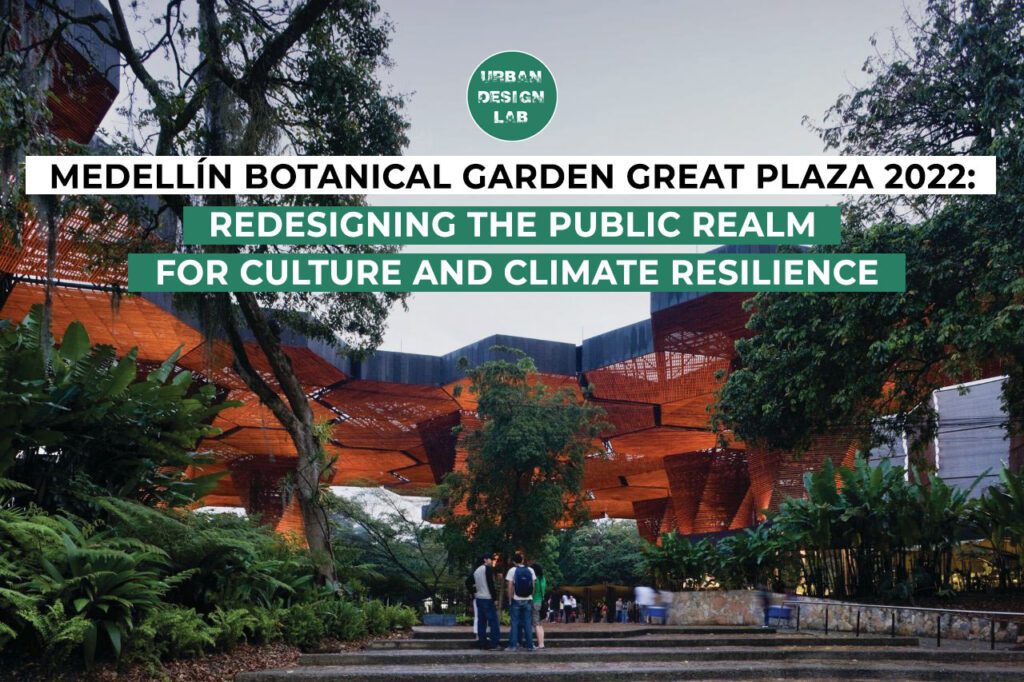

Medellín Botanical Garden Great Plaza 2022: Redesigning the Public Realm for Culture and Climate Resilience

This article explores the 2022 redesign of the Great Plaza at the Joaquín Antonio Uribe Botanical Garden in Medellín, Colombia. The plaza, once an underutilized, heat-absorbing expanse of concrete, underwent a transformation into a vibrant, multifunctional civic space that addresses both ecological imperatives and cultural needs. The Great Plaza occupies a pivotal position at the intersection of urban and natural environments, functioning as a crucial nexus between urban life and botanical ecology. This remarkable space offers a multifaceted setting for diverse activities, all within a meticulously designed architectural framework that prioritizes environmental sustainability. The article commences by situating Medellín’s Great Plaza within its historical and urban context, emphasizing its initial deficiencies as a transitional, underutilized space. The subsequent analysis examines the plaza’s 2022 transformation through a multidisciplinary lens, emphasizing passive climate strategies such as bioswales, permeable paving, and shaded structures, in conjunction with culturally grounded, community-led design. Notwithstanding the challenges faced, including logistical constraints, stakeholder negotiations, and ecological preservation, the project yielded a socially inclusive and environmentally resilient outcome. The redesigned plaza, firmly anchored in Medellín’s legacy of civic innovation. It exemplifies the convergence of climate adaptation, cultural identity, and architectural subtlety in contemporary urban design.

From Passive Forecourt to Urban Void: The Great Plaza Before 2022

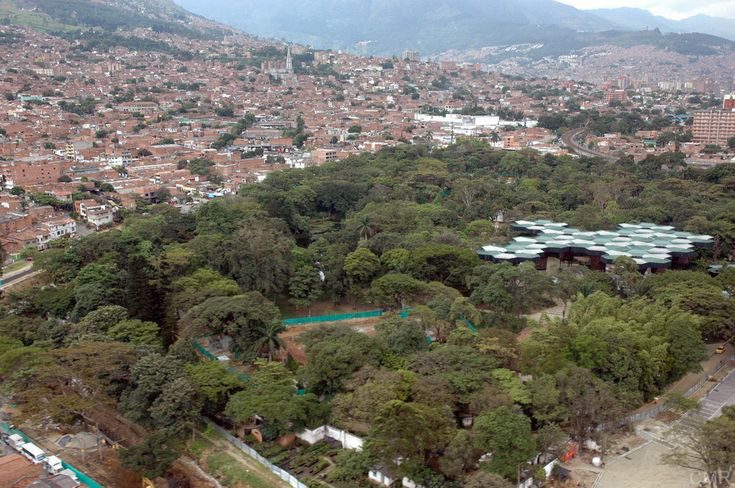

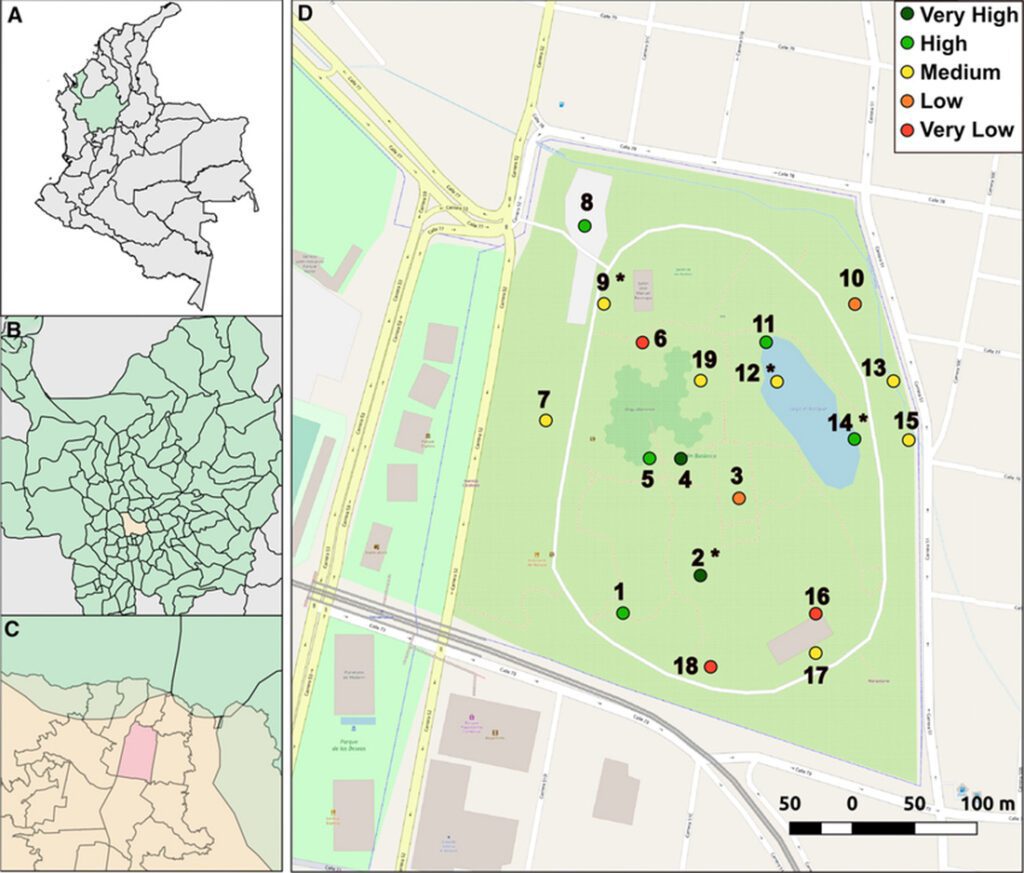

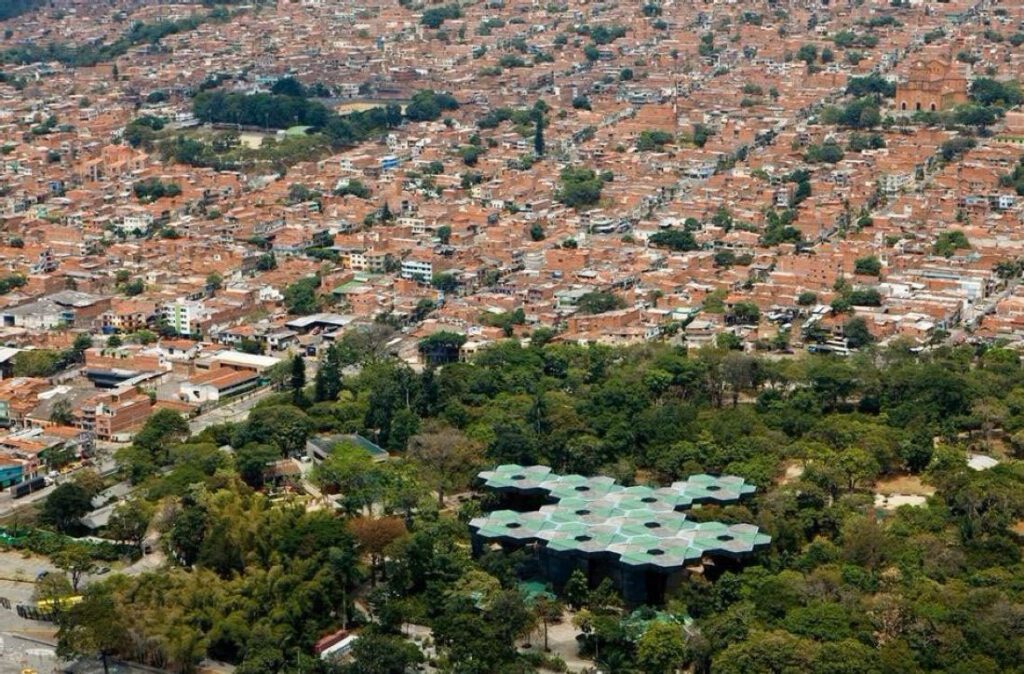

The Joaquín Antonio Uribe Botanical Garden is located in the northern zone of Medellín, Colombia. It is part of a dynamic cultural and ecological corridor that includes the Park of Wishes and Explora Science Center. The Great Plaza, situated at the garden’s primary entryway, initially functioned as a transitional forecourt—a spacious, paved expanse connecting the city to the garden’s interior.

Developed in the early 2000s as part of Medellín’s initiative to enhance civic infrastructure, the plaza was intended as a venue for public gatherings and a nexus for community connectivity. However, it evolved into an expansive, underutilized space characterized by impermeable concrete, lack of vegetation, and exposure to sunlight. The static layout and absence of shade or programming offered little encouragement for social interaction or cultural activity. Significantly, the plaza stood in contrast to surrounding areas that reflected Medellín’s evolving identity as a city of social and ecological transformation. As climate conditions intensified and urban life demanded more adaptive environments, the Great Plaza’s outdated design marked a missed opportunity. These limitations became a catalyst for the 2022 redesign, part of a broader ambition to create a public realm responsive to cultural life and environmental realities.

A New Civic Heart for the Garden and the City

The redesign of the Great Plaza in 2022 aimed to transform this underperforming space into a significant civic landmark. The redesign envisioned a space capable of facilitating cultural exchange, environmental education, and climate-conscious design. Rather than implementing a purely botanical intervention, this project treated the plaza as a hybrid: a public square within a garden, and a garden within a public square.

The collaborative efforts of architects and landscape designers resulted in the creation of a modular, climate-responsive, and socially inclusive environment. The redesign incorporated shaded walkways, bioswales, mobile furniture, and open-air stages, thereby transforming the area into a versatile space suitable for concerts, artisan markets, educational events, and impromptu gatherings. The architectural expression remained subtle and context-aware, as evidenced by the incorporation of wooden pergolas, local stone paving, and a muted color palette that harmonized with the surrounding vegetation. The outcome of this initiative is a civic platform in which culture, ecology, and climate resilience converge.

Source: Website Link

The Challenges Associated with Design, Construction, and Cultural Integration

The transformation of the Great Plaza was not without challenges. One major issue was reconciling divergent expectations among stakeholders, including garden administrators, city planners, environmentalists, and local residents.

Achieving equilibrium between technical performance (e.g., drainage and shading), aesthetic quality, and programmatic flexibility required meticulous design iteration. The design team was also constrained by existing trees and infrastructure, prompting modifications to excavation plans and layouts to preserve root zones and protect heritage species.

Construction logistics posed further difficulties. Given the garden’s status as a protected site and tourist destination, work proceeded in phased segments with limited machinery access and strict environmental controls. Budget constraints required locally sourced, cost-effective materials, with priority given to high-impact interventions.

The project demanded a nuanced approach to appeal to both garden-goers and the broader urban public. To ensure the plaza served more than a decorative gateway, a thoughtful programming strategy and strong community engagement were essential. The goal was to transform the plaza into a social commons for Medellín.

The Integration of Climate-Responsive Architecture and Landscape Design

The design incorporates low-tech, nature-based solutions to address the increasing heat and heavy rainfall events affecting Medellín. Rather than relying on mechanical systems, the plaza employs passive cooling methods, such as:

The extent of tree cover, as measured by canopy cover, is a critical ecological indicator.

Vine-covered pergolas are a type of outdoor structure characterized by their use of vines to cover the pergola’s frame, contributing to a natural and aesthetic appeal.

The concept of strategic airflow corridors is a critical aspect of air traffic management, facilitating the efficient and safe movement of aircraft through designated routes.

Water-sensitive urban design (WSUD) strategies encompass the implementation of permeable pavements as a key component of the infrastructure project, bioswales and retention gardens, and utilization of subsurface water storage systems as a strategic measure employed to mitigate the risk of flash flooding. These systems operate discreetly within the architectural language of the site. The integration of these elements exemplifies the potential of public space architecture to contribute meaningfully to urban climate adaptation, thereby enhancing environmental comfort without compromising usability or aesthetics.

Designing for Culture, Gathering, and Everyday Use

The transformation of the Great Plaza has reconceptualized it as an urban living room—a space that is not merely traversed, but inhabited, performed in, and participated in. The transformation of an unadorned, exposed forecourt into a vibrant space for the city’s collective life is a noteworthy development. The redesign places a premium on social flexibility, allowing the plaza to serve as a venue for a wide array of events, ranging from casual social gatherings and educational programs to large-scale cultural events such as concerts, artisan fairs, and traditional storytelling gatherings.

The revitalization was driven by a community-centered design process, shaped through extensive co-design workshops involving residents, artists, garden staff, and cultural organizations. These participants exerted a direct influence on the plaza’s spatial configuration, encompassing elements such as shaded seating, performance areas, and quiet zones. The design also drew on local materials and Andean vernacular textures to embed cultural memory and reinforce regional identity. This approach engendered a sense of communal ownership, thereby anchoring the plaza within Medellín’s overarching vision of public space as a catalyst for civic reconstruction and quotidian cultural expression.

The Concept of Ecological Awareness within the Context of an Urban Environment.

Despite its location at the entrance to a botanical garden, the new plaza does not serve as a decorative extension of curated flora. Instead, it functions as a living ecological infrastructure—a space where urban life and natural systems are intricately intertwined. This integration is indicative of a more extensive transformation in Medellín’s urbanism, wherein green infrastructure is no longer relegated to parks or peripheral areas, but rather, it assumes a pivotal role in the design of civic spaces.

The Great Plaza has been redesigned to integrate native and adaptive plant species, with the objective of enhancing ecological resilience while supporting human activity. Trees provide shade, while pollinator-friendly shrubs and rain gardens enhance biodiversity and manage stormwater. These green infrastructure elements are seamlessly integrated into the plaza’s layout, coexisting with seating, pathways, and gathering areas. This integration ensures that environmental performance complements, rather than hinders, public use. This holistic approach reflects a new paradigm in urban design, where ecological function, sustainability, and cultural life are deeply interconnected and mutually reinforcing.

Implications for Urban Public Realm Design

Medellín’s Great Plaza redesign represents more than a localized improvement; it serves as a scalable model for urban resilience across the Global South. The project demonstrates the potential for environmental sustainability and cultural relevance to coexist and enrich one another, particularly in addressing intertwined challenges such as climate vulnerability, cultural erosion, and public space underuse. By conceptualizing architecture and landscape design as instruments for civic revitalization, the plaza serves as a unifying space, mitigating social disparities and fostering a renewed sense of communal belonging. The strength of this initiative lies not only in its physical upgrades but also in its social responsiveness, achieved through participatory, community-driven design. Of note, the project eschews ostentation in favor of modest, integrated climate solutions—such as bioswales, shade structures, and permeable paving—embedded into daily practices. Cultural expression materializes through local materials and spatial storytelling, avoiding grand gestures. This subtlety gives rise to a public space that exudes authenticity, inclusivity, and connection to its locale. The Great Plaza embodies a novel paradigm for 21st-century urban design, situating ecological intelligence and cultural depth at its core. It serves as a compelling reference point for cities seeking to construct resilient, human-centered public spaces.

The 2022 redesign of Medellín’s Great Plaza offers a compelling example of how architecture and landscape can respond to the intertwined challenges of climate change and cultural fragmentation. Instead of merely beautifying the space, the project transforms the plaza into an active agent in civic life. This agent fosters ecological function, cultural expression, and prioritizes everyday usability. The incorporation of local materials, communal design processes, and passive climate strategies exemplifies a profoundly contextual and community-centric approach.

The transformation of the plaza serves as a testament to the indispensability of public space, particularly in urban centers grappling with environmental and social challenges. This finding underscores the notion that climate adaptation can be achieved without compromising cultural authenticity, and that small-scale, grounded interventions can generate substantial urban impact. As cities across the Global South seek models for inclusive and resilient development, the Great Plaza offers a timely and tangible reference. This project underscores the notion that meticulous design, guided by ecological intelligence and cultural memory, can facilitate reconnection, cultivate resilience, and reimagine the potential of the urban public sphere.

- Botanical Garden of Medellín. (2023). Joaquín Antonio Uribe Botanical Garden official website. https://botanicomedellin.org/en

- Medellín City Planning Department. (2022). Medellín green infrastructure and public space strategy. Medellín City Council. https://medellin.gov.co/green-strategy

- Ospina, D., & García, L. (2023). Participatory design and urban renewal in Medellín: Case studies on public space transformation. Journal of Urban Regeneration and Renewal, 16(2), 142–158.

- Pérez, M., & Rodríguez, A. (2022). Climate-responsive urban design in Latin America: The case of Medellín’s Great Plaza. Sustainable Cities and Society, 75, 103322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.103322

- Velásquez, J. (2022). The integration of bioswales and permeable paving in Medellín’s urban public spaces. Landscape and Urban Planning Review, 12(1), 50–62.

- Vélez, A. E., & Castro, L. (2006). Jardín Botánico de Medellín: Informe de diseño y planificación [Design and planning report]. Landscape as Urbanism Americas. https://landscapeasurbanismamericas.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/AnaElviraVelezLorenzoCastro_JardinBotanicoMedellin_2006.pdf

- PlanB Arquitectos. (2006). Orquideorama: Proyecto para el Jardín Botánico de Medellín [Orquideorama project for the Botanical Garden of Medellín]. Landscape as Urbanism Americas. https://landscapeasurbanismamericas.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/PlanB_Orquideorama_2006.pdf

Seakmy Ty

Seakmy Ty is a Cambodian architecture student pursuing a master’s degree in urban planning in France. Originally from Phnom Penh, a city that is rapidly changing due to urban growth, she has developed a deep passion for sustainable urban design and planning. She has received academic training in smart city systems, energy efficiency, and resilience strategies. Seakmy is particularly interested in how design and governance can create cities that balance rapid development with long-term environmental and social well-being.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

Kim Dovey: Leading Theories on Informal Cities and Urban Assemblage

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “