Walkability in Asian Cities: The Case of Dhaka

Introduction to walkability

It is unanimously agreed by all city lovers that walkability is what makes a city good by definition. This is the one idea that is preached by most experts and researchers involved with city design. For the French writer Charles Baudelaire, walking in the city becomes a sort of a ritual, which he calls flaneur. Inspired by Baudelaire’s poetry, German Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin made this topic of flaneur a matter of scholarly interest in the 20th century, where it was considered as a representation of a typical example of an urban experience in modern society.

After World War II, walkability had become even more significant in the United States and Europe. This was due to the popularity of automobiles and the suburbanization that was occurring, alongside adaptation of the International Style of architecture. The development of suburban areas created a disconnect from people’s houses and the major business districts, which increased their reliance on motorized vehicles. As a result, most modernist planning approaches focused less on walkability. This was when American writer and activist, Jane Jacobs, became vocal about the importance of walkability in her renowned book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, published in 1961. The book is a critique of urban planning policies of the 1950s, where she denoted the first two chapters on the significant uses of the sidewalks, the public interactions ensured by sidewalks and the benefits of having safe and vibrant streets in cities. A year before Jacobs’ book was published, American urban theorist Kevin Lynch’s groundbreaking book The Image of the City also emphasized on the importance of walking.

Walkability in Asian Cities

Urban mobility in cities of the Global South such as Dhaka face numerous challenges. Although three-quarters of a Dhaka citizen’s journey comprises walking, the conditions of footpaths on the streets of Dhaka are unsafe and inconvenient, and often full of several obstructions. This makes walking rather unpleasant and oftentimes dangerous for the people of Dhaka. Architect and professor at Catholic University of America, Adnan Morshed highlighted the following reasons that make walking in Dhaka difficult:

1. Obstructions while walking

Footpaths in Dhaka lack continuity. When walking in Dhaka, you will find your way obstructed by construction materials, slopes to make way for driveways of apartment buildings, roadside hawkers, electrical poles or even a tree.

2. Pollution

Air pollution in Dhaka is notoriously bad, and the city often scores high in the list of most polluted cities in the world. In addition to the extremely dangerous levels of air pollution, the city also suffers from a prevalent situation of overall uncleanliness. Overturned trash cans, overflowing garbage trucks and open dumpsters result in an environment that is constantly reeking of bad odour. This discourages pedestrians from walking comfortably on the streets. Oftentimes, pedestrians can be seen jumping over manholes, avoiding the obstructions on footpaths, while covering their nose with a handkerchief, just to walk a few blocks in the city. All of this makes walking in Dhaka nothing less than an extreme sport.

3. Population density

The density of Dhaka is alarmingly high, and it is rising every day. On top of that, the footpaths are quite narrow. This creates a rather treacherous situation where a pedestrian has to cross that stretch of the footpath, and avoid hitting another fellow pedestrian at the same time. To make matters worse, footpaths are often occupied by electric transformers, bus ticket vendors and even police boxes, inside which policemen of Dhaka sit comfortably and watch Dhaka citizens go about their lives precariously.

4. Ambience and Reckless Driving

It is impossible to move around Dhaka without the constant fear of speeding vehicles, reckless driving of bus drivers and nauseating presence of bad odour, which is present like a constant nuisance in certain parts of the city. Such an environment makes people reluctant to walk even the shortest of distances. This is a big reason why rickshaws, a three-wheeled vehicle, function as a passenger cart for two or three people.

5. Lifestyle Choices

Buying cars is a status symbol for the middle-class population, and hence walking from place to place is considered to be a representation of a lifestyle that is somehow beneath their social status. People here aspire to purchase or at least travel by a private car, so walking is not an experience that is particularly favorable for them.

6. Women Safety

If Dhaka streets are challenging for men, it’s even worse for women who have to face the additional burden of the male gaze, along with the issues mentioned above. Adnan Morshed says the male gaze in Dhaka streets is “….a paradoxical combination of patriarchal understanding of purdah and gender insensitivity”. The city’s infrastructure is built in such a way that it only allows men to roam around freely, while the women move hesitantly, like a guest who is unwelcome at a house they are just passing through. Although women comprise a large percentage of the working population in Dhaka, they have yet to make a place of their own in the city’s public realm. It is as if the city does not belong to women, with men’s gazes constantly following their movements. As if seeing a woman out on her own is still an oddity in the 21st century, in a nation where 80% of the workers in the readymade garments industry are women.

Women also risk facing sexual harrasment when navigating the streets of Dhaka. Women make the habit of staying alert about straying hands, and can often be seen holding their bags in front of them. This serves a dual purpose – saving their belongings from pickpockets and saving themselves from being groped in public. This is a severely sorry state of affairs for nearly half of the population, who have the right to experience the city without any fear, just as any other citizen does.

7. Other Challanges

Apart from all of that mentioned above, there are numerous other challenges which arise for pedestrians in Dhaka from time to time. Monsoon in Dhaka often leads to waterlogging in the roads, due to the poor maintenance of the city’s drainage system. This makes an already perilous situation of walking in Dhaka even dangerous for pedestrians. This author once fell into the waterlogged streets, as she stepped off the footpath unsuspectingly, forgetting for a moment that the footpath height is at least one feet from the road level. Due to the flooding of the streets, the height difference of the footpath and roads is not visible to the pedestrians, which makes the streets of Dhaka nothing short of a death trap during monsoon.

Another development that is hampering the pedestrian movements in Dhaka is the construction of the Dhaka Metro Rail Project. Since February 2014, Dhaka Metro Rail, a mass rapid transit system has been under construction in Dhaka, the capital city of Bangladesh, and one of the fastest growing metropolises in the world. A new form of public transportation system is much needed in a city like Dhaka, where the density and traffic congestion both make mobility extremely challenging. However, the development of the project is causing disruptions on the city footpaths. Last year, the authorities involved with construction of the Metro Rail project observed that the train station’s entrance and exit corridors obstruct the footpaths, resulting in yet another cause of disruption of pedestrian movement. This is an alarming situation, considering that this major flaw in the design was spotted nine years after the project was initiated. This is not welcoming news for Dhaka citizens, who already face too many challenges in their daily lives due to the unsafe and unpleasant conditions of the city’s footpaths.

Bangladesh is definitely not alone in facing this crisis in creating proper infrastructure for walkability. Although traditionally, Asian cities were indeed walkable, lack of proper research and policy implementations have led to walking conditions in many Asian cities that are unsafe, inaccessible and lacking connectivity. However, the good news is that many Asian cities are trying to change this narrative. According to a research by UNEP conducted in 2017, in 83% of Asian countries, the government has made deliberate action plans (in the form of laws, policies and regulations) to achieve a beneficial outcome with regards to non-motorized transportation (NMT), which includes animal-drawn transport, cycling and walking.

Learnings from other Asian Cities

What Dhaka can do is learn from other Asian cities, and follow some basic practices and policies that can be adapted to the urban spaces in Bangladeshi context. It can be done in a number of ways:

1. Prioritizing walkability

More care is needed in allocating spaces for walking. Pedestrian movement must be given a higher level of priority when planning the infrastructure for roads. Reducing and controlling vehicle access in areas which experience high levels of pedestrian movement will lead to more vibrant and attractive spaces, which will encourage people to walk more. Vietnam has already implemented this practice in its capital Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, by allocating certain areas of the cities that remain free of vehicles on temporary and permanent basis. As a result of this, the number of pedestrians has risen, and the country’s revenue from tourism has also increased.

2. Improving Public Transportation

Good public transportation must begin and end with walking space. One of the critical problems is that we often consider walking and public transportation as two separate modes of mobility. It is imperative that when planning mobility infrastructure, the routes for walking to and from transportation hubs such as bus and train stations must also be improved with equal consideration. Proper law must be enforced regarding vehicular movements so that they don’t stop at pedestrian crossings or drive on footpaths. For instance, Kyoto in Japan had based their entire transport policy in the year 2010 on walkability, placing more emphasis on usage of public transport in order to reduce carbon emissions.

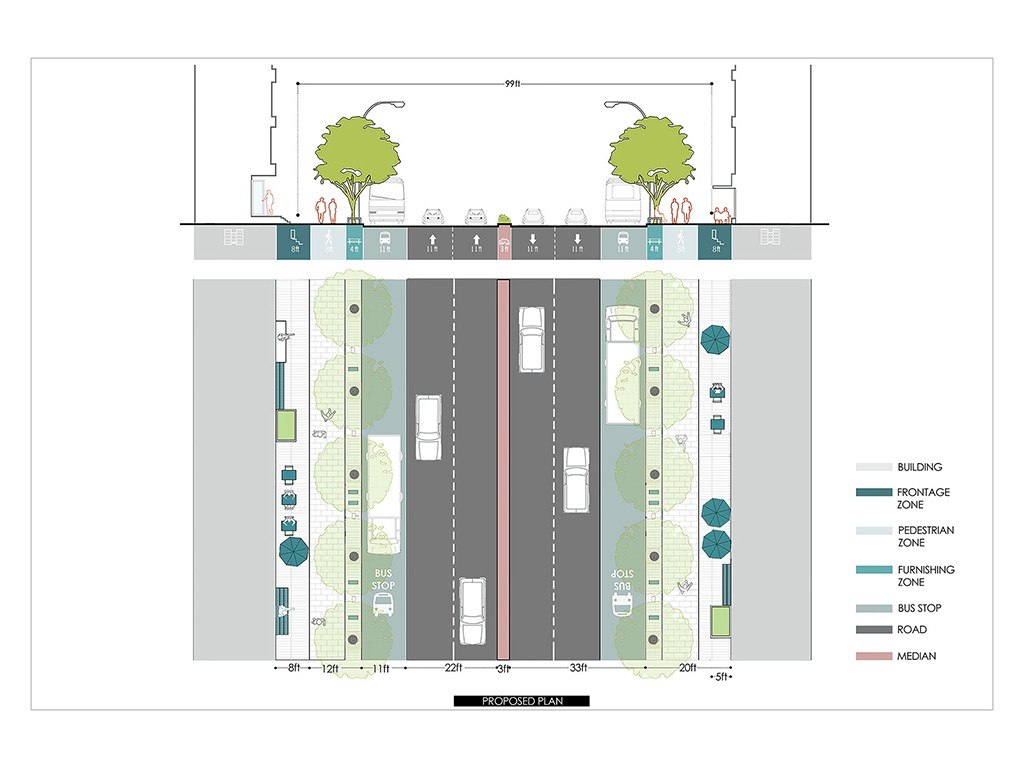

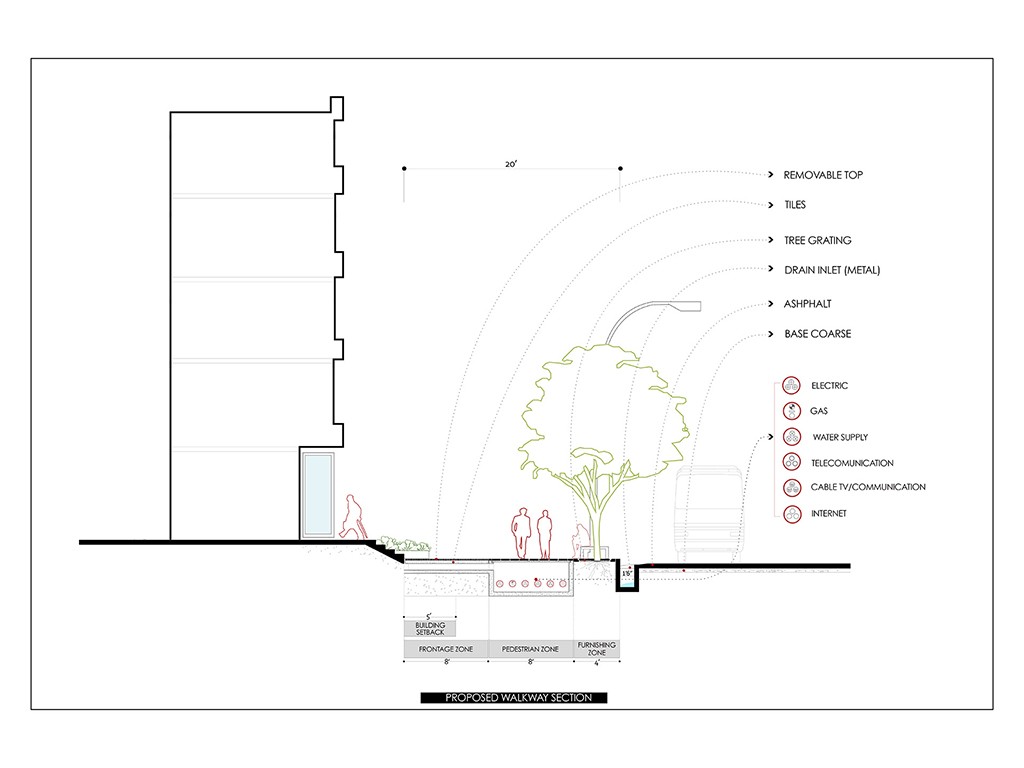

3. Street Design Guidelines

Design guidelines for walking must be prepared and implemented. Some fundamental requirements can be set in designing footpaths, such as setting a minimum width for footways of footpaths, making the footpaths at the same level as the roads, and devoid of any obstructions. Design must be made inclusive for all kinds of people, such as tactile tracks can be made for visually impaired people and gentle slopes can be provided for easy mobility of wheelchair users. In Dhaka, a research think tank named Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Dhaka prepared and published a Footpath Design Guideline which addressed and provided a guideline for these concerns.

4. Attractive and Safe Streets

At street level, some strategies can be put into motion for making walkable spaces attractive and safe. Dhaka has a tropical climate, so walking makes pedestrians sweat and become dehydrated. To prevent that, footpaths can be shaded by big trees and some seating areas can be provided for longer walkways, where pedestrians can sit and rest. The Park Connector Network in Singapore is one such example which provides these facilities.

Safety can be ensured by making walkways that are sufficiently lit, as many crimes and harassments happen to pedestrians, especially women, on dark or poorly lit footpaths.

Conclusion

As Dhaka continues to move forward with new developments, it should be ensured that pedestrians are not left behind in all of this supposed progress that is being done in the name of urbanization. Citizens of Dhaka already deal with air pollution, noise pollution, manholes without any lid, vehicles driven by reckless drivers, population density, lack of greenery and public spaces on a day to day basis. Having walkable spaces is their basic right as a citizen, and the city infrastructure should be planned and implemented to provide that.

It’s not all gloom and doom when it comes to the walking environment in Dhaka. Certain neighbourhoods like the Sher-E-Bangla Nagar and the Dhaka Cantonment have spacious footpaths that are free of any kind of obstruction and are generally well maintained. These environments make us wonder what it could have been if all of Dhaka had walking routes like that. This author’s daily commute to work would definitely be a far more pleasant experience if that were the case. The city dweller’s mental wellbeing would be vastly improved if there were good walkability conditions. It would be one less thing for the citizens to worry about in a city that is repeatedly ranked very low in terms of livability.

Walkability not only makes a city more accessible for people from all social classes, but it also contributes to improved physical and mental health, reduces crime and creates a sense of community. Since a large number of Bangladesh’s population resides in Dhaka, it is high time for the relevant authorities to put some serious thought into improving walking conditions for the city dwellers. However, the responsibility for doing so does not lie solely on those involved in urban design and planning. Research on walkability should also be based upon social and economic factors, which can lead to more innovative design solutions inspired from some novel approaches.

References

Ashraf, K. (2022). Metrophilia: How to Love Dhaka. Retrieved 15 June 2022, from https://www.thedailystar.net/recovering-covid-reinventing-our-future/developing-inclusive-and-democratic-bangladesh/news/metrophilia-how-love-dhaka-2965586

Lambert, R. (2020). Walkability in Asian Cities – The City at Eye Level. Retrieved 15 June 2022, from https://thecityateyelevel.com/stories/walkability-in-asian-cities/

Morshed, A. (2018). Why Dhaka is not a walkable city, yet!. Retrieved 15 June 2022, from https://www.thedailystar.net/opinion/perspective/why-dhaka-not-walkable-city-yet-1519132

Morshed, A. (2019). Why not a national footpath policy?. Retrieved 15 June 2022, from https://www.thedailystar.net/opinion/the-grudging-urbanist/news/why-not-national-footpath-policy-1807042

Pak, B., & Verbek, J. (2013). Walkability as a Performance Indicator for Urban Spaces. Crowdsourcing And Sensing – Volume 1 – Computation And Performance, 1.

Rashid, H. (2022). Dhaka: An unwalkable city. Retrieved 15 June 2022, from https://www.thedailystar.net/shout/news/dhaka-unwalkable-city-3026456

Farhat Afzal is an architect, working as an editor and writer in the field of architecture. She coordinates the academic program at Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements, where she is also the editor of its annual publication, Vas. She likes to engage in discussions involving colonialism and post colonial architecture in South Asia, and present her views through expository writings, which have been published in The Daily Star and New Age in Bangladesh. In her spare time, she enjoys photographing old buildings, documenting her reading habits on Instagram and blogging.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

Kim Dovey: Leading Theories on Informal Cities and Urban Assemblage

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “

One Comment

Very good topics to spare your time to thoughts on Walking, particularly in Dhaka.