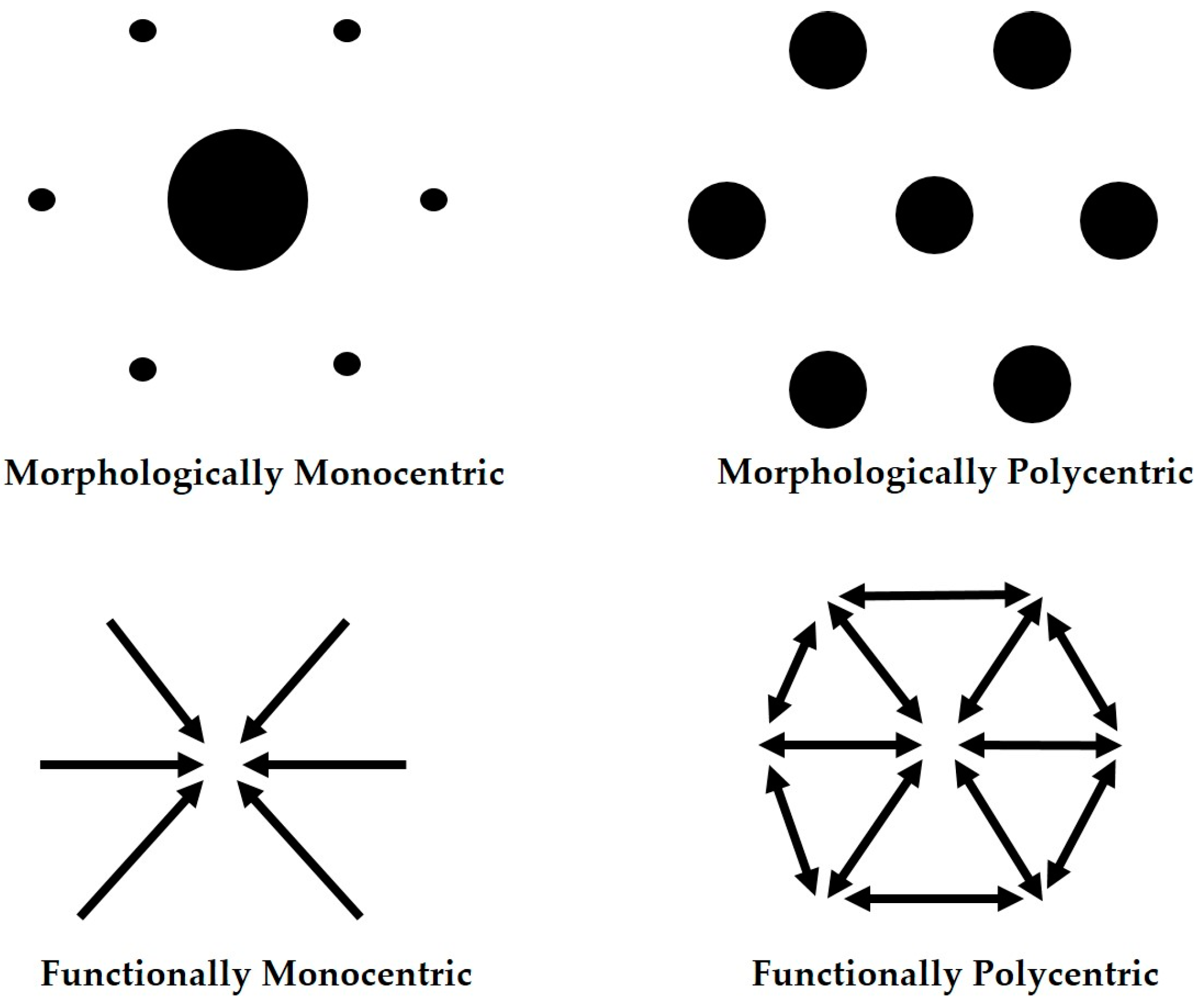

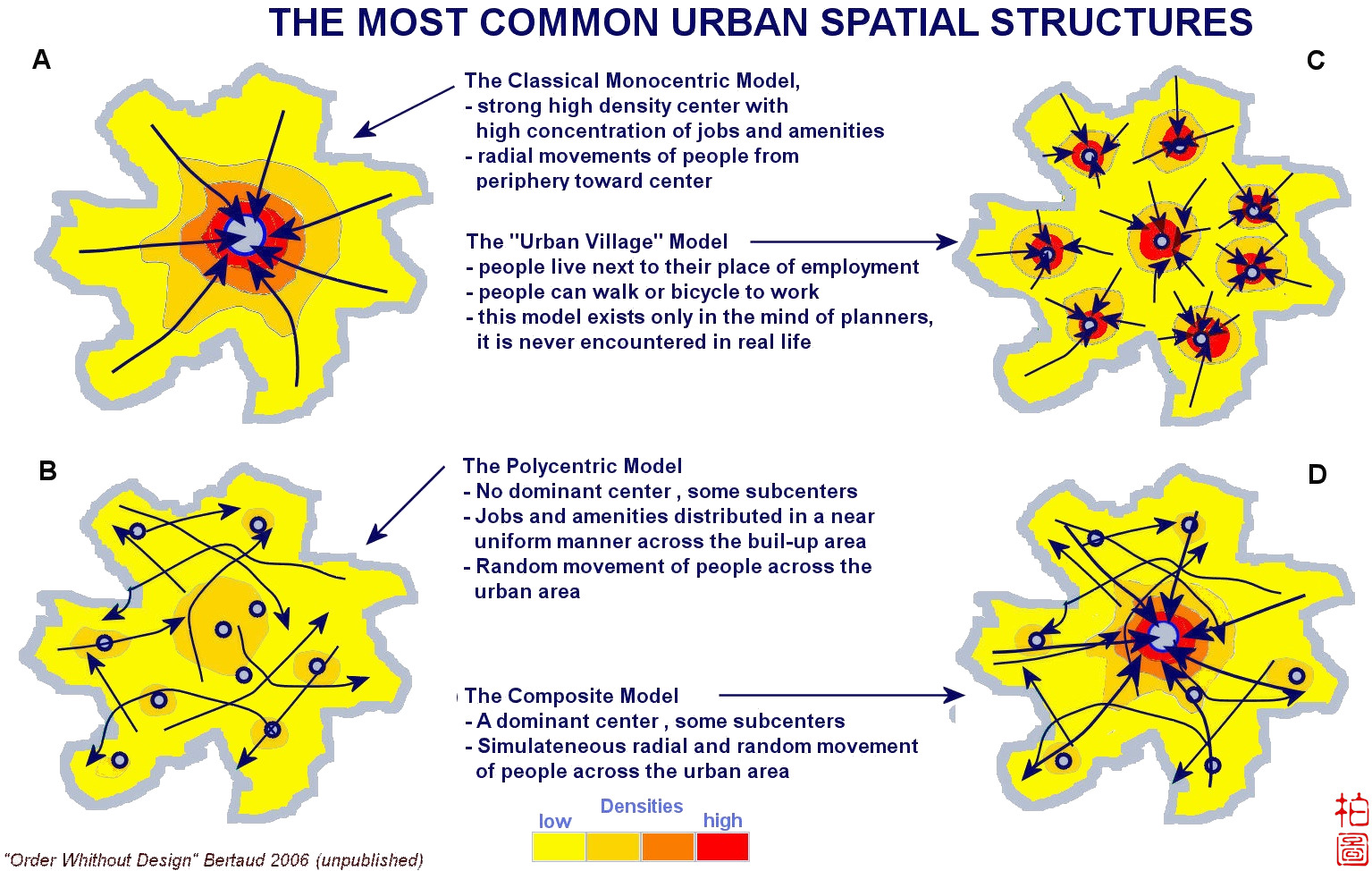

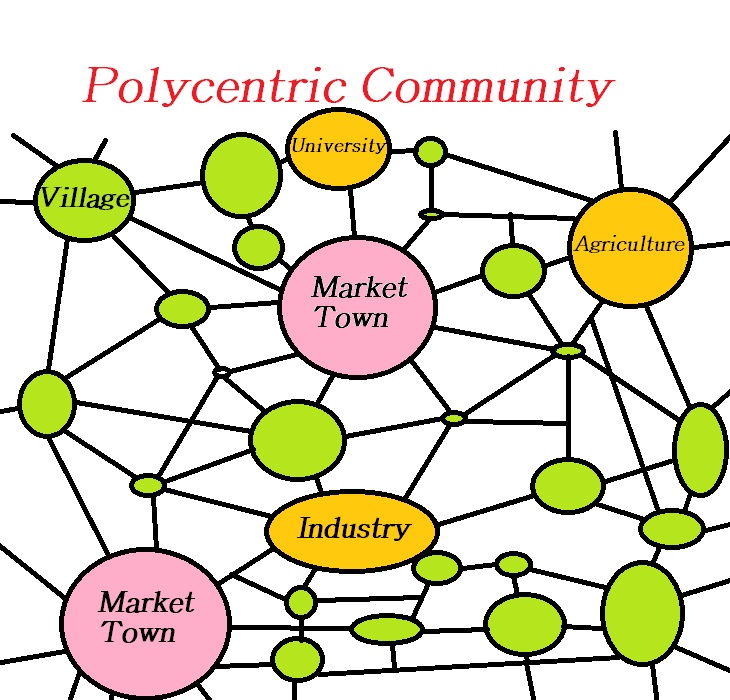

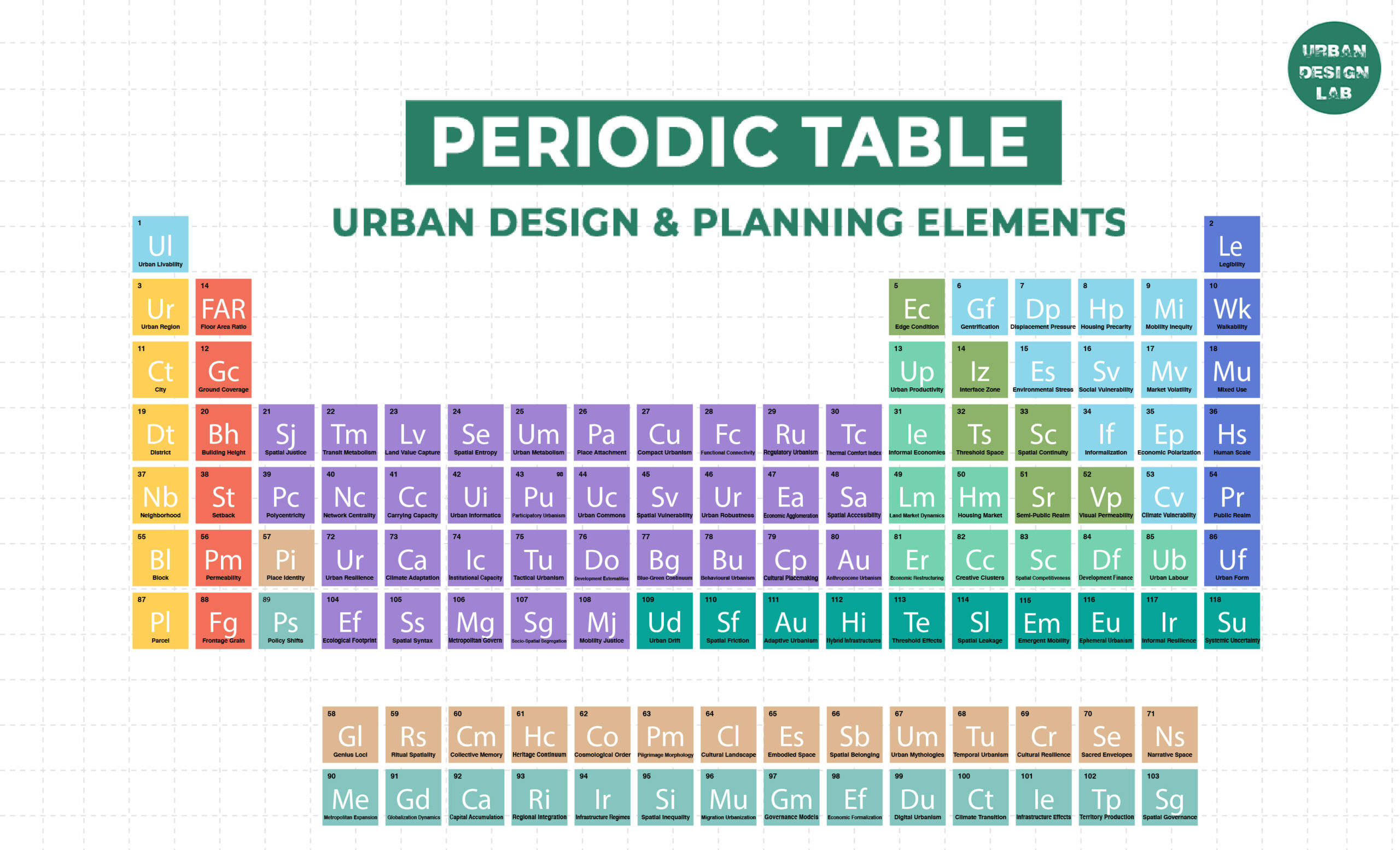

As cities grapple with rapid urbanization, climate volatility, and socio-economic fragmentation, polycentric urbanism emerges as a resilient, adaptive model with multidimensional benefits. Its strength lies in distributing growth, infrastructure, and opportunity across multiple, well-connected centers. Here’s how this model reshapes the urban experience:

1. Reduced Congestion and Load Redistribution

By decentralizing activity hubs, polycentric urbanism alleviates the pressure historically placed on singular downtown cores. This spatial redistribution minimizes traffic bottlenecks, eases transit load on radial corridors, and reduces the spatial mismatch between jobs and housing. The result: a more fluid, efficient, and legible urban mobility network.

2. Enhanced Accessibility and Equitable Urban Access

Proximity becomes a planning principle. With services, jobs, and amenities located across multiple centers, residents experience reduced travel distances and time. This fosters greater accessibility, particularly for historically underserved populations. Polycentricity also supports the 15-minute city ideal, embedding everyday functions within walking or cycling distance.

3. Economic Diversity and Localized Prosperity

A polycentric structure nurtures place-based economies by empowering sub-centers to develop distinct commercial ecosystems. This diversification cushions cities from macroeconomic shocks by reducing dependence on a singular central business district. It also enables small and medium enterprises to thrive in localized clusters, reinforcing inclusive economic development.

4. Sustainable Urban Form and Ecological Performance

Polycentric cities promote mixed-use, transit-oriented development (TOD) and discourage low-density sprawl. This compactness reduces land consumption, curbs automobile reliance, and supports sustainable infrastructure provisioning. Distributed density, when properly calibrated, can significantly lower cities’ ecological footprints and align urban growth with climate resilience objectives.

5. Strengthened Place Identity and Cultural Pluralism

Decentralization facilitates the cultivation of unique neighborhood identities—each center developing its own architectural character, socio-cultural life, and civic traditions. This polyphonic urban texture fosters pride of place, strengthens community bonds, and resists the homogenizing effects of globalization and generic urbanism.

6. Systemic Resilience and Adaptive Capacity

Urban systems structured around multiple nodes are inherently more resilient. They can absorb disruptions—whether economic downturns, infrastructural failures, or environmental shocks—without systemic collapse. Polycentricity allows for redundancy, flexibility, and the localization of responses, which are crucial in an age of polycrisis.

One Comment

Ots really awesome