Emerging Technologies Reshaping Urban Planning

Emerging technologies are rapidly transforming how cities are planned, managed, and governed. Tools like digital twins, artificial intelligence (AI), and blockchain are reshaping urban planning by enabling more data-driven, efficient, and inclusive approaches to designing and governing urban spaces.

Digital twins—real-time virtual replicas of physical environments—allow cities to simulate and test various planning scenarios, improving decision-making and transparency. Singapore’s Virtual Singapore initiative is a leading example, offering dynamic simulations to support urban policy and citizen engagement.

AI enhances planning through predictive modelling, pattern recognition, and optimisation, as seen in cities like Barcelona and Helsinki. AI also plays a key role in identifying spatial inequalities and targeting interventions, though concerns remain around algorithmic bias and data ethics.

Blockchain brings transparency and trust to governance processes. It has been piloted for secure land tenure in informal settlements and for participatory budgeting platforms in cities like Paris, ensuring that decisions are traceable and tamper-proof.

However, technology alone is not inherently inclusive. Its benefits depend on how it’s implemented, who is involved, and whose data is used.

Digital twins, artificial intelligence (AI), and blockchain

In an era defined by rapid technological advancement and escalating urban challenges, the field of urban planning is undergoing a profound transformation. Emerging technologies such as digital twins, artificial intelligence (AI), and blockchain are not just tools of efficiency—they are reshaping how cities are designed, managed, and governed. More importantly, they hold the potential to make urban governance more inclusive, transparent, and participatory.

The Digital Twin Revolution in Urbanism

At the forefront of this transformation is the concept of digital twins—real-time, virtual replicas of physical environments. In urban planning, a digital twin is essentially a living, 3D model of a city, constantly updated with data from sensors, satellites, and other sources. It mirrors the physical city and its systems, such as transport networks, energy grids, and stormwater infrastructure, allowing planners to test scenarios and forecast outcomes before implementing real-world changes. These dynamic models enable simulations of how a new housing development might affect traffic or how different flood responses play out during extreme weather events. The city of Singapore is a global pioneer in this field. Through its Virtual Singapore initiative, the government has developed a comprehensive digital twin to support policy making and citizen engagement (Mekuria et al., 2019).

As Batty (2018) notes, digital twins are ushering in a “new era of model-driven governance” where decisions are no longer made behind closed doors but through transparent, data-supported dialogue.

Source: Website Link

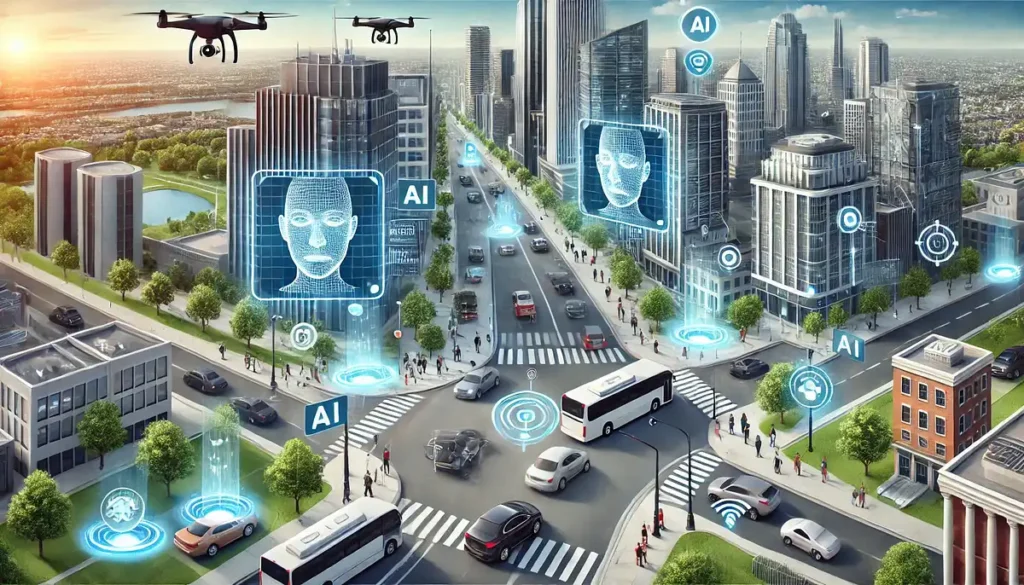

Artificial Intelligence: The New Urban Analyst

Artificial Intelligence is another force transforming urban planning. Machine learning algorithms can process vast datasets—from satellite imagery to mobility data—and extract patterns that were previously invisible to the human eye. In Barcelona, AI tools have been used to optimise traffic flows, reducing emissions and improving air quality (Alonso et al., 2022). Meanwhile, cities like Helsinki are applying AI in land-use simulations, helping planners evaluate multiple development scenarios based on environmental and social metrics (European Commission, 2024).

But AI’s potential goes beyond optimisation. It can play a powerful role in identifying inequality and targeting interventions. For example, predictive models can flag areas most vulnerable to climate risk or social exclusion, enabling cities to allocate resources more equitably. Yet, as Crawford (2021) warns, AI is not neutral—it reflects the biases of its creators and the data it consumes. Inclusive urban governance must therefore involve communities not just as users of AI, but as co-creators of the data and models that shape their futures.

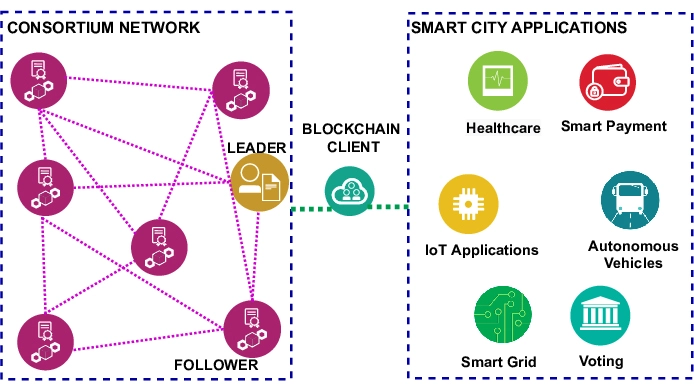

Blockchain and the Promise of Transparency

While less visually dazzling than AI or digital twins, blockchain technology may hold the key to a more transparent and accountable urban future. At its core, blockchain is a decentralised ledger that records transactions in a secure, tamper-proof way. In urban governance, it offers radical potential: securing land registries, managing participatory budgeting, or ensuring fair distribution of public subsidies (UN-Habitat, 2023).

One notable example comes from South Africa, where blockchain is being explored to secure informal land tenure. By recording ownership claims on a public ledger, residents in informal settlements can gain recognition without the bureaucracy of formal title deeds (Lemieux et al., 2019). Similarly, the city of Paris has piloted blockchain platforms for participatory budgeting, ensuring that citizen votes are traceable and cannot be manipulated.

Blockchain’s value lies in its ability to build trust, a scarce but crucial commodity in many urban governance contexts. As Sassen (2020) emphasises, the future of inclusive governance depends not only on the availability of data but on the legitimacy of the institutions that manage it. Blockchain may help provide that legitimacy.

Toward Inclusive City Governance

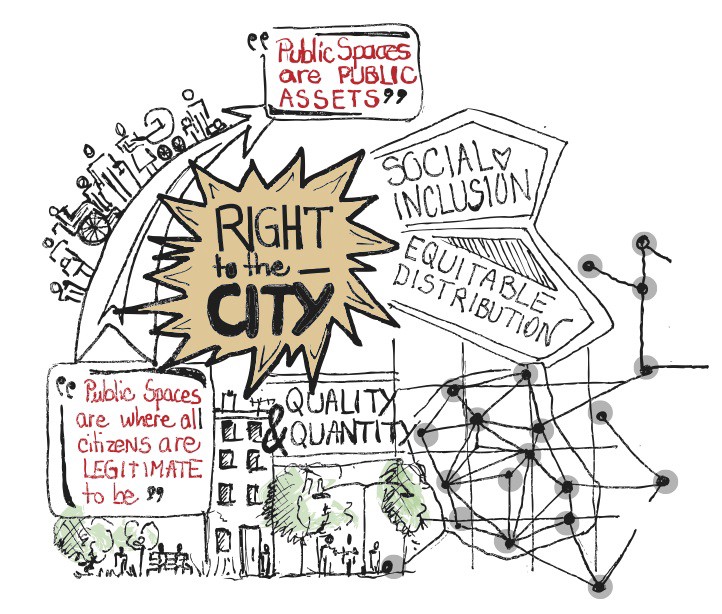

Technology, however, is not inherently inclusive. While digital twins and AI promise efficiency, they can also reinforce existing inequalities if deployed without critical reflection. Inclusivity in urban governance is about who gets to participate, whose data is used, and whose needs are prioritised.

Emerging platforms are responding to this challenge. In Amsterdam’s “Tada Manifesto,” city officials, technologists, and civil society groups agreed on guiding principles for responsible digital city-making: inclusivity, transparency, and control over personal data (City of Amsterdam, 2020). Similarly, the European initiative DECODE empowers citizens to control their own data through decentralised technology, ensuring digital participation doesn’t come at the cost of privacy.

Participatory planning is also being enhanced through immersive tech. In Bristol, for example, augmented reality (AR) is used in public workshops to help residents visualise proposed developments. Rather than deciphering 2D maps, participants can walk through virtual streetscapes, making planning processes more accessible and intuitive (Goulding et al., 2021).

Moreover, platforms like Decidim in Barcelona—an open-source digital democracy tool—enable thousands of residents to propose, debate, and vote on policies in real time. This model blends technology with civic empowerment, showing that digital infrastructure can support—not replace—democratic institutions (Barcelona City Council, n.d.).

The Challenge of Data Justice

Despite these advancements, the increasing reliance on digital technologies raises critical questions around data justice. Who owns the data that cities rely on? Who profits from it? And how do we prevent surveillance or exclusion?

As Taylor (2017) argues, “smart cities” must not just be technologically advanced—they must be ethically grounded. The use of AI and digital platforms in public space planning must come with safeguards: open-source code, inclusive governance boards, and mechanisms for redress when systems fail.

Furthermore, as cities collect more personal and behavioural data, protecting citizens’ rights becomes paramount. This is especially true for marginalised groups, who are often the most surveilled and least consulted.

Conclusion

Emerging technologies are redefining what cities can be. They allow planners to anticipate future scenarios, optimise urban systems, and engage citizens in entirely new ways. But these tools are only as inclusive as the processes and values behind them.

To ensure that digital transformation in urban planning truly benefits all, we must prioritise transparency, equity, and participation at every stage. That means involving communities in data governance, designing technologies that are accessible and inclusive, and building digital trust into the foundations of urban development.

The future city is not just smart—it’s fair, inclusive, and human-centred. And getting there depends not only on innovation, but on our collective ability to wield it with responsibility and care.

References

- Alonso, J., et al. (2022). Urban AI: Planning Smarter Cities. Journal of Urban Technology, 29(3), 1–18.

- Barcelona City Council. (n.d.) Decidim: A digital platform for participatory democracy. [online] Available at: https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/digital/en/technology-accessible-everyone/accessible-and-participatory/accessible-and-participatory-5 [Accessed 12 Jun. 2025].

- Batty, M. (2018). Digital Twins. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science, 45(5), 817–820.

- City of Amsterdam. (2020). Tada: Data Disclosed – Manifesto for Responsible Digital Cities. Retrieved from https://tada.city

- Crawford, K. (2021). Atlas of AI. Yale University Press.

- European Commission. (2024) Reimagining Helsinki: Participatory urban planning with generative AI. [online] Interoperable Europe. Available at: https://interoperable-europe.ec.europa.eu/collection/public-sector-tech-watch/reimagining-helsinki-participatory-urban-planning-generative-ai [Accessed 12 Jun. 2025].

- Goulding, J., et al. (2021). Immersive Urbanism: AR Tools for Inclusive Planning. Cities, 112, 103144

- Lemieux, V. L., et al. (2019). Blockchain for Secure Land Registries. Government Information Quarterly, 36(3), 487–496.

- Mekuria, F., et al. (2019). Virtual Singapore: A Smart City Digital Twin. Future Cities and Environment, 5(1), 1–12.

- Sassen, S. (2020). Who Owns the City? The Role of Data and Capital in Urban Space. Urban Studies, 57(10), 2023–2040.

- Taylor, L. (2017). What is Data Justice? The International Journal of Communication, 11, 755–772.

- UN-Habitat. (2023) Blockchain for urban development: Guidance for urban managers. [online] United Nations Human Settlements Programme. Available at: https://unhabitat.org/blockchain-for-urban-development-guidance-for-urban-managers [Accessed 12 Jun. 2025].

Aleksander Korzjukov

About the Author

Aleksander is an aspiring urban planner with a Master’s degree in Environmental and Infrastructure Planning and a Bachelor’s in Spatial Planning and Design from the University of Groningen. His academic work focuses on climate adaptation, nature-based solutions, and inclusive urban development. He has researched stormwater management in informal settlements and contributed to projects on tiny housing, green roofs, and community-led design. With experience in both spatial analysis and participatory planning, Aleksander is passionate about bridging the gap between research and practice to create sustainable, resilient, and people-centred urban environments.

Related articles

Social Capital Theory in Urban Design

Third Place Theory: Creating Community Spaces

Book Review: Transparency by Colin Rowe and Robert Slutzky

5-Days UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

14th-18th July 2025

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “