Book Review: Autonomous Urbanism

Introduction

I write this on a snowy day in a small New Hampshire town, where the size of my neighbors’ garages suggests most households own at least two cars. In suburban neighborhoods like this across the United States, car ownership is deeply intertwined with daily life, practically a requirement for full participation in society. Driving is indispensable for everything—from commuting to work to picking up a cup of coffee. Yet, as someone who has never fully embraced the supposed joy and freedom of sitting behind the wheel, I find myself missing the urban life, where one can navigate the city independently of a car. What I truly appreciate is the spontaneity it offers: the ability to accomplish multiple errands through a series of short, interconnected trips. In the city, density and connectivity eliminate the need for sprawling grocery runs to wholesale stores, and food adventures often stem from serendipitous discoveries made while walking by. Suburbs, for all their appeal—spacious homes, family-friendly environments, and proximity to nature—offer limited mobility options. Even for those who enjoy driving, enduring rush-hour gridlock on the highway is hardly anyone’s idea of a fulfilling way to spend their day.

Could autonomous vehicles (AVs) improve this situation?

Perhaps. If you’ve purchased a car in the last few decades, it likely includes some autonomous features. Meanwhile, companies like Waymo, Zoox, and Cruise have been testing and deploying driverless ride-hailing services across various U.S. cities. Technocrats, investors, and media outlets present a vision of AVs as the next transformative technology—poised to revolutionize not just transportation but also the way we organize our daily lives. However, their vision largely assumes a future anchored in private car ownership and market-driven solutions, overlooking both the state’s potential role and the possibility of integrating AVs into public transit systems. More critically, designers and urban planners appear largely absent from these discussions, leaving the implications of AVs on the built environment—our streets, neighborhoods, and cityscapes—insufficiently explored. It is precisely these overlooked dimensions that Autonomous Urbanism seeks to illuminate.

A Two-Volume Vision: From Framework to Experience

Building upon his graduate thesis, Evan Shieh’s Autonomous Urbanism presents a two-volume road map to an alternative future dubbed “Transitopia”. In this vision, AV technology is harnessed to strengthen public transit systems and repurpose car-dominated spaces, transforming cities into more vibrant and sustainable habitats.

Book 1, which outlines the framework, is divided into two parts. The first opens with a historical analysis of mobility systems and urban forms, challenging the widespread misconception that cities have evolved organically and inevitably into their current car-dependent state. The American dream—a suburban house with a car—represents not a natural evolution but an intentionally cultivated ideal, one that became deeply embedded in the national consciousness. Prior to the automobile, cities accommodated multiple transport modes: horse-drawn carriages and later streetcars shared streets with pedestrians and cyclists in what might be called an organized chaos, with no single mode of movement claiming supremacy.

The advent of automobiles, however, marked a significant turning point, not without resistance. The alarming number of fatalities sparked heated public debates about responsibility and regulation. In response, “Motordom,” a powerful coalition of automobile interest groups, emerged to advocate policies and narratives that prioritized car usage and sales. Rather than adapting automobiles to the preexisting urban fabric, cities were redesigned around them, with spaces carved out exclusively for vehicular traffic at the expense of pedestrian access. A parallel comparison can be drawn to other significant transformations of urban spaces in the same era. Just as children’s play was gradually confined to designated playgrounds instead of streets and vacant lots, and shopping activities were relocated from vibrant street markets to controlled indoor malls, modernist urban planning consistently opted for spatial segregation and regulation over integration and adaptation (Sennett, 2008).

Today, we stand at another crossroads with the advent of AVs. Lessons from the last century reveal that technological innovations are also “infrastructure change-agents that shape urban growth patterns”(Book 1: p.9). The author outlines several possible futures, ranging from a dystopian scenario where AVs intensify urban sprawl and segregation, to the ideal vision of Transitopia, where AVs operate as part of a public transit system managed through public-private partnerships. This vision of Transitopia is supported by a value system that prioritizes human movement over vehicular flow and champions vibrant, multi-purpose public spaces over single-use infrastructure.

The persistence of Autopia—a car-centered urban paradigm—can be attributed to a narrow understanding of mobility, one that only considers automobility, neglecting active modes of transport like walking and cycling, as well as public transit. Efficiency is emphasized over equity, often privileging the mobility of certain groups while marginalizing others. While initiatives such as Complete Streets and Play Streets challenge these misconceptions, the author argues for a more coordinated effort among government, private sector actors, and the public to steer investments toward a positive future, like the Transitopia model envisioned in the book.

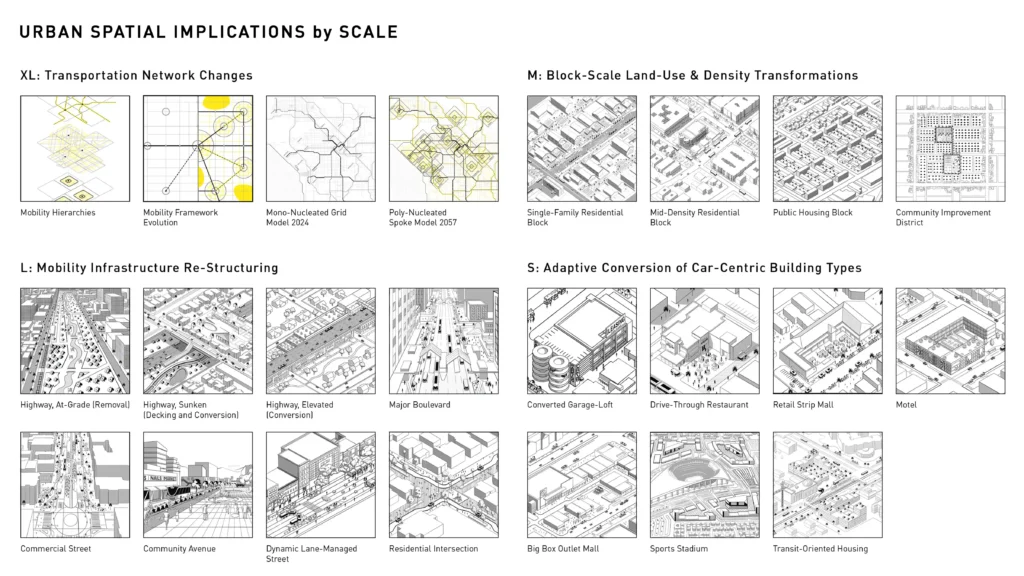

In Book 1’s second part, Los Angeles serves as a case study for transforming a prototypical car-dependent city. Though notorious for its sprawl and entrenched car culture, Los Angeles also demonstrates progressive political will and concrete commitments to expanding public transportation, making it an ideal testing ground for the book’s principles. To help readers envision this alternative future—the idealized best-case scenario—the author selects specific sites across the city and examines them at four distinct scales: XL (regional transportation network), L (mobility infrastructure), M (block), and S (building).

The rationale underpinning this speculative typological design is twofold: first, driverless transportation has the potential to reduce labor costs and increase accessibility through a combination of incentives and subsidies; and second, it can free up vast amounts of land currently dedicated to vehicle movement and storage. With a robust network of autonomous mini-shuttles, rapid buses, and rail systems efficiently moving people, these reclaimed spaces could be repurposed to address urban deficiencies—creating affordable housing, community gardens, ecological corridors, and vibrant public plazas. In this vision, Los Angeles serves as a model for how AV technologies could be leveraged not just for mobility but as catalysts for reimagining and revitalizing urban landscapes.

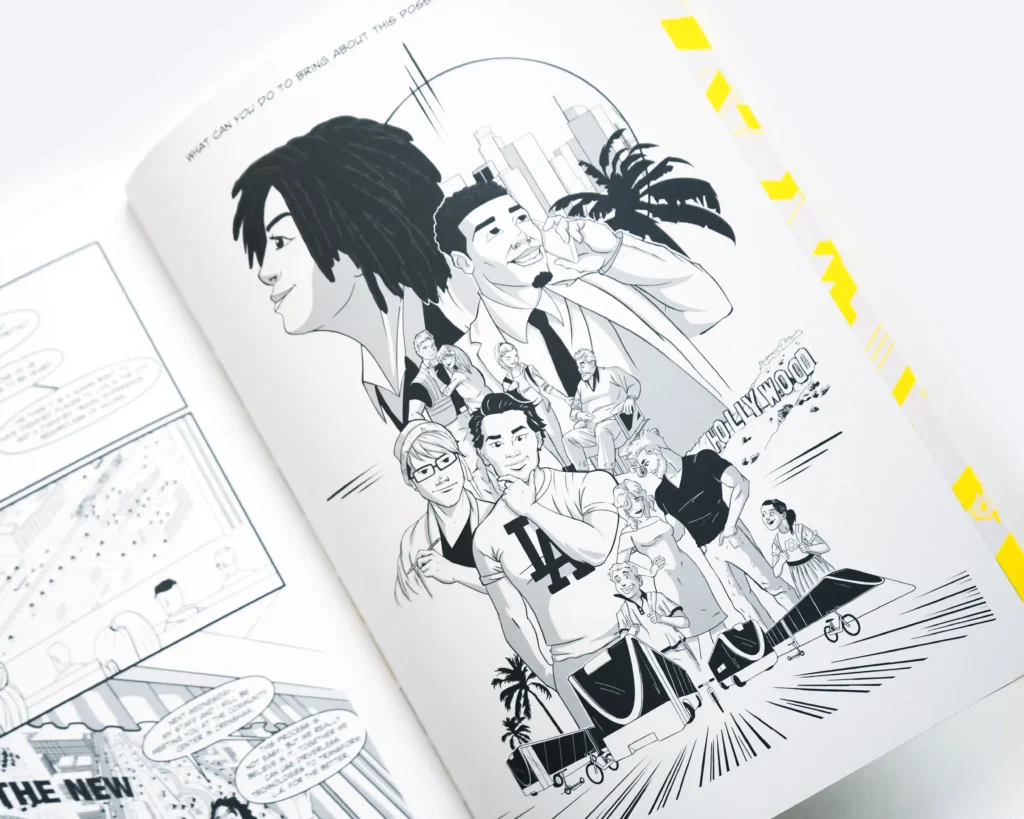

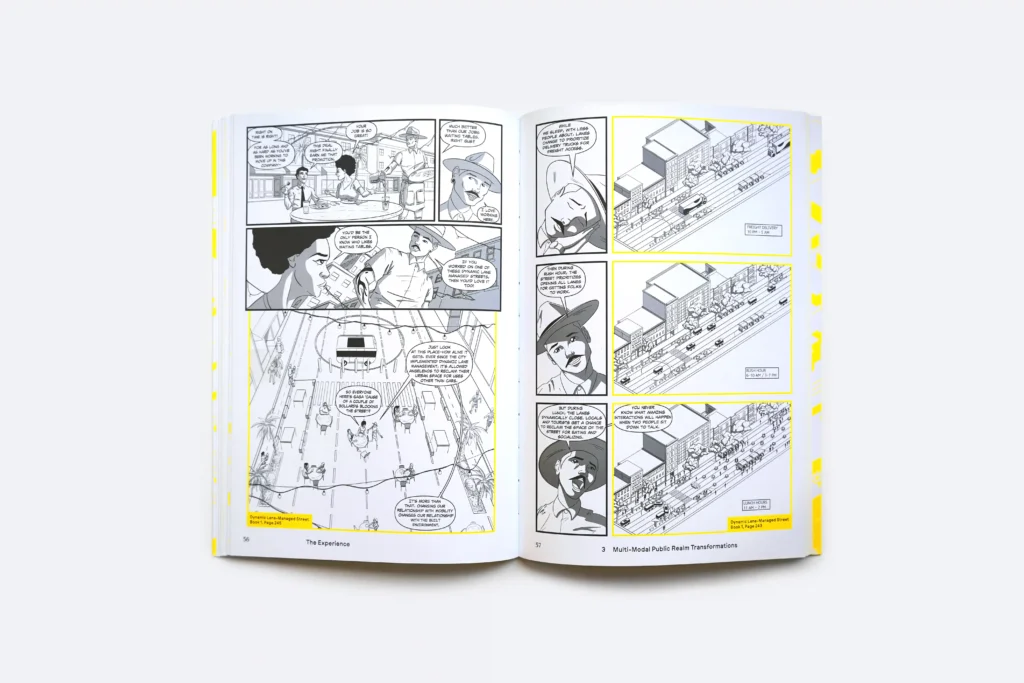

Book 2: The Experience takes the form of an architectural graphic novel, illustrating the everyday lives of Angelenos in the year 2057, when the vision of Transitopia has been fully realized. The use of worldbuilding to visually project the future is a longstanding tradition in the fields of architecture and urban planning, though it has often been met with mixed reactions. The author thoughtfully engages with this history, recognizing the pitfalls of earlier visioning efforts, which were often idealized, overly formal, and shaped by singular perspectives. In contrast, the graphic novel format adopts a “day-in-the-life” narrative style, rooted in a realistic and nuanced portrayal of a complex urban environment.

Through the lives of five distinct households—ranging from a suburban nuclear family to a transit planner—the narrative explores how autonomous vehicles reshape daily routines, social norms, and urban life. This accessible and engaging format broadens the book’s appeal, reaching a wider audience and fostering meaningful dialogue. By inviting readers to position themselves within these narratives, the graphic novel functions as an effective conversation starter, encouraging reflection on the implications of this speculative future.

Critical Assessment

The book’s argument could be further strengthened in two key areas. First, while the book’s multi-scalar framework (XL, L, M, S) effectively illustrates alternative futures—from regional networks to individual buildings—incorporating an additional XS scale, focused on the human body, could provide a more nuanced account of mobile lives and help the case for a human-centered mobility system. Traditional transportation planning and policymaking often regard individuals as agents whose mobility practices are the result of rational calculation. This perspective, along with a dualistic separation of body and mind, obscures the embodied and affective dimensions of everyday mobility, which are increasingly recognized as critical to understanding mobility choices (Sheller, 2004; Spinney, 2009; Doughty and Murray, 2016; Lee, 2016).

The human body, as the most immediate scale of experience, is where embodiment, affect, and the everyday converge. Mobility practices are not just functional but deeply embodied and emotional, shaped by habits, routines, and sensory experiences. When we take the human body seriously in automobility research, driving can be reconceptualized as a “bodily habit that is co-constituted within an automobile” (Harada and Waitt, 2013, p. 145). This shift in perspective encourages the use of ethnographic methods to explore the rhythms of movement, the alignment of car ownership with life trajectories, and the subjective experience of driving. For example, Sheller (2004) studies the “emotional geographies” (p. 224) of driving, revealing deep psychological and cultural attachments that make car dependency particularly resistant to change.

At the same time, the everyday is a space of possibility, where entrenched norms can be challenged. Doughty and Murray (2016) explore how institutional mobility discourses—rooted in notions of modernity, freedom, and, more recently, morality (e.g., sustainable mobility choices and responsible citizens)—are affirmed in some contexts but disrupted in others by everyday mobility practices and discourses. Incorporating insights from this scholarship, along with speculative ideas about how AVs might transform the sensory and emotional landscapes of mobility, would enrich the book’s analysis. It could also complement the narrative arc of the graphic novel, grounding its futuristic scenarios in a deeper exploration of embodied experiences and cultural dynamics.

Second, while the author expresses “cautious optimism” (Book 2: p.20) and purposefully envisions a successful 2057 scenario, the portrayed transitions appear notably frictionless, with technological and social adaptations proceeding smoothly and resistance largely absent or swiftly resolved. An interim scenario set around 2035 could be valuable in illustrating the messy process of transformation—showing how different stakeholders navigate conflicts, how new social norms emerge through trial and error, and how communities work through initial resistance to change.

Conclusion

Autonomous Urbanism achieves a commendable balance between breadth and depth. Whether you are an AV technocrat, an urban designer or planner, or an advocate for equitable cities, the book offers valuable insights tailored to your perspective and provides opportunities for learning. It complements its grounded approach with visionary thinking, offering a timely moment of reflection amidst the rapid evolution of AV technology. As historian Melvin Kranzberg reminds us, “Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral.” While most current discussions remain narrowly focused on the technology of AVs, this book challenges us to consider what specific social and urban goals AVs should serve.

References:

- Doughty, K. and Murray, L. (2016) ‘Discourses of Mobility: Institutions, Everyday Lives and Embodiment’, Mobilities, 11(2), pp. 303–322. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2014.941257.

- Harada, T. and Waitt, G. (2013) ‘Researching Transport Choices: The Possibilities of “Mobile Methodologies” to Study Life‐on‐the‐Move’, Geographical Research, 51(2), pp. 145–152. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-5871.2012.00774.x.

- Lee, D.J. (2016) ‘Embodied bicycle commuters in a car world’, Social & Cultural Geography, 17(3), pp. 401–422. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2015.1077265.

- Sennett, R. (2008) The uses of disorder: personal identity and city life. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press.

- Sheller, M. (2004) ‘Automotive Emotions: Feeling the Car’, Theory, Culture & Society, 21(4–5), pp. 221–242. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276404046068.

- Spinney, J. (2009) ‘Cycling the City: Movement, Meaning and Method’, Geography Compass, 3(2), pp. 817–835. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2008.00211.x.

Claire Zhuo Pang

About the Author

Claire Zhuo Pang is an architect and urban designer. Her work with refugee children and migrant communities inspires her PhD research on migrant newcomers and urban spaces. Passionate about writing, she shares insights about urbanism, academic life, and everyday observations through her blog, weaving together professional expertise with personal narratives.

Related articles

Kim Dovey: Leading Theories on Informal Cities and Urban Assemblage

Henri Lefebvre’s Right to the City: Shaping Everyday Urban Life

UDL Illustrator

Masterclass

Visualising Urban and Architecture Diagrams

Session Dates

17th-18th January 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “