Journalist Colony Park, Chennai: Neighborhood park as a Community Lifeline

The article is a comprehensive documentation of a local recreational park in the residential area of Thiruvanmiyur, Chennai. Located in the Journalist Colony, it finds its purpose as more than a protector of disappearing green spaces in the urban area—it is a hub of activity and socialization.

The article dives into the physicality and programmatic zoning of the park and how each zone contributes to the multi-faceted and flexible park seen today. Indigenous plant species are highlighted to show commitment to conserving local biodiversity. The need for such parks is explored in relation with the women and the elderly. Jane Jacobs’ ‘Eyes on the Street’ concept is applied here to explain the natural surveillance and safety of the park.

Ultimately the park is identified as the heart of the community, and it advocates for the creation and preservation of more ‘small’ parks, which have a magnified impact on society.

Introduction

Idyllic roads with small temples tucked into a corner alongside tall churches and mosques as traffic buzzes its way. Soft crashing of waves provides soothing music to people relaxing on the glistening sand accompanied by scurrying crabs. British colonialism is woven into the plaids of native Madras checks. Almost 5 million people call the city their home, but locals would argue it is much more than that. Situated along the coastline of this city is the locality Thiruvanmiyur.

The largely residential area is known for Marundeeswarar Temple and is the seat of Kalakshetra Foundation, where traditional art forms are preserved with each beat and step. Tucked away into this vicinity is the Journalist Colony, a residential area initially reserved for journalists. One is greeted with the perpetual chirping of birds loud enough to drown out automobile noises and glimpses of sky peeking through dense tree branches.

Bordered by the state highway East Coast Road on the west side and Kottivakkam Kuppam Road on the east side, this area contains the Journalist Colony Park. This article explores the park as an anchor of community and relationship, especially in a city with disappearing green spaces and increasing isolation.

Source: author

Need for public parks

Parks are more than a way for people to get outdoors; they are facilitators of social connection and protectors of ecosystems in the hearts of cities. It is especially necessary in a city like Chennai, which has not been naturally bestowed with lush gardens like Kashmir. Chennai has the lowest green cover of 15% compared to all metropolises of India and only 0.81 square meters of open space per capita when WHO’s guidelines are 10 to 12 square meters per capita.

Historically, streets were places of conversation and community. The architecture of houses reflected this. Thinnai was the raised platform of transition space between the street and the home running around the entire frontal elevation. It offered people a place to sit and converse, solidifying the street as a social glue. However, as the British made wraparound verandahs and automobile-based road construction commonplace, the thinnai slowly disappeared.

In such dire situations, protecting the existing 250 parks of Chennai is of utmost importance. Built and maintained by Greater Chennai Corporation, the unique shape of the park can be attributed to placing more importance on the development of houses on the challenging land.

Source: Website Link

Physicality

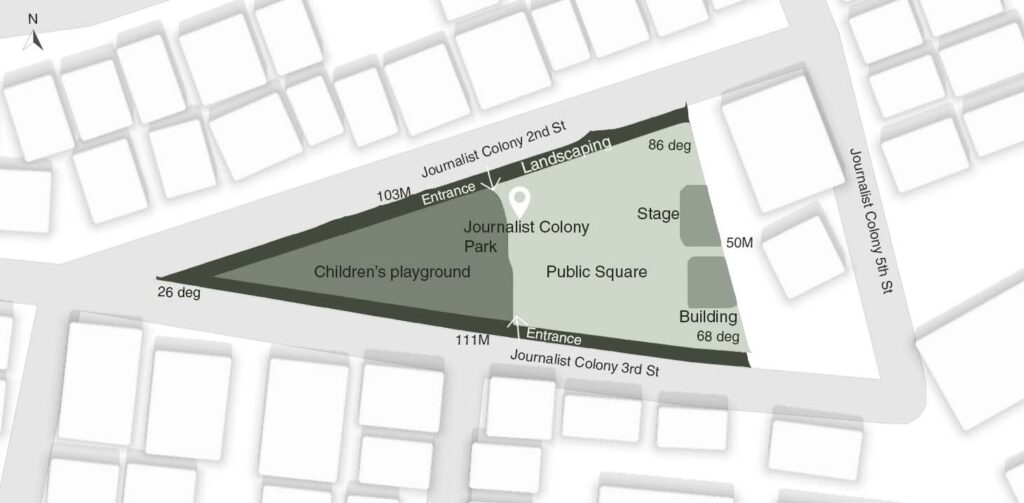

The park can be classified as a recreational park with major hardscape and landscaping at the edges. The triangular plot of land is located 60 meters away from the Kottivakkam Kuppam road. The sharply angled west corner has been effectively dealt with by chamfering the walkway and creating a playground.

The park is paved with weathered grey hexagonal concrete blocks and has two layers framing it—the outermost green layer with trees and shrubs and the inner paved walkway. There are two entrances at the center, one from Journalist Colony Second Street and the other from the third street. The gate is approximately 3 meters wide, allowing bicycles and maintenance carts to enter.

Designed to be a multi-functional space, the park’s zoning can be effectively split into two: a public square, such as a stage and the association’s building at the east, and a children’s playground at the west. The public square is fully paved, whereas the children’s playground has exposed sand, the duality serving the necessary purpose of gathering and play. The bending of the walkway in the children’s playground invokes a sense of playfulness, creating the interesting experience of a serpentine way of movement.

Source: author

The public square

The public square consists of the stage, paved ground, and building for the Central Journalist Colony’s Welfare Association.

The central stage with steel framing measures 10 meters x 5 meters and is clad with bright and colorful blue diamond-patterned tiles, effortlessly drawing attention due to materiality and placement. At a height of 0.6 meters, it is accessed by a flight of four staircases on either side. It is well equipped to host small-scale events and, along with the paved ground, turns the simple park into a community gathering spot.

The open paved ground offers flexibility in usage. Surrounded by park benches, it finds its use for a variety of activities, from badminton court to seater during events. The benches facing the ground allow caretakers to keep an eye on the children during play, creating safety via visibility.

The park also functions as the home office of the Central Journalist Colony’s Welfare Association with a ground-plus-one building on the right side of the stage. The prime location of the park and its features make it the ideal place for the office—open paved ground offers space for larger-scale meetings to be held.

Source: author

Children’s playground

It is not an overstatement to say that the children in the locality grew up in this park. The evening timings of 4 to 9 see kids of all ages teeming the park with the equipment in full swing. Caretakers take this as an opportunity to catch up with each other, relaxing and bonding while watching them.

The bright color palette of the recreational equipment has a psychological role in the relaxation of the children. The overarching use of green and yellow induces a joyful mood and reflects nature, and the combination creates a calming environment. The minimal use of blue and red creates a contrast to the green surroundings, drawing the kid’s attention to the slides.

The installations with the same function have been clustered together and arranged in a way to allow visibility and are carefully designed with curved edges to reduce accidents. The spacious layout has been designed with child psychology in mind, leaving room for running and gathering.

Compacted sand flooring connects the children to nature and prevents slipping. The materiality of plastic and steel aids in better maintenance. Services such as manholes and drain holes in paved areas show inclusion of functionality.

Source: author

Flora and Fauna

Indigenous landscaping is a method of framing the park. Tall trees with wide foliage are located at the outermost edge, offering shade and respite in the hot climate. They are subsequently lined by below-knee-level shrubs, which include both flowering and non-flowering. Young saplings are planted on an inner frame after the walkway, creating a minor visual division.

Examples of flora present in the park:

- Neem tree—a fast-growing tree with wide foliage; its health benefits are numerous, and it is used for a variety of products from tea to skin salves.

- Cannonball tree—The notable tree with spherical fruits is a native of the rainforests of Central and South America but has found religious significance in India.

- Ashoka tree—The native tree is revered in many religions and has remarkable ayurvedic properties.

Squirrels are often spotted scurrying around the park as butterflies and bees provide beautiful visuals. Street dogs find a haven amidst the dangerous traffic-filled roads, and it is not uncommon to see them dozing off on the cool soil. The cawing of crows dominates the avian population, but the presence of a rare house sparrow proves the park is doing right in preserving biodiversity.

Source: author

A safe haven for women and the elderly

According to the WHO physical activity profile of India in 2022, women were more physically inactive than their male counterparts. 44% of women were inactive compared to 28% of men in adults aged 18+. The imbalance increases in senior citizens, with 60% of women being inactive compared to 38% of men in adults aged 70+.

Reasons for this include conservative norms on women’s leisure time and increased domestic responsibilities. In such cases where women are deterred from going to the gym and prioritizing their health, parks provide an invaluable resource.

As it is more societally acceptable, it is common to see women, especially elderly women, make use of the sensory pathways and open-air fitness playground. From 5 am to 10 am, elderly people can be spotted taking a stroll around the park and using its facilities to improve their health. After 9:00 am, homemakers, after completing their daily chores, are offered an opportunity to connect with others and exercise, which provides a major relief amidst their busy lives.

In these cases, parks prove indispensable to women. They offer free exercising and give them breathing space amidst their busy lives.

Source: author

Eyes on the park

Jane Jacobs’ ‘Eyes on the Street’ concept refers to natural surveillance generated by people who use the public space or observe it from their home, achieved via visibility in design. This surveillance leads to better safety and security. This concept can be applied to this park, where visibility is one of the main design principles.

Houses are arranged around the park, facing it. The fence separating the park from the street is mostly void, with a frame of tall trees whose foliage is well beyond at least 3 meters in height. These factors combined provide the surrounding houses with unconcealed views of the park. Residents can watch it from the comfort of their houses, providing surveillance no machine can match.

Inside the park, the play units are arranged in such a way that compact ones are near the center and the taller ones are at the edge. This provides good visibility from the center, reinforced by the walkway that wraps around the park.

The design geared towards transparency has created a park that has high levels of safety due to a shared sense of vigilance.

Source: author

Conclusion

Though the park may be small compared to larger ones like Semmozhi Poonga in Chennai, it has proved itself as the lifeline of the community. The duality of the park makes it a multi-use, flexible space capable of hosting events aligning with national celebrations while catering to everyday use.

People of all ages find respite in the open space. It is a crucial node of the neighborhood where social life thrives, and good health is maintained. It is a preserver of local biodiversity in a fast-developing city where nature is destroyed to make way for buildings. Natural supervision achieved via visibility aids in establishing the park as a safe place.

Minor improvements such as adding a roof to the stage make the park weatherproofand offer greater flexibility for gatherings. Additions of a sensory walkway and open-air fitness ground are successful in improving the well-being of people, especially women and senior citizens.

The park is a stronghold of social and urban fabric working to preserve local biodiversity. For many it is so much more than that; it is a sanctuary from their hectic lives, offering moments of calm and fellowship.

References

- Olsen, B. (2023, January 24). The perks of parks through the lens of Chennai. Chicago Policy Review. https://chicagopolicyreview.org/2021/04/06/the-perks-of-parks-through-the-lens-of-chennai/

- (2022, June 9). CMDA goes the extra mile to protect Chennai’s open spaces. The Times of India.

- Physical activity India 2022 country profile. (n.d.). World Health Organisation https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/physical-activity-ind-2022-country-profile

- Sadanand, Anjali & Nagarajan, R.V.. (2020). Transition Spaces in an Indian Context. ATHENS JOURNAL OF ARCHITECTURE. 6. 193-224. 10.30958/aja.6-3-1.

- Crestani, Andrei & Pontes, Brenda. (2018). THE PUBLIC SPACE (IN)VISIBLE TO THE EYES OF JANE JACOBS.

Vijetha Ravindran

About the author

Vijetha Ravindran is an undergraduate student of architecture at Thiagarajar School of Environmental Design and Architecture, Madurai, India. From Chennai, her interest in design rose from exposure to different built environments due to frequent traveling in her early years. Her main interest in research is about the use of artificial intelligence in the allied fields of design and architecture and placemaking to build people-centric cities. Her work reflects a commitment to people-centric buildings and designs with an emphasis on spatial experience.

Related articles

UDL Illustrator

Masterclass

Visualising Urban and Architecture Diagrams

Session Dates

28th-29th March 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “