How Multimodal Transport and TOD Are Shaping Global City Connections?

Multimodal transport and transit-oriented development (TOD) have emerged as essential strategies for linking global cities, stimulating economic growth, and addressing the complex challenges of urbanization. Multimodal transport integrates different modes of travel such as rail, buses, cycling, and walking into a unified, efficient system, while TOD promotes compact, walkable communities centered around high-quality transit. Together, these approaches have matured from localized planning tools into strategic mechanisms for regional and transnational integration. This essay traces their evolution, drawing on case studies from China, India, and Europe, to examine how these models are reshaping urban form and function, and to assess their potential in building more equitable and sustainable urban futures.

From Streets to Networks

The idea of multimodal transport has grown from simply designing roads that are safe for pedestrians, cyclists, public transit users, and drivers, into a more complex approach to managing how people move across cities and regions. First introduced in the early 2000s as a response to suburban sprawl and heavy reliance on private cars, multimodal planning now supports corridors that handle millions of daily trips across urban boundaries.

At the same time, transit-oriented development (TOD) has developed beyond increasing density around train stations. It is now used as a broader strategy to bring housing, businesses, and public spaces closer together, ideally within a five- to ten-minute walk of major transit lines.

Cities like Seoul, London, and São Paulo now use TOD not just to cut emissions or reduce traffic, but to shift economic focus toward neglected areas and connect separate municipalities into unified networks. In this updated approach, streets are no longer isolated paths but part of a larger system where trains, buses, trams, bicycles, and pedestrians work together to create more resilient and equitable urban fabrics.

Nodes, Corridors, Megaregions

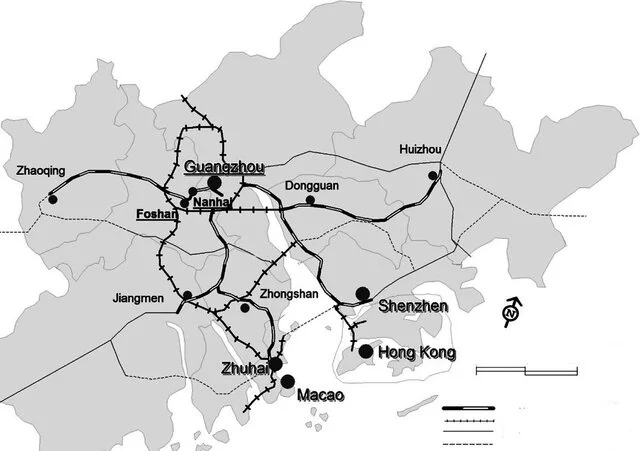

Cities act as nodes with corridors functioning as the arteries that link them. “Connectivity nodes” like ports, airports, and rail terminals, once centered on maritime trade, now also include freight trains and high-speed rail lines. In the Pearl River Delta, for instance, a planned 1,890 km rail network is set to connect Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong into a single urban system by 2030. At the same time, “economic nodes” have emerged around these transport hubs, where industries, services, and research centers cluster to benefit from being close together.

As corridors expand and intersect, they form multi-city areas called megaregions whose daily life is coordinated by shared transportation networks. The Delhi National Capital Region uses the Regional Rapid Transit System to link outlying suburbs with the city center. Similarly, Germany’s Rhine-Ruhr region connects its population of ten million through cross-border light rail systems. These megaregions are not just larger cities, but dynamic networks of people, goods, and capital moving through corridors managed by multiple authorities. Here, planners assess success not by how individual cities grow, but by how well the whole system performs in terms of speed, accessibility, and resilience to economic change.

Source: Website Link

Case Study - China’s High-Speed Metropolis

China’s high-speed rail network has reshaped the country’s urban landscape into a web of “station-cities,” where faster travel compresses distance and reorders economic relationships. By September 2022, the network had surpassed 410,000 km, more than the rest of the world combined, demonstrating a phenomenon known as “space-time convergence.” Major cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou now operate as interconnected cores, while mid-sized cities such as Wuhan and Suzhou are emerging as new centers of growth.

Wuhan’s plan to expand from four to eight passenger stations, each serving a specific role, shows how rail hubs are being intentionally developed as mixed-use economic centers, not just transit points. Suzhou North Railway Station anchors a new urban district that blends compact housing, office spaces, and riverside parks, integrating modern development with the city’s historic character.

However, this level of connectivity also has downsides. It creates a siphon effect, drawing investment and talent toward the best-connected cities and further concentrating growth in eastern China, often at the cost of inland regions. To address this imbalance, policymakers must improve land-use planning and apply true transit-oriented development (TOD) principles to prevent unchecked urban sprawl.

Case Study - India’s Polycentric Promise & Peril

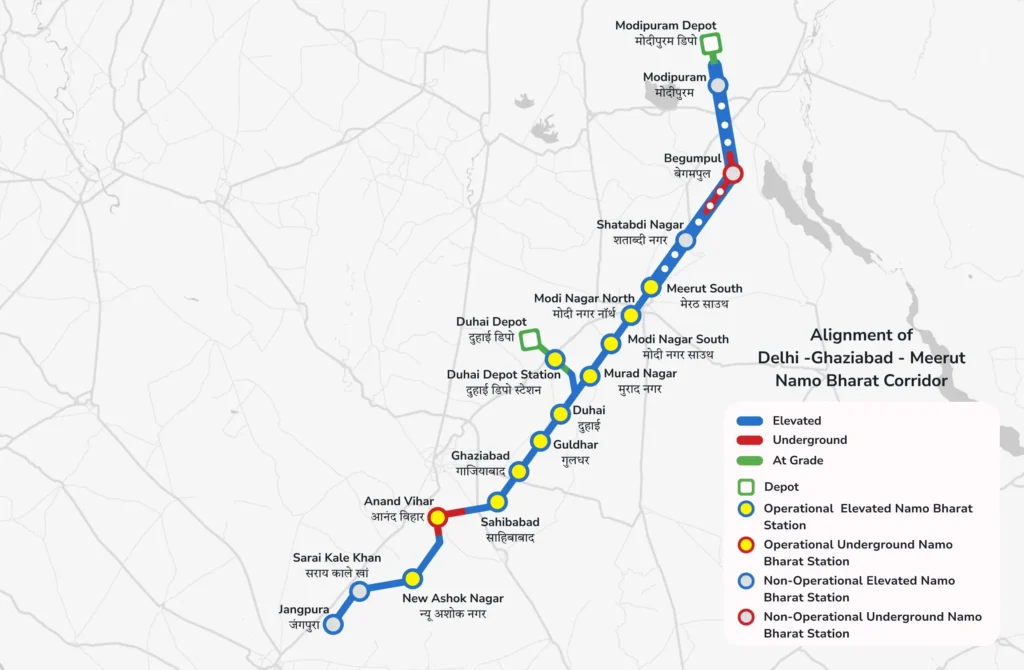

India’s National Capital Region (NCR) illustrates both the opportunities and challenges of polycentric planning. Created to spread urban functions across neighboring districts in Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and Rajasthan, the NCR depends on the Regional Rapid Transit System (RRTS) to connect this vast area. The Delhi–Ghaziabad–Meerut corridor alone serves ten million passengers each year, providing a fast, competitive 40-minute journey compared to three hours by road.

However, in cities like Meerut and Ghaziabad, land prices near RRTS stations have risen by as much as 67 percent since late 2023, driving speculative development and threatening the affordability of long-standing communities. While the NCR Planning Board offers an institutional structure, actual decision-making is divided among multiple state governments and municipal bodies, causing delays in sub-regional planning and conservation efforts. Without a unified authority, the enforcement of transit-oriented development (TOD) varies widely with some areas having well-integrated bus terminals and mixed-use zones, while others lag behind. As a result, physical connectivity has advanced faster than policies on affordable housing and value capture, placing low-income residents at risk of displacement.

Case Study - Europe’s Transnational Vision

Europe’s Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) represents a continent-wide effort to connect national transport systems into a unified mobility framework. Established by regulation, nine core corridors and two horizontal priorities link ports, airports, and urban centers which includes 431 cities required to implement Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans, ensuring that rail, road, inland waterways, and maritime routes operate as an integrated system. The “Next-Gen TOD” approach broadens this focus from individual stations to entire corridors, aiming for balanced economic, social, and environmental benefits.

Despite significant infrastructure investments, cross-border interoperability remains a challenge. For example, the Amsterdam–Brussels–Paris route cut travel times by forty-five minutes through the EuroCity Direct service, but capacity improvements have stalled and ticket prices remain above €100. These issues stem from differing train-control systems, licensing, and fare policies. Likewise, planned upgrades under the Connecting Europe Facility have faced delays as Member States work through complex approval procedures and competing national interests..

Airport Cities, BRI, and Global Integration

In emerging economies, airports and transnational corridors play a major role in shaping urban development. Addis Ababa’s planned Abusera airport city, designed to handle 110 million passengers annually and featuring hotels, logistics parks, and housing, illustrates a move toward airport-led transit-oriented development (TOD) as a driver of regional growth. Similarly, Bangkok’s Don Mueang expansion repurposes underused land to create mixed-use areas that combine mass transit, commercial centers, and residences.

At the same time, China’s Belt & Road Initiative has supported major rail and port projects across Africa and Southeast Asia. Examples include the Addis Ababa–Djibouti Railway, which cut freight costs in half and sped up trade; Kenya’s Mombasa–Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway, which increased passenger and cargo traffic; and the Jakarta–Bandung high-speed rail line, which shortened travel times and encouraged corridor development.

However, these developments also bring challenges. Land values near airports often double quickly, leading to speculative bubbles, while around 15 million people worldwide were displaced by infrastructure projects in 2019 alone. Environmentally, large logistics zones and new terminals can disrupt habitats, change water systems, and strain resources. Additionally, Belt & Road investments raise geopolitical concerns, including debt dependence and uneven power relations.

Economic Benefits of Multimodal Transport and TOD

Multimodal transport and transit-oriented development (TOD) projects not only improve connectivity but also drive strong economic growth. One of the most immediate impacts is job creation. During construction, large projects like China’s high-speed rail network and India’s Regional Rapid Transit System (RRTS) generate thousands of jobs in engineering, building, and related fields. Once operational, they provide ongoing employment for maintenance, operations, and customer service, supporting long-term economic stability.

Beyond jobs, these systems boost productivity by cutting travel times. For example, China’s high-speed rail has significantly contributed to the country’s GDP by enabling faster movement of people and goods, improving business efficiency and output. Similarly, India’s RRTS is expected to enhance trade and commerce between cities, promoting regional economic integration.

Improved transport links also attract investment, as companies prefer locations with efficient connectivity. This often raises property values near transit hubs, increasing tax revenues for local governments. However, rising property prices must be managed carefully to avoid speculative bubbles and keep housing affordable.Overall, these projects act as catalysts for economic development, creating a ripple effect that benefits multiple sectors and enhances the quality of life for citizens.

The Role of Technology

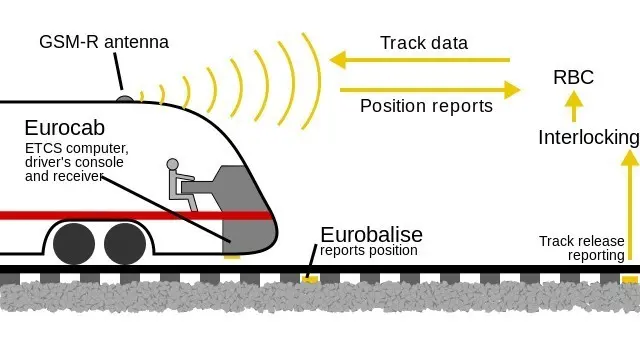

Technological innovation is essential for improving the efficiency, safety, and sustainability of multimodal transport and transit-oriented development (TOD) projects. Advanced signaling systems, such as the European Rail Traffic Management System (ERTMS), enable real-time train control, which enhances safety, reduces delays, and allows more trains to run on the same tracks, boosting capacity without major infrastructure upgrades. Energy-efficient train models, like Japan’s Shinkansen, lower operational costs and reduce carbon emissions by using less energy.

Digital tools such as mobile apps, smart cards, and real-time passenger information systems also improve the travel experience by making journey planning and payments easier, encouraging more people to use public transport. Technology can further address broader goals such as environmental sustainability and social inclusion. For example, data analytics can help reduce emissions by optimizing energy use, while smart city technologies can make transport more accessible to marginalized groups.

As these technologies advance, they will strengthen transport networks, making them more resilient, inclusive, and adaptable. However, careful implementation is necessary to avoid exacerbating digital divides or displacing workers through automation.

Conclusion

Multimodal transport and transit-oriented development (TOD) have evolved from local urban design tools into powerful strategies for integrating city-regions across the globe. Whether through Complete Streets, China’s 410,000 km high-speed rail network, Delhi’s polycentric RRTS, Europe’s cross-border TEN-T corridors, or airport-led TOD in cities like Addis Ababa and Bangkok, these initiatives reshape economic landscapes, expand access to opportunity, and redefine regional scale.

However, their true success is not measured by infrastructure alone, but by the equity and resilience they promote. Unchecked land-value spikes, displacement of vulnerable populations, fragmented governance, and environmental harm highlight the risks of infrastructure-driven growth without strong social and ecological safeguards.

A “Next-Gen” approach requires integrated governance across jurisdictions, effective land-value capture strategies, enforceable affordable housing policies, and comprehensive environmental review processes. By aligning speed with justice, and efficiency with care, cities can turn transport corridors and nodes into inclusive engines of shared prosperity.

In this synthesis, connectivity becomes more than a technical achievement. It becomes a commitment to building urban fabrics where every citizen benefits, ecosystems thrive, and regional networks endure as equitable, sustainable foundations for the twenty-first century.

References

- Carlton, I. (2009). Histories of transit-oriented development: Perspectives on the development of the TOD concept. UC Berkeley: Institute of Urban and Regional Development. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7wm9t8r6

- City of New York, Department of Transportation, Ministry of Environment of México, Prasanna Desai Architects, DOG97209 (flickr), & Institute for Transportation and Development Policy. (2017). TOD Standard (3rd ed.). ITDP. https://www.itdp.org

- How Addis Ababa is on the frontier of sustainable transport for African cities | Smart Cities Dive. (n.d.). https://www.smartcitiesdive.com/ex/sustainablecitiescollective/friday-fun-addis-ababa-frontier-sustainable-transport-african-cities/1046471/#

- Mittal, D. (2025, June 23). RRTS boosts land prices in Meerut, Ghaziabad; 30% to 67% growth witnessed since October 2023. The Indian Express. https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/delhi/rrts-boosts-land-prices-in-meerut-ghaziabad-30-to-67-growth-witnessed-since-october-2023-10082163/

- Tam, A. (2024, February 13). Fostering sustainable, accessible African cities through TOD. Institute for Transportation and Development Policy. https://itdp.org/2024/02/13/fostering-sustainable-accessible-african-cities-through-tod/

- Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T). (n.d.). Mobility and Transport. https://transport.ec.europa.eu/transport-themes/infrastructure-and-investment/trans-european-transport-network-ten-t_en

- Urban Health Repository. (n.d.). https://urbanhealth-repository.who.int/

Zou, S., Fan, X., Wang, L., Zhang, L., & Chen, Y. (2024). High-speed rail new towns and their impacts on urban sustainable development, 11, 894. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03337-2

Pragya Upadhaya

About the author

Pragya is an architect from Nepal with a keen interest in urban planning, mobility, and public life. Her work examines how cities function at street level and how design can meet the social and spatial needs of residents, especially in rapidly growing urban centers in the Global South.

Related articles

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “