Egypt’s Urban Gamble: The Making of a Capital From Scratch

Egypt’s ambitious New Administrative Capital (NAC), located 45 kilometers east of Cairo, promises to address the city’s congestion, revitalize governance infrastructure, and signal a modern national identity. But behind the glass facades and palm-lined boulevards lies a deeper dilemma of urban priorities. Spearheaded by the government and military-linked developers, the NAC is designed to house 6.5 million residents and a new government core—yet it remains largely inaccessible to the average Egyptian.

Critics argue the NAC diverts funds from existing cities like Cairo, Alexandria, and Aswan, where informal housing, infrastructure decay, and socio-spatial inequalities demand urgent attention. Instead of healing urban dysfunctions, the NAC may deepen them—pushing administrative elites into gated enclaves while the rest of Egypt’s urban population remains underserved. The project is also emblematic of a global trend in top-down, image-driven planning, often disconnected from public needs.

Cairo’s Urban Crisis and the Birth of a New Capital

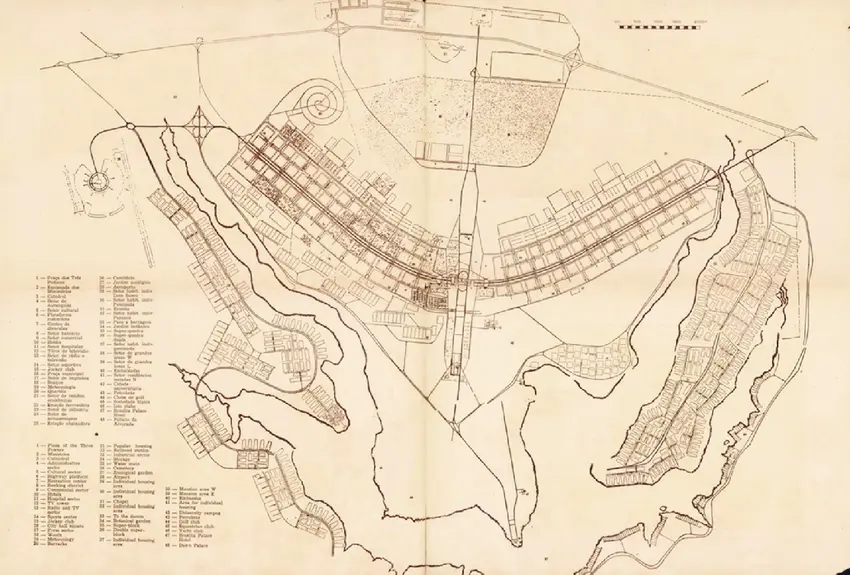

Cairo, one of the world’s oldest and most populous cities, faces an escalating urban crisis. With over 20 million residents, the metropolis struggles with severe congestion, housing shortages, and overburdened infrastructure. The Egyptian government’s solution? Build a brand-new capital in the desert. The New Administrative Capital (NAC), announced in 2015, is positioned as a bold move to decongest Cairo and modernize Egypt’s administrative functions. The 700-square-kilometer megaproject is planned to host the presidential palace, parliament, ministries, embassies, and housing for 6.5 million people. Yet, the NAC’s vision raises critical questions about resource allocation, class segregation, and state priorities in urban development.

Source: Website Link

Who Is the NAC For? The Issue of Affordability

Despite its promises, the NAC appears to cater primarily to upper-middle-class professionals and government elites. Housing units start at prices far beyond the reach of most Egyptians, in a country where nearly one-third of the population lives below the poverty line. Developers argue that luxury sales subsidize affordable housing, but few credible mechanisms exist to enforce this. Gated compounds, foreign investments, and glossy high-rises dominate promotional materials, reinforcing the image of an exclusive enclave. The affordability gap echoes similar critiques of Egypt’s satellite cities from the 1990s, many of which remain underpopulated due to economic mismatch. The NAC thus risks becoming an island of opulence surrounded by urban neglect.

Source: Website Link

Megaproject Urbanism: Lessons from Other New Capitals

Egypt’s NAC joins a lineage of new capitals—Brasília in Brazil, Abuja in Nigeria, and Naypyidaw in Myanmar—designed to symbolize progress and reorient national identity. While Brasília succeeded in showcasing modernist architecture, it failed to achieve social equity, with workers pushed to distant suburbs. Naypyidaw remains notoriously empty. These examples suggest that shifting political power doesn’t necessarily translate to democratic urbanism. NAC echoes these patterns: a capital born of spectacle rather than citizen participation. Moreover, Egypt’s approach to urbanism, where large-scale projects are handed to military-backed firms, reflects a planning model that privileges image over inclusion.

Source: Website Link

Sustainability Concerns in a Desert Megacity

Sustainability claims for NAC include smart infrastructure, green spaces, and solar integration. However, building a city in the desert raises questions about water scarcity, energy use, and climate resilience. Egypt faces mounting environmental threats, including water stress from Nile disputes and rising temperatures. The NAC’s development involves enormous material and ecological costs—expanding asphalt highways, artificially irrigated landscapes, and imported construction materials. Critics argue that sustainable retrofits in Cairo would yield better environmental outcomes than creating a new city from scratch. The sustainability narrative appears more as branding than reality—mirroring global critiques of greenwashed megaprojects.

Source: Website Link

Militarized Urbanism and Lack of Transparency

The NAC’s execution is tightly controlled by military-run agencies, such as the Armed Forces Engineering Authority and the Administrative Capital for Urban Development (ACUD). This centralization, while efficient for construction, sidelines public consultation, local planners, and civil society. Egypt’s planning system has long suffered from opacity, but the NAC elevates it to new levels—decisions are top-down, financials are undisclosed, and land allocations lack transparency. In a context of shrinking civic space and increasing surveillance, the new capital risks becoming an urban reflection of authoritarian control. It raises the question: what kind of governance is being spatially encoded into this new city?

Source: Website Link

Conclusion

Cairo’s New Administrative Capital stands at the intersection of power, technology, and spectacle. While the city promises streamlined governance and high-tech urban living, its execution reflects a deeper trend in global urbanism—where political legitimacy and image-making often override public need. The project may succeed in relocating administrative functions and attracting global investors, but it leaves open concerns about urban justice, displacement, and democratic participation. In an era when cities must respond to climate crises, housing shortages, and rising inequalities, NAC reveals the risks of pursuing urban grandeur at the expense of social and ecological balance. Egypt’s urban future must be planned not only from above but also from within its people and places.

References

- Allam, Z. (2020). Cities and the Digital Revolution: Aligning Technology and Humanity. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Barthel, P. A., & Vignal, L. (2022). New cities in the Arab world: Smart cities in the making? Built Environment, 48(1), 68–84.

- Sims, D. (2010). Understanding Cairo: The Logic of a City Out of Control. American University in Cairo Press.

- Elshahed, M. (2022). Cairo Since 1900: An Architectural Guide. American University in Cairo Press.

- Farha, M. (2021). Authoritarian Urbanism in the Arab Region. Urban Studies, 58(2), 367–385.

- Elsheshtawy, Y. (2019). Temporary Cities: Resisting Transience in Arabia. Routledge.

- Cairo Scene. (2023). What We Know About Egypt’s New Administrative Capital. Retrieved from https://www.cairoscene.com

- Guardian. (2023). Egypt’s New Capital and the Urban Displacement Debate. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com

- Urban Gateway. (2024). Smart Cities or Smart for Some? Retrieved from https://www.urbangateway.org

Muhammad Ovais Kashif

About the author

Muhammad Ovais Kashif is a researcher and architectural designer from Karachi with a focus on urban morphology, public space, and speculative urban futures. He is currently contributing to the Urban Design Lab’s research initiatives, where he investigates emerging spatial paradigms through writing and case-based analysis.

Related articles

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “