Shifting to a Walkable City: Six Steps to Walkability

The concept behind walking

We can say without thinking too much, that cities were, over time, more designed for motorized transport than for pedestrians. And even today, governments are more interested in investing in road infrastructure than in encouraging people to walk or use alternative modes of transportation. Bringing about a change in the way of thinking about displacement is not easy. Successfully reducing car use requires much more than just taking cars off the road. It is necessary to redistribute resources, reverse priorities and transform public spaces into more people-friendly places (Yanocha, 2021).

According to Jeff Speck, a city planner and urban designer who advocates for more walkable cities, the concept of walkability encompasses characteristics such as 1) Be useful: The majority of daily activities are close at hand and well-organized; 2) Safety: Streets that are meant to be safe for pedestrians and to make them feel safe; 3) Comfort: Urban streets as living rooms in the open air; and 4) Be interesting: Sidewalks that dialogue with unique buildings and active facades – after all, the pedestrian must choose to move on foot, and to make that choice, without a doubt, quality is a necessity (Speck, 2012).

Walking is essential to people’s daily lives and is the simplest, most sustainable, and cheapest means of transport – even if in certain contexts it can be dangerous and difficult. As the cities’ urbanization process evolved and focused on promoting travel by car, the importance of sidewalks and the quality of public spaces for pedestrians was losing importance not only in the richest nations but especially in developing countries. Also, even though the use of public transport and walking tend to be more common in low-income cities, infrastructure, resources, and investments may be insufficient (Andrade & Linke, 2017).

Despite not being an affordable option for most people, the number of private vehicles is increasing in urban areas in many low-income and lower-middle-income countries. Any successful-reduction program must ensure that the needs of low-income and marginalized populations are recognized and addressed and that these traffic people do not pay a disproportionately greater price as a result of the policy than wealthy ones (Yanocha, 2021).

Why is walkability important?

As per the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), we are living in a climate crisis and the time for action is right now. Published in February, Chapter 8 of the 2022 IPCC report says that 67% to 72% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions are from urban areas, where 50% of the world’s population resides. These greenhouse gas emissions coupled with multiple other factors have created a situation where a climate catastrophe is more than likely to occur.

Failure to act now will result in temperatures soaring to 3°C which will lead to catastrophic consequences such as longer warmer periods, shorter colder periods, increasing heatwaves, etc.

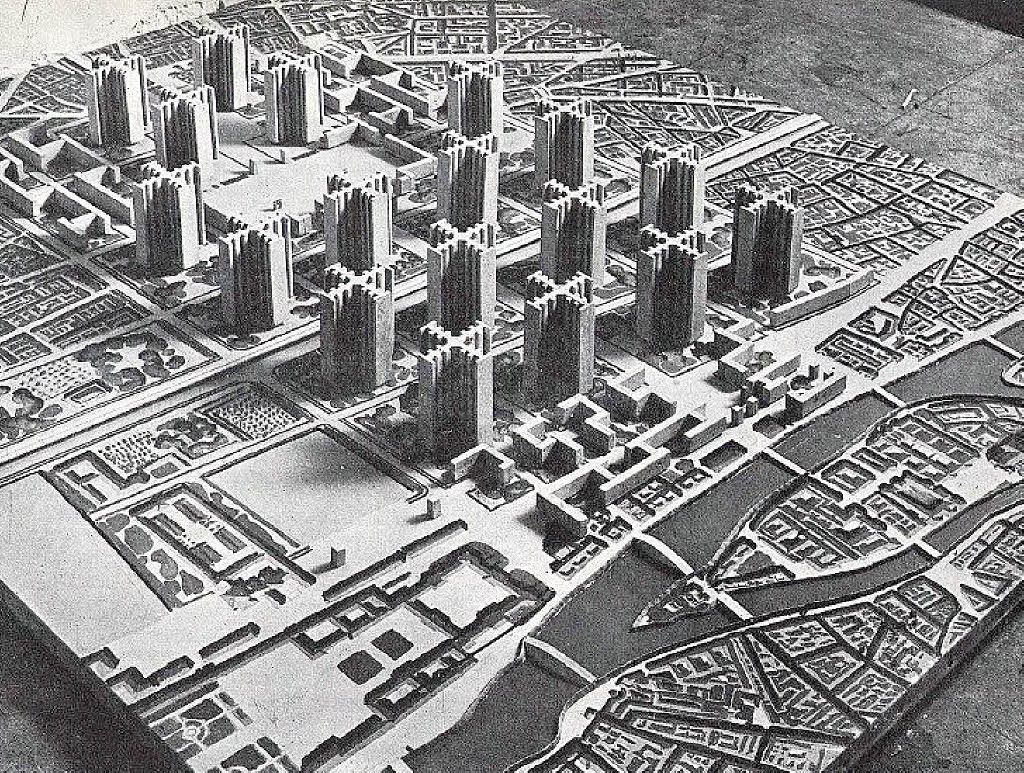

Throughout history, cities have represented everything we, as humankind, have achieved. However, cities are now often identified with certain negative adjectives such as congested, polluted, dreary, etc. Against this background, there is an urgent need to rethink the way cities are planned today and to integrate solutions that not only improve the quality of life for today’s generation but also for generations to come.

A city’s design has a direct impact on the emissions it produces. It has been observed that low-impact cities usually have medium to high-density housing close to centers of commerce and employment; a highly connected street network; a rich mix of land use; accessibility; and low travel distances and times (Winkless, 2022). Moreover, walkable cities have been found to have low emissions and they also avoid the phenomenon of “carbon lock-in”. Carbon lock-in is where efficient and lower carbon alternatives are not added to the transport/energy mix of a city because of self-perpetuating inertia created by large fossil fuel-based energy systems.

This concept can be explained by the concept of cars, which in today’s age define the city life for many. However, cars are not a fact of nature. Cars allow one to transport quickly but are not the only and most efficient mode of transport. Many people feel that way because the infrastructure has been built to accommodate cars (e.g. highways and parking plazas). Moreover, cars have been further reinforced by zoning decisions and urban development patterns. If a city is allowed to grow at low urban density, i.e., houses are far away from commercial and employment opportunities, a car is the only option one has to travel between these distances. This, in conclusion, creates a system where a city is highly dependent on cars; less walkable; and a high emitter.

Big urban centers that are dispersed and auto-centric usually produce more per capita emissions as compared to cities which are high density, compact and walkable cities.

Considering the predicted emission rates and the rate at which reduction is necessary, walkable cities are integral to not only improving the quality of life for citizens but also reducing the overall impact climate change is inevitably going to have.

Benefits of walkable cities

Yes, the current cities are mostly designed around cars but the shift is possible in systematic transformation and decision making. Decision making that prioritizes public transport and increases walkability within neighborhoods can create more walkable cities.

Rebecca Solnit, author of Wanderlust: A history of Walking, wrote, “Walkers are ‘practitioners of the city,’ for the city is made to be walked.” And a city which doesn’t allow walking fails to be a city which could be explored. A walkable city allows for a place that is well-connected with easy accessibility for tourists, residents and students which assists in the revitalization of the economy and the environment.

As per a report published by Silicon Valley, walkable cities allow and increase interaction — an integral ingredient for the economy which is focused on innovation, accessibility and interaction. Moreover, increasing walkability significantly improves air quality as the number of cars is reduced thereby reducing carbon dioxide emissions. Further, walkable cities are also excellent tourist attractions as the city’s attractions are made much more accessible and hardships created by the city’s infrastructure are reduced.

Six Steps to get there:

Step 1: Leaving the highways behind

The highway legacy of the 1950s is a paradigm more difficult to change in less affluent realities. While rich countries dismantle urban highways, many middle- and low-income countries continue to go in the other direction. The negative impact of urban highways is so obvious that most high-income cities have avoided developing them. Seoul, Paris, New York, San Francisco, Utrecht, and Milwaukee were some of these cities that dismantle urban highways. While this is costly, it results in communities that are healthier and more livable. The consequences of this centric-car model are very clear: by cutting off people’s access to walkable networks, urban highways displace people, fracturing communities and furthering segregation. As a result, urban highways sacrifice residential areas to improve traffic flow. But, even if timidly, in some places this culture is beginning to change (ITDP, 2021).

For decades, urban planning, transport planning, and streetscape design in Latin America have been car-oriented. In this regard, car-oriented planning reflects the globalization of automobility, with significant investments in motor vehicles and, in particular, urban highways. Despite this, walking continues to be the most popular mode of transportation in Chile, for example, and Santiago in particular (Herrmann-Lunecke et al., 2020).

Santiago was named the winner of the 2017 International Sustainable Transportation Award for significant improvements in public space, cycling, and public transportation – it had previously been given to cities such as Paris, London, and New York. One good example is the pedestrian-friendly Calle Aillavilú, in the central market of Santiago, which has been turned from a car-congested to a pedestrian-friendly area (ITDP, 2016).

Other public space improvements include 100 square meters of new green space in historic residential neighborhoods, as well as re-designing various areas throughout the city, including the Historical Center’s main streets, which featured a “complete streets” redesign for public transportation exclusive corridors and pedestrianized streets (ITDP, 2016).

Step 2: Change the old patterns of mobility

Step two towards creating a more walkable city is through efficient planning and systematic design and legislative decisions. Our current cities are created around a car-centric mobility system. A system which is not sustainable but also expensive for residents of middle-income countries as the power to purchase cars is quite low in such countries.

How do we change these patterns? By incentivizing public transport systems.

Public transport provides cheaper alternatives to private cars and if such solutions are integrated on a large scale, not only can mobility issues be solved but also lead to fewer emissions which create a more sustainable lifestyle. However, public transport requires substantial government spending and with a system that is already geared towards cars, highways often get prioritized over adding a bus route. However, these patterns can only be changed through persistent planning, prioritization and policy that is geared towards finding long-term solutions.

Step 3: Stop “traffic easing”

In parallel to changing old patterns of mobility, what is needed for city planners and policymakers is to stop traffic easing. As discussed before, our cities have been planned and built around cars and motor vehicles. But cars are not a fact of nature and neither are they the only motor vehicle available for us. Cars, however, are one of the integral factors that drive urban planning in most of our cities. Despite the privacy and abundance of independence offered by cars, these motor vehicles also drive congestion and high emissions within our urban centers.

It is often assumed that adding a lane or increasing roadway capacity will reduce congestion, however, so far, congestion has not improved in any major urban centers solely by adding another lane. What actually happens is that adding another lane allows for more people to drive, thereby doing nothing to reduce the congestion and instead only adding to the total number of cars on the road.

Therefore, where changing urban mobility patterns call for investing in public transport infrastructure, step 3 calls for putting a stop to induced demand. More roads lead to more traffic and do not actually reduce congestion.

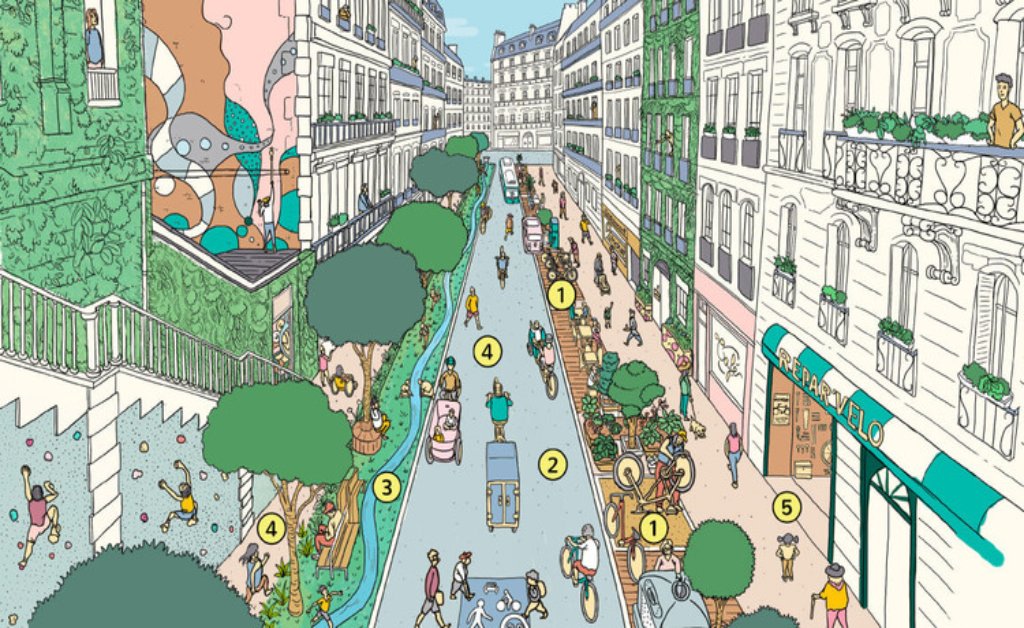

Step 4: Priority streets for pedestrians

Vehicle access is prohibited or severely restricted in pedestrian-priority areas, which prioritize space and safety for walkers and bicycles. This type of street design is commonly used in areas with a high volume of commercial activity and it is common for this to transform the places in areas full of cultural and social events (Yanocha, 2021).

In the city of Curitiba in Brazil, the XV de Novembro Street (Originally known as Rua das Flores) became a social meeting place after being closed to cars in 1972. It was Brazil’s first public road exclusively for pedestrians. In barely 72 hours, the first phase of blocking the roadway to motorists and reopening it to pedestrians was completed. The more than 3 km long pedestrian plaza, which was initially not very popular, is now a prominent gathering location and the core of local businesses in Curitiba’s downtown area. The beginning and foundational concept of Curitiba’s pedestrian orientation may be seen in this human-scale project. It had a significant influence on a city that needed to redesign itself to become more pedestrian-friendly (Agulhon et al., 2015).

In addition to the Brazilian example, a more recent case of street pedestrianization is Burns Road, in Karachi city (Pakistan) which is a linguistic, ethnic, and religious plurality place. It is a renowned food area that has just been declared traffic-free by the government, allowing pedestrians to enjoy the food more comfortably and safely. The change took place in January 2021, when the district administration declared that after 7 p.m., no automobiles would be allowed to enter Burns Road, leaving the nighttime hours to pedestrians only. Burns Road’s pedestrianization has already received good reviews. Improved accessibility by foot has resulted in increased sales, according to food sellers, and also is providing a higher quality public place to those who live or visit the area (Laraib et al., 2021).

Step 5: Using non-motorized transport

In conjugation with Steps 2 & 4, adding non-motorized transport to the overall transport mix of the city, helps reduce emissions and also provides low-cost transport solutions for distances that cannot be covered through walking or quicker access to places. Examples of non-motorized transport include bicycles, electric-assisted bicycles, Mopeds, motor-assisted scooters, and motor-driven cycles. All such mobility devices add very little emissions while providing citizens with fairly quick modes of getting to their destinations.

In fact, cycling as a non-motorized form of transport is quite common in India. As per Heirli, for middle-sized cities in Japan, Germany & Netherlands, at least 40-60% of all trips are made by walking and cycling whereas the number goes up to 80% in India for similarly-sized cities (1993). Further, in many Asian cities, non-motorized two-wheelers and three-wheelers are a common sight. However, most of these NMT users are neglected in the typical urban design process due to it being focused on cars.

A walkable city, specifically within the context of Asian cities, becomes much more viable since the user already exists. What is needed is a dedicated design and urban policy legislation for such users to be provided safety as opposed to cars.

Step 6: Limited Traffic Zones (LTZs)

Limited Traffic Zones (LTZs) are areas that restrict the entry of most vehicles. Furthermore illegal vehicles are subject to severe penalties. Limited traffic zones have proven especially popular in cities with historic centres that were not designed to accommodate high car traffic. Residents, public transportation, emergency vehicles, and frequent taxis are usually allowed and can enter the zone without limitation. Permitted cars are given a permit or placard, or they can lower bollards built around the zone’s boundary to enter. Vehicle volume may be quickly reduced in limited traffic zones, making room for streetscape redesigns that favour walking (Yanocha, 2021).

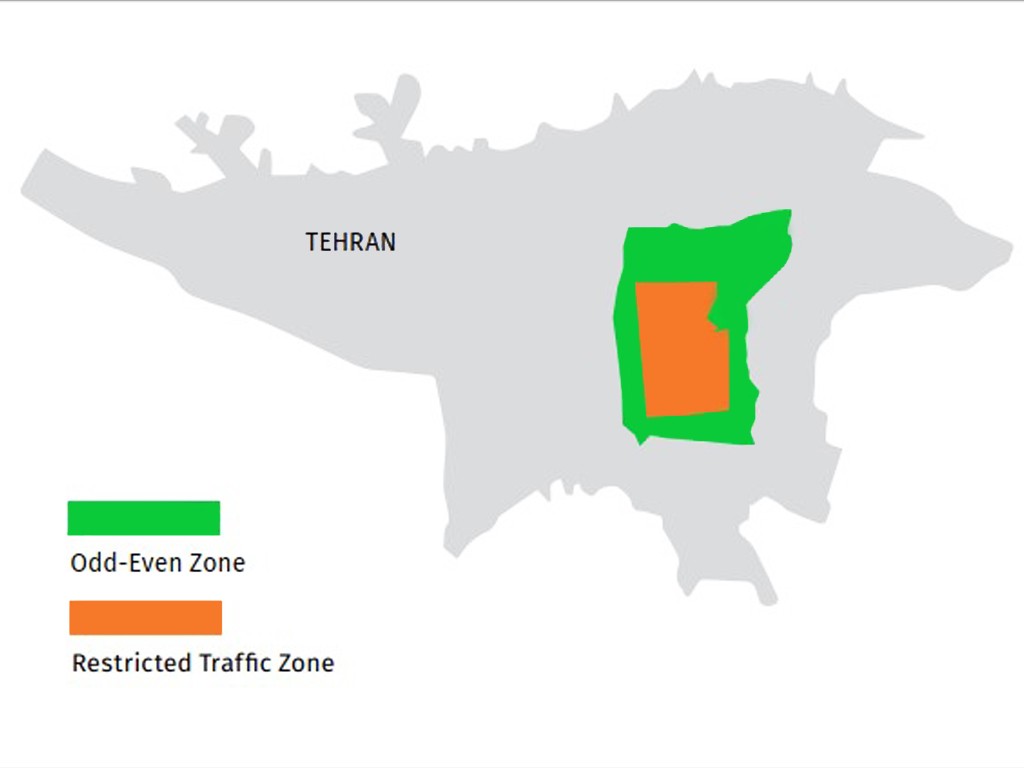

In that sense, measures have been adopted in Iran to regulate the city of Tehran’s (Iran) high vehicle use. There are two downtown traffic zones: the Restricted Traffic Zone (RTZ), which is based on pass authorization, and the Odd-Even Zone (OEZ), which is based on license plate numbers. Both of these areas induce residents to drive less and opt for other kinds of transport (Salarvandian et al., 2017).

And, although there are still no strong public policies in Tehran to combine traffic zones with fast and high-quality walks, Tehran, as well as other cities mentioned in this article, is slowly transforming from an urban car-oriented to an urban people-oriented city. In low-income and lower-middle-income countries, the steps toward walkability are still timid, but it can be expected that high-quality public transport systems in combination with the walkable landscape, high density, and mixed uses are gaining importance.

About the Author 1

Tiffany Nicoli is a researcher and holds a Master’s in Architecture and Urban Planning at the Federal University of Viçosa, Brazil. She is enthusiastic about active urban mobility and passionate about urban design. She feels that social exchanges inspire her to think about possible and more human cities. She enjoys walking and cycling and is always excited to study and discover new cities.

About the Author 2

Arooma Naqvi is an aspiring urban researcher with a bachelor’s in Social Development & Policy from Habib University, Pakistan. She is passionate about creating sustainable cities through effective design and policymaking. She has previously worked in areas of climate and sustainable development and aspires to gain specialisation in the fields with a focus on urban planning.

Related articles

Rethinking Urban Planning Careers in India

AI Urbanism: Utopia or Dystopia? The Unvarnished Truth.

5-Days UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

14th-18th July 2025

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “