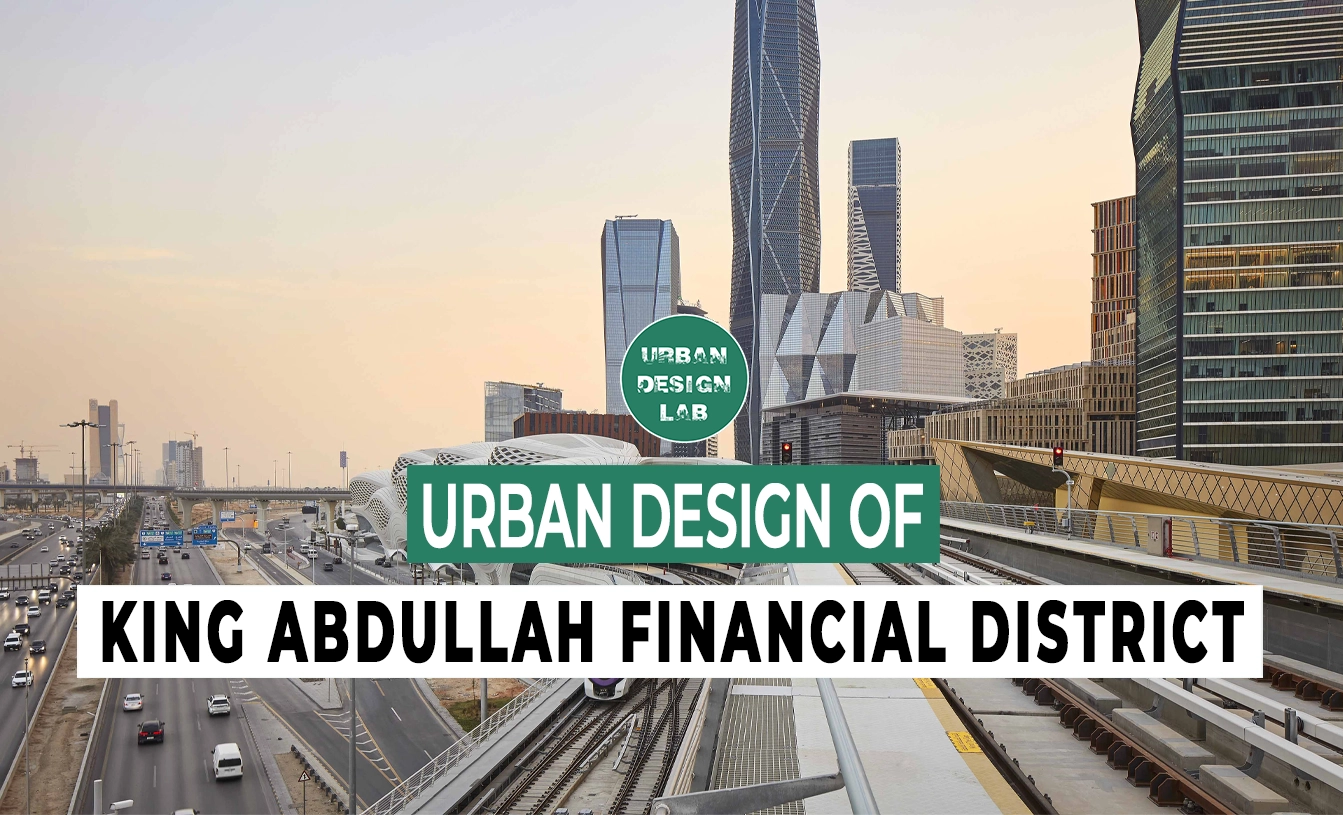

Greening Mexico City’s Paseo de la Reforma: Urban Forestry as Air Quality Intervention

Urban avenues and boulevards are more than just streets, they hold stories of tradition, culture, and people. This article dives into how Mexico City, once known as the “world’s most polluted city,” transformed into a leader of climate-sensitive urbanism. The iconic Paseo de la Reforma, which once carried stories of political reform, is now being reimagined as a green corridor that anchors urban forestry in the city.

Explore how the city went from emergency to example, confronting an air quality crisis and pollution, and learn how community and data-driven change can make a difference to ecology. By analyzing recent environmental data, policy interventions, and historical evolution, the piece focuses on how urban forestry is redefining what meaningful reform looks like in the 21st century. From Chapultepec Park’s carbon sink role to civic ecology, this case study presents the rise of Mexico City using Paseo de la Reforma as a blueprint for cities facing similar ecological stress.

Paseo de la Reforma: Historical Evolution and Contemporary Relevance

The streets of a city transform constantly and are a symbol of those who have lived in it. They tell stories of battles, celebrations, and most of all, people.

Paseo de la Reforma, Mexico’s most iconic boulevard, offers a narrative of the city’s political, cultural, and spatial evolution. Construction began in 1864 during Emperor Maximilian I’s reign in Mexico. Originally, the grand boulevard was built as an avenue to connect Chapultepec Castle with the city center. In 1872, President Sebastian Lerdo de Tejada renamed it as Paseo de la Reforma – “Promenade of the Reform.” This marked the beginning of a new era with the separation of Church and State, a symbol of Mexico’s transition to liberal, secular governance.

Today, nearly 150 years later, Paseo de la Reforma continues to stay true to its name. Once again, the iconic boulevard is a symbol of change, responding to the urgency of climate change through urban forestry, public accessibility, and climate-sensitive design.

Where Reforma once gave people a voice through political reform, today it tells a new story, one of ecological recovery through urban forestry, transforming urban health and air quality.

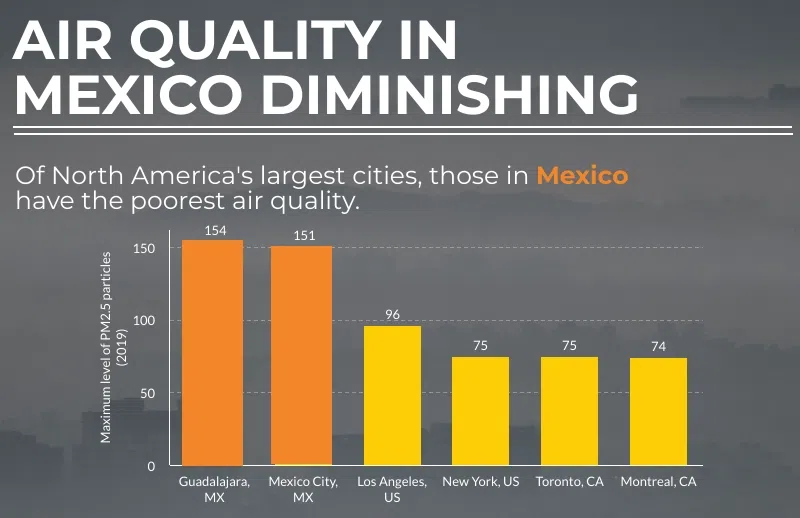

Air Quality Crisis in Mexico City

By the early 1990s, Mexico City’s air quality had deteriorated to such an extent that the United Nations referred to it as the world’s most polluted city. The byproduct of this is not just a health emergency but also triggered an economic crisis, as workers lost an average of 7.5% of their working hours on days with high levels of PM2.5, which is fine particulate matter that can penetrate deep into the lungs. While the safe limit according to the World Health Organization was an annual average of 5 µg/m³, Mexico City’s was five to six times higher.

To combat this, in 1996, the city and regional governments introduced the Management Programme to Improve Air Quality (Proaire in Spanish). This package of reforms brought down Mexico City’s air pollution from 300 (dangerously unhealthy) to 150 on its local Metropolitan Air Quality Index (IMECA). Similarly, ozone concentrations were around 500 parts per billion (ppb), which now normally range between 120 and 150 ppb.

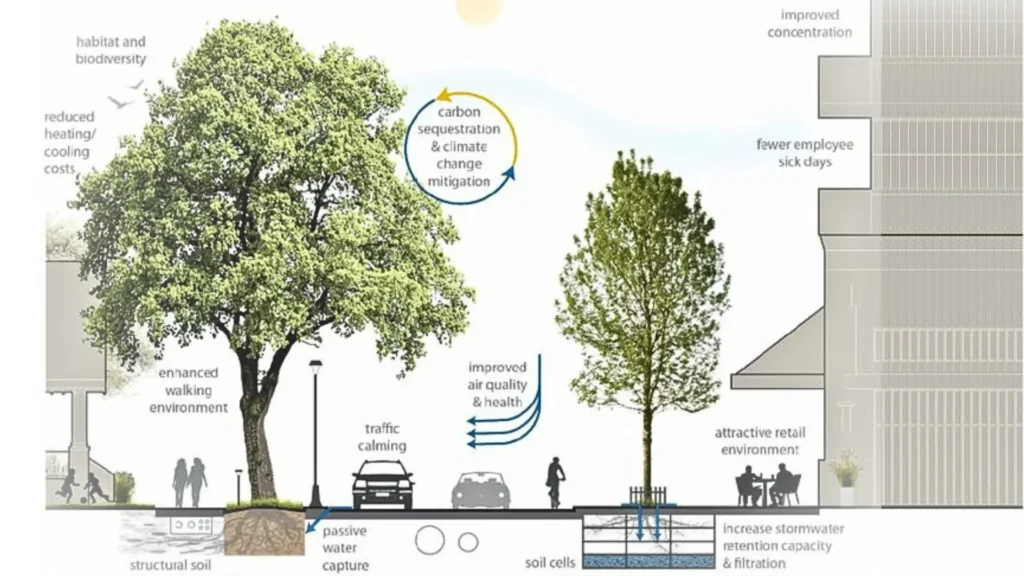

These initiatives led to improvements to finally lay a foundation for a long-term solution, urban forestry. As the City’s tree cover began to expand, it not only filtered particulate matter but also helped reduce urban heat and encouraged pedestrian mobility.

Source: Website Link

Chapultepec Park, The Ecological Anchor of Paseo de la Reforma

Chapultepec Park is one of the largest urban parks on the continent (SEDEMA Secretaría del Medio Ambiente, 2012) in the world, anchoring the western end of Paseo de la Reforma, covering 2,000 acres, acting as a vital lung for the city with various species and recreational areas for residents.

Representing 32% of Mexico City’s green areas, the park is divided into four sections, which include museums, parking lots, and artificial lakes. The forest holds the environmental and cultural richness of Mexico, with over US$32 million invested in several initiatives for the benefit of the forest. Its vital role in the city’s livability is evident from an i-Tree assessment (an internationally recognized urban forest modeling tool) conducted by the Pro Bosque de Chapultepec Trust in collaboration with other stakeholders. The Paris Peace Forum, 2023, published the following results:

- CO₂ storage: 46,200 tons

- Annual carbon sequestration: 1,438 tons

More than a park, it is an ecological preserve with forests that are home to native species, which enhances air filtration. The park’s eastern edge directly connects to Paseo de la Reforma, creating a continuous green corridor that improves urban air quality, rooted back to the heritage and culture of the city.

Biodiversity and Native Tree Selection

The science of Urban Forestry in any city is about choosing the right species of trees to develop for air quality and resilience. A cluster-based species typology is used in Mexico City as per Vazquez & Juganaru (2023), which assesses pollution levels, drought tolerance, and context-specific conditions. As a result of this project, the city was able to identify specific tree species that are tolerant to moderate pollution, thus still providing the necessary atmosphere under harsher conditions.

Paseo de la Reforma is planted with native, pollution-resistant species like ahuehuete, jacaranda, and encino, which perform multiple roles:

- Retention and absorption of PM2.5 particles and NOₓ on leaf surfaces due to their waxy cuticles and complex structures.

- Capturing and storing carbon through the dense wood of the trunks and branches.

- Creating a connectivity of biodiversity along the Reforma-Chapultepec green corridor.

Through data-driven studies, the city has been able to precisely elevate Reforma, creating a scientific understanding and proven framework for how target-specific and native tree selection can create functional ecology with long-term urban livability.

The Role of Citizens in Greening the City

Mexico City has experienced an overwhelming growth rate in the 20th century; this exponential growth has not been matched by an increase in green space. From 14% of the city consisting of green areas, the proportion dropped to 2.8% in 1910 (De Quevedo, 1935).

The city’s Urban Forestry Programme is based on these 3 fundamental goals:

- Reduce pollution

- Create recreational areas

- Improve city aesthetics

The Mexico City Urban Forest Program aims to plant millions of trees throughout the city. This focuses not only on planting new trees but also maintenance and care of existing ones. Municipal Forest Committees promoted by the Secretariate of Agriculture and Water Resources are being set up in every state of the country. Another example of citizens taking up responsibility is ecological groups like Movimiento Ecologista Mexicano (MEM), which use media to press for matters of urban forestry expansion.

Citizens’ groups raise funds through national campaigns to restore vital parks and open areas in the city, highlighting that urban forestry is not just government-driven but co-produced with communities. What makes the city’s approach to urban forestry unique is the active role of its citizens.

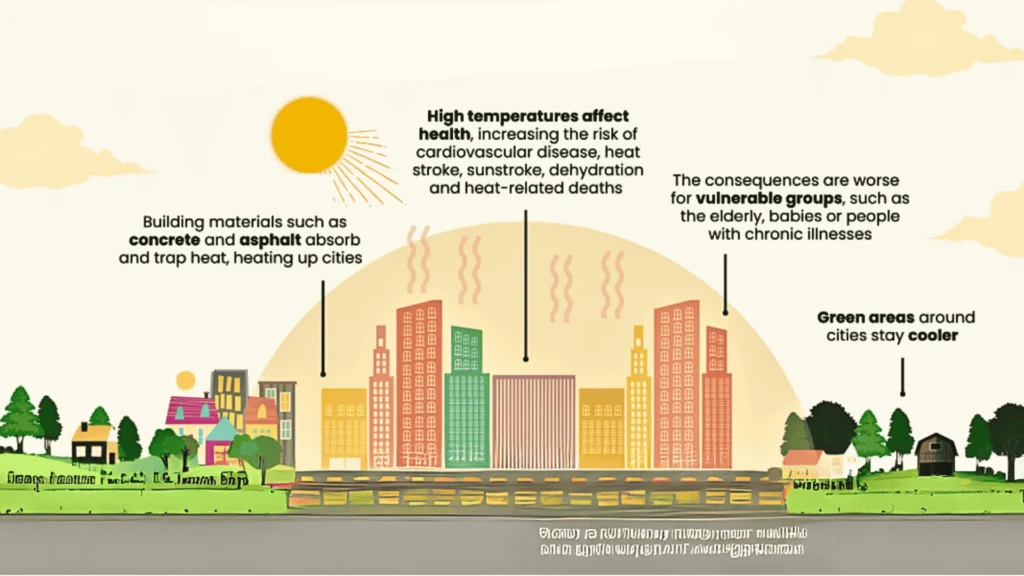

Urban Forests vs. Urban Heat Islands

Urban forestry along Paseo de la Reforma has not only improved air quality but also acts as a shield against Urban Heat Islands (UHI). For example, Chapultepec Park is 2–3 °C cooler within its boundaries on clear nights, creating a microclimate (Jauregui, 1990).

It is recognized by the World Health Organization that urban green spaces help reduce increased temperatures through shading and transpiration. The effects of urban forests extend into dense commercial and residential areas.

The science behind UHI mitigation needs to be integrated into canopy expansion strategies and data-driven species selection. These effects extend beyond thermal comfort, varying from reducing heat exposure in high-traffic zones to slowing down ozone formation. Taking all the above into consideration, Urban Forestry is a valuable tool against Urban Heat Islands.

Obstacles and Adaptation in Urban Greening

The city’s transformation came with multiple challenges and setbacks. The survival rate of trees is lower than ideal, between 40% and 50%, due to factors related to air pollution, vandalism, and more. Because of the disparity between parts of the city, there was a clear difference in maintenance efforts between central zones and marginalized neighborhoods.

The greatest challenge for Mexico’s Urban Forestry Programme was the funding of the maintenance of green areas. However, this obstacle was taken care of by creating sustainable sources of funding, like those generated from park concessions and advertising. Another example is the dependence on groundwater for these initiatives, resulting in aquifer depletion, ground subsidence, and the implementation of water conservation measures. Due to the imbalance between green spaces and development in Mexico City, around 3.7% of green spaces are lost every year. This called for a need to collaborate with developers to come to a middle ground.

Conclusion

As urban populations face increasing pressure to address air pollution and enhance air quality, along with rising temperatures and ecosystem degradation.

With over 2,300 parks and green spaces adding up to 15% of the city’s total area, Mexico City has risen from being once labelled as “the world’s most polluted city.” Today, the city is looked at with admiration and sets an example for other metropolitan cities.

By combining decentralized municipal governance, public education, data-driven planting, and citizen-led activities, the city developed a framework model that can be used as a blueprint by global cities like Jakarta, Delhi, Lagos, or São Paulo.

Despite obstacles, Mexico City’s case study reveals that with the correct tools and collaboration, the future of urban cities can change for the better. Urban forestry needs to be seen as designing for social equity, sociological balance, and public health.

Pioneering air quality interventions and establishing biodiversity corridors, Reforma truly demonstrates how a city can transform from zero to one, turning an emergency into an example.

References

-

- Ballinas, M., & Barradas, V. L. (2016). Urban vegetation: Their contribution to the thermal comfort and climate change mitigation. Journal of Environmental Quality, 45(1), 157–166. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2015.01.0056

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (n.d.). Urban forestry in Mexico City. https://www.fao.org/4/u9300e/u9300e06.htm

- Hrehovcik, G. (2019, February 14). CDMX: Chapultepec and Paseo de la Reforma. WalkClickMake. https://walkclickmake.com/2019/02/14/cdmx-chapultepec-and-paseo-de-la-reforma/

- Mexico Historico. (n.d.). How Mexico City is leading the way in urban green initiatives. https://www.mexicohistorico.com/paginas/How-Mexico-City-is-Leading-the-Way-in-Urban-Green-Initiatives.html

- Mexico News Daily. (2023, March 2). Paseo de la Reforma: 10 facts about CDMX’s grand avenue. https://mexiconewsdaily.com/lifestyle/paseo-de-la-reforma-10-facts/

- Mexperience. (n.d.). Paseo de la Reforma. https://www.mexperience.com/paseo-de-la-reforma/

- Nieto de Pascual, M. (1988). Urban forestry in Mexico City: A case study. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved from https://www.fao.org/4/u9300e/u9300e06.htm

- Nowak, D. J., & Dwyer, J. F. (1992). Understanding the benefits and costs of urban forest ecosystems. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry, 18(1), 33–38. https://auf.isa-arbor.com/content/18/1/33

- Paris Peace Forum. (2023). Chapultepec Forest Environmental Transcendence. https://parispeaceforum.org/projects/chapultepec-forest-environmental-transcendence/

Shubhangi Sharma

About the author

Curious emerging researcher with a focus on sustainable development, spatial justice, and the everyday life of cities. With a background in architecture, Shubhangi Sharma’s work is grounded in real-world challenges and driven by a belief that design can and should do more.

Related articles

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “