Innovative Parks and Plazas Shaping the Future of Public Life

Urban public spaces have changed dramatically in the 21st century. What was once conceived as nothing more than passive greenery or ornament in urban design is now recognized as indispensable platforms of promoting social interaction, cultural exchanges, environmental sustainability, and urban creativity. As cities become more densely populated, diverse and complex, the demand for inclusive, multi-functional, and flexible public spaces is becoming even more pressing.

New parks and plazas in the contemporary era are being envisioned as hybrids of landscape architecture, interactive technology, and public art–surfaces that fuse in the ecologies of both environment and experience. They offer variety for residents and visitors, help mental and physical health, and add to the resilience of cities to climate change. In most of the cases, they also contribute to reanimating industrial zones, to social inclusion and to sustainable development.

Using three cross-national vignettes of the High Line in New York, Superkilen in Copenhagen, and Zaryadye Park in Moscow it discusses trends that resonate with these challenges. All of these projects provide singular perspectives on what public design can mean for cities, for peoples, for the challenges and opportunities of urban life in the future.

What Makes Park and Plazas Innovative?

Innovative parks, in the general sense, are a significant urban public space innovation. They are different from the traditional parks, whose key advantage is recreational, because these new-type park spaces are developed on the principles of flexibility, multiformity, and responsiveness to social needs. They integrate natural systems with human conduct and frequently result from the renovation of old industrial areas or vacant city spaces.

Rosa and Lindner (2017) observe that such parks “reinvent infrastructure as public space,” enabling experiential user encounters that redefine the relationship of people to the city. Repurposing abandoned train tracks, factories, or vacant lots into green corridors and community centers is an excellent instance of design-driven urban land-use innovation. One distinguishing feature of innovative parks is that they prioritize inclusivity, participatory practices, and sustainability. These parks are not merely limited to form or recreational uses; they also function as spaces for civic activities, environmental learning, and cultural display. Synthesizing landscape architecture with technology and public art works, innovative parks are created to reflect the identities of the places as well as greater urban challenges. Collectively, these parks are an exemplar of public space—where design, environmental systems, and civic activity converge to create robust, positive urban spaces.

Case Study1 : The High Line – New York

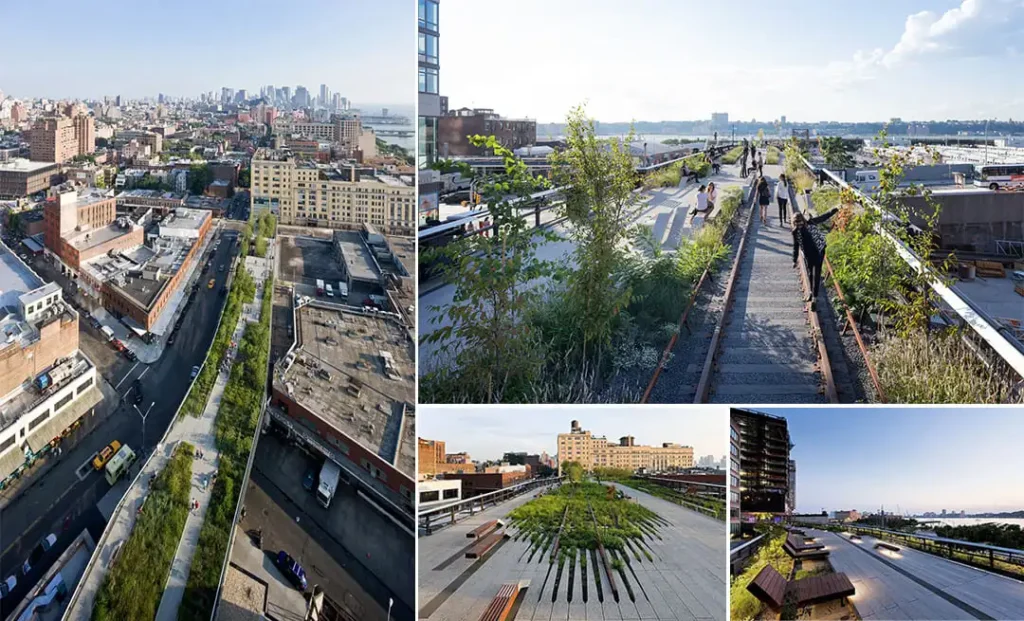

New York City’s High Line is the celebrated instance of urban infrastructure adaptive reuse, refunctioning an obsolete elevated railway into a 2.3-kilometer linear public park. The project was opened in 2009 and is much-cited in the debate surrounding landscape urbanism; it has been described as one of urban design’s greatest successes. Adrian Benepe described it as “more than just a park – it’s a work of art.” High Line has succeeded in drawing millions of tourists annually and propelling noticeable increases in neighborhood property values.

Though widely praised, the High Line contributed to gentrification, raising nearby property values and displacing low-income residents. Its co-founder later admitted to insufficient early community engagement .

Subsequent Friends of the High Line initiatives included the enforcement of local hire practices, educational programs, and community events. These interventions occurred subsequent to development and did not benefit marginalized groups who were already negatively impacted by displacement.

The High Line is now regarded as an international benchmark in public space design, illustrating the promise and risks of design-driven urban transformation. It is admired as innovative and stunning but to caution against the risks of design over community-led, collaborative planning.

Source: Website Link

Case Study2 : Superkilen – Copenhagen

The project reflects the tension between visual diversity celebration and real social inclusion, making it a key urban design case.

Superkilen, located in Copenhagen’s Nørrebro district, is a prominent example of contemporary urban design focusing on multicultural representation. The park stretches about 750 meters and is divided into three zones: Red Square (urban activities and sports), Black Market (social interaction), and Green Park (recreation and green space).

What distinguishes Superkilen is its incorporation of over 100 urban features from more than 60 countries. These range from Moroccan fountains and Brazilian benches to Japanese playground equipment, each with bilingual signage in Danish and the country of origin. The selection process involved community participation to ensure contextual relevance and foster ownership among residents.

Critical response has been mixed. ArchDaily (2012) called the project a “surreal collection of global urban diversity,” praising its visual impact. Schwarz (2022) criticized its superficiality, questioning cultural interpretation depth and community engagement.

Technically, Superkilen uses eco-friendly rainwater management systems collecting about 55% of precipitation to water plants and support sustainable urban living. It has won awards like the AIA Honor Award (2013), the Aga Khan Award (2016), and a Designs of the Year nomination (2013).

Case Study3 : Zaryadye Park– Moscow

Zaryadye Park, opened in 2017 near the Kremlin, is a landmark in contemporary landscape architecture. Designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro in partnership with Russian firms, it sits on the former site of the Rossiya Hotel and aims to merge architecture and landscape into one unified public space.

A defining feature of the park is its recreation of four Russian biomes—tundra, steppe, forest, and wetlands—offering a multisensory experience that blends education, ecology, and culture. Notable attractions include an artificial ice cave, a glass-structured media center, and a “floating” bridge over the Moskva River, all of which express national identity through design.

Despite praise for innovation, the park has faced criticism over its $480 million cost, especially given Moscow’s broader urban needs. However, it incorporates sustainable features like automated climate control and year-round programming to enhance public utility.

Architect Charles Renfro described Zaryadye as “a place where architecture and landscape are one,” reflecting its ambition to redefine urban public space through immersive and ecologically responsive design.

Design vs. Inclusion: The Real Test of Urban Park Innovation

Let’s not sugarcoat it—urban redevelopment projects, no matter how innovative, run into some serious obstacles. The High Line in New York? It’s been celebrated by designers, but the reality underneath is a bit rough. The project’s been linked to rapid gentrification and the displacement of longtime residents—so, while it’s a visual asset, the social consequences are complicated (Bliss, 2017; Rosa & Lindner, 2017).

Superkilen in Copenhagen is another case. Sure, it’s praised for showcasing multiculturalism, but critics argue it falls short of real inclusion. Basically, it displays cultural objects without meaningful engagement or integration, which kind of turns diversity into a surface-level spectacle (Schwarz, 2022).

Zaryadye Park in Moscow? That’s a whole other challenge. The park is architecturally ambitious, and the ecological features are impressive, but the financial burden is significant. Both construction and long-term maintenance strain city budgets.

When you look at all three, there’s a clear pattern: cities are struggling to reconcile the desire for iconic, visually striking spaces with the need for true social equity and sustainable operations. If that balance isn’t addressed, these parks risk becoming mere aesthetic symbols rather than catalysts for inclusive community development.

From Challenges to Inclusive Urban Solutions

Addressing the persistent challenges in urban redevelopment boils down to a few critical practices. First, authentic community engagement isn’t optional—it’s foundational. This means interfacing directly with residents, especially those typically marginalized. Communication must be clear: workshops, multilingual surveys, and interactive tools help ensure feedback is truly representative. Urban design should be grounded in citizens’ daily lives. Prioritize safe public spaces, encourage interaction, and shape design decisions through stakeholder input—not from consultants with one-size-fits-all solutions.

Aesthetics matter, but they aren’t everything. Projects must deliver both architectural quality and daily usability—spaces that serve as landmarks and promote equity and sustainability. This can happen only through participatory planning with all involved. Financial sustainability is essential. Complete upkeep plans and diverse financing—public or private—are key to avoiding cost pressures that undermine a project’s future. Together, these strategies support the creation of urban spaces that are not only visually appealing, but also inclusive, durable, and capable of sustaining vibrant communities.

Digital Innovation in Parks and Plazas

Modern parks are no longer just spaces of nature and leisure—they are becoming technologically enhanced platforms for public life. Through smart infrastructure and interactive design, innovative parks like Zaryadye, Bishan Park, and Hudson Yards redefine how people gather, learn, and engage.

Zaryadye Park in Moscow blends immersive storytelling with ecological education. Singapore’s Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park combines landscape design with real-time flood monitoring, improving resilience and public safety. In New York, Hudson Yards’ digital twin system enables responsive urban planning based on real-time data.

Technologies such as AI and AR are also expanding inclusivity and user experience. For example, in Seoul’s Digital Media City, AR apps allow users to explore layered cultural content in real time.

As the Gehl Institute (2022) stresses, however, technology should enhance—not replace—human interaction. The future of public life lies in spaces where innovation fosters community, equity, and connection—not just spectacle.

Conclusion

High Line, Superkilen, and Zaryadye Park—these aren’t just ornamental green spaces; they stand as dynamic case studies in the evolution of urban public infrastructure. Their designs operate at the intersection of architecture, cultural programming, and ecological integration, fundamentally reshaping how dense cities accommodate communal life. Yet, even the most avant-garde aesthetics cannot compensate for shortcomings in equity and inclusivity.

For any public space to function meaningfully within its urban context, it must be anchored in principles of accessibility, social justice, and community co-creation. Designing for people is no longer enough—designing with them is essential. Authentic engagement must occur not only during consultation but throughout the lifecycle of the project.

To guide future practice, it is recommended that urban designers adopt a participatory framework backed by long-term stewardship models, where local communities are not just users but stewards of their environment. By integrating emerging technologies with grassroots input, public spaces can evolve into adaptive systems that reflect local identity, foster belonging, and build urban resilience.

Only then can urban design truly serve as a democratic tool for shaping the future of public life.

References

- Rosa, B., & Lindner, C. (2017). Deconstructing the High Line: Postindustrial Urbanism and the Rise of the Elevated Park. Rutgers University Press.

- Bliss, L. (2017). The High Line’s next balancing act. CityLab. https://www.citylab.com/design/2017/02/the-high-lines-next-balancing-act/515391/

- ArchDaily. (2012). Superkilen / Topotek 1 + BIG Architects + Superflex. https://www.archdaily.com/286223/superkilen-topotek-1-big-architects-superflex

- Gintoff, V. (2016). Charles Renfro Discusses DS+R’s Winning Proposal for Zaryadye Park in Moscow. ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily.com/785913/charles-renfro-discusses-ds-plus-rs-winning-proposal-for-zaryadye-park-in-moscow

- Schwarz, M. (2022). Atmospheres of designed diversity? In Entangled Histories of Art and Migration (pp. 142–151). De Gruyter.

- ResearchGate. (2017). Imbricated Spaces: The High Line, Urban Parks, and the Cultural Meaning of City and Nature. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312106545

- UN-Habitat. (2023). Unlocking the Potential of Cities: Financing Sustainable Urban Development. https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2023/11/unlocking_the_potential_of_cities_-_financing_sustainable_urban_development_-_06-min.pdf

- MDPI. (2023). Urban Parks and Smart Technologies. Sustainability, 15(3), 1957. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/15/3/1957

- ScienceDirect. (2022). Smart urban spaces and digital tools for inclusive public life. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1618866722000292?via%3Dihub

- Assmann, J. (n.d.). Superkilen, Copenhagen. https://www.jensassmann.com/superkilen/?utm_source

Salma Shafei Mohamed

About the author

Salma Shafei Mohamed, an architecture student interested in integrating her academic studies with contemporary issues in design and planning, aiming to deepen her understanding of architecture’s role in enhancing quality of life in communities.

Related articles

10 Inspiring Interactive Public Space Designs Worldwide

Top 10 global case studies in Urban Conservation Projects

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “