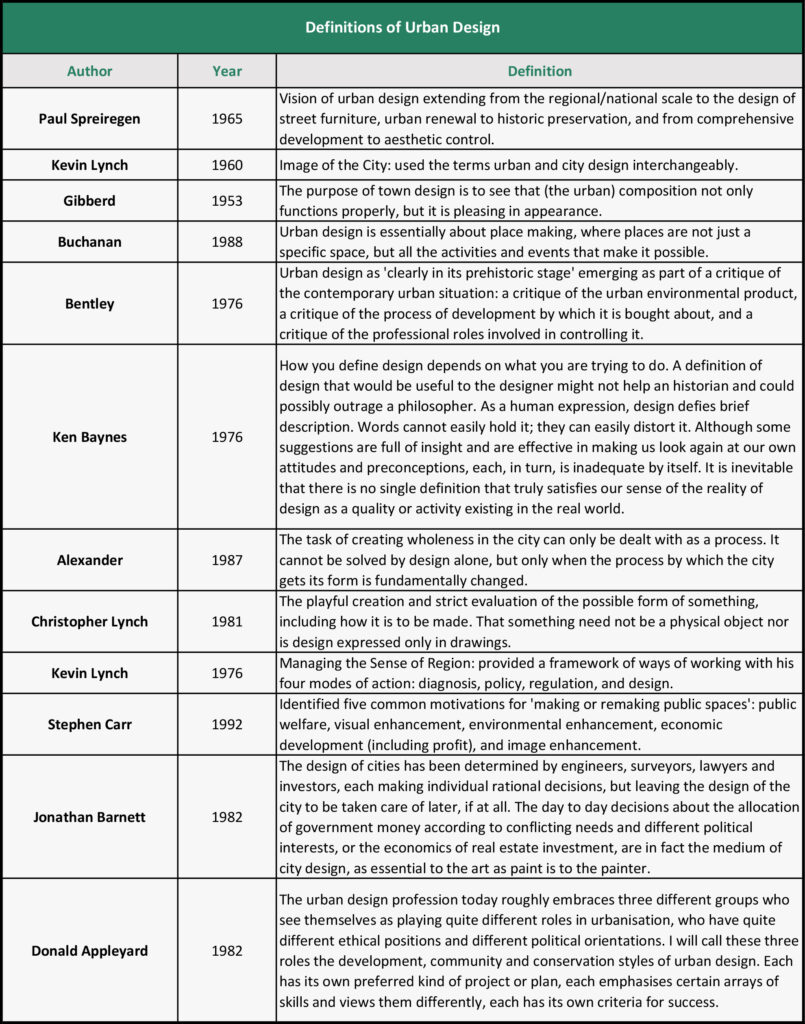

Definitions of Urban Design

Introduction

Urban design is a multifaceted and intricate concept that has been interpreted and defined in myriad ways by different scholars, practitioners, and theorists over the years. It is a field that defies simple categorization, encompassing a wide range of disciplines, perspectives, and concerns. The complexities inherent in the very terms “urban” and “design” contribute to the challenges in arriving at a singular, universally accepted definition. The term “urban” itself is subject to varying interpretations, with some urban designers extending their purview beyond strictly urban contexts to include rural settings and environments. Similarly, the notion of “design” is laden with nuances and complexities, as it encompasses not only the physical shaping of spaces but also the processes, motivations, and experiences that give those spaces meaning and purpose.

The article presents a comprehensive array of definitions and viewpoints on urban design, reflecting the diverse nature and multidimensional concerns of this field. These varying perspectives highlight the richness and depth of thought that has been dedicated to understanding and articulating the essence of urban design. From architectural and aesthetic considerations to social, economic, and environmental factors, the definitions captured in the document span a broad spectrum, underscoring the interdisciplinary nature of urban design and its role in shaping the built environment at multiple scales and levels of engagement.

This diversity of viewpoints is not merely a reflection of academic discourse but is grounded in the practical realities and challenges faced by urban designers in their daily work. The article reveals how the motivations, priorities, and contexts of different stakeholders – ranging from developers and policymakers to community advocates and conservationists – shape their understanding and approach to urban design. As such, the definitions presented offer insights into the complex interplay of forces that shape the urban realm, highlighting the need for urban design to navigate and reconcile potentially competing interests and objectives.

The Origins and Evolution of Urban Design

The term “urban design“ emerged in North America during the late 1950s. In 1957, the American Institute of Architecture established a Committee on Urban Design, and the first university course on the subject was introduced at Harvard in 1960. The Committee commissioned Paul Spreiregen to write a series of articles on urban design for the AIA Journal, which later formed the basis of his book “Urban Design: The Architecture of Towns and Cities,” published in 1965. Spreiregen envisioned urban design as a comprehensive field, spanning regional and national scales down to the design of street furniture. His approach included urban renewal, historic preservation, comprehensive development, and aesthetic control.

While Spreiregen’s vision was ambitious, other writers like Kevin Lynch and Jane Jacobs provided more critical and impactful insights that shaped the field’s evolution. Lynch, in his seminal work “The Image of the City” (1960), used the terms “urban design” and “city design” interchangeably. However, Jacobs warned against viewing cities and neighborhoods purely as architectural problems, emphasizing that such an approach replaces the essence of life with artifice.

The concept of urban design soon crossed the Atlantic and integrated with existing British traditions of townscape and town design, championed by figures like Cullen, Gibberd, Holford, and Sharpe. However, the late 1960s and early 1970s were challenging times for environmental professions, including urban design. Public dissatisfaction with the environments produced by these professions led to criticism. Edgar Rose, in particular, criticized the legacy of urban design for relying on outdated architectural rules and failing to recognize the complexity of the design process.

Despite the difficulties of the 1970s, this period was rich in design thinking and theorizing. Many foundational ideas of modern urban design emerged during this time, influenced by thinkers such as Alexander, Barnett, Canter, the Kriers, Norberg-Schulz, Relph, Venturi, and the consistently insightful Kevin Lynch. By 1980, Bentley optimistically described urban design as emerging from a critique of contemporary urban situations.

Today, the term “urban design” encompasses a wide range of activities and scales, from the design of individual building facades or modest environmental improvements to the creation of entire new settlements. It also includes aesthetic control or design review by public authorities. While there is general agreement that urban design exists as a discipline, there is less consensus on its exact scope. This ambiguity stems from the diverse range of work undertaken and the varying perspectives on the designer’s role in development and urban design processes

The Origins and Evolution of Urban Design

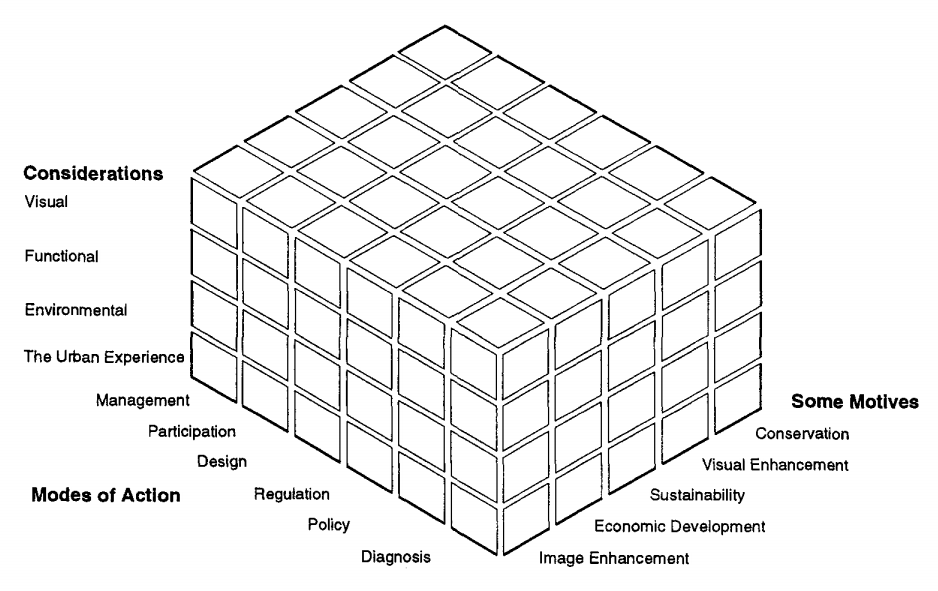

Urban design is a multifaceted field that encompasses various considerations, motives, and modes of action. The nature of urban design practice is shaped by the diverse perspectives and experiences of practitioners, researchers, and educators in the field. Some key considerations in urban design include visual aspects, functional elements, environmental factors, and the overall urban experience. Additionally, urban design is driven by motives such as public participation, conservation, sustainability, economic development, and image enhancement.

There is no simple way to describe the practice of urban design, as it can only be fully understood through hands-on experience. Traditionally, urban designers have played two primary roles: as architect/urban designers directly involved in the creative commissioning and design of development projects, or as planner/urban designers guiding and controlling the activities of others to protect the public interest from an urban design standpoint.

However, urban design should not be defined exclusively by these two roles, nor should these roles be simplistically equated with public versus private sector employment. Instead, it is essential to recognize the existence of different kinds of urban design practices, each with its own unique perspectives, ethical positions, and political orientations.

Donald Appleyard identified three distinct styles of urban design practice: development, conservation, and community-based urban design. The development style focuses on economic growth, catering to developers’ interests and promoting profit-driven projects aimed at attracting investment and spurring economic development. In contrast, the conservation style, also known as environmental quality design, primarily responds to the negative consequences of urban change, often operating outside the development process to prioritize the preservation of existing environments.

The community urban design style emerged in residential neighborhoods, emphasizing public participation as a crucial technique. Projects in this style are typically modest in scope and locally focused, with community development as a prime motive. This style aligns with approaches like the West Silvertown Planning Weekend organized by Hunt Thompson Associates for the Urban Villages Forum, which combined a participatory process with a relatively grand vision.

While the concept of “designing cities without designing buildings” proposed by Jonathan Barnett could potentially encompass aspects of all three styles, in practice, the idea of different urban design styles provides a more accurate representation of the diverse nature and concerns within the field. As our understanding of urban design evolves, the possibility of new styles emerging remains open.

Definitions of Urban Design

Christopher Jones (1980), in his seminal work on design methods, offered a succinct yet thought-provoking definition, describing designing as “to initiate change in man-made things.” This broad characterization encompasses the fundamental essence of urban design as a catalyst for transforming the built environment.

Ken Baynes (1976), in his insightful exploration of design, acknowledged the inherent complexity and subjectivity involved in defining the term. He astutely observed that “How you define design depends on what you are trying to do. A definition of design that would be useful to the designer might not help an historian and could possibly outrage a philosopher.” This recognition of the multifaceted nature of design highlights the diverse perspectives and priorities that shape its interpretation.

Paul Spreiregen (1965) envisioned urban design in grandiose terms, ascribing to it an ambitious and comprehensive scope that spanned various scales and domains. His vision encompassed everything from regional and national planning to the intricate design of street furniture, encompassing urban renewal initiatives, historic preservation efforts, and the exercise of aesthetic control. This expansive conceptualization underscored the far-reaching implications and diverse facets of urban design.

Kevin Lynch (1960), in his seminal work “The Image of the City,” employed the terms “urban design” and “city design” interchangeably, reflecting the intertwined nature of these concepts. However, in his later work, Lynch advocated for a broader and more expansive interpretation of city design, encompassing a wide range of activities from preparing regional access studies to revitalizing public squares (1981). This evolution in Lynch’s thinking mirrored the growing recognition of urban design’s multidimensional nature.

Jane Jacobs (1964), a pioneering voice in urban theory, cautioned against the reductionist approach of treating cities and neighborhoods as mere architectural problems. She asserted, “To approach the city… or neighborhood as if it were a larger architectural problem… is to substitute art for life.” This critique highlighted the need for urban design to transcend aesthetic considerations and engage with the lived experiences and dynamics of urban environments.

Frederick Gibberd (1953) offered a more traditional and aesthetically-oriented definition, characterizing the purpose of town design as “to see that (the urban) composition not only functions properly, but it is pleasing in appearance.” This perspective emphasized the visual and compositional aspects of urban design, reflecting the enduring influence of design traditions rooted in architectural and artistic principles.

In contrast, Buchanan (1988) adopted a more holistic and experiential approach, defining urban design as “essentially about place making, where places are not just a specific space, but all the activities and events that make it possible.” This interpretation underscored the importance of considering the dynamic interplay between physical spaces and the social, cultural, and experiential dimensions that imbue them with meaning and vitality.

Edward Relph (1976) and David Canter (1977) contributed to the discourse by developing models that captured the multifaceted components of a “sense of place.” These models were later reinterpreted and expanded upon by Punter (1991), reflecting the ongoing efforts to conceptualize and articulate the complex interplay of factors that shape our experience and perception of urban environments.

Robert S. Cook (1980) portrayed urban design as a process aimed at achieving four distinct yet interrelated qualities: visual, functional, environmental, and the urban experience. This multidimensional perspective acknowledged the diverse considerations that urban designers must navigate, from aesthetic and practical concerns to environmental sustainability and the creation of meaningful and engaging urban experiences.

Ian Bentley (1985) proposed a framework of seven qualities that characterize responsive environments: permeability, variety, legibility, robustness, visual appropriateness, richness, and personalization. This set of principles highlighted the importance of designing urban spaces that are accessible, diverse, comprehensible, resilient, visually appealing, rich in experiences, and capable of fostering a sense of personal connection and ownership.

The Prince of Wales (1989) outlined a set of ten principles that he believed should guide urban design efforts, including considerations such as place, hierarchy, scale, harmony, enclosure, materials, decoration, art, signs and lights, and community. This multifaceted approach underscored the multidimensional nature of urban design, encompassing not only physical and aesthetic factors but also the integration of artistic elements and the fostering of a sense of community.

Christopher Alexander (1987) offered a thought-provoking perspective, asserting that “The task of creating wholeness in the city can only be dealt with as a process. It cannot be solved by design alone, but only when the process by which the city gets its form is fundamentally changed.” This view challenged the notion of urban design as a purely design-centric endeavor and highlighted the need for a more holistic and integrated approach that considers the broader processes and dynamics shaping urban environments.

Stephen Carr (1992) identified five common motivations that drive efforts to “make or remake public spaces”: public welfare, visual enhancement, environmental enhancement, economic development (including profit), and image enhancement. This recognition of the diverse motivations and priorities that underlie urban design projects underscored the complexity and multifaceted nature of the field, as well as the need to navigate and reconcile potentially competing interests and objectives.

Donald Appleyard (1982) recognized three distinct styles of urban design practice: development, community, and conservation, each with its own unique set of preferred projects, skills, ethical positions, and political orientations. This categorization acknowledged the diversity of approaches and priorities within the field, reflecting the varied contexts, stakeholders, and objectives that shape urban design efforts.

Kevin Lynch (1981), in a poetic and thought-provoking definition, characterized urban design as “The playful creation and strict evaluation of the possible form of something, including how it is to be made. That something need not be a physical object nor is design expressed only in drawings.” This interpretation expanded the boundaries of urban design beyond the purely physical realm, encompassing the imaginative exploration of possibilities and the rigorous evaluation of proposed forms and processes.

Conclusion

The numerous definitions and perspectives on urban design presented in this article highlight the multifaceted, interdisciplinary nature of the field. Urban design lies at the intersection of architecture, planning, sociology, environmental studies, and placemaking, among other disciplines. The definitions reveal urban design’s broad scope, spanning everything from the design of individual building facades to the creation of entire cities and regions.

While some definitions emphasize urban design’s artistic, compositional and aesthetic aspects, others underscore its role in fostering functional, sustainable, and socially engaging urban environments. The diversity of motivations driving urban design efforts, including economic development, environmental enhancement, and community building, further contributes to the richness and complexity of the field.

Urban design emerges as a dynamic and evolving practice, constantly adapting to address the multi-scalar challenges of the built environment. As cities and urban areas face new social, economic, and environmental pressures, urban design will continue to play a vital role in shaping livable, resilient, and meaningful places for years to come.

UDL Photoshop Masterclass

Decipher the secrets of Mapping and 3D Visualisation

Urban Design Lab

About the Author

This is the admin account of Urban Design Lab. This account publishes articles written by team members, contributions from guest writers, and other occasional submissions. Please feel free to contact us if you have any questions or comments.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “