Post-Conflict Urban Masterplans Transforming the Global South

This article explores how post-conflict urban masterplans are transforming cities across the Global South by serving as tools for reconstruction, reconciliation, and state-building. Through an examination of Kigali, Rwanda and Medellín, Colombia, it highlights how urban planning is being deployed not only to repair physical infrastructure but also to reshape national narratives and project modernity in the aftermath of violence. The paper considers the influence of transnational planning models, including the rise of green growth, leapfrog development, and culture-centred frameworks like UNESCO and the World Bank’s ‘CURE’ approach. It argues that masterplans in post-conflict contexts function as powerful instruments of statecraft, rebranding cities and securing international legitimacy while also raising critical questions about inclusion, displacement, and the politics of spatial transformation. Ultimately, the article positions post-conflict urban planning as a multifaceted and strategic response to crisis that merges local recovery with global urban development agendas.

Spatial Repair and Social Healing in Post-Conflict Urbanism

Post-conflict urban masterplans prioritize rebuilding cities through addressing the unique challenges and opportunities faced by a society emerging from a period of conflict. These plans often seek to generate inclusive, resilient and sustainable urban environments that have the capability to reconcile, foster social cohesion and promote economic recovery, thereby allowing for collective social healing. Urban reconstruction in post-conflict settings needs to be spatially coherent, thoroughly inclusive of the different social groups and vulnerable populations, and attentive to cultural heritage. Whilst new masterplans present a policy challenge that can either exacerbate or help alleviate simmering tensions, urban planning in the face of conflict is an instrument by which economies and societies can be rebuilt.

Following a period of conflict, architecture and urban redevelopment have become a key political instrument in achieving new policy goals and building peace. The redesigning of the built environment can equally serve to repair infrastructure and the social fabric of the city through its ability to recreate social relationships, associations and civic engagement while expressing the different memories and sites of contestation that may exist.

Masterplanning Cities: a Catalyst for Development

In the global south, masterplanned cities look to emphasize technological progress and leapfrog urbanization as a pathway towards accelerated modernity and in cases where conflict has occurred, urban masterplans offer a ‘clean slate’ beginning towards reshaping physical and social structures. Post-conflict urban transformation allows for government regimes to move away from the negative narratives of state failure, conflict, and economic turmoil. Instead, new masterplans present fresh and exciting new plans that give the country a new and legitimate direction within which the state’s own transition can take place by providing novel ways to reconfigure local space.

The promise of leapfrog development is a theoretical ‘win-win’ solution to immediate economic growth that promotes national transformation and brings countries recovering from eras of conflict a fast-tracked route to development and catching up with the already industrialized global north.

Another reason urban masterplans are transforming countries in the global south recovering from conflict is due to the concerns and anxieties from governmental regimes surrounding continued mass urbanization. The constant growth and expansion of existing cities sees current infrastructure failing to support the demand. Over-crowding in urban environments exacerbates social issues such as poverty, which only becomes worsened in times following conflict.

Source: Website Link

Deciding how to move forward: the importance of culture in urban transformations

Recently developed by UNESCO and the World Bank in a joint effort to aid countries recovering from conflict, the CURE (culture in city reconstruction and recovery) framework places culture firmly at the centre of planning efforts. The culture-based approach seeks to aid city reconstruction and recovery through directly accounting for the needs, values, and priorities of the people most affected by the violence that has taken place. CURE argues that culture is mainstreamed into all sectors of how citizens interact with their urban environments. Therefore, integrating culture into new masterplan efforts will strengthen a community’s sense of belonging, supporting the healing process and necessary reconciliation.

As seen in the following case studies, this can be achieved through the reconstruction of culturally significant landmarks, monuments, and publicly significant areas. UNESCO and the World Bank argue that acknowledging the framework’s four phases (1. Damage and needs assessment; 2. Policy and strategy; 3. Financing; 4. Implementation) as the foundation that integrates people and place-based policies, then states will better achieve urban transformation that addresses key areas of contest, creating a better city experience for the people that inhabit it.

A Case Study Review: Kigali, Rwanda (Post-Genocide 1994)

The Kigali City masterplan, released in 2008 (later revised in 2013 and 2020), prioritizes national reconciliation and economic growth. Following the conflict, urban transformation, state rebuilding and ecological modernization (a strategy whereby economic growth and environmental protection are compatible and mutually beneficial for overall development) were identified as the key processes necessary to Rwanda’s ongoing national transition.

Beginning in 2013, the masterplan seeks to reshape the city of Kigali until 2040 through zoning plans, the demolition of informal modes of inhabiting the city, and the promotion of green aesthetic renewal. This entails developing a structured zoning system to include residential, commercial and industrial developments, an emphasis on creating accessible green spaces, as well as developing public infrastructure through roads, transit and other services. In the case of Rwanda, a new masterplan design with a focus on creating a green, ecologically advanced city, offers an urban fix to the post-genocide national transformation that is required to mark a ‘clean’ break from the country’s violent past.

A Case Study Review: Medellín, Colombia (Post-Cartel Era)

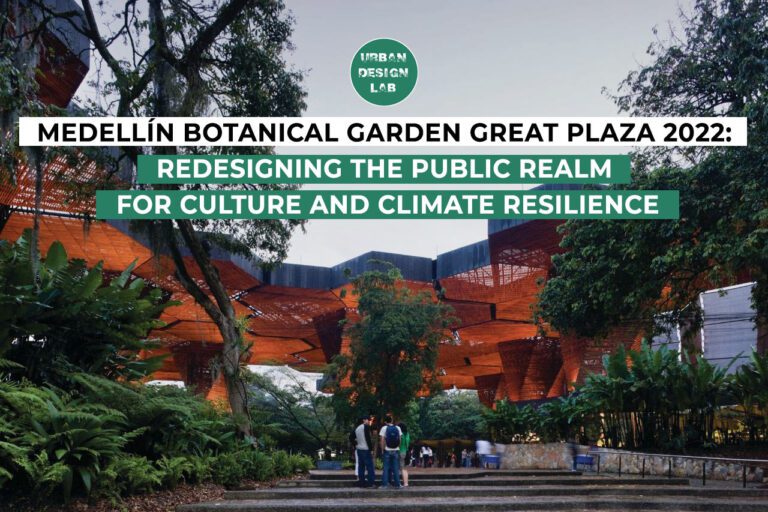

Plagued by cartel violence, the early 2000s urban transformation plan was designed to move the city in a new direction towards becoming a vibrant new hub of innovation and culture, with urban resilience at its centre. The plan focuses on social urbanism, using development to directly address existing inequalities and violence. Using infrastructure, urban design and architecture, the masterplan would redefine mobility and public space as key instruments to achieving progressive policy agendas.

The masterplan includes developing public transport networks, such as cable cars and a metro system, thereby connecting marginalized neighbourhoods to the city centre, recreating public spaces and libraries through the development of cultural centres in areas previously controlled by armed groups, thus fostering an element of community engagement and providing alternative spaces for recreation and learning. Critically, the masterplan also works to revitalize neglected areas, once heavily influenced by cartel control, by improving living conditions and promoting economic opportunities.

Transforming Medellin, the masterplan has contributed to a reduction in homicide rates and an improved quality of life for residents, including safety and security, as well as fostered a sense of community, empowering citizens to participate in the city’s transformation.

Transnational Models that Reflect the Global Circulation of Planning Ideals

Geographically located in distinctly different parts of the world, both Kigali and Medellin serve as models for other cities in the global south recovering from periods of conflict, demonstrating the potential of urban planning and design to address social issues. Teams of architects, social workers, planners, communicators and engineers on each of these projects have collaborated with government actors and communities to identify and map local requirements and redevelop public spaces and infrastructure to support and foster wellbeing, connection and community. In the case of Rwanda, the urban vision borrows heavily from East Asian development models utilized in highly developed locations, such as Singapore, where proven models are emulated through the circulation of policy within the global community via consultants, architectural corporations and state elites.

Theoretical concepts such as leapfrog development, the eco-city and smart city narratives are used to reposition nations and their urban spaces within futuristic and globally competitive urban discourse. New masterplans that are incorporated following periods of conflict are therefore not only environmental or for the immediate good of local users, but are also deeply political and economic, serving to rebrand the nation, thereby attracting international development and finance.

Urban Masterplans as a Tool of Statecraft

Urban transformation within the global south is therefore deeply tied to state rebuilding and in the case of Rwanda, political legitimation through reaffirming a relationship between state actors and citizens. The Kigali masterplan offers a tool for projecting modernity, unity, and state capacity in the wake of national trauma. In both instances (Kigali and Medellin), urban masterplans following eras of conflict are a symbolic signal that the country has come to a sense of reconciliation and moved beyond the crisis. Post-conflict urban transformations provide justification for national intervention in urban spaces and can be used to procure international funding, demonstrating a legitimate need for support in development.

Conclusion

Post-conflict masterplans are fundamentally reshaping the urban trajectory of the Global South, offering not only physical reconstruction but a strategic reconfiguration of national and urban identity. In cities like Kigali and Medellín, masterplans have become instruments for governments to reposition themselves, signalling stability, modernity, and readiness to reengage with the global economy. These plans serve as a reset, allowing nations to distance themselves from narratives of violence and failure by projecting visions of green growth, technological innovation, and inclusive development. They also reflect the increasing influence of transnational planning models, such as eco-city frameworks and the CURE approach, that blend global ideals with local cultural recovery. While challenges around exclusion and displacement remain, post-conflict masterplanning is emerging as a critical tool in transforming the Global South—aligning physical reconstruction with state-building, international legitimacy, and a reimagined urban future.

References

- Alvarez, V. R. (2024). The Urban Transformation of Medellín: A Case Study. ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily.com/1015216/the-urban-transformation-of-medellin-a-case-study

- Harboe, L., & and Hoelscher, K. (2023). Architecture, politics and peacebuilding in Medellín. Peacebuilding, 11(4), 403–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/21647259.2023.2211835

- Hudani, S. E. (2020). The Green Masterplan: Crisis, State Transition and Urban Transformation in Post-Genocide Rwanda. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 44(4), 673–690. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12910

- Hudani, S. E. (2020). The Green Masterplan: Crisis, State Transition and Urban Transformation in Post-Genocide Rwanda. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 44(4), 673–690. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12910

- UNESCO, World Bank (2018) City in Reconstruction and Recovery: Position Paper https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000265981#:~:text=Year%20of%20publication,2018

Frederick Bottrill

About the Author

Frederick is a recent graduate from McGill University, where his academic focus was on Urban Studies and International Development. His independent research projects included exploring New Master Planned Cities and Smart City initiatives. Freddie also has experience working on urban development projects at the Norman Foster Foundation and at present is an Architectural Research intern at the Urban Design Lab.

Related articles

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “