Elephant & Castle Regeneration, London: Balancing Affordable Housing with Gentrification Pressures

Elephant & Castle, a historically diverse and working-class neighborhood in South London, is undergoing a large-scale regeneration process involving public-private partnerships and significant investment. While the project promises improved infrastructure, housing, and public spaces, it also raises serious concerns about affordability, displacement, and cultural erasure. The demolition of the Heygate Estate and the old shopping center has been symbolic of a broader trend: long-term residents being priced out or relocated in favor of market-rate developments. Community groups have mobilized to demand more equitable planning, including genuine affordable housing and protections for migrant-owned businesses, particularly those of the Latin American community. Meanwhile, institutions like the London College of Communication contribute to both opportunity and tension in the neighborhood’s evolution. This regeneration reflects the challenges faced by many global cities trying to balance economic growth with social equity. Without meaningful policies to ensure inclusivity, the transformation risks undermining the very communities that give Elephant & Castle its unique identity.

A Neighborhood in Transformation

Elephant & Castle, located in the heart of South London, has become a focal point for one of the most ambitious urban regeneration projects in the UK. Long known for its rich multicultural identity and working-class character, the area is undergoing a radical transformation, driven by significant investment from both public and private sectors. The official narrative emphasizes improved transport links, new housing, cultural spaces, and a revitalized economy. However, behind this optimistic vision lies a more complex and contested reality. For many residents, regeneration feels more like displacement. The demolition of familiar landmarks — such as the old shopping center — and the rapid construction of luxury high-rises are changing the social fabric of the area. Long-time communities, particularly from migrant and low-income backgrounds, are feeling squeezed out, both economically and culturally. While change is inevitable in a growing city like London, the pace and nature of transformation in Elephant & Castle raise important questions about who truly benefits. Is the area being improved for its residents, or in spite of them? This tension sits at the heart of the regeneration debate, making Elephant & Castle a powerful lens through which to explore the broader dynamics of urban change.

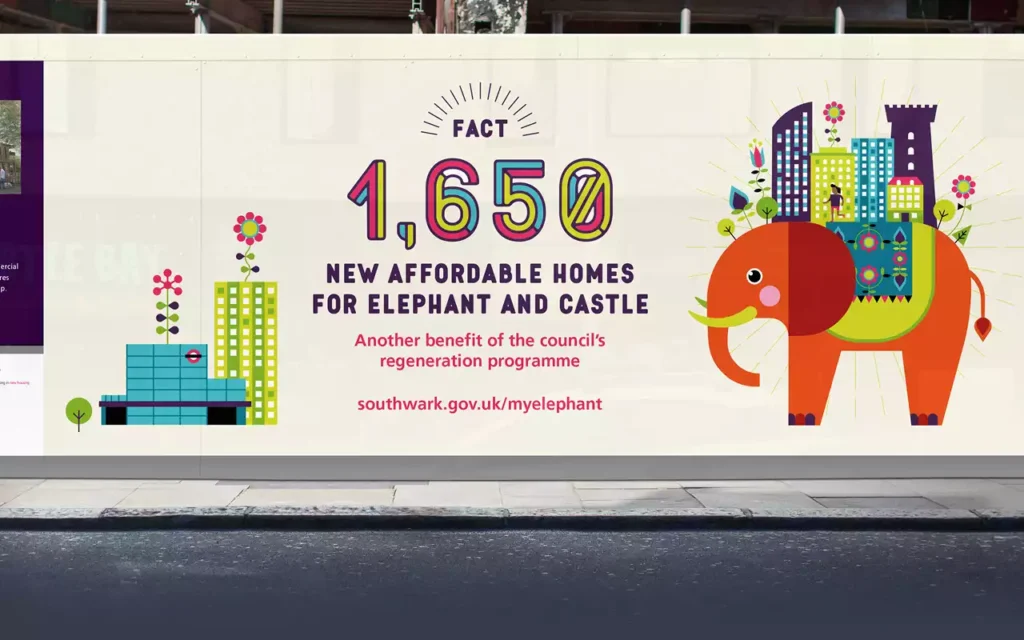

The Affordable Housing Dilemma

One of the central promises of the regeneration strategy in Elephant & Castle is the provision of new homes, including a substantial number labeled as “affordable.” However, what qualifies as affordable in London’s overheated housing market remains highly controversial. The official definition often includes housing that costs up to 80% of market rent — still unaffordable for many local residents whose incomes fall well below the London average. The demolition of the Heygate Estate, once home to over 1,200 social housing units, marked a turning point. In its place, new developments like Elephant Park offer modern, high-spec apartments, but only a small fraction are genuinely affordable in the social housing sense. Residents who were displaced were promised the right to return, but logistical, financial, and policy barriers have made that return nearly impossible for many. Critics argue that the regeneration has prioritized profit over people, replacing low-income families with wealthier newcomers, and thereby accelerating gentrification. The housing crisis in Elephant & Castle is not just about numbers — it’s about accessibility, permanence, and fairness. Without a meaningful commitment to truly affordable housing, regeneration risks becoming little more than a euphemism for urban exclusion.

Source: Website Link

The Ambiguity of the “Mixed Community”

The concept of a “mixed community” has become a recurring phrase in urban planning rhetoric, especially in projects like Elephant & Castle. Developers and local authorities often use the term to suggest a social balance: a vision of diverse income groups, ethnicities, and age demographics coexisting in one revitalized area. On paper, this idea appeals to a wide audience — it implies inclusivity, social cohesion, and economic opportunity. But in practice, the implementation of this model often skews toward exclusion rather than integration. New developments frequently cater to middle- and upper-income groups, while so-called affordable units remain limited, oversubscribed, or too costly for those most in need. The “mix” becomes symbolic rather than functional. Wealthier residents benefit from modern architecture, cleaner streets, and improved services, while long-standing working-class communities face rising costs and cultural dislocation. Moreover, these groups rarely interact in meaningful ways, occupying parallel social worlds despite physical proximity. In Elephant & Castle, the promise of mixed living too often translates into a one-directional flow of displacement and replacement. Without structural protections for existing residents the mixed community remains more of an idealized concept than a lived reality.

Grassroots Resistance

Despite the scale and momentum of the regeneration project, resistance has grown from the ground up. Community groups, local activists, and housing campaigners have been organizing for years to challenge what they see as a top-down redevelopment agenda that disregards the voices of those most affected. Organizations like Latin Elephant, Southwark Defend Council Housing, and 35% Campaign have played crucial roles in exposing the gaps between official promises and actual outcomes. Their efforts include public demonstrations, community consultations, policy critiques, and legal interventions aimed at increasing the share of truly affordable housing and preserving local culture. In some instances, grassroots activism has led to measurable gains — such as temporary halts on demolition, revised planning permissions, commitments to social rent units. Yet the struggle is ongoing and deeply uneven. Many residents feel that consultation processes are performative, offering the illusion of participation without real influence over decisions. Others note how language barriers and digital exclusion further marginalize certain voices, particularly among migrant communities. What emerges is a tale of unequal power: well-funded developers versus community organizers operating on limited resources. Still, the resilience and creativity of local resistance remain a vital counterforce in shaping the future of Elephant & Castle.

Cultural Identity at Risk

Elephant & Castle is not just a geographic location — it is a cultural landmark, especially for London’s Latin American community. Over the past decades, the area has grown into an unofficial Latin quarter, home to restaurants, shops, churches, and social clubs that serve as vital cultural and economic hubs. Migrants from Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, and other countries have made the area their own, infusing it with vibrancy, entrepreneurial energy, and a strong sense of belonging. However, regeneration has brought closures and relocations. The demolition of the shopping center displaced many Latin businesses, some of which were offered alternative locations far from their customer base — or none at all. For these communities, the threat is not only physical eviction but cultural erasure. Gentrification doesn’t just change who lives in a place; it changes what that place means. The loss of communal spaces, familiar languages, and local events contributes to a gradual unraveling of identity. Although initiatives like Latin Elephant aim to preserve this cultural presence, they often face institutional indifference or token gestures. Protecting cultural identity in regeneration requires more than symbolic inclusion; it demands long-term, structural commitments.

Struggling to Strike a Balance

Elephant & Castle has become a case study in the broader struggle to reconcile urban development with social justice. On the surface, regeneration brings undeniable improvements: upgraded public transport via the new Underground station, investments in pedestrian and cycling infrastructure, better lighting, and new green spaces like Elephant Park. These changes enhance quality of life — but for whom? While incoming residents may enjoy a higher standard of living, long-standing communities often feel these benefits are not meant for them. Rising rents, increasing council tax, and the loss of public amenities make it harder for working-class families to remain in place. The irony is sharp: public investment, once demanded by residents to improve neglected infrastructure, now serves as a magnet for private developers and wealthier newcomers. Policies to mitigate displacement often lag behind development, or are diluted during negotiations with private stakeholders. Meanwhile, short-term fixes — such as temporary housing schemes or rent discounts — do little to address the structural forces behind gentrification. Striking a fair balance between renewal and equity demands more than good intentions. It requires robust regulation, democratic planning, and a genuine commitment to maintaining the social diversity that has long defined Elephant & Castle.

Promises of Public-Private Partnerships

At the heart of the regeneration effort lies a partnership model between local authorities and private developers. This approach — now dominant across the UK’s urban planning landscape — is intended to leverage private capital for public good. In practice, however, these partnerships often tilt heavily toward the interests of large real estate firms. Southwark Council has defended the regeneration plans by citing financial constraints and the need to attract investment to fund public improvements. But critics point to opaque planning processes, under-delivery of affordable housing, and lack of accountability as major flaws in the model. The redevelopment of the Heygate Estate and the shopping center, for example, was driven by multibillion-pound developers like Lendlease, who promised a mixed-income future but largely delivered market-rate units. Community benefit agreements — where they exist — are often vague or unenforced. Moreover, the language of “regeneration” is frequently used to obscure the economic motivations behind urban change, framing controversial developments as necessary progress. True partnership should involve equal power and shared decision-making, yet in Elephant & Castle, the scales are clearly unbalanced. A more equitable model would foreground community land trusts, public control over key assets, and transparency throughout every stage of planning.

The University as a Driver of Change

The presence of the London College of Communication (LCC), part of the University of the Arts London, has brought both opportunity and complexity to Elephant & Castle’s transformation. On one hand, the university energizes the area through its creative output, student population, and cultural events. It raises awareness of local issues and has the potential to act as a bridge between communities and institutions. On the other hand, LCC contributes to gentrification. The growing student population increases housing demand, raising rents and transforming nearby streets into student-oriented zones. Local businesses often shift to serve this new demographic, while long-time residents find services increasingly unaffordable or unrecognizable. Though the university has led community engagement projects, these are sometimes seen as extractive — using the neighborhood for academic purposes without long-term commitment or systemic impact. To become a genuinely positive force, LCC must move beyond surface involvement. It should embed social responsibility in its development plans, advocate for truly affordable housing, and support local businesses. In doing so, the university can reposition itself not just as an occupant, but as an accountable, long-term stakeholder in the community’s future.

Conclusion

The regeneration of Elephant & Castle is a powerful illustration of the paradoxes inherent in contemporary urban development. It reveals how policies designed to revitalize a neighborhood can, without careful planning and inclusive frameworks, contribute to the displacement of the very people they claim to support. The case challenges us to ask difficult questions: Who gets to shape the future of a city? Who is welcome in a “regenerated” space — and who is written out? It also reminds us that urban development is never neutral; it reflects underlying power dynamics, values, and priorities. A successful regeneration should not be judged solely by its skyline or economic return, but by its ability to preserve community, guarantee affordability, and recognize cultural identity as a vital urban asset. Elephant & Castle is still in flux, and the outcome is not yet determined. There remains room to reimagine a model that places equity at its core — one that sees development not as a zero-sum game but as a shared, participatory process. Only then can we truly speak of urban progress that includes, rather than excludes, those who have called this place home for generations.

References

Hasenberger, H., & Nogueira, M. (2022). Subverting the “migrant division of labor” through the traditional retail market: the London Latin Village’s struggle against gentrification. Urban Geography, 45(1), 53-72. Retrieved by https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2022.2146925

Kollewe, J. (2024, May). ‘It will take two decades to fix the housing crisis’: The developer reshaping south London. Retrieved by The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/business/article/2024/may/14/it-will-take-two-decades-to-fix-the-housing-crisis-the-developer-reshaping-south-london

Lees, L., & Ferreri, M. (2018, September). Resisting gentrification on its final frontiers: lessons from the Heygate Estate in London (1974-2013). Cities, 57, 14-24.

Minton, A. (2018, September). The Price of Regeneration. Retrieved by Places Journal: https://placesjournal.org/article/the-price-of-regeneration-in-london/

Minton, A. (2025, May). A new kind of gentrification is spreading through London – and emptying out schools. Retrieved by The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2025/may/26/placemaking-gentrification-london-luxury-apartments-expensive-restaurants-schools

Carmela Zizzania

About the Author

Passionate about urban planning, architecture, and sustainability, she holds a Master’s degree in Building Engineering – Architecture from the University of Naples Federico II. Her academic path combines technical and design knowledge with a strong interest in urban regeneration and public space. She has conducted research on urban quality of life and sustainability, and gained experience in project development, cost estimation, urban codes, and public procurement. She is particularly interested in inclusive and resilient urban strategies, and seeks to apply interdisciplinary approaches to shape cities that are more livable, equitable, and environmentally conscious.

Related articles

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “

21 Comments

You explained it in such a relatable way. Well done!

Great article! I’ll definitely come back for more posts like this.

Thank you for covering this so thoroughly. It helped me a lot.

I enjoyed every paragraph. Thank you for this.

Your writing style makes complex ideas so easy to digest.

I appreciate the depth and clarity of this post.

Very useful tips! I’m excited to implement them soon.

This was easy to follow, even for someone new like me.

Your thoughts are always so well-organized and presented.

I appreciate your unique perspective on this.

This topic is usually confusing, but you made it simple to understand.

I’ll be sharing this with a few friends.

You really know how to connect with your readers.

Thank you for covering this so thoroughly. It helped me a lot.

I like how you presented both sides of the argument fairly.

This was very well laid out and easy to follow.

You write with so much clarity and confidence. Impressive!

I appreciate your unique perspective on this.

You’ve built a lot of trust through your consistency.

Such a simple yet powerful message. Thanks for this.

What an engaging read! You kept me hooked from start to finish.