Book Review: Walkable City by Jeff Speck

Jeff Speck’s book, Walkable City: How Downtown Can Save America, One Step at a Time, is an important contribution to urban planning. It argues for making American cities more pedestrian-friendly. Speck, with his background as a city planner, presents complex ideas in an easy-to-understand way. He believes that walkability is essential for vibrant cities, which is increasingly relevant as people focus on sustainable living.

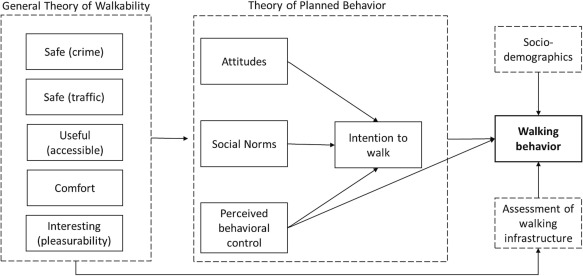

Speck introduces the “General Theory of Walkability,” identifying four key elements: useful, safe, comfortable, and interesting walking environments. While he provides useful examples and case studies, some critics feel the book could use more solid data to back up his claims.

The ten steps to achieve walkability offer practical advice for city planners. However, some argue these solutions might be too simplistic for the complex nature of American cities. Speck’s engaging writing style combines humor with analysis, making the book enjoyable. Despite relying mostly on existing research, Walkable City is a valuable resource for those in urban planning. It emphasizes the importance of walkability and encourages future research to explore its impacts more deeply.

Introduction : Walkability is a key to Urban Vitality

Jeff Speck’s book, “Walkable City: How Downtown Can Save America, One Step at a Time,” stands out as a crucial contribution to urban planning discourse. It offers a persuasive case for reshaping American cities to prioritize pedestrians. Throughout the text, Speck draws on his extensive background as a city planner and designer, blending years of urbanist ideas into a narrative that is both engaging and straightforward. The central idea—that creating walkable spaces is essential for vibrant urban life—resonates strongly today, particularly in light of the increasing focus on sustainability and quality of life in urban environments. Despite the strength of Speck’s arguments and the clarity of his presentation, some critics point out limitations in his research approach and the level of empirical evidence provided. This can be a concern for scholars who expect thorough, data-driven evaluations in their studies of urban development. Speck’s work invites important conversations about the future of urban living and the role of walkability in achieving it.

The General Theory of Walkability

Speck’s argument is anchored in what he terms the “General Theory of Walkability,” which asserts that urban areas flourish when they are designed to promote pedestrian activity. He outlines four essential elements for walkability: functional, secure, pleasant, and engaging walking spaces. These elements are detailed through a combination of personal stories, illustrative case studies, and urban principles. For example, Speck demonstrates the financial advantages of walkable urban areas by referencing research that connects walkability to increased real estate values and higher local expenditures. He also underscores health and ecological advantages, citing studies on diminished obesity rates and reduced greenhouse gas emissions in walkable neighborhoods. While these arguments are persuasive, the text could improve with a more thorough examination of quantitative evidence to further validate these assertions.

Source: Website Link

Practical Steps to Achieve Walkability

The ten strategies for achieving walkability constitute the essential framework of the book, providing an extensive guide for urban developers and decision-makers. These strategies include decreasing reliance on automobiles, enhancing public transportation, improving pedestrian safety, and incorporating greenery to create more attractive streetscapes. Speck’s systematic method is both practical and forward-thinking, making intricate urban design concepts understandable to a wide audience. Nonetheless, some reviewers might contend that his recommendations, while creative, could be too simplistic when applied to the varied and often complicated political context of American cities. The book sometimes overlooks the difficulties of enacting such transformations, especially in areas with deeply rooted car-oriented habits.

Here are the ten strategies for achieving walkability as described in Walkable City by Jeff Speck:

- Put cars in their place: Prioritize pedestrians and cyclists over cars in urban planning to create more inviting spaces.

- Mix the uses: Encourage a blend of residential, commercial, and recreational spaces to enhance accessibility and promote vibrant communities.

- Get the parking right: Optimize parking solutions, including reducing parking requirements and utilizing shared parking to enhance walkability.

- Let transit work: Improve public transportation options to connect neighborhoods effectively and reduce reliance on personal vehicles.

- Protect the pedestrian: Implement measures to ensure pedestrian safety, such as improved crosswalks, traffic calming measures, and well-designed streets.

- Welcome bikes: Create dedicated bike lanes and infrastructure to promote cycling as a viable and safe mode of transportation.

- Make friendly and unique faces: Design buildings with engaging facades that encourage pedestrian interaction and contribute to a lively streetscape.

- Plant trees: Increase greenery and tree canopies in urban areas to improve aesthetics, provide shade, and enhance the walking experience.

- Pick your winners: Identify and focus on key streets that can be transformed into pedestrian-friendly corridors, serving as models for broader urban improvements.

- Build more homes: Increase the availability of diverse housing options to support walkable neighborhoods and reduce sprawl.

Speck's Writing Style

A notable advantage of “Walkable City” is Speck’s captivating writing style. He skillfully merges humor and cleverness with thoughtful analysis, making the book a pleasurable experience. His incorporation of anecdotes and personal insights introduces a relatable element to the conversation, demonstrating abstract ideas with tangible examples. For example, his commentary on oversized emergency vehicles influencing street design in Miami offers a witty yet significant critique of the peculiarities of contemporary urban planning. While the narratives are engaging, they can seem more anecdotal than representative of wider patterns or backed by substantial data.

Research Methodology and Evidence

Regarding research methods, “Walkable City” largely depends on secondary data and case analyses. Speck references a variety of urban planning texts, including works by Jane Jacobs and Jan Gehl, to bolster his claims. He also cites numerous reports and studies to underscore the advantages of walkability. However, the book does not include primary research or empirical investigations conducted by the author. This dependence on pre-existing literature means that while Speck’s integration is perceptive, it does not offer innovative contributions in terms of original research. For academics and professionals looking for fresh empirical findings, this may be viewed as a drawback.

Contribution to Urban Planning

The impact of “Walkable City” on the realm of urban planning is considerable, especially in its capacity to convey intricate concepts to a wider audience. Speck’s promotion of walkability resonates with modern movements in urbanism that emphasize sustainability, public health, and social equity. The book acts as an important reference for urban planners, designers, and policymakers, offering both a vision and practical strategies for developing more livable communities. However, for scholarly readers, the book’s absence of methodological depth and original investigation may restrict its effectiveness as an academic reference. Subsequent research could expand on Speck’s findings by performing longitudinal analyses of the effects of walkability projects or examining the sociopolitical factors involved in implementing walkability across various urban environments.

Emerging Trends and Innovative Approaches

“Walkable City” also emphasizes new trends and creative strategies in urban planning. Speck’s focus on mixed-use development, for instance, mirrors a wider transition towards more integrated, multifunctional urban environments. His promotion of decreasing automobile reliance aligns with international movements advocating for more sustainable transportation methods. Additionally, Speck’s exploration of “walkability dividends”—the economic, health, and ecological advantages of walkable areas—demonstrates a comprehensive perspective on urban design that takes various aspects of city life into account. These trends reflect an increasing acknowledgment of the interconnected nature of urban systems and the necessity for thorough, interdisciplinary approaches to urban issues.

Conclusion

To conclude, “Walkable City” is an insightful and impactful text that effectively argues for the advantages of walkable urban spaces. Speck’s claims are persuasive, and his actionable suggestions offer a useful resource for urban planners and decision-makers. However, the book’s dependence on secondary materials and anecdotal evidence means that it lacks the empirical strength and original investigation required to fully engage academic readers. Despite these shortcomings, “Walkable City” makes a meaningful impact on the discipline by emphasizing the significance of walkability and providing a clear framework for creating more livable, sustainable communities. Future studies should expand on Speck’s observations, investigating the intricate dynamics of urban change and supplying solid empirical support for the case for walkable cities.

References

Speck, Jeff. Walkable City: How Downtown Can Save America, One Step at a Time. North Point Press, 2012.

Sreetama Roy

About the Author

Sreetama Roy is a final-year undergraduate architecture student at Sister Nivedita University in Kolkata, specializing in urban design. Her research interests focus on the interplay between urban environments and human activity, aiming to create spaces that resonate with users’ needs. As she trains to become an architect, Sreetama engages in sketching and exploring contemporary media, to enrich her creative process and understanding of design

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “