Decolonizing Urban Planning: Towards Pluriversal and Inclusive City-Making

Urban planning has historically been dominated by Western-centric models prioritizing order, standardization, and top-down control. While these frameworks provided infrastructure and modernization in many cities, they often ignored local cultures, knowledge systems, and spatial practices. This article explores alternative approaches through the lenses of decolonizing urbanism and pluriversal design.

Decolonizing urbanism calls for reevaluating inherited planning models and placing marginalized voices at the center of decision-making. It emphasizes local engagement, social inclusion, and recognition of diverse ways of organizing urban space. Pluriversal design complements this by promoting culturally rooted and ecologically sensitive practices over one-size-fits-all solutions.

The article also examines tools that support these approaches, such as participatory planning, tactical urbanism, and digital platforms. These methods allow communities to actively shape their environments, fostering shared ownership and more adaptable outcomes.

Western-Centric Urban Planning and Its Critique

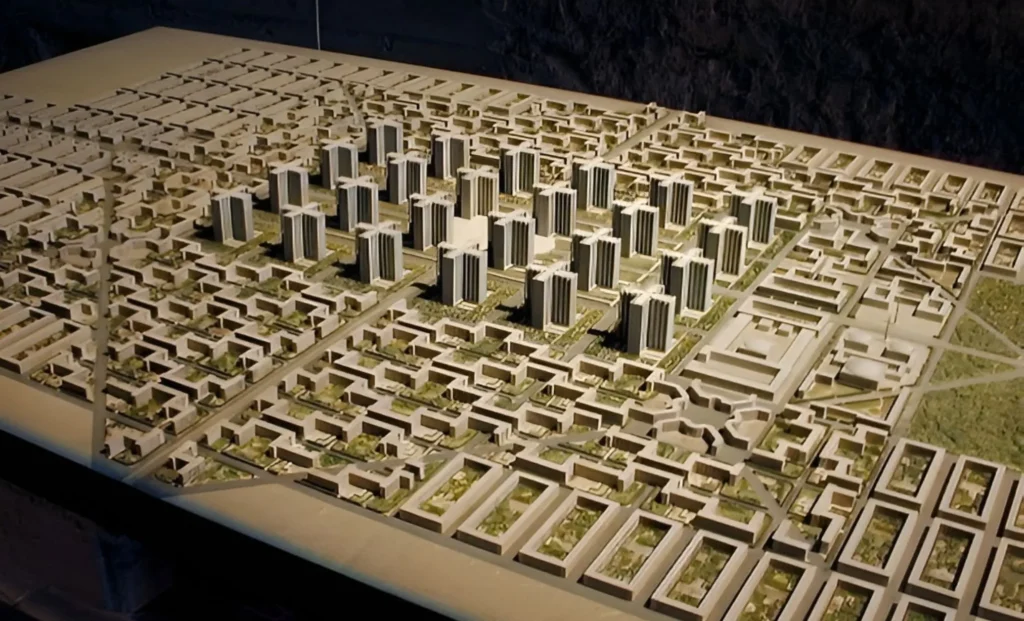

Urban planning emerged in Western industrial societies, emphasizing master plans, rigid zoning, and modernist ideals that assumed universal relevance. Influential models like Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City and Le Corbusier’s Radiant City reflected faith in rational layouts and centralized control. These approaches, spread globally through colonization and modernization, improved infrastructure and sanitation based on Western norms. However, applying such models across diverse contexts often led to challenges. Critics argue that top-down, uniform planning frequently disregards local cultures, informal settlements, and social networks sometimes displacing communities or reinforcing exclusion. Universalist plans tended to marginalize alternative ways of organizing space. Over time, urban theorists began to question the Eurocentric assumptions embedded in planning history and practice. The aim is not to dismiss Western contributions, but to move beyond their uncritical adoption. This has led to more inclusive and flexible planning approaches that prioritize local needs, cultural identities, and grassroots participation encouraging cities to develop in ways that reflect their own unique contexts.

Decolonizing Urbanism

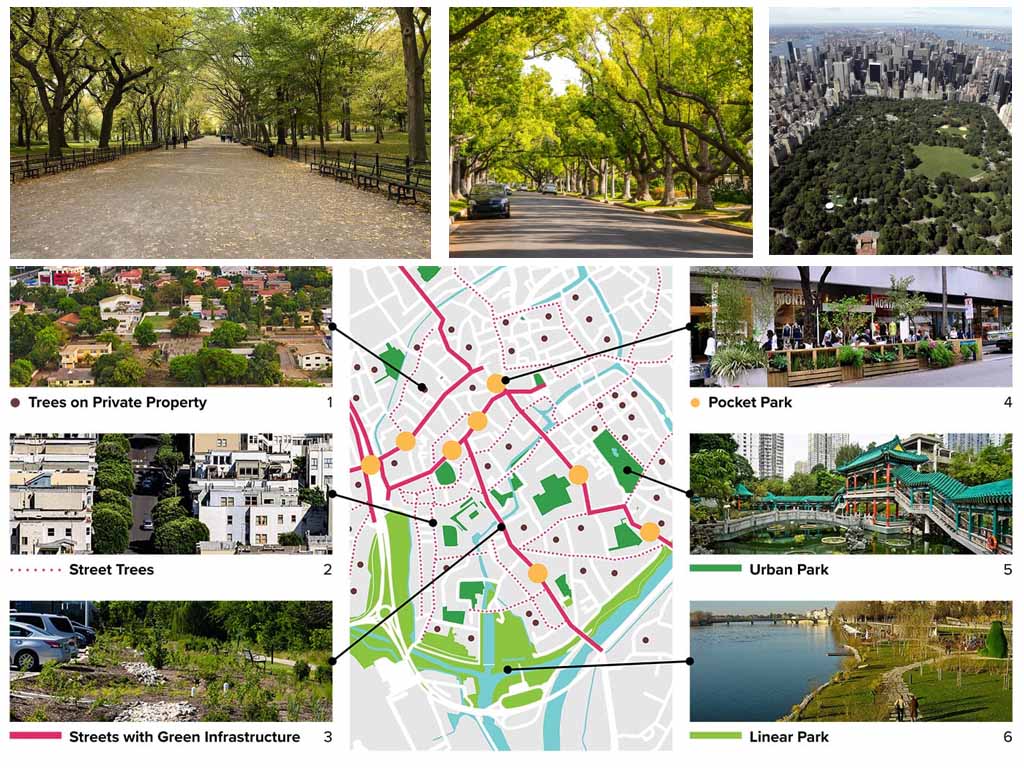

Decolonizing urbanism emphasizes the importance of reshaping cities by re-evaluating how past decisions influenced current urban structures. It encourages planners to move beyond externally imposed models and consider historically rooted, locally appropriate alternatives. Many cities around the world reflect a legacy of imported planning ideas whether colonial, imperial, or technocratic that shaped zoning, building typologies, and infrastructure priorities. While these models brought a degree of order and modernization, they often failed to reflect the lived realities of local populations.

Decolonizing urbanism involves acknowledging these historical imprints and reorienting planning practice around inclusive values. This includes amplifying marginalized voices in decision-making, prioritizing public space that supports everyday social life, and adapting urban forms to reflect cultural specificity. Rather than treating cities as blank slates to be “rationalized,” this approach values their complexity and memory. It also embraces interdisciplinary insights from sociology, anthropology, and environmental studies to better understand how different communities relate to space. Ultimately, decolonizing urbanism is not a rejection of all formal planning, but a call to rethink who plans, for whom, and based on what knowledge systems.

Source: Website Link

Pluriversal Design: A Philosophy of Many Worlds

Pluriversal design promotes the idea that urban planning should accommodate a variety of cultural perspectives, practices, and knowledge systems. Rooted in the concept of the “pluriverse,” it opposes the notion of a single, universal design approach that fits all cities. Instead, it recognizes that different communities have unique ways of organizing, building, and living in space, and that these differences should inform planning and design decisions.

Unlike traditional models that prioritize uniformity, pluriversal design supports culturally embedded solutions. For example, a coastal town may integrate design practices based on marine ecology and local rituals, while a mountain community may prioritize thermal adaptation and seasonal settlement patterns. This design philosophy encourages collaboration with residents, rather than imposing top-down interventions, and values lived experience alongside technical expertise.

Pluriversal design aligns with sustainability goals by adapting to climate and cultural realities. It broadens the design imagination to include marginalized perspectives, ensuring that city-making is not about producing one homogenous “global city,” but about nurturing the diverse lifeways of people in their own places. By integrating multiple rationalities scientific, spiritual, communal, experiential pluriversal design offers a pathway to more adaptable and inclusive urban futures that respect context over cookie-cutter solutions.

Tools for Resistance and Inclusion in Planning

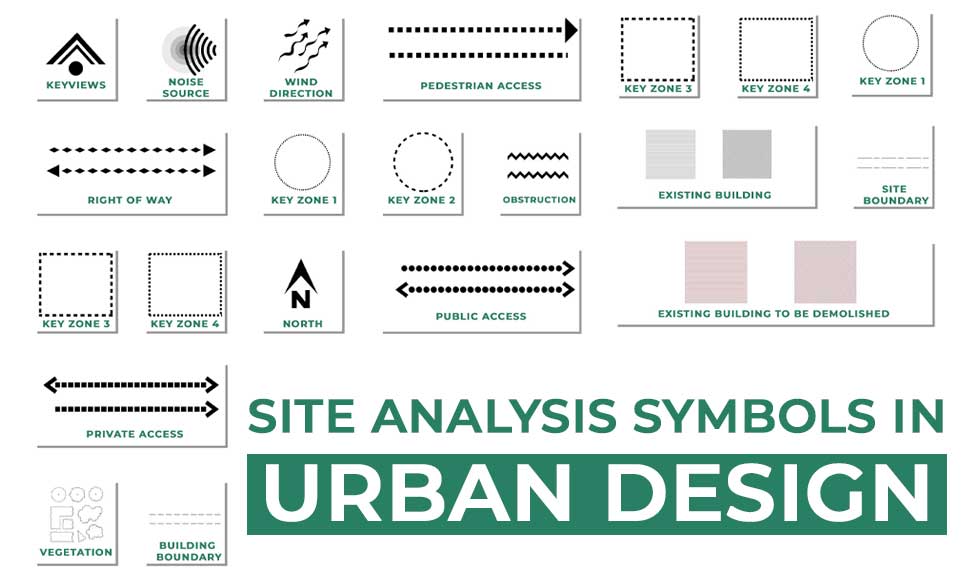

To implement inclusive planning principles, many cities now use participatory and adaptive methods that invite local input and test solutions in real time. One key approach is participatory planning, which involves residents in shaping development projects through workshops, surveys, or collaborative design sessions. This builds trust and ensures that plans reflect daily realities and community values.

Tactical urbanism offers another tool by encouraging temporary, low-cost changes in public space. These can include pop-up parks, experimental pedestrian zones, or pilot bicycle lanes that show how space can be reimagined before permanent investment. Because they are small and reversible, such actions allow feedback and flexibility while promoting citizen agency.

Digital engagement tools

Digital engagement tools also play a growing role. Online platforms enable residents to participate in planning by voting on proposals or adding location-based comments. Map-based surveys and interactive forums allow planners to gather insights directly from the public, broadening engagement beyond formal meetings.

Grassroots and community-led initiatives

Grassroots and community-led initiatives complement these tools by allowing local actors to organize and address needs through informal means. Community gardens, neighborhood clean-ups, or self-managed housing projects illustrate how urban transformation can emerge from below. While small in scale, such efforts often influence policy and contribute to a more democratic planning culture.

Conclusion

Cities around the world are shaped by layered histories, diverse populations, and evolving needs. As planning continues to respond to global and local challenges, the integration of decolonial thinking and pluriversal design offers new directions. By revisiting the past not to discard it, but to better understand it planners and communities can create frameworks that are more inclusive and adaptive.

Efforts to bridge planning gaps are increasingly visible through participatory projects and culturally sensitive approaches. These methods show how cities can shift from inherited templates toward practices that reflect their unique identities and community needs.

The future of urban planning lies in co-creation, dialogue, and openness to multiple perspectives. By blending professional expertise with local knowledge, and long-term planning with short-term experimentation, cities can become more resilient, equitable, and meaningful for their residents. Inclusive city-making is not a fixed goal, but a continuous process of learning, adjustment, and collaboration.

References

- Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A Ladder of Citizen Participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224.

- Escobar, A. (2018). Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Duke University Press.

- Porter, L. (2010). Unlearning the Colonial Cultures of Planning. Ashgate.

- Robinson, J. (2006). Ordinary Cities: Between Modernity and Development. Routledge.

- Watson, V. (2009). ‘The planned city sweeps the poor away…’: Urban planning and 21st-century urbanisation. Progress in Planning, 72(3), 151–193.

- Finn, D. (2014). DIY urbanism: Implications for cities. Journal of Urbanism, 7(4), 381–398.

- Sabhlok, A., Mhatre, A., & Swamy, S. (2021). Pluriversal Design and Decolonial Praxis. In Design Philosophy Papers, 19(1), 77–94.

Gizem Fatma Mermer

About the Author

Urban Planner | Visual Communication Specialist | Media Analyst

Gizem is a trained urban planner with over a decade of experience in media and visual communication. She has worked in national broadcasting as a graphic designer, supervisor, and analyst, building expertise in data visualization, audience research, and strategic storytelling.

Related articles

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “