Addressing the intense contradictory social concerns and their influence on the urban context has to be taken into serious consideration. Various outrages such as protests, demonstrations, and strikes are often being communicated in the form of violence. The urban theory has been a crucial part of social science research ever since the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century saw the rise of what are usually considered to be the first “modern” cities in Europe and North America. It seems that it is becoming more crucial that urban theory creates new ideas and thinking in connection to the construction of more inclusive and just urban futures as we progress into the second decade of what theorists, analysts, and critics refer to as “the urban age” or “the urban century.”

The theory is what makes it possible to think critically and grow intellectually. It is crucial for the creation of academic knowledge as well as for influencing the methodology that academics use to learn about cities.

Critical Urban Theory

The definition of Critical Urban Theory goes by “Critical urban theory rejects inherited disciplinary divisions of labor and statist, technocratic, market-driven and market-oriented forms of urban knowledge.” The importance and urgency of making our urban context more humanizing than its current form, it is important to be aware of the various concepts of Critical Urban Theory. The critical urban theory emphasizes how urban space is socially contested, ideologically influenced, and consequently flexible. The major components of urban theory constitute the assessment of socio-scientific ideologies, power, injustice, exploitation, and inequality prevailing in cities.

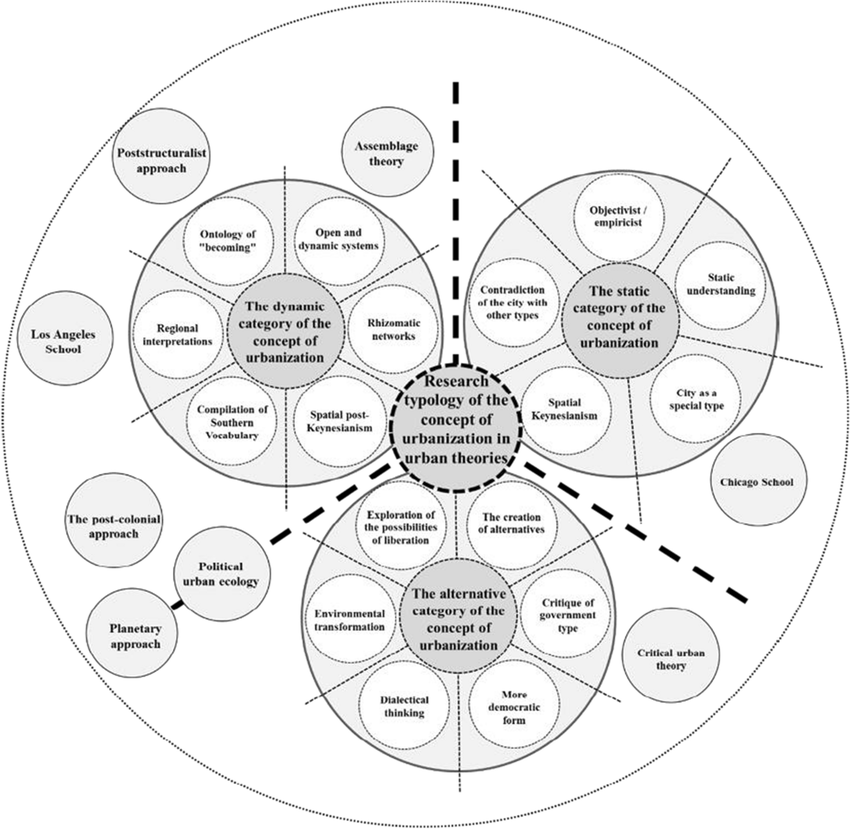

Ideas, vocabulary, and phrases used in urban theory are intended to understand cities and urban life. Urban theorists try to provide explanations for spatial expressions of cultural, economic, political, and social activities and processes. Urban theory can be expansive and include a high degree of abstraction, or it can be grounded on empirical, localized, or contextual knowledge of the processes that lead to the formation, operation, and change of cities. Both ‘big’ urban concerns and those centered on the ‘ordinary’ and daily can be discussed in urban theory. Urban theorists aim to make the city comprehensible or readable, but they are more concerned with explaining than with describing.

In addition to statist, technocratic, market-driven, and market-oriented forms of urban knowledge, critical urban theory critiques inherited disciplinary divisions of labor. Even while these possibilities are currently being stifled by prevailing institutional arrangements, practices, and ideologies, it asserts that a different, more democratic, socially equitable, and sustainable form of urbanization is still feasible. The historical specificity of any approach to critical social theory, whether urban or not, is one of the key issues to be highlighted below. The work of the Frankfurt School and Marx which was introduced during the initial stages of capitalism- Fordist-Keynesian and competitive are currently forward-moving destructive capitalism development.

The critical urban theory emphasizes how urban space is socially contested, ideologically influenced, and consequently flexible. Critique concepts, and more specifically critical theory, go beyond simple descriptors, though. They contain substantial social theory that comes from a variety of schools of enlightenment and post-enlightenment social philosophy. Thus, the critical urban theory is based on an antagonistic interaction with current urban forms in general as well as with inherited urban bits of knowledge. And it is therefore a constantly debatable field that uses, critiques, and sometimes even rejects prior theoretical work to provide fresh insights into the urban experience.

Main Components of Critical Theory

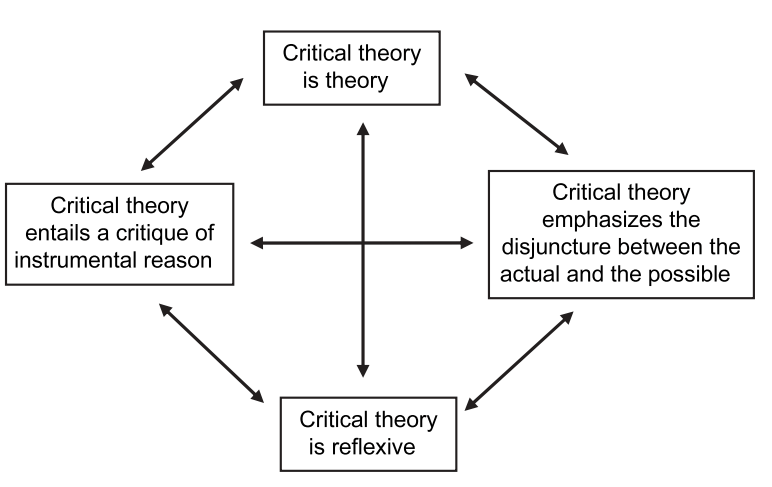

Critical theory can be categorized into 4 main propositions based on the theories of writers and researchers. They are: Critical theory is reflexive, Criticism of instrumental reason is a component of critical theory, Critical theory highlights the gap between the possible and the actual, and critical theory is theory. The above-mentioned propositions are mutually constitutive and closely intertwined.

Critical Theory is reflexive:

According to the Frankfurt School tradition, the theory is seen as simultaneously enabled and directed toward certain historical contexts and conditions. At least two important implications are derived from this view. First, the critical theory requires a complete rejection of any viewpoint that asserts to be ‘outside’ of the historically specific context, regardless of whether it is positivistic, metaphysical, transcendental, or any other. Second, critical theory from the Frankfurt School goes beyond a broad interpretive concern with the contextual nature of all knowledge. The question of how opposing, hostile forms of knowledge, subjectivity, and consciousness could evolve within a historical social formation is the subject of this essay more particularly.

Critical theorists approach this problem by highlighting the contradictory, shattered, or fragmented nature of capitalism as a social whole. There could be no critical consciousness of the totality if it were closed, non-contradictory, or complete. There would also be no need for critique, and criticism would be structurally impractical. As a result of society’s self-contradictory method of development, critique only becomes relevant since it conflicts with itself. Critical theorists, in this sense, are interested in more than just locating themselves and their research objectives within the development of modern capitalism.

Criticism of instrumental Reason is a Component of Critical Theory:

Using Max Weber’s works as a foundation, they argued against the societal spread of means-ends rationality that is directed toward the purposive-rational (Zweckrationale), an effective linking of means to objectives without questioning the ends themselves. Most importantly, in this case, Frankfurt School theorists also applied this critique to the field of social science. This critique had consequences for different areas of industrial organization, technology, and administration. In this view, the critical theory includes a strong rejection of instrumental modes of social scientific knowledge—that is, those created to enhance the efficacy and efficiency of current institutional structures, to control and dominate the social and physical environment, and therefore to support existing systems of power.

Frankfurt School researchers maintained that a critical theory must make clear its practical-political and moral tendencies, rather than embracing a limited or technical vision, in line with their historically reflective approach to social science. Instrumentalist approaches to knowledge inevitably assume their independence from the subject of study. Normative problems, however, cannot be avoided once that distinction is accepted and it is recognized that the knower is immersed inside the same real-world social context as the one being investigated. Thus, there is a direct link between the claim that reflexivity exists and the argument against instrumental reason.

Because of this, critical theorists do not refer to the issue of how to ‘apply’ theory to practice when they talk about the so-called theory/practice problem.

Critical Theory highlights the gap between the possible and the actual:

According to Therborn’s (2008) argument, the Frankfurt School accepts a dialectical critique of capitalist modernity—that is, one that both affirms and criticizes the systematic exclusions, oppressions, and injustices that are fostered by this social structure. Critical theory has to uncover the emancipatory potentials that are both ingrained in and simultaneously suppressed by modern capitalism, in addition to investigating the forms of power connected to it.

In a lot of Frankfurt School material, this tendency is characterized by a “search for a revolutionary subject,” or the desire to identify a catalyst for radical social change who could realize the potentials unleashed but repressed by capitalism. The Frankfurt School’s search for a revolutionary subject during the postwar period, however, resulted in a rather gloomy pessimism regarding the likelihood of social transformation and, particularly in the work of Adorno and Horkheimer, a retreat into relatively abstract philosophical and aesthetic concerns (Postone, 1993).

Marcuse takes a different stance on this issue in the “Introduction” to One-Dimensional Man, nevertheless. He concurs with his Frankfurt School peers that late 20th-century capitalism lacked any obvious “agents or agencies of social change” in contrast to the formative years of capitalist industrialization; in other words, the proletariat was no longer acting as a class “for itself.” In the context of this, Marcuse claims that the somewhat abstract nature of critical theory at the time he was writing it was inextricably related to the lack of a clear-cut agent of radical, emancipatory social transformation.

Critical Theory is Theory:

Critical theory is boldly abstract in the Frankfurt School. The evolution of formal concepts, generalizations about historical trends, deductive and inductive modes of argumentation, and many types of historical analysis are its distinguishing features. It is also defined by epistemological and philosophical reflections. It may also be based on empirical study, i.e., evidence, whether structured using conventional or critical methodologies.

As a result, critical theory is not meant to be a blueprint for any specific route of social change, a plan for achieving that change, or a how-to manual for social movements. It is specifically meant to educate the strategic viewpoint of progressive, radical, or revolutionary social and political actors, and it may well have mediations to the sphere of practice.

However, significantly, the Frankfurt School’s understanding of critical theory is concentrated on an analytically earlier moment of abstraction than the well-known Leninist question, “What is to be done?”

Correlation between Urbanization and Critical Urban Theory

Although Marx’s writings had a significant impact on the field of critical urban studies after 1968, the Frankfurt School’s writings have received little to no attention from those who have contributed to this discipline. The four statements that make up the conception of critical theory are as follows:

- They oppose the idea of theory as a “handmaiden” to immediate, practical, or instrumental concerns and emphasize the need for abstract, theological arguments explaining the nature of urban dynamics under capitalism.

- They reject market-driven, instrumentalist, and technocratic approaches to urban research that encourage the preservation and reproduction of already existing urban formations.

- They consider that knowledge of urban issues, especially critical viewpoints, is historically particular and mediated by power relations and

- They are interested in identifying opportunities for radical, alternative forms of urbanization that are latent but structurally suppressed in modern cities/

These ideas appear to together form an important epistemological foundation for the field as a whole, while any one contribution to critical urban theory may be more sensitive to some of them than to others. In this sense, Frankfurt School theorists as well as Marx and other thinkers had extensively tilled the intellectual and political ground before critical urban theory emerged. Since the creation of this subject in the early 1970s, methodological, epistemological, and substantive disagreements among critical urbanists have been quite prominent, sometimes even acrimonious.

However, given the early 21st century’s ongoing evolution and diversification of the field of critical urban studies, its status as a putatively “critical” theory merits close examination and organized discussion.

What is critical about critical urban theory, to borrow Fraser’s question from the topic of research covered in this issue of CITY? The meanings and modalities of critique can never be held constant; rather, they must constantly be reimagined concerning the unevenly evolving political-economic geographies of this process and the varied conflicts it engenders. This is because the process of capitalist urbanization continues to move forward in a manner that results in creative destruction on a global scale. Marx’s concept of critique and the Frankfurt School’s interpretation of critical theory was ingrained in historically particular forms of capitalism. Each of these approaches expressly considered itself to be immersed inside such a formation, consistent with their necessity for reflexivity and was geared self-consciously towards presenting the latter to critique.

Any attempt to adapt or recreate critical theory, whether urban or otherwise, in the early 21st century must place a prominent focus on this demand for reflexivity, as described above.

The Eight Thesis

A series of theses researched by various authors to address unique issues of critical urban theories are as follows.

Thesis 1: Space considered a politics

How is space politically charged? The leaders of the world in the age of cities, as well as their architects and urban planners, must have known that what Henri Lefebvre termed the “creation of space” had something to do with what Antonio Gramsci called political hegemony, both objectively and subjectively.

As readers of Mike Davis’s book on Los Angeles or Neil Smith’s book on the “revanchist city” can attest, Benjamin represents the primordial scene of capitalist-imperial-colonial urbanism, whose inherently violent form haunts the best exposés of radical urban thought even after modernity was discursively replaced by postmodernism and capitalism by globalization. But given the bleak situation, Davis describes in The Planet of Slums (2006), it’s easy to forget that architecture and urban planning once had a revolutionary goal: to fundamentally alter both space and society. Today, however, they are designed to mask social tensions rather than resolve them, if not doomed to pimping for city governments lusting for “public-private” affairs with corporate capital.

Thesis 2: Modernism as explained by Le Corbusier, Andre Breton, and Lenin

The unduly determined conjuncture framed by the two World Wars is the most misunderstood point in the sequence of historical events, especially in the age of postmodern amnesia: modernism.

Thesis 3: Modernization

What happened to the modernist revolution? By returning to Le Corbusier’s even more famous question, “Architecture or Revolution?” radical urban theory might do worse than confront this subject through architecture and urban planning. In the famous final sentence of Towards a New Architecture, which was published in 1923, he responded polemically to his rhetorical question: “Revolution can be avoided” (Corbusier 1986 [1923]: 289).

The message was that without a revolution, urban design and architecture could end Europe’s financial problems. It’s vital to keep in mind that this issue first came up during the height of modernism in Europe when both objective and subjective factors seemed to be favorable for a fundamental overhaul of both space and society in the Old World.

Thesis 4: Americanism

To put that into perspective, it is impossible to comprehend the transition of architecture, urban planning, and much else from modernism to modernization in the era of what Antonio Gramsci called “Americanism and Fordism” without considering the decline of the likelihood of revolution in the West.

Thesis 5: Postmodernism

The most insightful Marxist students of the city, Benjamin and Lefebvre, both regarded bourgeois urbanism in this way as a clash between the application of new technology and those utopian yearnings present in the social imaginary. The Dialectics of Seeing (1989: 89), written by Benjamin scholar Buck-Morss, calls capitalist “‘urban renewal’ projects'” a “classic example of reification” because they “attempted to create social utopia by changing the arrangement of buildings and streets – objects in space – while leaving social relationships intact.”

Thesis 6: Urban Theory of Marxist

The destiny of Marxism under similar conditions is mirrored by what happened to radical urbanism after the revolution was stymied by state socialism and removed from the political agenda in the West by military-Keynesianism. Both predicted a crippling separation between practice and theory, or a death of practice compensated by a new life in theory, which was itself mostly performed in the realm of academics rather than politics.

Thesis 7: City politics and economy

Architecture almost contains the necessary link with the economy, with which it interacts through commissions and land values, of all the arts. In other words, urbanization has a closer connection to the processes of capital than political conflict or cultural production, which, in the case of space, makes the dreaded economic decision to decide in the end more real than imagined. Space is made extremely adaptable to rigorous political-economic notions that are more economic than political by proximity to capital in this way. That level of accuracy in space economics comes at a cost, one that is unaffordable when it comes to space politics.

Thesis 8: Urban revolution is a Socialist revolution

A socialist revolution cannot occur without an urban revolution, and vice versa for an urban revolution to occur without a revolution in everyday life. In light of this, Lefebvre’s idea of the right to the city must be understood — not as yet another entry on the self-contradictory liberal democratic list of “human rights,” but rather as the right to a fundamentally different reality.

The "creative cities": New urban growth ideology

Urban philosophy is not always helpful in advancing “cities for people.” Some of these beliefs enhance the right to the city of those who currently live thereby serving as an ideological justification for cities built for “profit.” Despite its conceptual and methodological flaws, Richard Florida’s (2004, 2005) influential idea of the creative class has gotten positive feedback from local scientists and politicians in North America and Europe. Florida’s theory is regarded to contain highly specific theoretical claims, to provide appropriate empirical support for these claims, and to provide a workable plan for policy intervention.

Florida’s idea is seen as a “message of optimism” and as a direction for future prosperous economic development, particularly on the urban level. Florida has put forth a new urban growth theory that contends we can anticipate successful economic development in those cities or regions where the “creative class” members prefer to live and where they are concentrated; as a result, we should make cities and regions particularly appealing for this stratum of people. A good standard of living and recreational amenities should be provided for the creative class, according to Florida, which discusses the unique attraction elements of cities for members of the creative class.

The new urban growth ideologies present both philosophical and political concerns for critical urban theory. Among these urban booster ideas, the idea of creative cities has recently risen to the top. Urban policies that support the interests of the functional elites within neo-liberalizing capitalism are not justifiable.

The conceptual idea of a “creative class” uses the typically positive notion of “creativity” to conceal the dealer class’s harmful economic, political, and social behavior. For this reason, the idea supports those who already possess the right to the city.

References:

- Brenner, N. (2012). Cities for People, Not for Profit Critical Urban Theory and the Right to the City. Routledge.

- Brenner, N. (2017). Critique of urbanization : selected essays. Bauverlag ; Birkhäuser.

- Jayne, M., & Ward, K. (2017). Urban theory : new critical perspectives. Routledge.

- Litman, T. (2022). Urban sanity. Victoria Transport Policy.

Amodini Allu

About the Author

As an amateur enthusiast, who is an Architect by day and an observer as a whole pushes her limits to explore herself as an artist and relate her works with Architecture. She truly believes that studying Architecture has laid her a basic platform to try every possible thing to exhibit her works. Over the years she developed the habit of documenting things visually and trying them pen down as trying to decipher the spatial meaning. She also discovered a love for writing through her works while working as an Editorial intern for an Architectural platform. Which led her to begin a blog of her observations about usual things happening around her through the eyes of an Architect.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

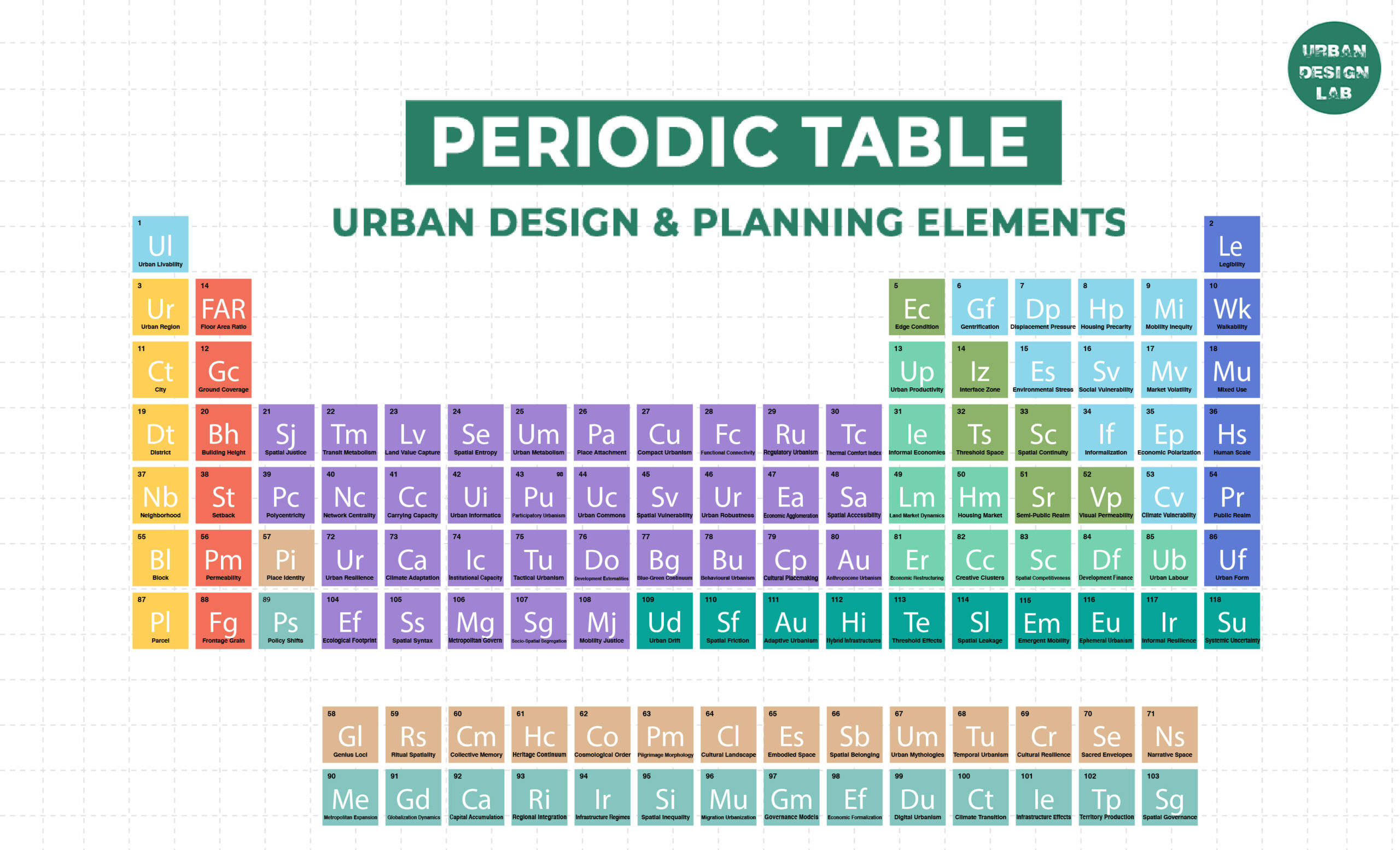

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

Best Landscape Architecture Firms in Canada

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “

One Comment

Hello, I used the valuable content of your article, thank you.