Reviving Heritage: Kuching Waterfront

- One Comment

- 26. Mixed-Use Environment, BOJANA PALIFROVSKA, Climate Resilience, Community Transformation, Downtown Kuching, Environmental sustainability, Gentrification, Heritage Preservation, Infrastructure Modernization, Pedestrian Bridge, Sarawak River, Social Equity, Tourist Attraction, urban regeneration, Waterfront Development

Kuching, the capital of Sarawak, has long been an urban stronghold where cultural identity and social heritage meet the contemporary needs of the modern man. Its historical narrative is deeply intertwined around the course of the Sarawak River, which has been a tireless witness and participant in the city’s evolution from ancient times to the present day. Kuching’s War Quay, once a bustling commercial hub and later a neglected riverfront, has undergone a remarkable transformation.

The ambitious goal behind the project was to restore the coastline to its former glory and inject a new urban vibrancy that resonates with locals and visitors alike. This case study aims to offer answers around the project and delves into the meticulous planning and design that brought this key piece of the puzzle called Kuching to life.

Historical background

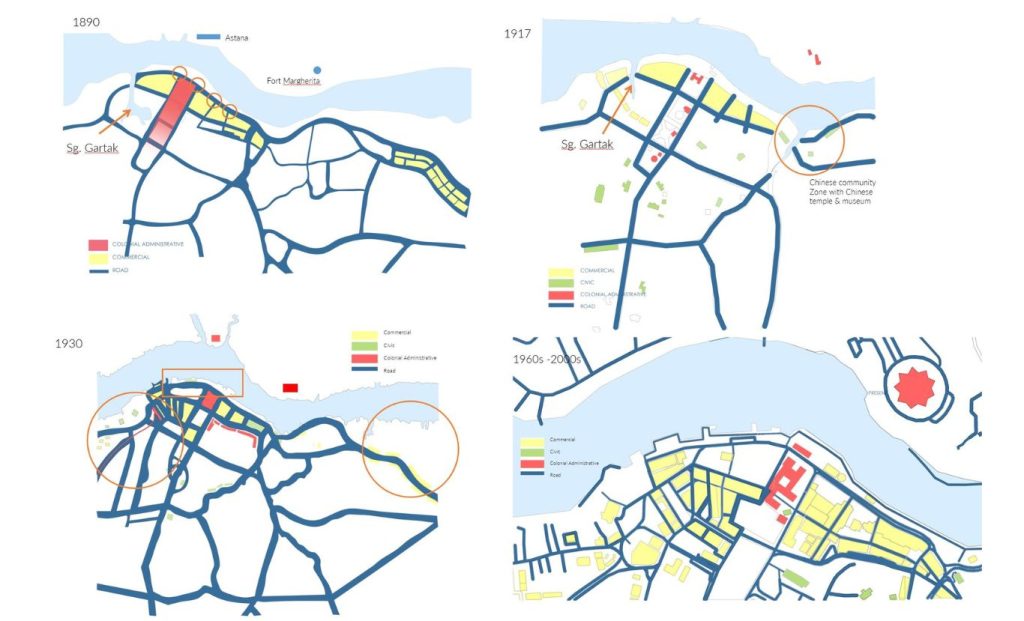

Kuching, the capital of Sarawak, an area then part of the British colonial state from 1839 to 1963, became independent in 1963 and joined the territory of Malaysia. The state’s economy has long relied on foreign trade, with Kuching, its capital, playing a key role as the primary sea and air link. The city’s early development (Wahid, 1985), was closely linked to its coast, where ports such as Ban Hok and Loma Don greatly facilitated international trade, shaping the physical and economic landscape of the downtown area.

While the main international transport facilities have since moved to Tartah Puteh, the ports in the center of Kuching remain an integral part of local trade. Despite the changing economic climate, the city center remained largely unchanged from 1963 to 1987, with development occurring primarily on its outskirts.

Evolution of Downtown Kuching

The Kuching Waterfront Project is more than just an urban renewal initiative; it’s a tribute to the city’s rich history. Coastal restoration was not only about physical structures, but also about reviving a historical narrative that had faded over time. Architects and planners faced the challenge of preserving the essence of Kuching’s past while working for a space that meets the demands of modern urban life.

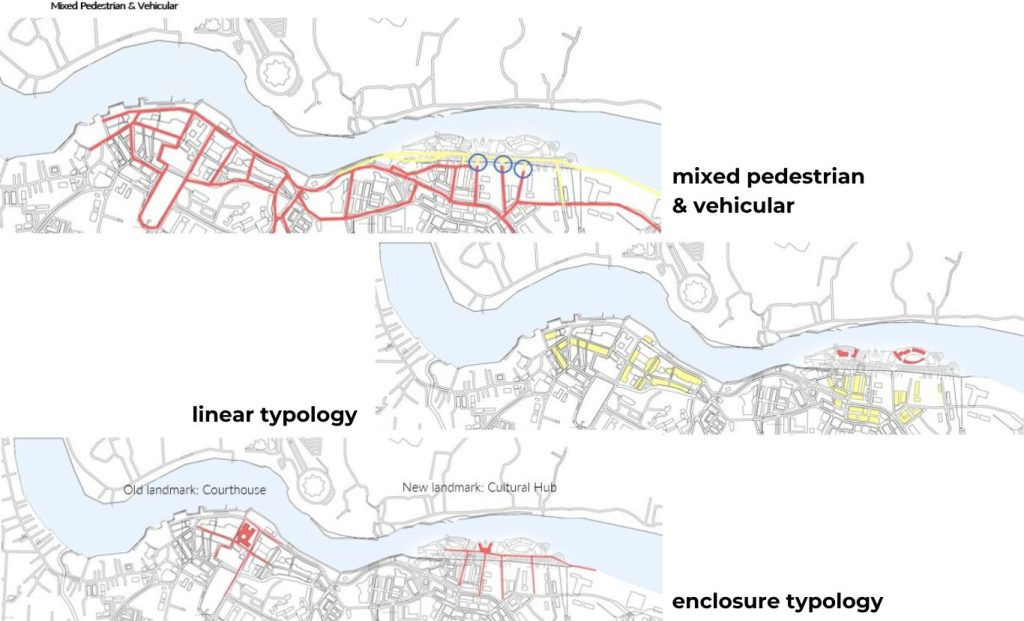

The central urban area of Kuching, originally centered on the riverbank, has gradually expanded inland in direct proportion to the growth of the city. Consequently, the coastal belt of the river, however, remains underdeveloped, preserving its potential to be incorporated into some future visions of future urban planning. Architecturally, the central business district (CBD) is experiencing little dynamic change, with buildings reflecting different historical styles but lacking a cohesive urban plan, nor unified street fronts and logic.

Hence, over the next few decades, downtown Kuching will experience slow development, with new developments often dependent on land availability rather than overall urban land planning. The architectural character of the area has remained largely intact, with shops and small blocks creating a friendly environment suitable for walking and cycling.

Source: Website Link

A Need for Design that Respects and Reimagines

The city of Kuching, as a commercial, cultural, and administrative center, as a result of the economic expansion, faces an increasing need for recreational spaces and the need for quality living spaces. While the city is experiencing investment expansion, its physical environment begins to degrade (becoming a stronghold of social injustice, lack of green spaces, and reduced land values) due to a lack of coordinating policies for urban development. Left without major infrastructural and urban intervention, downtown Kuching risks further deterioration, despite its historical and cultural significance.

The physical expansion of the city is primarily taking place in new townships such as Petrajaya and East Kuching, driven primarily by political pressure, but also by the availability of state-owned land. While these areas have seen rapid development, the city center has been abandoned and neglected, and its visual and physical connection to the Sarawak River is more a symbol of diversity than a physical connection to overcome it.

The Historical Importance of the Sarawak Riverfront

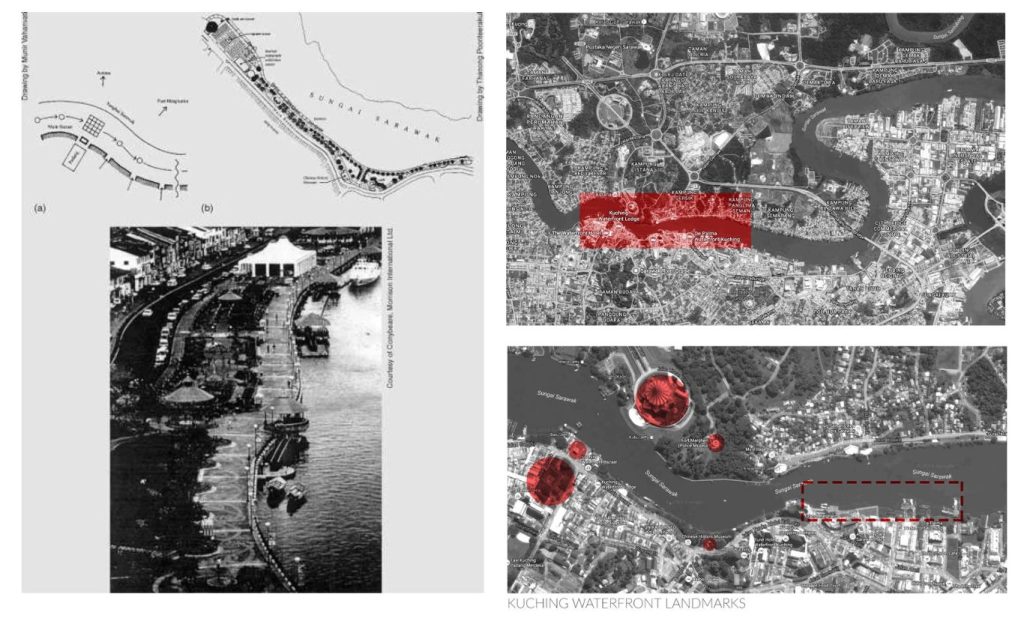

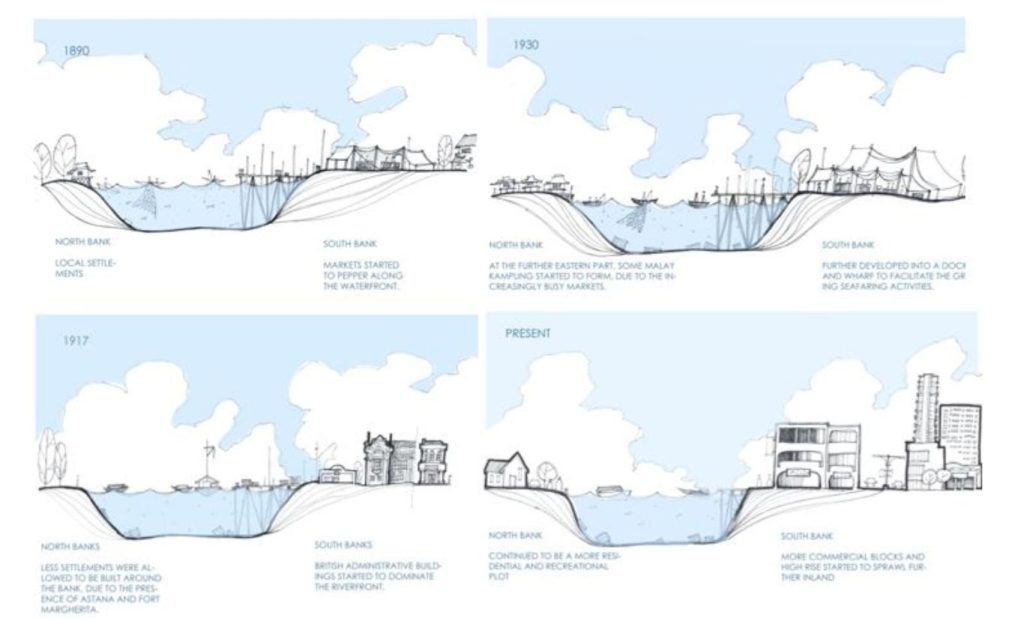

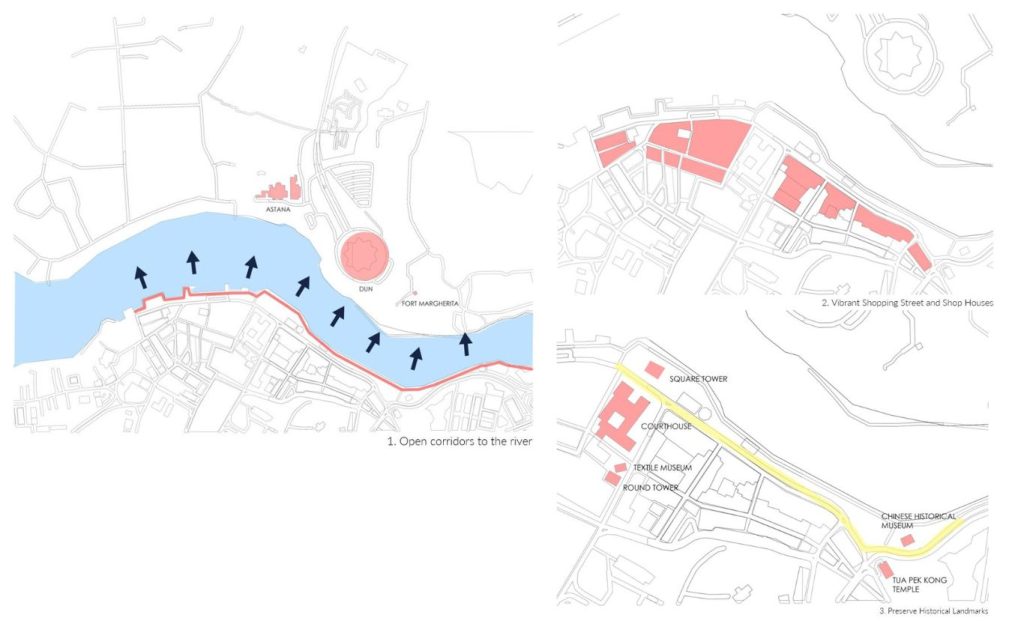

The Sarawak River has often historically served as a stronghold of political governance and a symbol of power, which would significantly influence the location of the city’s early development. The communication nodes formed at the key intersections along the river bank, framing views of important landmarks such as Astana and Fort Margherita, speak for this fact in particular. Over time, with the construction of docks and ports along the coast, expansions are observed, which will often signal the growth of maritime traffic.

As the city expanded inland, the dependence and need for the river decreased, which led to the initiative to introduce pedestrian corridors along the coast in order to reactivate the public space of this part of the city. The historical importance of the riverfront was recognized in the city’s strategic planning documents initiated in 1989, with the aim of creating a vibrant public space that reflects Kuching’s cultural heritage and identity.

The Major Urban Improvement (1989)

The first realization of an urban undertaking takes place in 1989, led by United Consultant (Kuching) & Conybeare Morrison & Partners, which focuses on the transformation of the river bank, turning public space accessible to all users . According to (Tirkey, n.d.), the project emphasized several segments such as:

- creation of an active shopping street for small businesses,

- preservation and affirmation of the historical landmarks and customs of Kuching and

- improving the passability in the central city area and increasing the pedestrian infrastructure along the coast.

Key aspects include connecting the main shopping artery to the water, realizing mixed-use developments appealing to both locals and tourists, and preserving the historic elements that define Kuching’s character. The project successfully revitalized the urban area, creating a continuous corridor of public space along the waterfront that became a model for similar developments in Southeast Asia.

New Kuching waterfront extension project (2013)

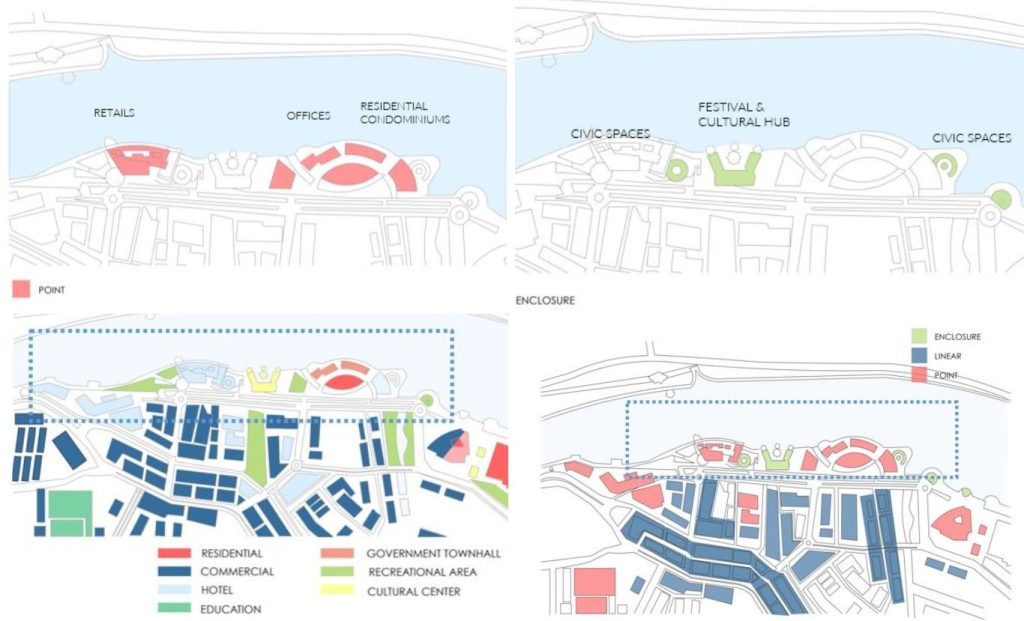

Continuity for the expansion of landscaped urban land is also visible in the project launched in 2013 as a investment between IBRACO and Pelita Holdings. This realization aims to further contribute to the restoration of the coast by incorporating various functions (economic, entertainment, tourism, and social). The project introduced several new elements, including an open-air plaza, commercial spaces, exclusive residential developments on the waterfront, and improved connectivity with the rest of the city’s urban morphology.

The project team (Ibraco, n.d.) recognized the need to reconcile the cultural significance of the coast with its natural surroundings. The Sarawak River, was treated not only as a backdrop but also as an integral part of the design. Green spaces were introduced along the coast, offering areas for relaxation while maintaining an ecological balance. These spaces also serve as venues for cultural events, further embedding the project in the cultural tissue of the local community.

The construction used advanced engineering techniques to stabilize the aging shore walls, ensuring that they could withstand the expectations of the planned span. Additionally, the introduction of sustainable drainage systems was a sign of both innovation and environmental responsibility, addressing potential flooding issues while preserving the site’s aesthetic appeal.

The River Linking and Revitalization of the Sarawak Riverfront

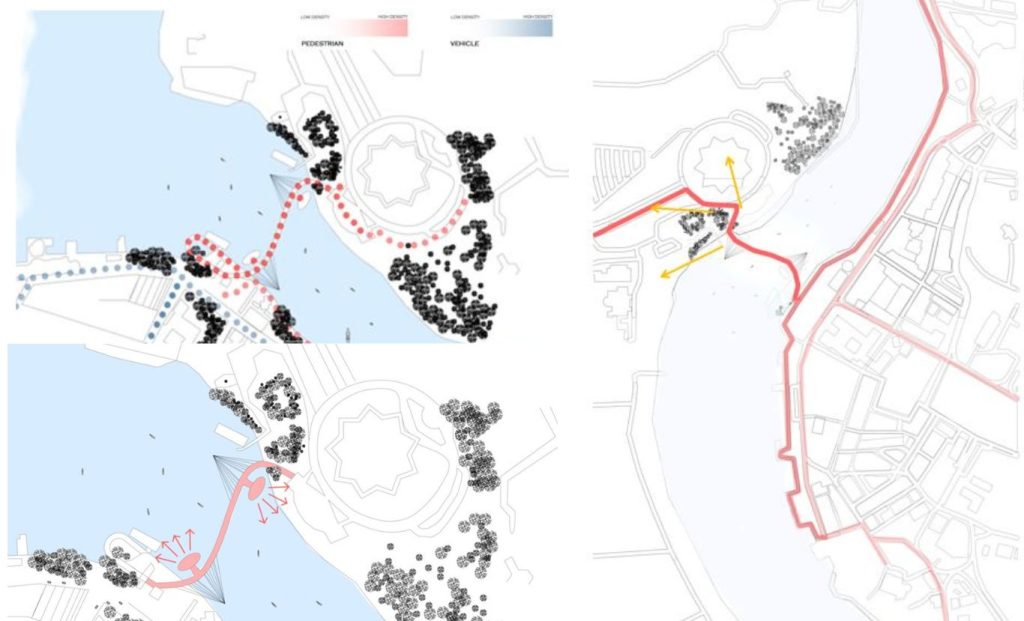

The Golden Pedestrian Bridge, was introduced as a key element of the waterfront extension, connecting the north and south banks of the river. This bridge not only improves connectivity but also aims to harmonize the urban density between the Malay Kampung neighborhoods on the north coast and the bustling commercial areas on the south coast.

By providing an alternative route for pedestrians, the bridge helps alleviate traffic congestion at Tun Salehuddin Bridge and Jalan Gambier, improving the walkability and accessibility of this stretch.

The waterfront revitalization strategy (“Kuching Waterfront Development Projects,” 2023), focuses on creating a mixed-function environment that encompasses a variety of day and night activities. By integrating residential, commercial, cultural, and recreational functions, the waterfront is day by day becoming a hub of activity, encouraging constant human interaction and socialization, reducing the risk of dead unsafe zones and creating voids in Kuching.

The urban plan includes new pedestrian and bicycle paths that serve as buffer zones between public and private spaces, encouraging a gradient of urban interaction and improving connectivity, providing.

Weaving Past and Present

A key aspect of waterfront development is the preservation of Kuching’s historical heritage while integrating modern elements to meet the contemporary needs of citizens. The east bank, with its small commercial units and streetscapes, has been carefully preserved, while new functions have been integrated to complement the area’s cultural heritage.

This approach seeks to respect the authentic meaning of the urban fabric while introducing uses that increase its appeal by making it an active urban space. However, the incorporation of high-rises has raised concerns about obstructing river views and potentially privatizing public spaces.

Empowering Change: Social and Community Transformation

The revitalization of Kuching’s waterfront has had a profound impact on the local community. Once a neglected area, the waterfront is now a vibrant public space that encourages social interaction and cultural expression.

The project reconnected Kuching residents with their river (“Retrospective: Kuching Waterfront,” n.d.), with a 1.5 kilometre promenade, parks, playgrounds, grand water steps, entertainment centres, food stalls, museum, many public artworks and a tourist centre, transforming the waterfront in a continuous ribbon and a communal gathering place that celebrates the city’s diversity. The economic benefits have also been significant, with the waterfront attracting tourists (Chin et al., 2020) and boosting local businesses, contributing to Kuching’s wider urban regeneration efforts.

Between Criticism, Cultural Preservation and Social Equity

Conclusion

Kuching’s waterfront expansion project (“Kuching Waterfront Development Projects,” 2023), meanwhile, has been criticized for its potential to increase land values, and suspicions that it could help reduce crime and unemployment rates. The project is also seen as prioritizing commercial interests over the needs of the local community, leading to the displacement of long-standing markets and disruption of natural resources.

While waterfront development has brought new life to Kuching, it has also highlighted the challenges of balancing economic growth with cultural preservation and social equity. Moving forward, the transformation of Kuching’s waterfront will always stand as a testament to the power of thoughtful, culturally sensitive urban design.

The project successfully melds the old with the new, creating a space that honors Kuching’s rich history while providing a dynamic environment for contemporary urban life. As a model for future urban regeneration projects, Kuching Waterfront shows that, is possible to breathe new life into historic areas, ensuring they continue to play a vital role in the city’s narrative for generations to come.

References

- Berhad, I. (n.d.). Kuching water front current project. ibraco. https://ibraco9.wixsite.com/ibraco/kuching-water-front-current-project

- Chin, Y., Lo, M., Mohamad, A. A., & Ha, S. (2020). Factors influencing the destination image of Kuching waterfront: A tourist perspective. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.10.54

- Juien, L. University Teknologi Mara. (2021). Kuching Waterfront Development Impact on Urban Tourism [Master’s thesis]. https://ir.uitm.edu.my/id/eprint/51986/1/51986.pdf

- Kuching waterfront development projects to enhance tourism activities. (2023, August 8). New Sarawak Tribune. https://www.newsarawaktribune.com.my/kuching-waterfront-development-projects-to-enhance-tourism-activities/

- Kuching waterfront. (2020, June 15). Visit Sarawak 2022 #BounceBackBetter. https://chinese.sarawaktourism.com/attraction/kuching-waterfront/

- One moment, please... (n.d.). One moment, please… https://kunlim.com/kuching-waterfront-city-kuching-sarawak-malaysia/

- Retrospective: Kuching waterfront. (n.d.). CM+ Conybeare Morrison – CM+ Conybeare Morrison | Architecture, Infrastructure and Urban Design. https://cmplus.com.au/restrospective-kuching-waterfront/

- Tirkey, R. (n.d.). Rohit.tirkey.(BARCH1000916). Scribd. https://www.scribd.com/presentation/457121557/rohit-tirkey-BARCH1000916

- Wahid, J. (1985). The Physical Redevelopment of Kuching Downtown, Malaysia: An Urban Design Approach [Master’s thesis]. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/33361453.pdf

- Yassin, A. M. (2010). An evolution of waterfront development in Malaysia.

BOJANA PALIFROVSKA

About the author

An innovative urban planner with six years of experience, dedicated to sustainable communities. Holding a Master’s in Architecture, she explores hybridity in spatial formation and new museology. As a specialist, she excels in policy analysis and community development. An urban activist and writer for Porta 3, she raises awareness of social issues in urban planning. As founder of Esquina Urbana, she merges environmental psychology and planning, advocating for enhanced urban mobility and endless bike lanes.

- Articles

- 26. Mixed-Use Environment, BOJANA PALIFROVSKA, Climate Resilience, Community Transformation, Downtown Kuching, Environmental sustainability, Gentrification, Heritage Preservation, Infrastructure Modernization, Pedestrian Bridge, Sarawak River, Social Equity, Tourist Attraction, urban regeneration, Waterfront Development

Related articles

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “

One Comment

Dear Ms. Bojana Palifrovska,

I hope this message finds you well. I recently came across your work on “Reviving Heritage: Kuching Waterfront” and was truly impressed by its innovative approach, depth of analysis, and creative execution. It’s incredibly inspiring to see such quality and dedication.

I wanted to let you know that I have sent you an email regarding “A Request For Insights Related to My Design Project”.

Please don’t hesitate to reach out if you need any additional details or clarifications. I look forward to your response at your convenience.

Thank you for your time and consideration.

Best regards,

Joanne Lim