Tactical Urbanism: Antecedents and contemporary applications

Designing cities for people, not cars, is the motivation behind many Tactical Urbanism projects. And due to the main trends in urbanism in recent decades, we are currently evolving toward a more human-centered idea of urban planning.

What is Tactical Urbanism?

Popularized in the 21st century, Tactical Urbanism can be seen as a way of intervening in space. Because it is not a unified movement, there are several ways of doing it, encompassing a range of comprehensive and different projects, which are usually also particular to each other and each place. Therefore, the opportunities for applying this approach in the public space of cities are numerous. It can be a parklet, the construction of a square or a community garden, the widening of the sidewalk, the closing of a street, or a painting on the floor, transforming the urban design to favor the people. The main characteristic is that they are short-term and low-cost actions that aim at a horizon of changes much more significant than their physical prototype and propose possibilities for long-term transformation in cities. (Sansão-Fontes et al., 2020).

The movement gained strength in the context of a crisis in urban areas, and its actions are usually associated with attempts to respond to urgent problems of everyday life in which governments face difficulties in delivering basic urban services, such as housing, transport, and public space (Brenner, 2016). Most of the time, it is a concept that promotes a participatory vision of urban restructuring, which involves different actors, including governments, businesses and nonprofits, citizen groups, and individuals. “For citizens, it allows the immediate reclamation, redesign, or reprogramming of public space. For developers or entrepreneurs, it provides a means of collecting design intelligence from the market they intend to serve. For advocacy organizations, it is a way to show what is possible to garner public and political support. And for government, it´s a way to put best practices into, well, practice – and quickly!” (Lydon and Garcia, 2015:3).

Some antecedents and contemporary applications of Tactical Urbanism

Tactical Urbanism is not a new idea for cities. The impulse to occupy public space in a temporary way (sanctioned or not) has existed since the emergence of cities, whether through rituals of commerce, politics, recreation, or art. Historical precedents demonstrate that we are always looking to adapt the urban environment more creatively and more efficiently to enhance urban living. In contemporaneity, creating cities for people has become an infinitely more complex effort since the introduction of many transportation modes (Lydon and Garcia, 2015).

The following are some historical precedents of Tactical Urbanism and some of its reflexes in contemporaneity, and examples of application. Actions that can help and inspire us to think of safer, more active, walkable, accessible cities, more public than private, more friendly to social encounters and exchanges, more community, vibrant and humane. Cities designed for and by people.

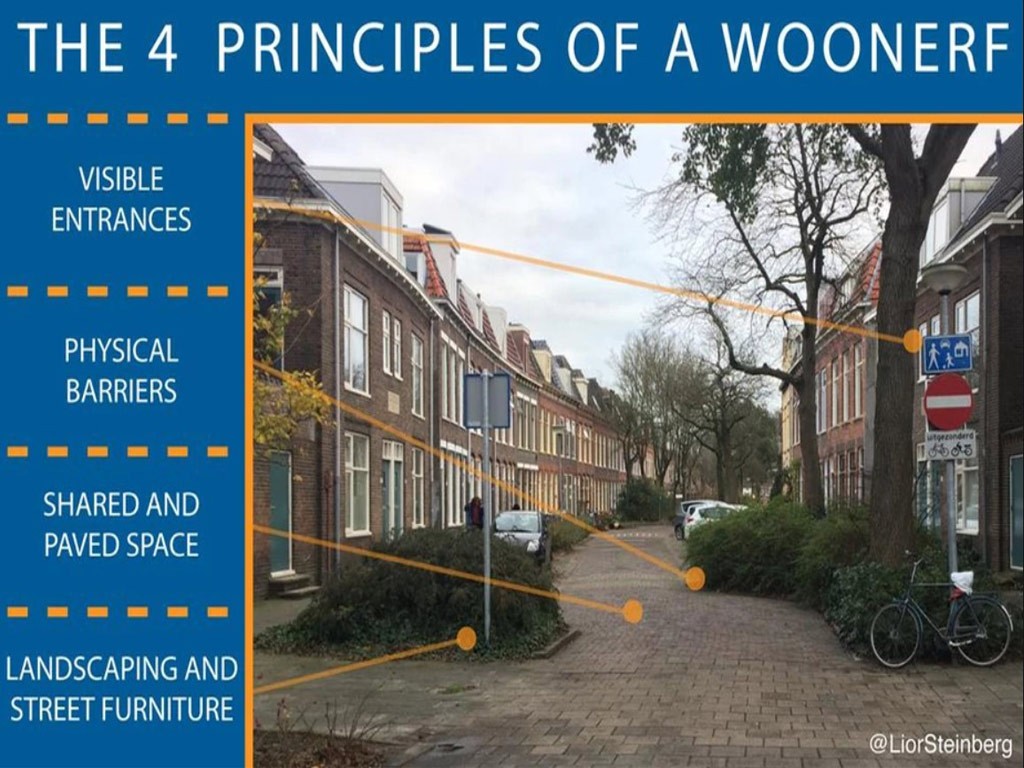

1- Woonerf

The Dutch word Woonerf (plural Woonerven) literally can be translated to “Living Yard”. The concept is common in other countries by different names; for example, in the United Kingdom, they call it “Living Streets” and in Hebrew, “Rechov Hollandi” (Dutch Street). It’s a residential street where people who are not in cars are given priority over people who are. Pedestrians share the street with vehicles, which must follow the pace of pedestrians (Steinberg, 2015). In addition, this street typology eliminates control devices as much as possible, keeping the minimum of signaling or traffic lights, which also minimizes the impact of the car and traffic in places close to residential areas (Dérive LAB e SampaPé, 2017).

This idea emerged in the Netherlands, at the end of the 60s, through a popular initiative in the city of Delft. People literally occupied or reclaimed the street, so to speak. The concept was attributed to a group of neighbors who, concerned about high speeds, took it upon themselves to slow traffic in their neighborhood. In addition to cars, the Dutch Woonerf is a street that accommodates pedestrians, bicycles, and people recreating. Furthermore, the Woonerf exemplifies the significance of allowing bottom-up initiatives to guide top-down processes (Lydon and Garcia, 2015).

The Dutch traffic authorities have noticed the positive results on a local scale, and the design of most of the predominantly residential streets has changed. The transit department focused its attention not on technical factors and the automobile but looked at human behavior. This Citizen-led, bottom-up initiative introduced a new type of street, a model that made it possible to consider the street as a space for social interaction. Physical barriers and obstructions designed to reduce the speed of cars give users the impression that pedestrians can use street space with priority. In contrast, the volume of traffic is significantly reduced. The Woonerf invention still inspires new generations of Transport Engineers and urban planners to think of innovative technical solutions for street design beyond residential areas, which have given rise, for example, to strategies to control traffic speed (Traffic Calming) and also the “Shared Spaces” that complemented Woonerf’s concept (Dérive LAB, 2017).

2- Shared Spaces

Through Traffic Calming techniques, the design and vocation of a street can be transformed entirely. A great example of this is Shared Spaces. Although by way of differentiation, Woonerf refers to places where pedestrians have priority over cars, in shared spaces, the core principle is that all road users should be integrated, rather than separated from one another, with each having an equal right of way (Toth, 2009).

Regarding the evolution of the sharing concept, at the end of the 1970s, Woonerf was considered only a new category within the residential street typology. But villages in the north of the Netherlands continued to refine the strategy due to the high number of accidents involving children on the streets. In this context, Hans Moderman, an engineer originally from Leeuwarden city, in the northern Dutch province of Friesland, with the aim of finding cost-effective solutions to promote greater road safety, further developed the Woonerf idea. He proposed to remove all signage, traffic control elements, and gaps between different street surfaces with more complex contexts than residential types. The substantial change this time around was to remove all traditional signage in more complex street contexts beyond the settings of predominantly residential contexts. From this, road users really felt the need to be more attentive to the movement of others, to look at themselves, and inform where they were going to go. The result was a 40% decrease in car speed, thus reducing road incidents. It was not until the late 1990s that Moderman’s ideas gave rise to the term “Shared Space”. The impact of his proposals influenced a European Union project entitled “Shared Spaces”, in which spaces without signage, regulations, or specific modal segregation were proposed in the streets of cities in seven different European countries (Dérive LAB e SampaPé, 2017)

The concept of Shared Spaces emphasizes that communication between road users determines their behavior. At low speeds, people have more time for verbal and non-verbal communication and interaction. Besides, the low-speed limits and the sharing of spaces between modes make the street safer for bicycles and pedestrians without neglecting cars. This configuration is essential to ensure the permanence of individuals in the public space.

3- Play Streets

Street fairs and bazaars, markets, block parties, and other temporary events have breathed new life into our streets, indicating that they serve a complex social and economic purpose in addition to their utilitarian one. Our streets began to be modified in the early 1900s as a century of unrelenting motoring occupied and molded a large portion of the public space. (Lydon and Garcia, 2015).

With crowded conditions and a lack of urban park space, streets were the central play area for children and the primary social space for adults. Yet almost as soon as cars began dominating streets, citizens’ interventions were organized to take them back, even if only temporarily. One of these ideas was creating temporary play streets. A play street is a neighborhood block that residents apply to temporarily close to car traffic and transform into a place where kids are free to gather and play safely. Indeed, temporary repurposing of the street was revealed to be a very quick and low-cost way of maintaining community recreation areas and outdoor play spaces while also reclaiming neighborhood social life (Lydon and Garcia, 2015).

4- Open Streets

Newer in concept, Open Streets initiatives could be considered the evolution of the Play Streets movement (Lydon and Garcia, 2015). Both of them use a city´s primary form of open space, the public space of the street. In addition, Open Streets initiatives temporarily shut roadways to automotive traffic so that people may walk, jog, bike, dance, and participate in other physical and social activities instead of driving. These transformations allow cities to experience a range of actions that promote economic development, support schools, and provide new ways to enjoy cultural programming and life in the community (NACTO – National Association of City Transportation Officials, 2012).

The idea of Open Streets has spread to most major cities around the world, and people everywhere are gathering to enjoy car-free spaces. Few studies have actually quantified the benefits derived from Open Streets initiatives. But it remains that these benefits include, for both city and the citizens, environmental, economic, and social improvements (NACTO – National Association of City Transportation Officials, 2012). And, In the last 10 years (and especially during the pandemic period), Tactical Urbanism has become an excellent tool to promote actions like this in cities. As Tactical Urbanism works as a test for the space, it creates the possibility of stimulating the improvement of existing public policies or even the creation of new ones (Sansão-Fontes et al., 2020).

5- Pop-up initiatives in public spaces

This try-it-before-you-buy-it approach is known as a Pop-up. Translated for the cities, the Pop-up spaces create seasonal or one-day public spaces. A market, a plaza, a playground, a parklet, a temporary cycling path, or even a garden might be large or little. They establish public spaces where people may congregate, communicate, and remain.

Pop-ups have grown more popular in many cities, typically as a result of local individuals banding together to better their areas or change underutilized places. Although officially sanctioned, public pop-up spaces can also be found in cities worldwide (Scruggs, 2018). Actions like these, which are also examples of applications of the Tactical Urbanism tool, include the implementation of prototypes of temporary interventions in cities that can contribute to their replication in other places, making these urban planning actions in a network (Sansão-Fontes et al., 2020).

These are generally low-cost, high-impact projects that demonstrate how public spaces can be significantly improved to serve larger, people-oriented purposes, such as meeting and resting points, creating new green areas, becoming a small-scale urban redevelopment project, or even making a positive contribution to local businesses.

6- Pavement or sidewalk widening

Tactical urbanism projects are temporary and pop-up in nature. These strategies allow changes to streets or public spaces to “test” a prototype or solution before it is implemented on a more permanent basis. In that sense, pavement or sidewalk widening are another widespread application.

The design of sidewalk extensions reduces distances from pedestrian crossings and expands the space for passersby. The shorter the crossing distance for pedestrians, the lower the exposure to the risk of being run over. Sidewalk extensions narrow the road physically and visually and, at the same time, allow the creation of a space for permanence. It can provide areas for street furniture and banks, transport stops collective, trees, and landscaping. They must be implemented throughout the city, have different sizes, and combine rainwater and other public space improvements (NACTO – National Association of City Transportation Officials, 2018:88). This is a low-cost and rapid technique to apply Tactical Urbanism to redistribute space among users and better rebalance it through small-scale priority.

Now, if you are interested in started or participating in a Tactical Urbanism project that will designing cities for people, these are some recommendations suggested by “ The parCitypatory Blog ” that might be helpful (Puttkamer, 2020).

- “Start with a low-cost, low-time and DIY interventions and see how it goes, without losing sight of your long-term goal;

- Brainstorm with your team or neighbours on how to activate the space you are providing, for example through events, classes, food sales, chalkboards etc., in order to create a dialogue;

- Include social and traditional media by inviting them to report about your intervention;

- Try to engage the local government, private companies, local artists, business improvement districts and other important urban stakeholders.”

You can find the full list at: The parCitypatory Blog

References

metropolis – Revista Eletrônica de Estudos Urbanos e Regionais, 27, pp. 6–18.

Dérive LAB e SampaPé (2017) Ruas Compartilhadas. São Paulo. Available at: https://educacaoeterritorio.org.br/materiais/autor/derive-lab-e-sampape/ (Accessed: 12 April 2022).

Lydon, M. and Garcia, A. (2015) Tactical Urbanism: Short-term Action for Long-term Change. Washington, USA: Island Press.

NACTO – National Association of City Transportation Officials (2012) The open street guide. Available at: https://nacto.org/docs/usdg/smaller_open_streets_guide_final_print_alliance_biking_walking.pdf.

NACTO – National Association of City Transportation Officials (2018) Guia global de desenho de ruas. São Paulo: SENAC.

Puttkamer, L. (2020) Tactical Urbanism: Creating Long-Term Change in Cities Through Short-Term Interventions, parCitypatory Blog. Available at: https://parcitypatory.org/2020/07/31/tactical-urbanism/ (Accessed: 12 April 2022).

Sansão-Fontes, A. et al. (2020) Urbanismo Tático: um guia para as cidades brasileiras. Rio de Janeiro: Rio Books.

Scruggs, G. (2018) Can pop-ups pave the way to thriving public space in world’s cities?, Thomson Reuters Foundation. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-malaysia-cities-public-idUSKCN1GP1HW (Accessed: 12 April 2022).

Steinberg, L. (2015) Woonerf: Inclusive and Livable Dutch Street. Available at: https://www.humankind.city/post/woonerf-inclusive-and-livable-dutch-street (Accessed: 11 April 1022).

Toth, G. (2009) Where the Sidewalk Doesn’t End: What Shared Space has to Share, Project for publc spaces. Available at: https://www.pps.org/article/shared-space (Accessed: 11 April 2022).

Tiffany Nicoli is a researcher and holds a Master’s in Architecture and Urban Planning at the Federal University of Viçosa, Brazil. She is enthusiastic about active urban mobility and passionate about urban design. She feels that social exchanges inspire her to think about possible and more human cities. She enjoys walking and cycling and is always excited to study and discover new cities.

Related articles

Tactical Urbanism: Turning Streets into Social Spaces

Real-Time Traffic Management Solutions through Urban Data Platforms

Feminist Urbanism Approach to Urban Planning

5-Days UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

14th-18th July 2025

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “