Evolution of Christmas Celebrations in Urban Spaces

A Historical Perspective: Evolution of Christmas Celebrations in Urban Spaces

The celebration of Christmas in urban spaces has indeed experienced a profound transformation, as illuminated by various academic insights. Carolyn Sigler, in “‘I’ll Be Home for Christmas’: Misrule and the Paradox of Gender in World War II-Era Christmas Films,” notes that Christmas has transitioned from a disorderly, carnivalesque celebration to a more private, family-centered event, symbolizing a shift from public revelry to domestic tranquility (Sigler, 2005). J. Schmalzbauer, in “Commercialism and Consumerism,” further elaborates on this evolution, tracing the journey from pre-commercial folk celebrations to the modern era of commercialization, consumerism, and mass-produced decorations, highlighting the profound impact of commercial forces on the holiday (Schmalzbauer, 2020).

Francesca Silano, in “Russia” from “The Oxford Handbook of Christmas,” reflects on how the Christmas tree (elka) and the celebration itself have evolved in Orthodox Russia, offering a unique perspective on the cultural and temporal shifts within urban and rural settings (Silano, 2020). B. Prideaux and P. Glover, in their study “‘Santa Claus is Coming to Town’ – Christmas Holidays in a Tropical Destination,” emphasize the creation of an authentic “Christmas feel” in urban spaces through decorations, nativity scenes, and special foods, illustrating the adaptability of Christmas traditions to various urban environments (Prideaux & Glover, 2015).

These scholarly perspectives collectively underscore the dynamic nature of Christmas celebrations in urban spaces, reflecting broader social, cultural, and technological changes. From its modest beginnings to the spectacular, diverse celebrations witnessed today, the evolution of Christmas in cities worldwide offers a rich tapestry of history, tradition, and cultural adaptation.

Early Celebrations in Medieval Cities

The early celebrations of Christmas in medieval cities were a vibrant blend of religious and secular traditions, as highlighted by various academic studies. K. Ihnat, in “The Middle Ages” from “The Oxford Handbook of Christmas,” describes medieval Christmas as a time filled with merriment and miracles, characterized by unique practices like the feasts of fools, boy bishops, and elaborate liturgical dramas (Ihnat, 2020). This period saw a fascinating interplay between sacred observances and festive, often carnivalesque, public celebrations.

In Western Europe and North America between the 16th and 18th centuries, as noted by K. Wheeler in “The Reformation and Early Modern Periods,” Christmas celebrations included gift-giving, hospitality, feasting, singing, and decorating with greenery and trees, indicating a rich tapestry of traditions that have evolved over time (Wheeler, 2020). G. Kahveci, in “Traditional usage of the fir species: fir as a Christmas tree from Middle Asia to Europe,” points out the influence of Pagan celebrations on these traditions, such as the Turkish “Nardugan” (wintry solstice holiday), which involved decorating a tree called “Akçam” (white pine) (Kahveci, 2012).

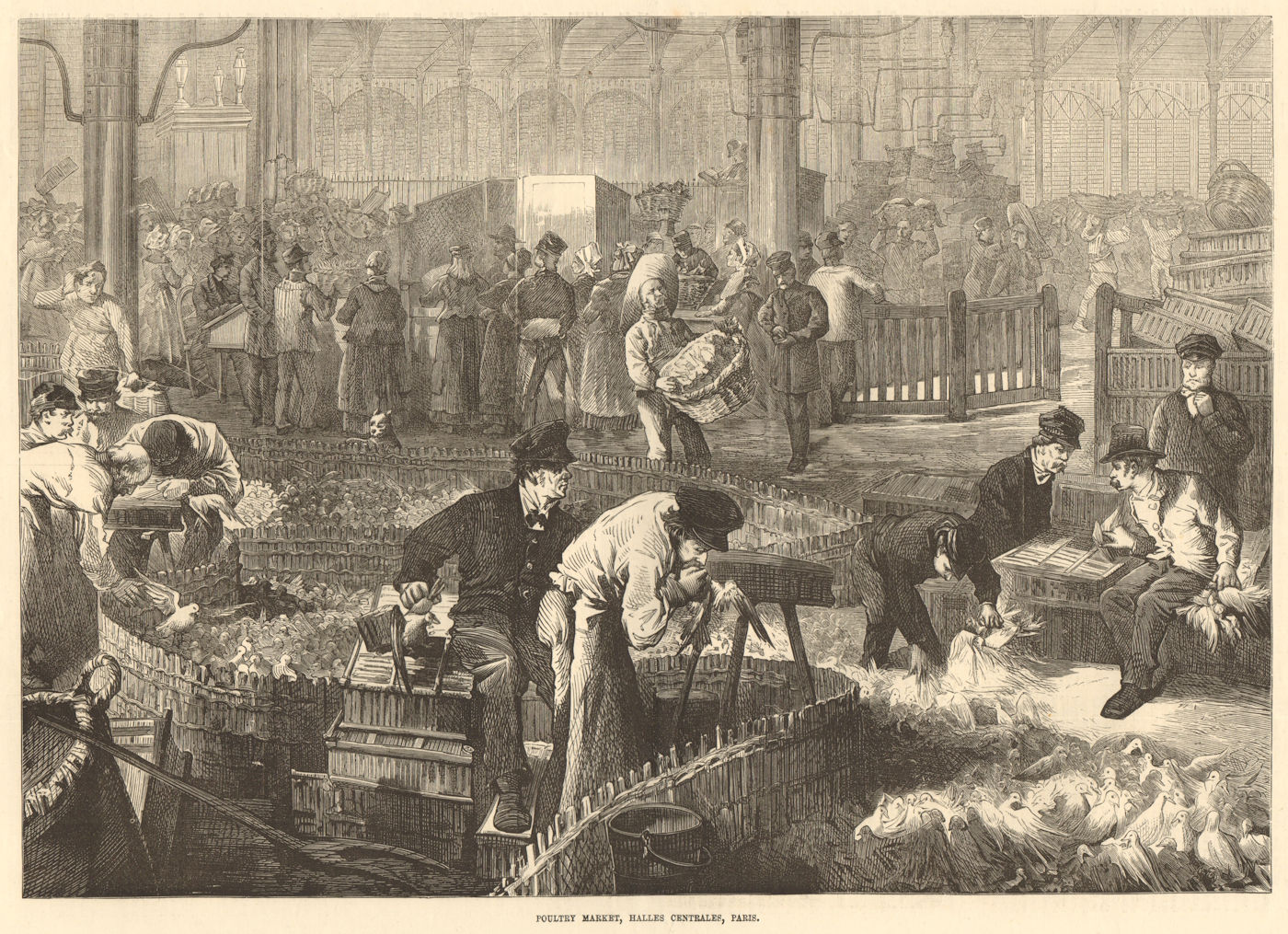

The tightly packed streets of medieval cities, especially the market squares, became hubs for these festivities. The communal aspect of Christmas was evident in the public spaces where people gathered for carol singing, dances, and the early forms of Christmas markets. These gatherings were not just about religious observance but also about community bonding and secular enjoyment.

.jpg)

The 17th and 18th Centuries: A Time of Change

During the 17th and 18th centuries, Christmas celebrations in urban areas underwent significant changes, influenced by religious, social, and cultural shifts. The Reformation played a crucial role in altering the nature of these celebrations, particularly in Protestant regions. Markus Rathey, in “CARNIVAL AND SACRED DRAMA: SCHÜTZ’S CHRISTMAS HISTORIA AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF CHRISTMAS IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY,” discusses how the Reformation led to a transformation in Christmas celebrations, shifting from external displays of piety to more internalized devotional practices (Rathey, 2017).

In contrast, in Catholic regions, Christmas retained much of its festive spirit. K. Wheeler, in “The Reformation and Early Modern Periods,” notes that while Christmas celebrations continued in both Protestant and Catholic countries, they often changed from their medieval forms (Wheeler, 2020). This period saw the emergence of many traditions that are now synonymous with Christmas, such as the decoration of Christmas trees and the giving of gifts.

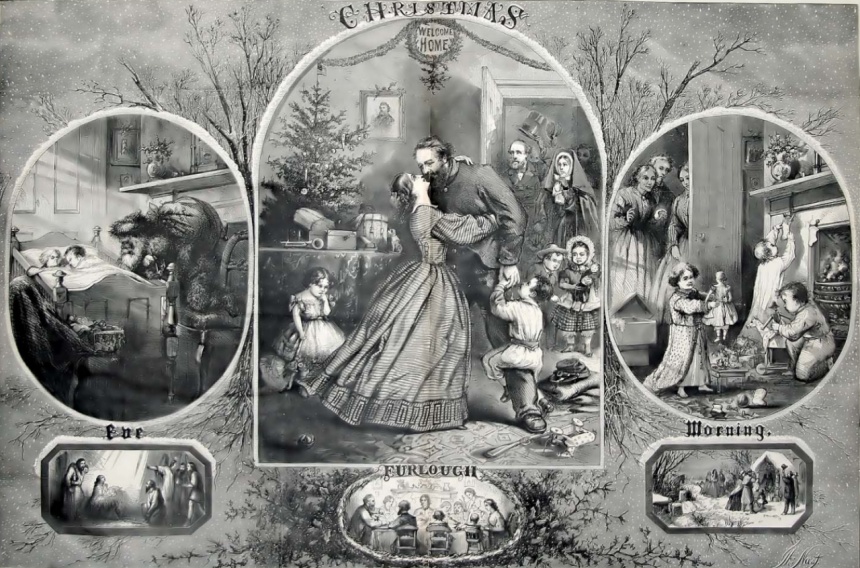

The domestication of Christmas in the 19th century, as described by Timothy Larsen in “The Nineteenth Century” from “The Oxford Handbook of Christmas,” further illustrates the evolution of the holiday. This era saw a focus on home and family, with new traditions like the Christmas tree and the Christmas card becoming central to the celebration (Larsen, 2020).

These changes reflect the broader social and cultural dynamics of the time. The 17th and 18th centuries were a period of transition for Christmas celebrations in urban areas, moving away from the more communal, public festivities of the medieval period to more private, family-centered celebrations that laid the groundwork for many of the traditions we associate with Christmas today.

The 19th Century: The Birth of the Modern Christmas

The 19th century marked a significant transformation in the celebration of Christmas in urban areas, influenced by various social, economic, and cultural factors. The Industrial Revolution and rapid urbanization played pivotal roles in reshaping Christmas traditions.

According to Timothy Larsen in “The Nineteenth Century” from “The Oxford Handbook of Christmas,” Christmas during this period experienced a significant shift towards domestication, focusing more on home and family. This era introduced new traditions like the Christmas tree and the Christmas card (Larsen, 2020). The rise of the middle class and the new urban poor influenced how Christmas was celebrated, with a growing emphasis on family-centric festivities.

Carolyn Sigler, in “I’ll Be Home for Christmas”: Misrule and the Paradox of Gender in World War II-Era Christmas Films,” discusses how the unruly, carnivalesque celebration of Christmas in earlier centuries transformed into a more private, family-centered celebration, reflecting the changing middle-class domesticity (Sigler, 2005).

The public celebration of Christmas, however, did not vanish. Cities began to play a more active role in Christmas festivities. Municipal Christmas trees became common in public squares, and the late 19th century saw the introduction of the first electrically lit public Christmas trees, showcasing the era’s technological advancements.

Department stores, emerging as a new urban phenomenon, contributed significantly to the urban Christmas experience. As Hilary Naomi Raats points out in “Visualizing the Victorian Christmas: Evolving Iconography and Symbolism in the Wake of Nineteenth-Century Commercialism,” the expansion of commercial opportunities led to new symbolism in Christmas celebrations, influenced by rising consumerism and material culture (Raats, 2017). Elaborate Christmas window displays and Santa Claus parades became a staple of the urban shopping experience during the holiday season, drawing crowds and transforming the urban landscape.

Thus, the 19th century was indeed the birth of the modern Christmas, marked by a blend of domestic traditions and public, urban celebrations, influenced by the social and economic changes of the time.

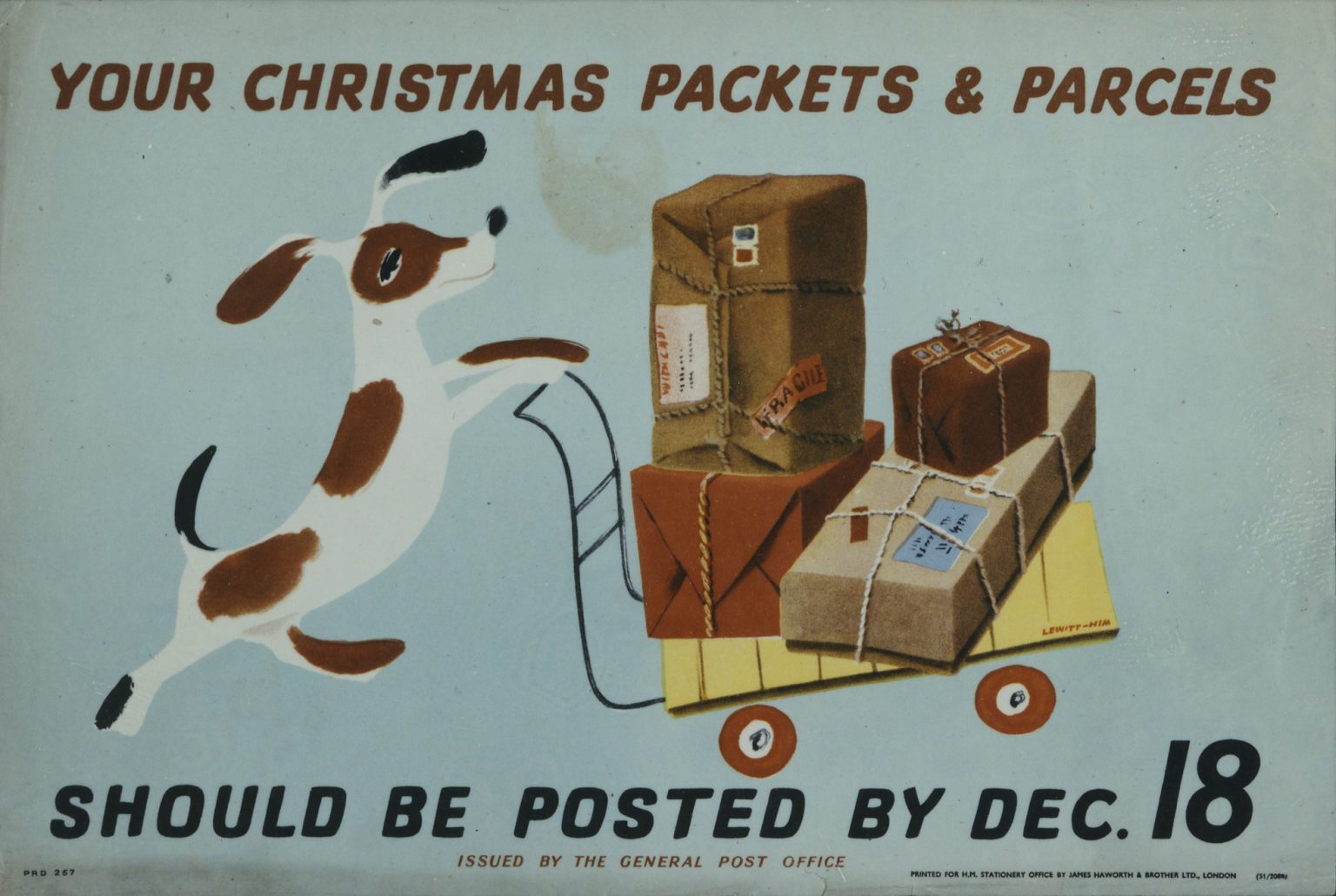

The 20th Century: Commercialization and Spectacle

The 20th century witnessed a dramatic transformation in the celebration of Christmas in urban areas, characterized by heightened commercialization and spectacle. This period saw Christmas becoming a key retail event, with cities worldwide adorning their stores and streets with lights and decorations to attract shoppers.

W. Waits, in “The Modern Christmas in America: A Cultural History of Gift Giving,” discusses how industrialization brought inexpensive, mass-produced items to Christmas, leading to a backlash from reformers in the early 20th century. This response contributed to the modern holiday’s formation, intertwining commercialism with traditional celebrations (Waits, 1992).

The Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, first held in 1924 in New York City, is a prime example of this blend of commercial spectacle and public celebration. As Penne L. Restad notes in “Christmas in America: A History,” New York became an epicenter of the holiday, with figures like Washington Irving and Clement Clarke Moore inventing the modern Santa Claus, further embedding commercial elements into the holiday (Restad, 1995).

Urban Christmas celebrations also became more inclusive during this time. Municipalities began to recognize the diverse cultural backgrounds of their citizens, incorporating a variety of traditions and symbols into public displays and events. This inclusivity reflected the evolving social fabric of urban centers.

Carolyn Sigler, in “I’ll Be Home for Christmas”: Misrule and the Paradox of Gender in World War II-Era Christmas Films,” highlights how Christmas became a commercialized spectacle during World War II, exemplifying the invention of tradition and relocating the holiday from the street to the parlor (Sigler, 2005).

The commercialization of Christmas was not without its critics. Christopher Ferguson, in “The Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries” from “The Oxford Handbook of Christmas,” discusses the increasing commercialization of Christmas in the 20th century and the concerns it raised about the holiday’s secularization and disputed character (Ferguson, 2020).

Overall, the 20th century marked a significant shift in the celebration of Christmas in urban areas, with commercialization and spectacle playing a central role in shaping the holiday’s modern form.

Post-War Era and the Rise of Urban Christmas Markets

In the post-World War II era, Christmas markets experienced a significant resurgence, particularly in Europe, as part of a broader interest in reviving traditional Christmas celebrations. This revival was partly driven by a desire to restore normalcy and community spirit after the war.

D. Spennemann and Murray Parker, in “The Changing Face of German Christmas Markets: Historic, Mercantile, Social, and Experiential Dimensions,” discuss how Christmas markets in Germany transformed from primarily mercantile operations to experiential events. This transformation began in the 1930s and continued post-war, incorporating social and experiential dimensions that went beyond mere commerce (Spennemann & Parker, 2021).

J. Stobart and Ilja Van Damme, in “Introduction: markets in modernization: transformations in urban market space and practice, c. 1800 – c. 1970,” note that despite modernization, Christmas markets in urban areas continued to be vibrant parts of various towns and cities across the globe (Stobart & Van Damme, 2015). These markets became a way to celebrate local crafts, food, and traditions, offering a counterpoint to the commercialization seen in other aspects of urban Christmas celebrations.

Grzegorz Kromka, P. Kurowski, and Agnieszka Kudłacz, in “The Christmas Market as an Attractive Tourist Product of Cracow,” highlight the attractiveness of these markets as tourism products. For instance, Cracow’s Christmas Market was highly recommended by visitors and considered the most attractive trade event in the city center (Kromka, Kurowski, & Kudłacz, 2018).

Aurélie Broeckerhoff and C. Galalae, in “Christmas markets – marketplace icon,” discuss the iconicity of Christmas markets, facilitated by their openness across historical and cultural contexts and their ability to incorporate various complex meanings (Broeckerhoff & Galalae, 2020).

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/electric-christmas-lights-1890s-3000-3x2gty-583f604a3df78c0230c9bca3.jpg)

The Late 20th and Early 21st Centuries: Technological Innovations and Sustainability Concerns

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, Christmas celebrations in urban areas have been significantly influenced by technological innovations and growing sustainability concerns.

Technological advancements have led to more elaborate and interactive light displays, contributing to the spectacle of urban Christmas celebrations. Cities around the world compete to present the most spectacular holiday decorations, drawing tourists and boosting local economies. Chai-Lee Goi, in “The impact of technological innovation on building a sustainable city,” discusses how technological innovation has changed the overall effectiveness and benevolence of sustainable development in urban areas, focusing on environmental stewardship, social development, and economic progress (Goi, 2017).

However, this period has also seen a growing awareness of the environmental impact of these celebrations. Many cities are now striving to balance the festive spirit with sustainability. This includes using energy-efficient lighting, promoting eco-friendly decorations, and encouraging recycling and waste reduction during holiday events. J. Ahern, in “From fail-safe to safe-to-fail: Sustainability and resilience in the new urban world,” highlights the importance of urban resilience strategies, including multifunctionality, redundancy, modularization, diversity, multi-scale networks, and adaptive planning and design, which are crucial for sustainable urban development (Ahern, 2011).

The evolution of Christmas celebrations reflects a broader trend in urban areas towards embracing technological innovation while also recognizing the need for sustainable practices. This dual focus ensures that the festive spirit of the holiday season can be enjoyed by current and future generations, with minimal environmental impact.

Conclusion

Today, Christmas in urban spaces is a multifaceted celebration, reflecting the diverse, dynamic nature of city life. From the Christmas tree lighting in Rockefeller Center to the traditional markets of European cities, and the Southern Hemisphere’s beachside Christmas festivities, the ways in which we celebrate Christmas in urban areas continue to evolve.

As we look to the future, the challenge for cities will be to maintain the magic and wonder of Christmas while adapting to changing social values and technological possibilities. The evolution of Christmas celebrations in urban spaces is not just a story of changing decorations and traditions; it’s a reflection of the ongoing story of our cities themselves – spaces of constant change, innovation, and community spirit

References

- Sigler, C. (2005). “‘I’ll Be Home for Christmas’: Misrule and the Paradox of Gender in World War II-Era Christmas Films.” The Journal of American Culture, 28, 345-356.

- Schmalzbauer, J. (2020). “Commercialism and Consumerism.” DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198831464.013.44.

- Silano, F. (2020). “Russia.” The Oxford Handbook of Christmas. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198831464.013.37.

- Prideaux, B., & Glover, P. (2015). “‘Santa Claus is Coming to Town’ – Christmas Holidays in a Tropical Destination.” Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 20, 955 – 970.

- Ihnat, K. (2020). “The Middle Ages.” The Oxford Handbook of Christmas.

- Wheeler, K. (2020). “The Reformation and Early Modern Periods.”

- Kahveci, G. (2012). “Traditional usage of the fir species: fir as a Christmas tree from Middle Asia to Europe.” Kastamonu University Journal of Forestry Faculty, 12, 8-14.

- Rathey, M. (2017). “CARNIVAL AND SACRED DRAMA: SCHÜTZ’S CHRISTMAS HISTORIA AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF CHRISTMAS IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY.” Early Music History, 36, 159-191.

- Wheeler, K. (2020). “The Reformation and Early Modern Periods.”

- Larsen, T. (2020). “The Nineteenth Century.” The Oxford Handbook of Christmas.

- Larsen, T. (2020). “The Nineteenth Century.” The Oxford Handbook of Christmas.

- Sigler, C. (2005). “I’ll Be Home for Christmas”: Misrule and the Paradox of Gender in World War II-Era Christmas Films. The Journal of American Culture, 28, 345-356.

- Raats, H. N. (2017). “Visualizing the Victorian Christmas: Evolving Iconography and Symbolism in the Wake of Nineteenth-Century Commercialism.”

- Waits, W. (1992). “The Modern Christmas in America: A Cultural History of Gift Giving.”

- Restad, P. L. (1995). “Christmas in America: A History.”

- Sigler, C. (2005). “I’ll Be Home for Christmas”: Misrule and the Paradox of Gender in World War II-Era Christmas Films. The Journal of American Culture, 28, 345-356.

- Ferguson, C. (2020). “The Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries.” The Oxford Handbook of Christmas.Spennemann, D., & Parker, M. (2021). “The Changing Face of German Christmas Markets: Historic, Mercantile, Social, and Experiential Dimensions.” Heritage.

- Stobart, J., & Van Damme, I. (2015). “Introduction: markets in modernization: transformations in urban market space and practice, c. 1800 – c. 1970.” Urban History.

- Kromka, G., Kurowski, P., & Kudłacz, A. (2018). “The Christmas Market as an Attractive Tourist Product of Cracow.” Folia Turistica.

- Broeckerhoff, A., & Galalae, C. (2020). “Christmas markets – marketplace icon.” Consumption Markets & Culture.

Urban Design Lab

About the Author

This is the admin account of Urban Design Lab. This account publishes articles written by team members, contributions from guest writers, and other occasional submissions. Please feel free to contact us if you have any questions or comments.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

Best Landscape Architecture Firms in Canada

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “