Cultural Landscapes: Exploring their Social Dimension

Understanding Culture and Cultural Landscapes

Cultural Landscapes are the convergence between the nature and culture and are characterized by the conservation and protection of ecological processes, natural resources, landscapes and cultural biodiversity (Schmitz & Jáuregui, 2021). They are the landscapes that have influenced, affected or shaped by the involvement of human interactions with nature. Cultural Landscapes are generally recognized as works of art, narratives of culture, and expressions of regional identity (About Cultural Landscapes, 2022). Cultural landscapes and their setting plays an important role in people’s quality of life and sense of belonging, all these factors contributing to the overall development of landscape perception and character (Milan, 2017).

Defining Cultural Landscape

Different governing agencies around the world have defined these types of landscapes as:

• The National Park Service – ‘a geographic area, including both cultural and natural resources and the wildlife or domestic animals therein, associated with a historic event, activity, or person, or exhibiting other cultural or aesthetic values.’

• UNESCO – ‘Combined works of nature and of man” that illustrate the evolution of human society and settlement over time, under the influence of physical constraints and/or opportunities presented by their natural environment, and of successive social, economic, and cultural forces, both external and internal.’

• The Landscape Cultural Foundation – ‘Cultural landscapes provide a sense of place and identity; they map our relationship with the land over time; and they are part of our national heritage and each of our lives.’ (Understand Cultural Landscapes, 2022)

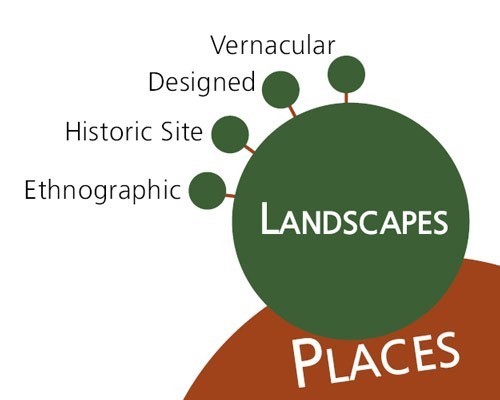

Types of Cultural Landscapes

Generally there are four types of cultural landscapes, namely:

1. Historic Designed Landscape – A landscape designed or laid by a landscape architect, master gardener, horticulturist or architect according to design principles. These types of landscapes are generally associated with any significant event, person or trend in landscape architecture or gardening, or an important development in the theory and practice of landscape architecture. Examples include public parks and campus; royal estates.

2. Historic Vernacular Landscape – A landscape that is governed and evolved through the use, construction or physical layout by the people whose activities or occupancy shaped it. This type of landscape reflects the physical, biological, and cultural character of those everyday lives. Examples includes rural villages; agricultural villages (Understand Cultural Landscapes, 2022).

3. Historic Site – A landscape significant for its association with a historic event, activity, or person. Examples include battlefields; president’s, kings or queens house properties.

4. Ethnographic Landscape – This type of landscape comprises of both natural and cultural resources that are associated with people and are collectively known as heritage resources. Examples include contemporary settlements; religious or sacred sites and monuments; geological structures (Cultural Landscapes).

ter gardener, horticulturist or architect according to design principles. These types of landscapes are generally associated with any significant event, person or trend in landscape architecture or gardening, or an important development in the theory and practice of landscape architecture. Examples include public parks and campus; royal estates.

Characteristics of Cultural Landscapes

Both tangible and intangible characteristics are associated with cultural landscapes. They are:

- Natural Systems and Features

- Spatial organization

- Land use

- Cultural traditions

- Cluster arrangement

- Circulation

- Topography

- Vegetation

- Buildings and structures

- Views and vistas

- Constructed water features

- Small-scale features

- Archaeological sites

Cultural Landscapes around the World: Case Examples

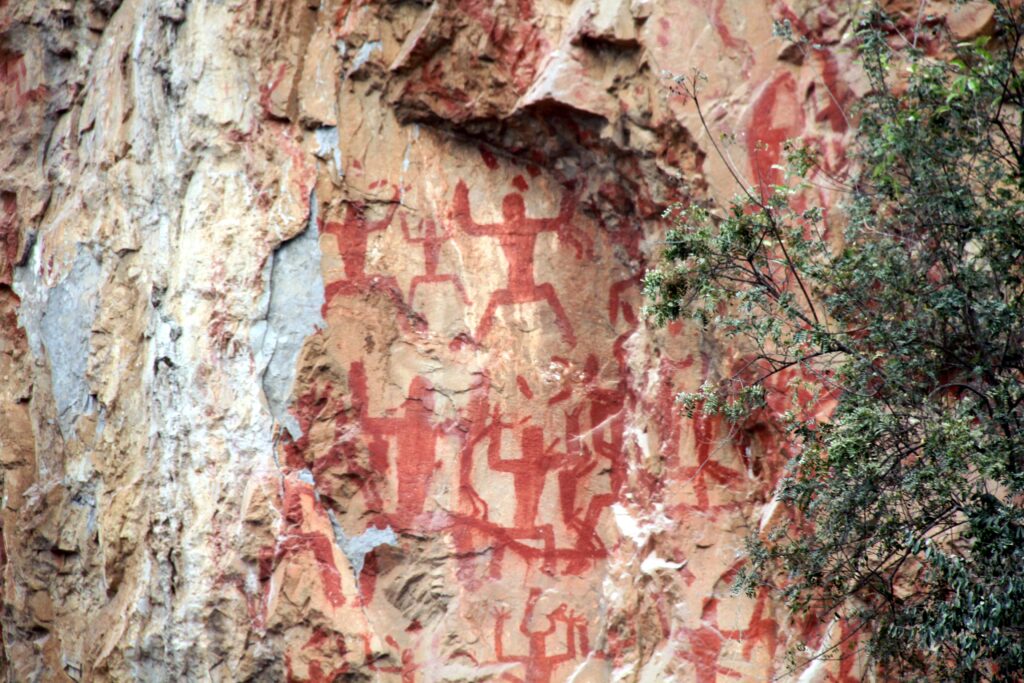

1. Cultural Landscape of China: Zuojiang Huashan Rock Art

Located on the steep cliffs in the border regions of southwest China, there is an extensive assembly of historical rock art that were painted on limestone cliff faces comprising of total of 38 sites that the life and rituals of the Luoyue people. The paintings are basically red in colour and were executed by using a mixture of red ochre (hematite), animal glue and blood. In a surrounding landscape of karst, rivers and plateaux, these paintings depict human figures as well as animals along with bronze drums, knives, swords, bells, and ships (Zuojiang Huashan Rock Art Cultural Landscape).

The rock paintings not only show us the artistic achievements of the ancient Luoyue people, but also the richness of their social life millennia ago, and their diligence, courage and tenacity. The spectacular views of the cliff murals, the mystical cultural background of ancient Luoyue people, and the important archaeological value with unsolved puzzles attract a vast community of visitors, experts and scholars to experience the magnificent view of Zuojiang Huashan Rock Art Landscape. (Zuojiang Huashan Rock Art Cultural Landscape – UNESCO World Heritage).

2. Cultural Landscape of Bali Province – The Subak System: Rice Terraces and their Water Temples

The cultural landscape of Bali consists of five rice terraces and their water temples that cover 19,500 ha. The temples are the focus of a cooperative water management system of canals and weirs, commonly known as subak, which dates back to as early as the 9th century (Cultural Landscape of Bali Province: the Subak System as a Manifestation of the Tri Hita Karana Philosophy).

The areas included within these landscapes are:

- Supreme Water Temple of Pura Ulun Danu Batur

- Lake Batur

- Subak Landscape of the Pakersian Watershed

- Subak Landscape of the Catur Angga Watershed

- The Royal Water temple of Pura Taman Ayun (Bali Subak system)

This landscape embodies the Balinese philosophical principle Tri Hita Karana (three causes of goodness) that aims to create harmony between humans and the spiritual realm, between humans and nature, and among humans. The Subaks ensure the equitable distribution of water to farms, maintain the irrigation system, mobilize resources and mutual assistance, resolve conflicts, and ensure the performance of rituals (Salamanca, Nugroho, Osbeck, Bharwani, & Dwisasanti, 2015).

The components of these Subak Landscapes are:

- Forests that protect the water supply

- Terraced paddy landscape

- Rice fields connected by a system of canals, tunnels and weirs, villages, and temples of varying size and importance (Cultural Landscape of Bali Province: the Subak System as a Manifestation of the Tri Hita Karana Philosophy)

The subak generally controls the construction and maintenance of the channelling system and management of the water flow in order to ensure the fair distribution of this precious resource. Since farmers depend on the successful irrigation of the fields, the different subaks form a close bond that unites into a single system that has been handed down the generations for over a thousand years (Subak – The Cultural Landscape of Bali, 2018).

3. Cultural Landscape of Australia: Uluru-Kata Tjuta

Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park is a protected area in the Northern Territory of Australia. The landscape is governed by two spectacular geological formations:

- Uluru, an immense rock formation comprising of red sandstone in the form of a dome, and

- Kata Tjuta, the rock domes located west of Uluru, form a fundamental part of the traditional belief system of one of the oldest human societies in the world. The enormous rock formations dominate the surrounding vast red sandy plain of central Australia, which provides habitat for an incredible variety of rare or threatened plants and animals. The traditional owners of Uluru-Kata Tjuta are known as Anangu (Uluru Kata Tjuta National Park).

The park has been home to Anangu people for more ten thousand years and contains significant physical evidence of one of the oldest continuous cultures in the world. Anangu is the term that Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara Aboriginal people, from the Western Desert region of Australia and Anangu law, the Tjukurpa, is the foundation of the Anangu living cultural landscape associated with Uluru Kata Tjuta National Park. The Tjukurpa is an outstanding example of traditional law and spirituality and reflects the relationships between people, plants, animals and the physical features of the land. Tjukurpa was founded at a time when ancestral beings, combining the attributes of humans and animals, camped and travelled across the landscape. They shaped and created all of the features of the land and its landscapes. The actions of these ancestral beings also established a code of behaviour that continues to be followed by Anangu today. The landscape is imbued with creative powers of cultural history through Tjukurpa and related sacred sites. Powerful religious, artistic and cultural qualities are associated with the cultural landscape created by Mala, Lungkata, Itjaritjari, Liru and Kuniya ancestral beings. Within this landscape there is a gender-based cultural knowledge and responsibilities system, where Anangu men are responsible for looking after sites and knowledge associated with men’s law and culture, and equally Anangu women are responsible for looking after sites and knowledge associated with women’s law and culture (Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park). The park flora represents a large portion of plants found in Central Australia and many of these species are considered as rare and endemic and they are divided into four main categories:

- Punu – trees

- Puti – shrubs

- Tjulpun-tjulpunpa– flowers

- Ukiri – grasses

4. Cultural Landscape of India: Ghats of Varanasi

The cultural landscapes of India are often term as intellectual landscapes as they are formed through the meanings of religious, cultural and aspects credited to the geographical components with active interaction with the communities over the generations. The geographical condition of India comprises of setting of hills, rivers and forests which has given rise to many different forms of cultural beliefs among the communities which is reflected in their landscapes. (Thakur, 2011)

The rivers present in India are of great cultural and religious essence as they are related to different mythological beliefs by different communities. One such rive is the Rive Ganga which is considered as an embodiment of Goddess Shakti and is of great cultural and natural importance. Most of the famous cultural cities and towns are situated on the banks of river Ganga stretching from Uttarakhand to West Bengal. These cities are considered as centres for spiritual attainment and have thus formed a landscape of their own (Sati, 2021). One of the prominent examples of these types of cities is the City of Varanasi. The types of cultural landscapes predominant along the stretch are the —ghats (steps and landings) lined by temples and other public buildings, pavilions, kunds (tanks), streets and plazas. The ghats act as minute spaces of public spaces along the dense city and the river Ganga. The Ghats are aligned with different shapes like square, rectangle, octagonal and circular platforms divided into smaller bays to protect them from erosion. Over the course of time the Ghats have become the iconic image of Varanasi and generate a strong mental image in the mind of the observer. Festivals are celebrated along the Ghats precinct all throughout the year and are tied to different seasons (Singha, 2018).

5. Cultural Landscape of Majuli: Satras and their influence on the landforms

Majuli is one of the largest inhabited mid river deltaic islands and is located in the upper reaches of the river Brahmaputra and is considered as a unique spiritual Indian cultural landscape. The island of Majuli was created as a result of periodical natural changes in the course of the river Brahmaputra caused by frequent major earthquakes in different times as well as high floods (Majuli: Introduction). Throughout the frame of history the Brahmaputra River valley along with its tributaries was ruled by kingdoms of diverse ethnic groups settling along the plains, hills and river-side and was constant in conflict with each other (Thakur, 2011).

With the introduction of Vaishnavism in the 15th – 16th Century and the monastic foundations of Satras by Saint Shri Shri Sankaradeva, redefined the Assamese socio-cultural dimension. These Satras, which had an immense area of influence, merged the diverse ethnic groups into a democratic casteless society in their unique ecological context. Each Satras had set up their own tradition and practices and governed a spiritual control over the members through social orders and evolved into a context- specific management system that bridged socio-religious practices within its natural setting. Diverse ethnic groups performed distinct activities (traditional occupation) that enabled management of natural resources and withstood natural calamities. Traditionally, respective Satras developed a series of synchronized systems of resource management that closely followed the natural geo- hydrological dynamics of the island and specifically responded to the area of their influence. Each community thereon, were entrusted unique and significant duties within the overall framework that formed an integral part of the spiritual and cultural fabric of the Assamese society which still continues till date (Thakur, 2011).

The current scenario of Cultural Landscape due to increase rate of Urban Development

The current progress of global change such as agricultural intensification, rural abandonment, urban sprawl, increased in population, increased housing demands, climate change and socioeconomic dynamics, are threatening cultural landscapes worldwide. Even though this loss is often unstoppable because of rapid and irreversible social–ecological changes, rational protection measurement by the authorities can preserve cultural landscapes while promoting the sustainability of social–ecological systems. The challenges faced by the areas particularly in case of urban regions are very steep in regards for conservation of cultural landscapes. Challenges like inadequacy of urban conservation management policies and processes focused on heritage, absence of skills, training, and resources amongst decision makers and persistent conflict and competition between heritage conservation are some of the factors that need to be governing while safeguarding the cultural landscape of a region (Schmitz & Jáuregui, 2021).

Cultural Landscape and their Preservation – Global Policies and Initiatives

The organisation overlooking their preservation and conservation from the global threats and Anthropocene activities are as follows:

- Cultural landscapes and their links to the conservation of biological diversity are now recognized under the 1972 UNESCO Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (Preserving cultural landscapes).

- TheInternational Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) works for the conservation and protection of cultural heritage places. The International Scientific Committee for Cultural Landscapes (IFCCL) was created by ICOMOS in partnership with the International Federation of Landscape Architects (IFLA) in 1970 and has ever since successfully contributed to ICOMOS.

- The Cultural Landscape Foundation (CLF) provides people with the ability to see, understand and value landscape architecture and its practitioners, in the way many have learned to do with buildings and their designers.

- Created in 1916, the National Park Serviceis the U.S. Federal Agency that manages all National parks, many National monuments, and other conservation and historical properties with various title designations.

- American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) founded in 1899, deals with the ideas to lead, to educate, and to participate in the careful stewardship, wise planning, and artful design of cultural and natural environments (World Rural Landscape).

- The International Union for Conservation of Nature(IUCN) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natural resources. It is involved in data gathering and analysis, research, field projects, advocacy, and education. IUCN’s mission is to “influence, encourage and assist societies throughout the world to conserve nature and to ensure that any use of natural resources is equitable and ecologically sustainable”.

- The Council of Europe Landscape Conventionpromotes the protection, management and planning of the landscapes and organises international co-operation on landscape issues. The Convention sets great store by identifying and assessing landscapes through field research by professionals working in conjunction with local inhabitants. Each landscape forms a blend of components and structures: types of territories, social perceptions and ever-changing natural, social and economic forces (The European Landscape Convention (Florence, 2000)).

Criteria for Selection of Cultural Landscape by World Heritage Lists

To be included on the World Heritage List, sites must be of outstanding universal value and meet at least one out of ten selection criteria.

- To represent a masterpiece of human creative genius

- to exhibit an important interchange of human values, over a span of time or within a cultural area of the world, on developments in architecture or technology, monumental arts, town-planning or landscape design;

- to bear a unique or at least exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition or to a civilization which is living or which has disappeared;

- to be an outstanding example of a type of building, architectural or technological ensemble or landscape which illustrates significant stages in human history;

- to be an outstanding example of a traditional human settlement, land-use, or sea-use which is representative of a culture (or cultures), or human interaction with the environment especially when it has become vulnerable under the impact of irreversible change;

- to be directly or tangibly associated with events or living traditions, with ideas, or with beliefs, with artistic and literary works of outstanding universal significance.

- to contain superlative natural phenomena or areas of exceptional natural beauty and aesthetic importance;

- to be outstanding examples representing major stages of earth’s history, including the record of life, significant on-going geological processes in the development of landforms, or significant geomorphic or physiographic features;

- to be outstanding examples representing significant on-going ecological and biological processes in the evolution and development of terrestrial, fresh water, coastal and marine ecosystems and communities of plants and animals;

- to contain the most important and significant natural habitats for in-situ conservation of biological diversity, including those containing threatened species of outstanding universal value from the point of view of science or conservation (The Criteria for Selection).

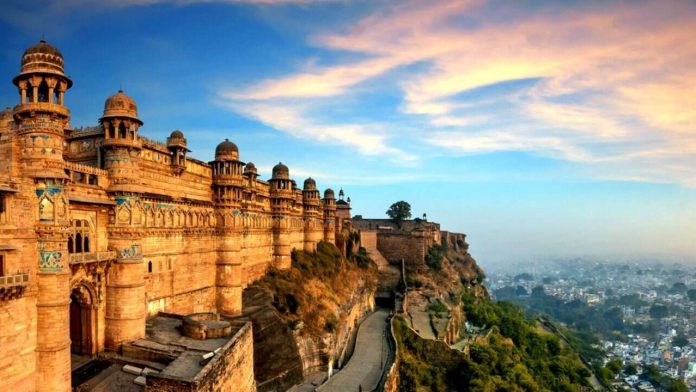

The Historic Ensemble of Orchha – Nominated Cultural Landscape of India

Orchha is a historical town in the Niwari district of Madhya Pradesh, India with a total population of around 12,000 inhabitants. The town encompasses a very dense collection of the historical buildings, gardens and traditional housings. It was the seat of an eponymous former princely state of central India, in the Bundelkhand region. Even though the seat of power changed frequently in Orchha, the city flourished and grew under the leadership of Bundeli kings and became the inception point for a new style of architecture known as the Bundeli architectural style.

As the capital of the Bundela dynasty from 1531-1783 CE, Orchha’s monuments, gardens, temples, and murals as an ensemble, represent remarkable evolution in town planning, fortification of settlement, in buildings, garden design and art. The cultural landscape fostered various traditions of myths, ballads, literary and folk arts. The fortification, town planning, the garden design in Orchha evolved into a unique new form with amalgamation of Mughal style of gardens, Rajput Fort gardens, Hindu sacred groves and evolved hydrology systems. These gardens were strategically located around area of dense activities to provide relief to the urban fabric and to enhance the views from the high stories of palaces and temples. Thus, Orchha houses a unique ensemble of monuments and sites to understand the organization of the 16th-18th century society in India.

Orchha is a living cultural site where the new development has not been too much against the character of the historical township. The cultural landscape survives as a discernible palimpsest, its historic layers still overpowering the new development. Orchha has retained the geomorphological character with evident historical connections between the settlement, the river Betwa and the forest around it (The Historic Ensemble of Orchha).

Need for Conservation of Cultural Landscapes

As an integral form of world heritage, cultural landscapes have evolved linked with production systems and living space and have become an important topic of rural studies worldwide. With the influence of globalization and the notion of sustainable development, cultural landscapes have received and gathered attention globally. Cultural landscapes should not only be preserved but also recognised as a component of heritage that needs to gain communities attention. As a part of heritage, these cultural landscapes adapts to various needs and purposes, such as research, assessment and the recording and awakening of traditions, and can help individuals, groups, nations, and transnational communities develop and strengthen social identity, raise awareness, and enrich tourism content. Cultural landscapes can coexist with communities through their associative values such as:

- Sustainability of production by working with the community.

- By maintain the traditional activities of an area and giving them the outstanding universal value.

- Involving local inhabitants to safeguard the resources who are generally considered as the guardians of the local cultural values.(Shen & Chou , 2021).

The inclusive development of urban heritage has the possibility to encourage a shared cultural identity of both tangible (materials) and intangible (psychological remnants) of a nation’s past and combining the essence of unity through people, places and culture (Udeaja , et al., 2020).

Reference

About Cultural Landscapes. (2022). Retrieved from The Cultural Landscape Foundation – connecting people to places: https://www.tclf.org/places/about-cultural-landscapes

Bali Subak system. (n.d.). Retrieved from World Heritage Site for World Heritage Travellers: https://www.worldheritagesite.org/list/Bali+Subak+system

Cultural Landscape of Bali Province: the Subak System as a Manifestation of the Tri Hita Karana Philosophy. (n.d.). Retrieved from UNESCO World Heritage Conservation: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1194/#:~:text=The%20cultural%20landscape%20of%20Bali,back%20to%20the%209th%20century.

Cultural Landscape of the Sondondo Valley. (n.d.). Retrieved from World Heirtage Site for World Heritage Travellers : https://www.worldheritagesite.org/tentative/id/6417

Cultural Landscape of the Sondondo Valley. (n.d.). Retrieved from UNESCO World Heritage Site: https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/6417/

Cultural Landscapes. (n.d.). Retrieved from Nature and Society: https://www.landscapepartnership.org/maps-data/nature-and-society/cultural-historic/cultural-landscapes-1

Majuli: Introduction. (n.d.). Retrieved from Majuli Cultural Landscape Management Authority: Promoting and preserving the rich heritage of Majuli: http://majulilandscape.gov.in/

Milan, B. S. (2017, 06). Cultural Landscapes: The Future in the Process. Journal of Heritage Management, 2(1).

Preserving cultural landscapes. (n.d.). Retrieved from The Encyclopedia of Worl Problems and Human Potential: http://encyclopedia.uia.org/en/strategy/213376

Salamanca, A. M., Nugroho, A., Osbeck, M., Bharwani, S., & Dwisasanti, N. (2015). Managing a living cultural landscape: Bali’s subaks and the UNESCO World Heritage Site. Stockholm Environment Institute. Bangkok: Stockholm Environment Institute.

Sati, V. P. (2021). The Ganges: Cultural, Economic and Environmental Significance. Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

Schmitz, M. F., & Jáuregui, C. H. (2021, 03). Cultural Landscape Preservation and Social–Ecological Sustainability. Sustainability.

Shen, J., & Chou , R. J. (2021, 04). Cultural Landscape Development Integrated with Rural Revitalization: A Case Study of Songkou Ancient Town. Land, 10(4).

Singha, D. (2018, 09). Ganga nadi – Ghats of Varanasi on the Ganga in India : The cultural landscape reclaimed.

Subak – The Cultural Landscape of Bali. (2018, 05). Retrieved from International Bali Resort: https://www.bali.intercontinental.com/subak-the-cultural-landscape-of-bali

Thakur, N. (2011). Indian Cultural Landscapes: Religious pluralism, tolerance and ground reality. Journal of SPA: New Dimensions in Research of Environments for Living “The Sacred”, 3.

The Criteria for Selection. (n.d.). Retrieved from UNESCO World Heritage Convention: https://whc.unesco.org/en/criteria/#:~:text=To%20be%20included%20on%20the,out%20of%20ten%20selection%20criteria.

The European Landscape Convention (Florence, 2000). (n.d.). Retrieved from Council of Europe: https://www.coe.int/en/web/landscape/the-european-landscape-convention

The Historic Ensemble of Orchha. (n.d.). Retrieved from UNESCO World Heritage Convention: https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/6404/

Udeaja , C., Trillo, C., Awuah, K., Makore, B., Patel, D., Mansuri, L., et al. (2020, 03). Urban Heritage Conservation and Rapid Urbanization: Insights from Surat, India. Sustainability, 12(6).

Uluru Kata Tjuta National Park. (n.d.). Retrieved from Australia’s World Heritage: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/env/pages/d285fa76-222b-4531-8914-964c55851332/files/uluru-factsheet.pdf

Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. (n.d.). Retrieved from UNESCO World Heritage Convention: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/447/

Understand Cultural Landscapes. (2022, 10). Retrieved from National Park Service: https://www.nps.gov/subjects/culturallandscapes/understand-cl.htm

World Rural Landscape. (n.d.). Retrieved from World Rural Landscape: http://www.worldrurallandscapes.org/home/links-and-sources/institutions/#:~:text=UNESCO%20has%20195%20Members%20and%20eight%20Associate%20Members.&text=The%20International%20Council%20on%20Monuments,protection%20of%20cultural%20heritage%20places.

Zuojiang Huashan Rock Art Cultural Landscape. (n.d.). Retrieved from UNESCO World Heritage Convention: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1508/

Zuojiang Huashan Rock Art Cultural Landscape – UNESCO World Heritage. (n.d.). Retrieved from China Discovery: https://www.chinadiscovery.com/guangxi/zuojiang-huashan-rock-art-cultural-landscape.html

Ankur Jyoti Dutta is a landscape architect and academic who completed his master’s degree in landscape architecture from the School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi in 2021. He has 3.5 years of experience in both industrial and academic fields, focusing on concepts of nature and culture in the Anthropocene, Cultural Landscapes and their social dimensions, Urban Ecology, Urban Regeneration, Landscape Urbanism, Ecological Urbanism, idea of Sustainability and Energy Efficient Landscapes. He has published articles on Efficient Landscape Design Practices for Universities, Wetlands for Ecological Development in Current Urban Areas, and Threats to Urban Landscape Resources. He currently works as an Assistant Professor (Contract) at the Department of Landscape Architecture at the School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “