Urban Design in Barcelona

Barcelona is the capital of the Catalonia district in Spain. It has one of the most renowned urban designs in history, and there is an intricate yet rich history behind how the city got to where it is today. The city was once confined by medieval walls, slowly suffocating the population as it grew exponentially after the Industrial Revolution. A humble engineer, Ildefons Cerdà, designed a ground-breaking expansion far ahead of that time and was underappreciated for his mastery. The iconic grid-like district Cerdà envisioned has undergone many changes as the city disregarded the priorities of his design. Cerdà dedicated his life’s work to designing a healthy city for Barcelona and sadly passed away before experiencing the gratitude of the population that came years too late. However, almost two centuries later, he is now regarded as one of the most significant urban planners of all time.

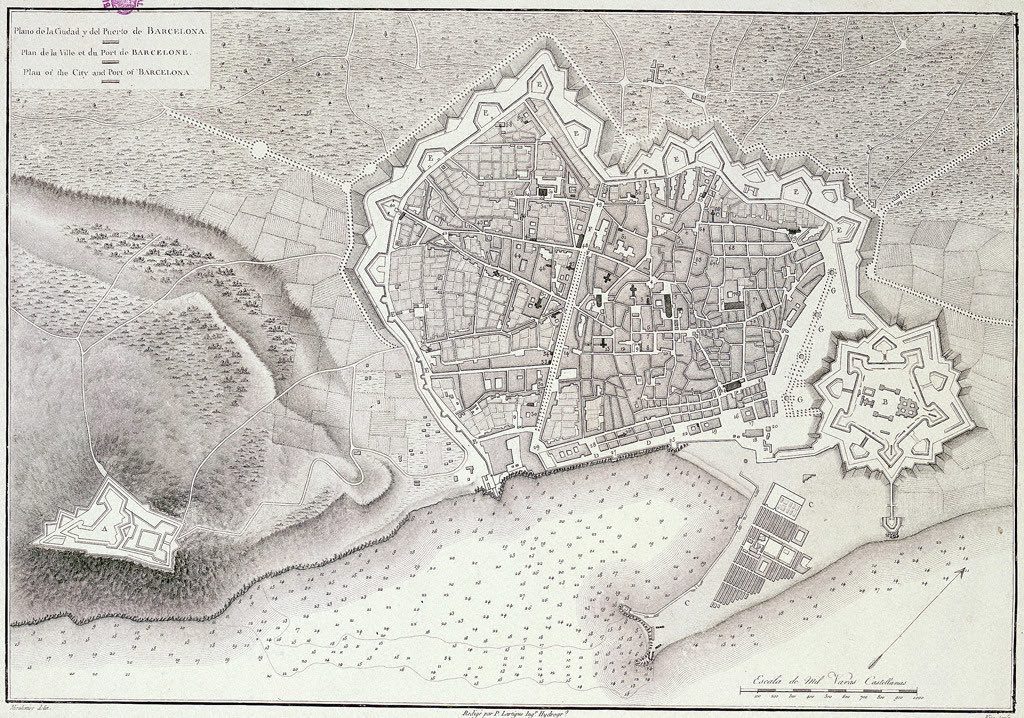

How the landscape first defined Barcelona

Barcelona is a coastal city with a unique topography. Barcelona has had a busy port since it was first built in the 15th century due to its prime connection to the Mediterranean Sea in the southeast. On either side of the municipal are two large rivers that run into the Mediterranean Sea; to the west is El Besòs and further east is El Llobregat. These rivers naturally begin to define the border of a city. Parallel to the coastline, a mountain range called Serra de Collserola borders the northwest of the city, leaving the capital to seem bound by nature on all four sides.

The collapse of the enclosed city

The industrial urban space had poisoned the population’s lives. When the textile sector rose throughout the Industrial Revolution, the city grew far ahead of the rest of Spain, including the country’s capital. In the 1850s, the population had grown to 187,000, yet these people were still confined by the medieval walls, leaving Barcelona with a density of over double that of Paris’. The walls had become a health risk and led the life expectancy to drop to 36 years for the rich and 23 years for the poor. The walled borough had become so crammed that the city could not maintain an urban hierarchy, which left the working class and Bourgeois society to coexist with the factories, slowly choking them. When the council quickly ran out of land, people grew desperate and developed ludicrous inventions to build more. Arches were erected in the middle of the street to allow houses to be built upon, and the ‘retreating façade’ technique allowed the fronts of houses to extend into the street as they rose until the parallel buildings would almost touch – entirely stripping away the circulation of the city.

Source: Website Link

The rise of Eixample

In 1854, the suffocating medieval walls were finally demolished, leaving the city desperately needing an extension plan. In 1859, the council opened a public competition for the extension, and a well-known architect, Antoni Rovira, was awarded the position where his design closely followed the lines of the old city, now known as the Gothic quarters. In an unexpected intervention, the Spanish government overruled the decision and appointed Ildefons Cerdà, which increased the political tensions between Spain’s central and Catalan administrators. The imposed nature of Cerdà’s title would forever taint his legacy. Cerdà envisioned a radical extension, which he named Eixample, where he would prioritise the population’s health in his design. The engineer did extensive research and calculations into how much atmospheric air one person would need and what professions the population might do; he even predicted the invention of automobiles. This comprehensive research led Cerdà to his iconic grid design, which we know today. Instead of Rovira’s plan, where all roads pointed to the old city, instigating a natural hierarchy, Cerdà focused on uniting the old city with seven peripheral villages which weren’t significant at the time but now comprise the city of Barcelona.

The design of Eixample

Cerdà was horrified by the conditions of living in Barcelona before the wall was demolished, especially for the working class. He ensured there would be no upper or working-class divisions in his urban plan, as he believed everyone should receive equal urban quality in their living conditions. Unfortunately, as time passed, the classes did begin to divide. The design plan Cerdà proposed as Eixample followed a strict grid layout of streets with 113-metre square-shaped blocks. The square blocks had chamfered edges, which left octagonal intersections along the grid, each evenly spread, creating the iconic uniform appearance. One of the most radical decisions in Cerdà’s plan was to include 20-metre-wide streets, a drastic change from the 1.1-metre-wide streets arranged in the old city. These old, narrow streets caused problematic traffic, and the engineer concluded that the narrower the streets were, the more deaths occurred. His research led to the conclusion that there would be some form of motor transport on the roads in the future, and therefore, his streets could meet these advances.

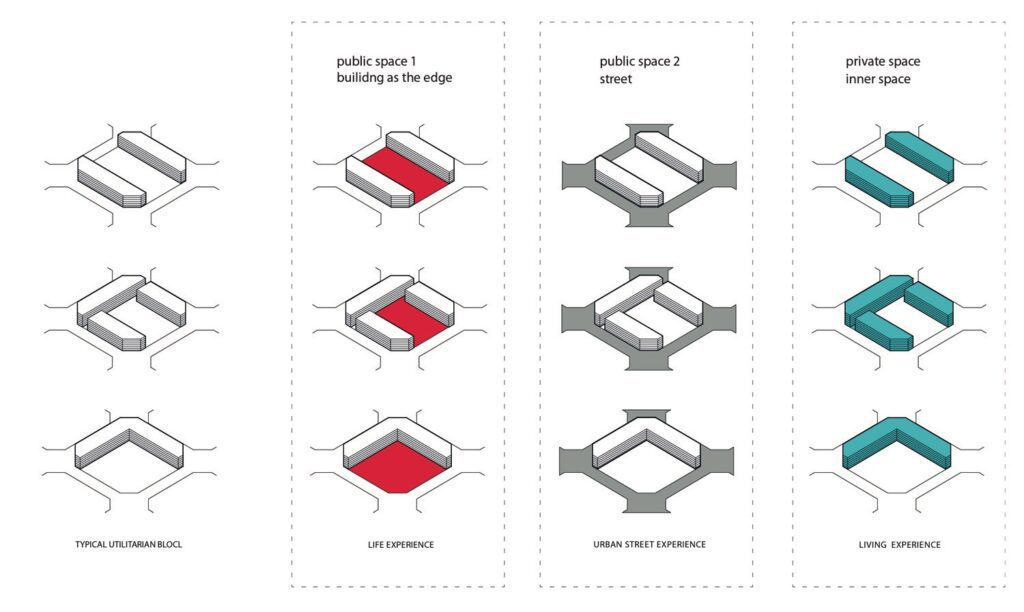

The superblocks design

Once the plan for a strict grid was established, Cerdà looked into the details of the square blocks where the buildings would be erected. His goal was to harmonise the need to build for an extension whilst allowing sufficient sunlight, air quality, green space and relaxed pedestrian mobility to ensure a healthy quality of life for people of any status. The buildings would only take up the edges of these blocks, and he implemented a rule that allowed no more than three buildings in total to leave at least one edge empty to connect to the open inner courtyards. The plan primarily presented three different prototypes of blocks: one L-shape, one with two parallel buildings, and one U-shaped with small entryways cut out of the corners. The middle of each block was intended to be left empty for green courtyards to promote a healthy lifestyle, which was of utmost importance to Cerdà. He wanted to create an urban life as rural as possible; these three types of blocks were then arranged in patterns so that the open spaces would interconnect to produce peaceful pathways through the city for the people living there.

Why does Cerdà's plan look so different?

You may be feeling confused as although we can clearly see Cerdà’s grid in modern Barcelona; it does not appear to match the details and values of his original plan. There are very few superblocks left with open courtyards full of greenery. In his original plan, Cerdà recommended a high restriction to ensure plenty of sunlight could filter into the streets and courtyards. However, the buildings were extended due to external pressures from the council and government, and height requirements were ignored. Eventually, car parks littered the centre of most blocks, and the empty edges were filled in with more buildings until the city was made up entirely of four-sided blocks where pedestrians could only move on the sidewalks. Even the street’s width was slightly reduced as no one saw its necessity and deemed Cerdà ridiculous for being willing to waste money and resources on it.

The impact of the Olympics in Barcelona

In 1992, Barcelona was chosen to hold the Summer Olympic Games, which called for a massive change in the city’s urban design. The games caused the last drastic production of the city’s urban development on the coastline, linking the Eixample to the Mediterranean Sea. The coastline was once full of derelict industrial land, and Barcelona used the investments from the games to solve a long-term problem. They demolished this dilapidated land and renovated it into a beautiful promenade with three kilometres of artificial beaches. Just inland from these beaches, they built the Olympic Village, now a residential area, and developed a sports complex around the pre-existing arena. This was monumental for Barcelona as Port Vell was overhauled and elevated into this stunning city addition, quickly attracting tourists worldwide. Shortly after the Olympics, Barcelona became one of the top tourist destinations after its successful games, and it has been a European hub for culture and tourism ever since.

Conclusion

The story behind Barcelona’s urban development stands as a testament to how we have always allowed politics to dictate our designs, ultimately ridding the value of them. Cerdà had truly pure intentions to develop a city that would benefit the population with improved health, better mobility, a more robust economy and a home they could be genuinely proud of. Although the city may not precisely look how he imagined with the most effective outcomes, Cerdà certainly did improve the quality of life in Barcelona and is now considered one of the greatest urban designers ever. Shortly before he passed away, Cerdà said, ‘Barcelona, for which in good faith I can say I have striven to do my outmost despite deep inside me the conviction that it will never know how to thank me for it’. Unfortunately, Cerdà’s vision was so ahead of time that he did not receive recognition until the Olympics came in the 1990s when Barcelona was suddenly receiving international attention for its thriving urban design. To this day, Barcelona gets the highest praise for Eixample by Cerdà as it has undeniably paved the way for urbanisation with possibly the most significant grid in design history.

References

- Bright Trip. (2024, April 5). Barcelona’s map, EXPLAINED. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q2WxxjU6lio

- Bustamante, A. V. (2023, March 17). Why does Barcelona have a perfect pattern in its street design? Medium. https://antonio-velazquez-bustamante.medium.com/why-does-barcelona-have-a-perfect-pattern-in-its-street-design-52fc121957b0

- Roberts, D. (2019, April 8). Barcelona, Spain urban planning: a remarkable history of rebirth and transformation. Vox; Vox. https://www.vox.com/energy-and-environment/2019/4/8/18266760/barcelona-spain-urban-planning-history

- Wall, F. (2020). BARCELONA´S CITY PLANNING. In YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=soJjGmRPwkQ

- Why Barcelona Looks Weird. (n.d.). Www.youtube.com. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vjb4xRywiO8

- Bausells, M. (2016, April). Story of cities #13: Barcelona’s unloved planner invents science of “urbanisation.” The Guardian; The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/apr/01/story-cities-13-eixample-barcelona-ildefons-cerda-planner-urbanisation

Holly Franks

About the Author

Holly has adored architecture since childhood. Upon completing her undergraduate degree, she found that this passion stemmed from a desire to travel and explore the vast world of architecture. Since graduating from the University of East London, she has invested all her enthusiasm into starting her architecture blog and publishing online articles.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “