15-Minute City: A vision for the future?

The unprecedented COVID-19 health crisis has exposed the cities’ fragilities and the need for urgent responses facing global urban shock. In this sense, it is possible to mention two key aspects that required rapid transformation and adaptation: urban displacement and public space usage. For contexts in which this was possible, work was adapted to the home office, making us reflect on the time lost in commuting to the workplace. In addition to the restriction on travel and advice to stay at home, one of the essential recommendations of the WHO (World Health Organization) to contain the advance of the pandemic was to maintain a minimal physical distance, which directed efforts to standardize the use of public space. We, therefore, realize the importance of having easy access to urban services and how much our neighborhoods lack urban amenities at a local level. In this context, in which the neighborhood scale becomes the possible dimension to carry out essential activities, the 15-Minute City model prospers and leads authorities and governance to adopt urban planning mechanisms that aim to fill the collective sphere more closely, in both physical and social way.

The 15-Minute City model encompasses climate action and people-centered urban development initiatives to create an approach that can help cities of all shapes and sizes better cope with and recover from the pandemic. This model describes an aspiration for more vibrant, integrated, connected, and equitable areas. Among other things, it means strengthening local centralities, transit connections with the rest of the city, with the area, and relationships between residents, all from a short walk or bike ride close to home.

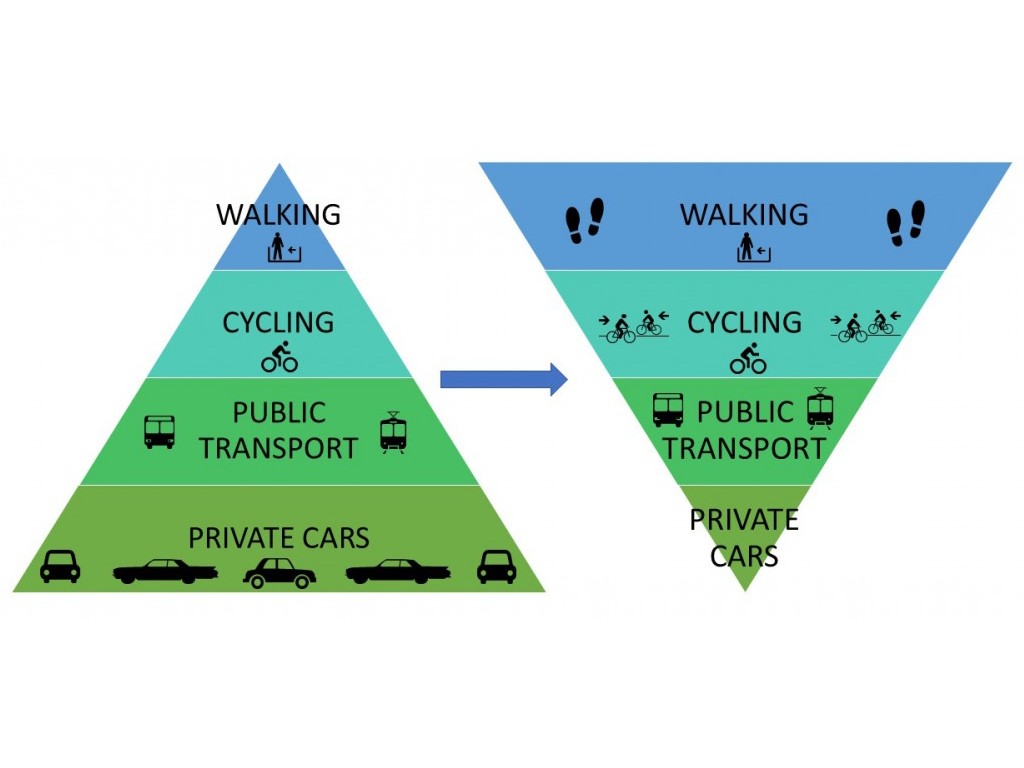

There is increased awareness of the importance of active transport options and green spaces in the COVID-19 pandemic context. That way, new community centralities are increasingly needed once we are heading towards a post-pandemic moment. And “walking” – in the literal sense of the word – since by adopting the neighborhood scale and smaller distances in the routine, many people adhered more intensely to the most common active ways to move: walking or cycling. Still, this option of moving through active modes requires a more significant effort on the part of municipal governments in delivering the necessary infrastructure to sustain these displacements and, at the same time, integrated and effective urban planning.

The 15-Minute City concept

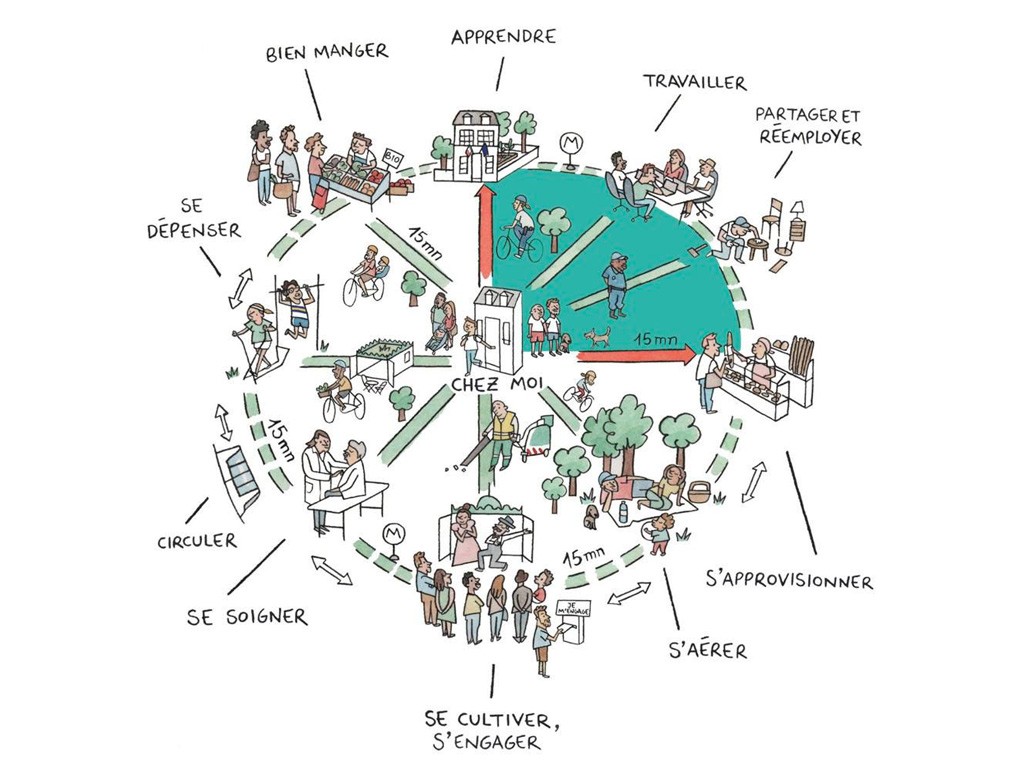

The term “15-minute city” (ville de quart d’heure) was coined in 2016 by the Sorbonne (Université de Paris) professor Carlos Moreno. This idea was later popularized by the current mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, who won her second term defending this model. Moreno presents the concept as a new paradigm to promote more sustainable cities with good quality of life based on “hyper-proximities” based on four major components: proximity, diversity, density, and ubiquity. This concept proposes a social, environmental, and urban reconfiguration for neighborhoods, making them more accessible to essential social functions, allied to the defense of a compact city. According to Carlos Moreno, in 15 minutes, on foot and/or by bike, citizens can enjoy at the same time social and geographical proximity if the following urban social functions can be reached within a short perimeter: living, working, supplying, caring, learning, and enjoying.

As workplaces, shops, and homes get closer, the street space that used to be dedicated to cars is converted into people-oriented spaces, contributing to the reduction of atmospheric pollution generated from the automotive matrix. This makes way for squares, parks, boardwalks, bike paths, sports facilities, and green and leisure areas.

Despite the variety of discourses, ideas similar to these have existed for a long period of time in the history of urban planning, in which successes and failures of ideal city projects indicated the vicinity as a place that residents turn to meet their basic needs, interact, and communicate. In addition, several cities were already implementing 15-minute strategies before the pandemic, but interest has increased since the virus started local outbreaks and put people’s safety at risk.

The 15-Minute City paradigm now represents a significant shift in the global race for more sustainable cities. Emboldened by the pandemic, mayors worldwide are now directing their efforts to reshape their cities and keep up with the trend towards a slower pace of life. As cities emerge from the worst of the COVID-19 crisis, the 15-Minute City approach offers a way to provide more walkable, cyclist-friendly, and inviting places to stay.

As well as the Paris 15-Minute City that captured international attention in the wake of the pandemic, here are some cities that are important examples of implementing the urban model that can be covered in a few minutes; each one with its own singular approach: Melbourne’s 20 Minute Neighborhoods, Portland’s Complete Neighborhoods, and Bogotá’s Barrios Vitales. Despite the different widespread nomenclatures and the particular implementation processes – mainly due to the influence of urban matrices, sometimes compact, sometimes dispersed – these cities share a global trend focused on returning to a local way of life and a more friendly urban experience in short circuits.

1. Melbourne’s 20-Min Neighborhoods

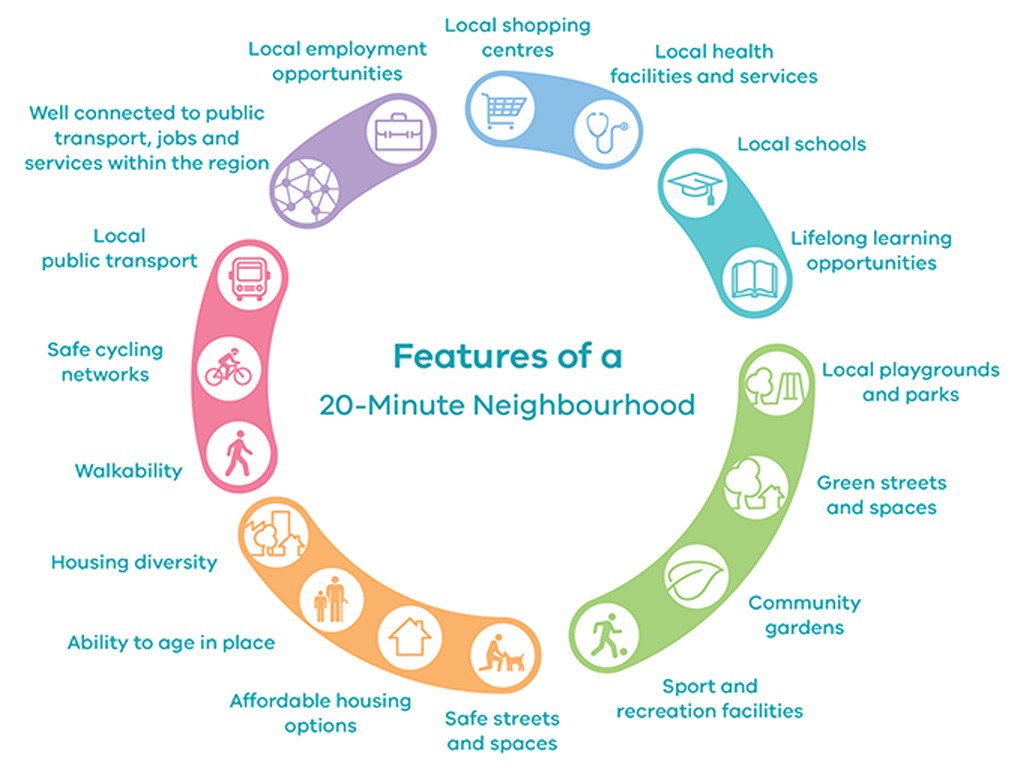

Like Paris, Melbourne (Australia) has created its own version of a possible city in a short space and time, with neighborhoods where everything is accessible within a 20-minute commute. Since 2017 the Melbourne government has focused on long-term urban planning, with horizons up to 2050 (Plan Melbourne 2017–2050) and in line with the idea of “20-Minutes Neighborhoods”.

The idea is basically the same: 20-Minute Neighborhoods celebrate the reduction of dependence on the private car when they can provide walkable streets and avenues, safe cycle paths, and quick and easy access to public transport. Furthermore, these locations promise to spread the culture of consuming locally within the district’s perimeter, which helps to move the local economy. Other positive factors are the improvement in the residents’ health, provided by a more active lifestyle; a significant increase in connections and social exchanges within communities; and a significant contribution to combating climate change.

In this case, while the city’s aspirations are similar to those of Paris, the issues involved in implementing them are particular, as Melbourne’s urban development pattern has been shaped by car-oriented policies. One big difference is that Paris has a well-developed transit system and adequate urban density for an environment that is highly accessible on foot or by bicycle. Meanwhile, in Melbourne, there are still regions that are “transport deserts” and where the jobs density is still lower when compared to inner-city areas.

If the density is an essential factor in implementing the concept in a short space and time in a city, it is correct to think that neighborhoods well prepared for this idea are populous and diverse places, which have both a variety of services and good connections with public transport. However, in Melbourne, some suburbs away from the center have very low density, and their public transport supply is insufficient to support the initiative. Also, given Melbourne’s extensive development type, public transport may only be viable for some areas. Even so, government and citizens are betting on local networks and the insertion of 20-Minute Neighborhoods, which became essential strategies for urban transition to a high-quality social life.

2. Portland’s Complete Neighborhoods

North American cities, defined over time by a highway culture logic, are similarly optimistic and increasingly exploring the city in a few minutes – especially with lessons learned and self-reflection during the COVID-19 pandemic. In urban contexts in which people are used to spending more than an hour a day commuting to work in private cars, a new focus emerges, which is to return the streets to people in “complete neighborhoods” whose logic aims to a city of inclusive, healthy and vibrant neighborhoods, promoters of connection and sociability. In this case, local public space and social exchanges are essential and stand out in the planning of global managers, as is the case of Portland in the United States of America.

The City of Portland is celebrated by many city planners as a new paradigm for US urban planning. Maybe this is because Portland has the highest bicycle commuting rate of any major North American urban center, and its residents don’t have to travel long distances to work, shop, or play. Currently, the Department of Transport is investing massively in large infrastructure for bikes and free pedestrian traffic, as well as public transport, ensuring connections between centralities.

The proposal is ambitious and clear: according to the “Portland Climate Action Plan”, drawn up in 2015, it was established as a goal for the “complete neighborhood” that by the year 2030, 80% of residents would be able to access all their basic needs daily, effortlessly, on foot or by bicycle, and with safe and favorable displacement through the city streets.

3. Bogotá’s Barrios Vitales

The South American City of Bogotá, the capital of Colombia, also invested in an ambitious approach to promote sustainable urbanity and mobility in a short space and time during the pandemic. The return of a human-centered approach to urban planning with vibrant, friendly neighborhoods connected by high-quality public transport and cycling infrastructure are also common principles for the “Barrios Vitales”.

Bogotá’s Barrios Vitales (Vital Neighborhoods) are based on deprioritizing private motorized transport to redistribute the citys’ street space in favor of those who walk, cycle, or enjoy the local commerce and culture. It proposes a network of green corridors and prioritizes streets for cyclists using restrictions and traffic calming resources, in addition to an urban redesign to create people-centered mobility and re-qualify public spaces.

During the pandemic, Bogotá has injected more life into local areas across the city: it was installed bike racks at bus and subway terminals and created cycle lanes to encourage cycling. After the beginning of distancing measures in 2020, the city government implemented around 117 km of temporary cycle lanes to encourage pedaling to reduce the risks of coronavirus contagion in public transport, in addition to promoting cycling. A good part of these temporary cycle lanes became permanent, now integrating the largest network of cycle paths in Latin America, with a total of 344 kilometers, one of the largest cycle networks in the world.

A city in 15 minutes also means ensuring that activities that make urban life more liveable and enjoyable are available to everyone through participatory processes. In the “Barrios Vitales” project, citizens are encouraged to offer ideas and suggestions to the public authorities to improve their neighborhoods. The options are endless: improving road safety, reactivating local businesses, promoting cultural events, or whatever residents feel important to keep their districts active and vibrant. That’s why the 15-Minute City view is also a decentralized space that allows people to reconnect with their neighborhoods and communities.

Through active and sustainable mobility practices, such as those in Bogotá, the 15-Minute City model has increased accessibility to basic resources and services, including improving the quality of life for marginalized communities. Proximity to resources and services is a key element of the 15-Minute City, as well as a strengthened, equitable urban policy, which offers a variety of opportunities to diverse social strata, with easy reach and short distances.

The future of the 15-minute planning model

As cities emerge from the sanitary crisis, the 15-minute approach offers ways to deliver that change: a boost to the local economy, more equitable public spaces, better physical and mental health, increased quality of life, and local well-being. Moreover, these cities also experience a drastic reduction in air pollution from the removal of unnecessary travel by private cars that would dump tons of pollutants into the atmosphere.

The concept of a 15-Minute City is in sharp contrast to the paradigms of highway culture in urban planning that dominated the last century based on rationality, segregation, and car-centric urbanism. Still, many of the ideas and principles underpinning the 15-Minute City model are not new. Instead, what is new and distinctive is integrating a core set of ideas and principles for people-centered and people-shaped urban development.

We know that humanizing cities is urgent. But genuinely connecting and integrating their regions is much more than just remodeling their streets; it demands investing in the human first. Individuals must choose to walk and/or cycle; this must be a choice, and for this to really be an option, accessibility is critical. While currently, only a few neighborhoods are highly walkable or bike-friendly in major cities worldwide, many more are likely to move in this direction, shaping the city of the future, traversed in minutes, and experienced by all.

About the Author

Tiffany Nicoli is a researcher and holds a Master’s in Architecture and Urban Planning at the Federal University of Viçosa, Brazil. She is enthusiastic about active urban mobility and passionate about urban design. She feels that social exchanges inspire her to think about possible and more human cities. She enjoys walking and cycling and is always excited to study and discover new cities.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “

One Comment