Bratislava’s Sky Park 2024 by Zaha Hadid Reimagines Industrial Legacy

Sky Park Bratislava is a major urban regeneration project that transforms a decommissioned industrial zone into a vibrant mixed-use district. Designed by Zaha Hadid Architects, the development features four towers housing over 700 apartments, office and retail space, and a large public park. Central to the project’s identity is the adaptive reuse of the Jurkovič Heating Plant, preserved as a cultural anchor and coworking hub that bridges Bratislava’s industrial past with its future as a creative city.

More than a residential development, Sky Park prioritizes openness, walkability, and inclusive design. The park offers not just green space but also informal play areas, woodland trails, fitness zones, and gathering spots, designed to support health, interaction, and community life. Unlike the enclosed perimeter blocks typical of post-socialist housing, Sky Park fosters connectivity, linking the Old Town and the Danube embankment with new pedestrian and cycling infrastructure.

By placing the public realm and social cohesion at the heart of its master plan, the project offers a compelling model for post-industrial urban redevelopment. Sky Park illustrates how Central European cities can address housing demand, sustainability goals, and civic identity through thoughtful, mixed-use design rooted in both context and ambition.

Introduction: Reclaiming the Industrial Edge of Bratislava

Sky Park Bratislava is a transformative urban development designed by Zaha Hadid Architects that revitalizes a former industrial site in Slovakia’s capital. The project features four striking towers that combine residential, office, and retail spaces, creating a vibrant mixed-use community. The design emphasizes fluid, organic forms characteristic of Hadid’s work, integrating green public spaces and pedestrian pathways to foster connectivity and social interaction. By reclaiming a previously underutilized area, Sky Park not only provides much-needed housing and amenities but also sets a new standard for sustainable urban regeneration in Central Europe. The scheme preserves and repurposes historic industrial structures, blending Bratislava’s architectural heritage with contemporary design. This approach enhances the city’s skyline while promoting environmental responsibility through the use of energy-efficient technologies and extensive landscaping. Sky Park has become a landmark destination, illustrating how innovative architecture can drive urban renewal and improve the quality of life for residents and visitors alike.

Site Legacy and Development Rationale

At the heart of Sky Park’s redevelopment is the adaptive reuse of the Jurkovič Heating Plant, one of the last surviving structures from Bratislava’s former industrial district. Originally constructed between 1941 and 1944, the plant was designed in the functionalist style and attributed to the renowned Slovak architect Dušan Jurkovič (The Slovak Spectator, 2022). Declared a national cultural monument in 2008, it narrowly escaped demolition, a fate that claimed most surrounding factories, thanks to growing public pressure and heritage advocacy. Rather than erasing the past, the developers integrated the building into the new district, restoring its core structural features, including three concrete storage bins that now define its interior. Today, the plant houses over 5,000 square meters of space, primarily used for coworking, events, and cultural programs targeting creative industries, startups, and the wider public. This transformation from energy hub to innovation space speaks not only to sustainability in architecture but also to the value of retaining continuity in urban memory. It now serves as a civic anchor within the Sky Park complex, bridging industrial heritage with a forward-looking vision for mixed-use urban life (Liptáková, 2018).

Source: Website Link

Mixed-Use Development and Urban Block Structure

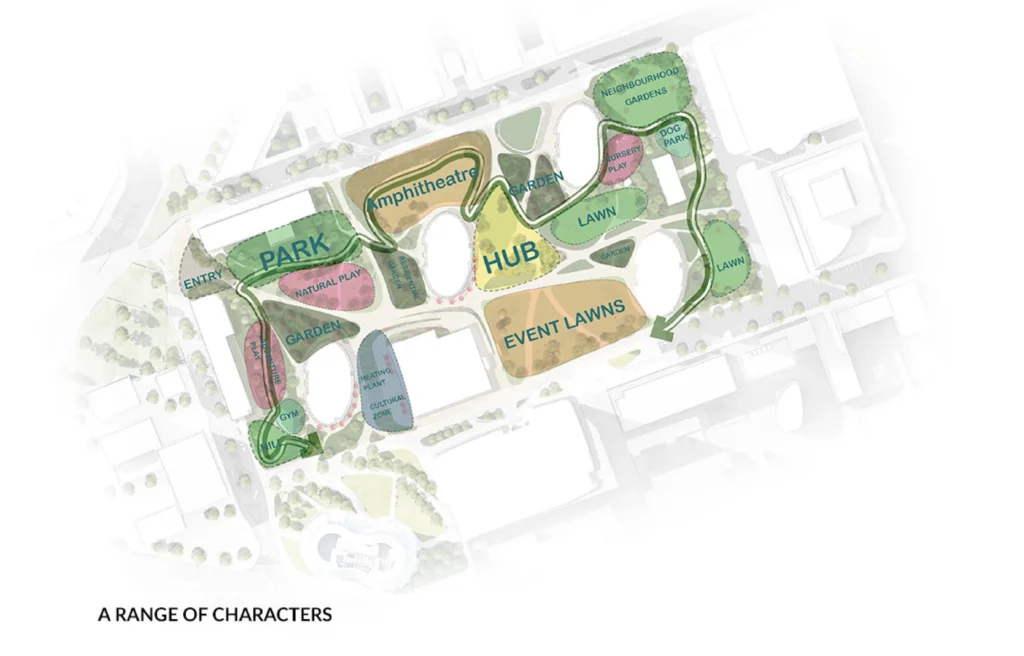

At the core of Sky Park’s identity is its integration of public space and landscape, centered around a 20,000–30,000 square meter park that wraps the towers and connects the development to its surroundings. Designed by Townshend Landscape Architects in collaboration with Zaha Hadid Architects, the park replaces a sealed-off industrial plot with a continuous, walkable environment that supports physical activity, mental health, and everyday use (Townshend Landscape Architects, 2018). Amphitheaters, orchards, dog parks, and picnic lawns are integrated with running tracks and play areas, creating a truly mixed-use green space. The design avoids the enclave-like perimeter blocks proposed by other competitors, opting instead for permeability and access. Entrances from the east and south open the site to surrounding neighborhoods and transit links, while mounded terrain and tree cover create diverse microenvironments within the park. By placing open space at the center of its concept, Sky Park redefines greenery not as a buffer or leftover land, but as civic infrastructure essential to urban life (Kwok, 2017).

Mobility, Access, and Integration into the City

More than a backdrop, Sky Park’s public realm is designed as a social engine. Central to this is its child-friendly, playable landscape strategy, which prioritizes freedom, inclusivity, and community-building. Instead of isolating play in one corner, the master plan disperses play features throughout the park—embedded in terrain, trails, and incidental spaces—to support interaction across age groups and backgrounds (Townshend Landscape Architect, 2018). The inclusion of open gyms, fitness trails, and flexible lawns accommodates users of different needs and routines. Tree-lined entrances with integrated seating serve as social nodes where families, workers, and visitors cross paths. Unlike the gated layouts of many post-socialist housing blocks (‘paneláks’), Sky Park fosters informal encounter and shared ownership of public space (Lynch, 2017). This approach turns everyday use—playing, exercising, resting—into opportunities for building social cohesion, particularly important in high-density areas where private space is limited. Designed for long-term adaptability, the landscape matures with the community, helping new habits and relationships take root over time.

Public Realm, Open Space, and Cultural Anchoring

Sky Park’s greatest urban value lies in how it reconnects a previously sealed-off industrial tract with surrounding neighborhoods (Lynch, 2017). Located between the Old Town and the Danube embankment, the site now offers a series of pedestrian and cycling links that bridge commercial, cultural, and residential zones (Arch2O, 2017) Shaded woodland walks, outdoor trails, and wide social thresholds make the park not just a space for movement, but one of lingering and encounter. Unlike the inward-facing housing blocks that dominated Slovakia’s postwar era, Sky Park’s layout invites circulation and openness, reinforcing its role as a community asset rather than a privatized enclave (Lynch, 2017). Cars are pushed underground, freeing up the ground plane for people and encouraging non-motorized mobility (DÖRKEN, 2020). Commercial and coworking spaces, especially within the repurposed heating plant, draw foot traffic from beyond the residential base, ensuring that this isn’t just a place to live but a shared urban node (Liptáková, 2019). In both design and programming, Sky Park works to transform a formerly disconnected zone into a porous and fully integrated part of the city.

Conclusion

Sky Park Bratislava offers more than a striking set of towers; it represents a shift in how cities can reclaim industrial land through thoughtful, mixed-use planning. By combining housing, offices, public green space, and cultural infrastructure, the project creates a balanced urban district that serves both daily needs and long-term resilience. The reuse of the Jurkovič Heating Plant anchors the development in local heritage, while the walkable public realm and open-access park demonstrate how landscape can shape social life. Rather than functioning as a self-contained enclave, Sky Park extends the city, knitting formerly fragmented spaces into a cohesive urban fabric. In doing so, it challenges the legacy of isolated housing blocks and sets a precedent for integrated, human-scaled growth in Bratislava and beyond. As Central European cities face pressure to densify, regenerate, and decarbonize, Sky Park shows how these goals can converge in a single, well-executed master plan.

References

- Arch2O. (2017, May 23). Construction begins for zaha hadid architects’ mixed-use “sky park” in slovakia – Arch2O.com. Arch2O. https://www.arch2o.com/construction-begins-zaha-hadid-architects-mixed-use-sky-park-slovakia/

- DÖRKEN. (2020). The solutions by DÖRKEN for the prominent elements of the SKY PARK project. DÖRKEN. https://www.doerken.com/global/en/services/references/delta/skypark-bratislava

- Kwok, N. (2017, May 22). Zaha hadid architects unveils sky park masterplan for bratislava. Designboom. https://www.designboom.com/architecture/zaha-hadid-architects-unveil-skypark-bratislava-slovakia-05-22-2017/

- Liptáková, J. (2018, August 24). Historical heating plant will return to life with a different function. SME.Sk. https://spectator.sme.sk/culture-and-lifestyle/c/historical-heating-plant-will-return-to-life-with-a-different-function

- Liptáková, J. (2019, June 5). Zaha Hadid project brings a new public park to Bratislava. SME.Sk. https://spectator.sme.sk/culture-and-lifestyle/c/zaha-hadid-project-brings-a-new-public-park-to-bratislava

- Lynch, P. (2017, May 22). Zaha hadid architects breaks ground on sky park development on industrial site in bratislava. ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily.com/871863/zaha-hadid-architects-breaks-ground-on-sky-park-development-on-industrial-site-in-bratislava

- The Slovak Spectator. (2022, December 9). Jurkovič heating plant in Bratislava receives global architecture award. SME.Sk. https://spectator.sme.sk/culture-and-lifestyle/c/jurkovic-heating-plant-in-bratislava-receives-global-architecture-award

- Townshend Landscape Architect. (2018). Townshend Landscape Architect. Sky Park. https://townshendla.com/projects/sky-park-94/

Muhammad Zeyd Arhan Juan Ramadhan

About the Author

MZAJ Ramadhan is an emerging urban researcher with a strong interest in sustainable futures, climate resilience, and ecological urbanism. His academic work explores the intersection of climate change, urban resilience, and urban design, with a particular focus on the solarpunk movement. With a background rooted in design thinking, he aims to bridge the gap between visionary concepts and practical applications in urban design and planning.

Related articles

UDL Illustrator

Masterclass

Visualising Urban and Architecture Diagrams

Session Dates

28th-29th March 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “