underutilized river corridor.

However, it has been critiqued for displacing over 14,000 informal residents and for losing the river’s organic and ecological edge (Vriddhi, 2017). The uniformity of its design reflects aspirations for global aesthetics but overlooks local practices, river rituals, and ecological flexibility. Where Sabarmati imposed control through embankments, Seoul charted a radically different path by removing infrastructure altogether to restore a buried stream.

Cheonggyecheon Stream, South Korea - Restoration and Urban Healing

Cheonggyecheon’s transformation involved tearing down a highway to reveal an old watercourse, replacing cars with people and concrete with ecology. It’s a benchmark in environmentally responsive urbanism that prioritizes healing over hardscaping. Originally a natural stream, it was buried beneath concrete and an elevated expressway in the 1950s during South Korea’s rapid industrialization. By the early 2000s, the structure was deteriorating, and the surrounding streetscape suffered from congestion, pollution, and disuse. In 2003, the city undertook a bold plan to remove the expressway and uncover the stream.

The restored Cheonggyecheon now runs 5.8 kilometers through downtown Seoul, flanked by walkways, vegetation, and stepping stones. The urban environment has shifted from a car-centric corridor to a pedestrian-friendly linear park that cools the microclimate and supports biodiversity (Landscape Architecture Foundation, 2023).

Streets that once choked with traffic now host art installations, street performances, and public gatherings. The project renewed economic activity and improved environmental health, but also raised concerns over cost, gentrification, and the displacement of informal street vendors. Despite these, it remains a benchmark for environmentally responsive, restorative, and people-centered urban transformation.

Pittsburgh Riverfront, USA - Post-Industrial Renewal

Back in the early 20th century, Pittsburgh was a drastically different city. It was dirty but more populous. The Point was an industrial zone through the early 1900s due to its convenient location at the confluence of three rivers. The area deteriorated to a slum by the 1940s.

Pittsburgh has turned its post-industrial riverfronts into celebrated public assets through its Riverlife initiative. The city implemented soft edges, ecological corridors, and a network of public trails, integrating green infrastructure and placemaking principles (Riverlife, 2016).

The project has catalyzed $4 billion in adjacent development, showcasing how environmental design can foster economic and community revival. However, ongoing challenges include ensuring equity and preventing exclusion in redeveloped neighborhoods.

Transformation of Urban Life and Lifestyle

Taken together, these case studies demonstrate that riverfront development is not just about reshaping land, but it also reshapes livelihoods, lifestyles, and the very identity of a city. Globally, such projects have redefined how cities interact with their rivers, turning once-abandoned or polluted edges into thriving public destinations. These transformations have boosted tourism, increased property values, generated jobs, and improved local business ecosystems.

For instance, the San Antonio Riverwalk attracts over 14 million visitors annually, contributing significantly to the city’s tourism economy and hospitality sector (Mehta & Oza, 2023). Walkability and safety enhancements have improved the quality of life and pedestrian engagement in the downtown core. Similarly, the Cheonggyecheon project not only restored ecological balance but also increased business activity by 3.5% in the surrounding area while reducing temperatures by up to 3.6°C in the vicinity (Landscape Architecture Foundation, 2023). The Sabarmati Riverfront not only brought new economic activity to a once-polluted riverbank but also created a cultural hub and an identity for the city (Vriddhi, 2017).

These projects highlight that riverfronts do more than beautify cities; they create hubs of social life, cultural exchange, and economic opportunity, which are directly linked to mental well-being and urban satisfaction (Yu et al., 2025).

Designing the Ecological Edge

True ecological design requires riparian buffers that are no less than 75 feet wide (23 meters), with three zones: undisturbed forest closest to the river, managed woodland, and upland buffer to absorb and filter runoff (Riverlife, 2016). These zones not only filter pollutants but also reduce flood risks and create biodiverse urban spaces.

To support multifunctionality, riverfronts should integrate softscape, mobility, recreation, informal economies, and cultural representation. Riverfront spaces that support walking, sitting, engaging with art, or participating in religious events foster deeper urban attachment and well-being (Riverfront Public Realm, 2015).

Placemaking at the Water Edge

Unlike the days of Industrialization, cities no longer treat riverfronts as neglected urban margins; they are the symbolic and social front yards. Around the world, well-designed riverfronts are creating opportunities for everyday urbanism: open-air markets, festivals, food stalls, walking trails, cycling paths, and public art. These spaces are the vital settings for civic expression, relaxation, and meeting (Yu et al., 2025). Also creating new visual and physical connections to water, and economic activation of river-adjacent roads.

Recent human perception studies show that riverfronts with green elements, open views, and multifunctional programming are rated higher in terms of safety, beauty, vitality, and walkability. Excessive concrete designs lead to feelings of detachment or discomfort (Yu et al., 2025).

Designing for placemaking means creating spaces that encourage interaction and a sense of belonging. Be it Seoul’s eco-restoration efforts or San Antonio’s festive spine, riverfronts bind city life together across class, culture, and age group.

Eco-sensitive riverfront developments in the future will be the backbone that quietly sustains the life of the river as well as the city.

Conclusion

Around the world, riverfront development projects are no longer mere beautification efforts; they are strategic urban interventions that shape how cities live, grow, and are remembered. Once-polluted and neglected riverbanks have been reimagined as walkable corridors, cultural stages, and ecological buffers. Streets that once turned their backs to rivers now embrace them, reconnecting urban life with flowing water.

Yet, this transformation is not without risks. When riverfronts are over-engineered, commercialized, or designed without local context, they lose the very essence that makes them meaningful. Ecological degradation, displacement, and cultural erasure continue to shadow projects that prioritize control over coexistence.

The true challenge lies in designing riverfronts that honor both the river and the people who depend on it, cherish spaces that evolve with seasonal flows, support everyday life, and invite collective memory.

A beautifully paved promenade means little if the river beneath it is dead or disconnected. Riverfronts must become places where ecology, culture, and community not only coexist but thrive together. The future of urban riverscapes depends on this delicate balance.

References

- Szibbo, N. (2020). Heritage riverscapes and the dangers of modernist erasure in riverfront development. Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review, 31(2), 35–46.

- Riverfront Public Realm. (2015). Riverfront development: A public realm and its adaptive strategies. Retrieved from Riverfront_Development_-_A_Public_Realm_Its_Adapta.pdf

- Mehta, R., & Oza, J. (2023). Riverfront development: A tool to improve and restore urban green spaces. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET).

- Vriddhi. (2017). Riverfront development in Indian cities: The missing link. GSTF Journal of Engineering Technology.

- Riverlife. (2016). A guide to riverfront development. Pittsburgh: Riverlife Foundation.

- Landscape Architecture Foundation. (2023). Cheonggyecheon stream restoration. Retrieved from https://www.landscapeperformance.org/case-study-briefs/cheonggyecheon-stream-restoration-project

- Yu, Y., Huang, G., Sun, D., Lyu, M., & Bart, D. (2025). Exploring the impact of waterfront street environments on human perception. Buildings, 15(10), 1678. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15101678

Aaditya Kuyyamudi

About the author

Aaditya Kuyyamudi is an architecture student at Manipal School of Architecture and Planning, exploring how urban design can spark inclusive, walkable, and climate-resilient cities. His work reimagines streets as stories and cities as vibrant, equitable public realms shaped by community and sustainability.

Related articles

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “

One Comment

Riverfront development has so often been associated with beautification and accessibility to the urban residents, without much attention paid to the ecological system of water. However, there is an argument to developing rivers and streams, for most urban water bodies are already devoid of health ecosystems. Coupled with the postcolonial development trends, most economically secure hubs such as cities in the USA or S Korea have the ability to divert funds and resources to not just reimagine the riverfront, but also maintain long-term sustainability within communities. This will be a challenge in the global south, given the stress faced by ‘urban commons’ and poor governance strategies. This will be a very interesting topic to dive into in a Global South (forgive me for a lack of better description) viewpoint and study the potential of water body developments in urban giants such as Mumbai and Chennai, whose rivers are currently part of a larger sewage system and serve no socio-ecological value.