Kenzo Tange – Japan’s Metabolist & Modernist Urban Vision

Kenzo Tange was an innovative architect who successfully bridged the gap between traditional Japanese aesthetics and modernist innovation, and played a significant role in developing Japan’s cities after the war. His projects, including the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park and Yoyogi National Gymnasium, reflected his flexible, people-focused design approach. Tange, as a leader of the Metabolist movement, redefined the nature of the connections between architecture, society, and the changing city.

Kenzo Tange's Biography

Kenzo Tange was born in 1913 in Osaka, where he showed an interest in architecture at a very early age. He grew up in highly turbulent times in Japan during and after World War II. After graduating from the University of Tokyo, Tange started to be recognized for his unique modernist style for combining traditional features with modernist structures. Designs made by him in his early periods were not just visually appealing but also technically advanced. The events of the war deeply influenced Tange so much that he wanted to develop a place that conveys healing and contemplation.

His breakthrough was with Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, which was a memorial to the devastating effects of nuclear war and a memorial to a peaceful future. During the course of the 1960s and later, Tange was associated with the Metabolist movement, which preached architecture that adapted to the city. His large catalogue of extensive work in many parts of the world made him a leading personality in international architecture. Tange once said, “Architecture is a tool for shaping the environment and making it effective for human interaction.” This quote summarizes his work as an architect interested in human-environment interaction.

Architectural Philosophy

The philosophy behind the works of architect Kenzo Tange was based on the humanity in built architecture and the role of heritage, which the architect was keen on maintaining. His creations are a blend of modernism and Japanese traditional arts, where he focused more on harmony between structure and nature. Tange scientifically examined cityscapes and advocated lively buildings that respond to the variable needs of the consumers. He believed architecture should foster a sense of community and belonging, and because of this, he started to place public spaces in his projects. These concepts were directly connected to his contribution to the development of the Metabolist movement, a progressive style of thinking that considered cities as an art form that needed to be managed as a living, breathing organism.

Source: Website Link

The Metabolist Movement

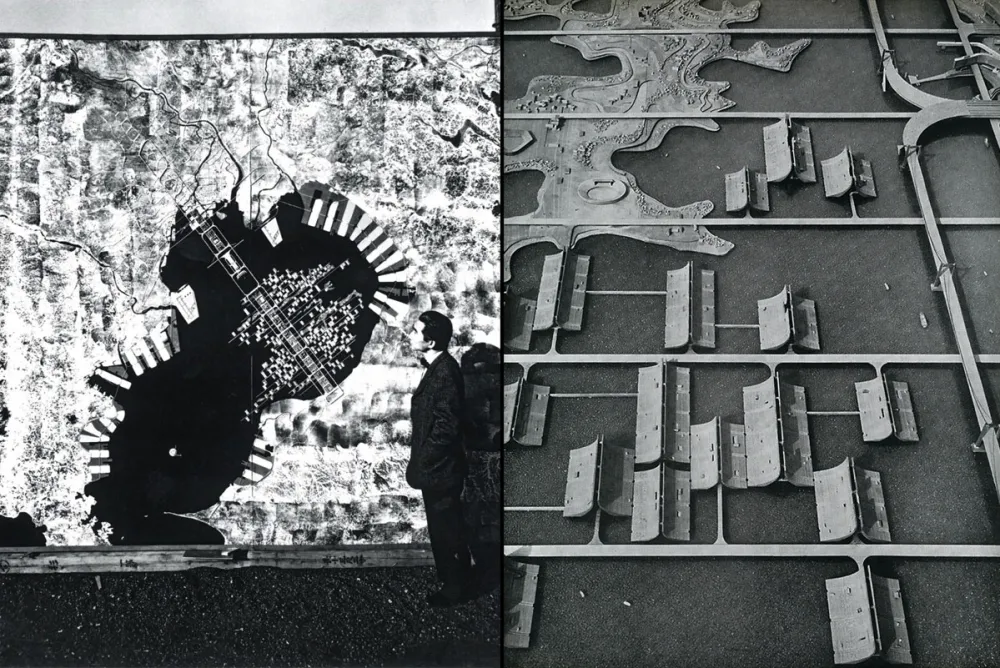

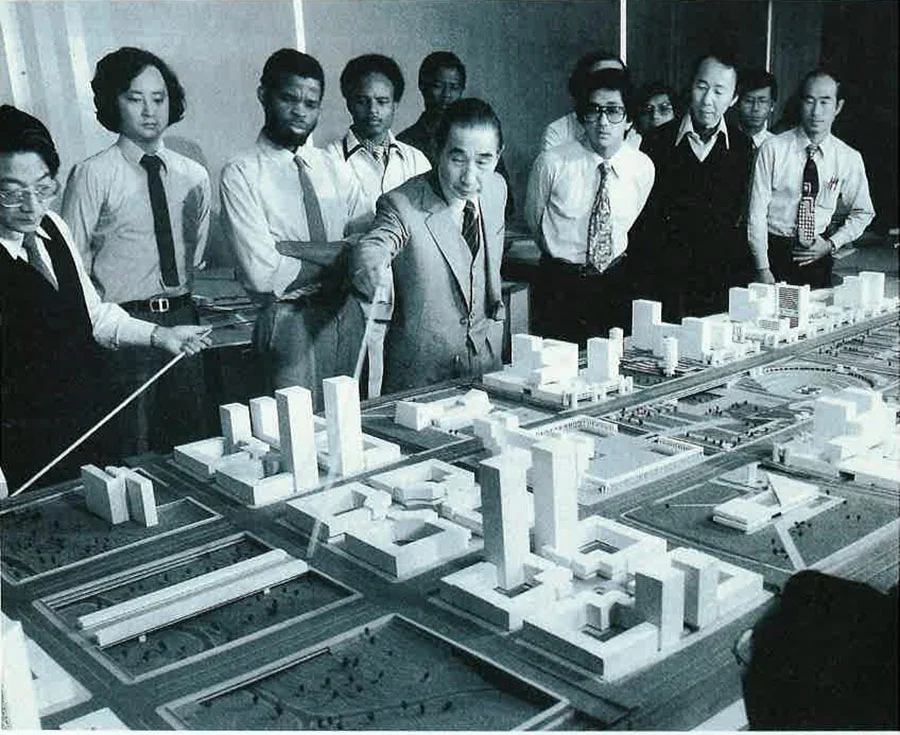

Kenzo Tange co-founded the Metabolist movement in post-war Japan due to the necessity of rapid urbanization and the needs that society had at that time. This style of architecture attempted to design dynamic, versatile buildings that could change and develop through the years. Tange also believed in using the pattern of organic growth in urban planning.

A great example of this idea is “A plan for Tokyo 1960”. It suggested building a huge structure made up of sections that could grow or shrink based on the situation to fit the city’s large landscape. The Plan for Tokyo was never implemented, but it sparked Tange’s following architectural and urbanism initiatives, including the 1964 Summer Olympics’ Yoyogi National Gymnasium. Another thing Tange talked about a lot was how important it was for a building to talk to its surroundings. “In architecture, we have the power to change the world one building at a time,” he said. He was in charge of the Metabolist movement, which led to discussions about how towns change and how this environment affects people. This trend is still relevant to date, which shows that buildings should adapt to the changing city surroundings.

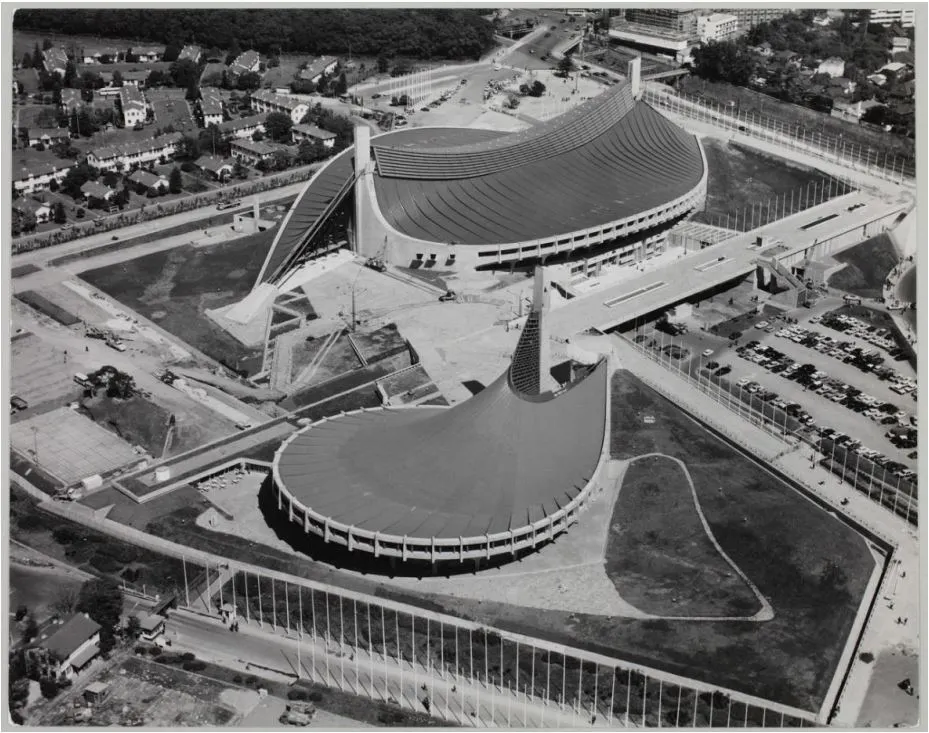

Notable Project 1: Yoyogi National Gymnasium

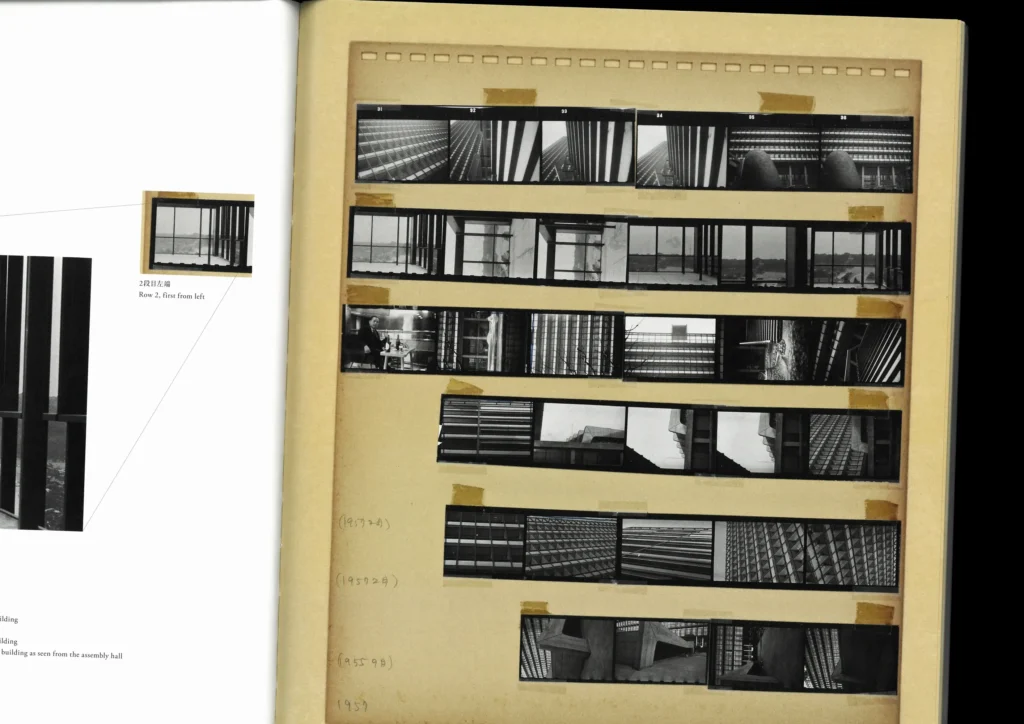

The Yoyogi National Gymnasium is among Kenzo Tange’s most iconic modern architectural works. It represents a powerful fusion of aesthetic innovation and technical engineering. This building was designed to host the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, and with a unique suspended roof design, a trademark of Tange’s ingenuity. The gymnasium is a perfect example of modernism, and it is a tribute to ancient Japanese architecture since it has graceful, flowing lines.

This building features a high level of knowledge Tange possessed in the engineering field and is used as a contemporary representation of Japan out of its burnt-down ruins and into the world limelight. Unification of practical demands with the artistic point of view permitted Yoyogi National Gymnasium to communicate with its environment and people. The innovative use of cantilevered roofs by Tange has been the model for many other architects, thus making the gymnasium one of the most prominent structures of modern architecture. The structure remains a place of major occurrences and a perpetual font of inspiration and modernity for the generations to come.

Notable Project 2: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park serves as a profound memorial to the victims of the atomic bomb. Devised by Tange, finished in 1954, it blends remembrance with a vision for healing and renewal, transforming a site of devastation into a symbol of peace. The park also has several Significant structures, among which one can find the famous Atomic Bomb Dome that serves as a solemn message about how terrible nuclear war could be.

Tange managed to intelligently combine modernist ideas and deep belief in the history of culture to make a space that tries to make a person reflect, grieve, and dream about peace. His design philosophy is paralleled in his self-statement, “We have to develop an area that will remind of the individuals who died.” The detailed design and use of water in the layout not only serves a decorative purpose; it also represents purification and healing. It has become a sign of peace and receives millions of people every year, and is now a place where memorials and educational activities are commemorated, which gives it international significance and value.

Achievements

Kenzo Tange’s influence in architecture is vast, marked by prestigious awards and groundbreaking works that combined tradition with modernism. His achievements include:

- Winner of the 1987 Pritzker Architecture Prize, often called the “Nobel Prize of Architecture,” recognizing his innovative blend of traditional Japanese and modern design

- Other Awards and Honors: Royal Gold Medal (1965), AIA Gold Medal (1966), and Praemium Imperiale (1993), acknowledging his global impact.

- Iconic Projects: Designed the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, symbolizing peace and recovery, and the Yoyogi National Gymnasium with its revolutionary suspended roof for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.

- Urban Planning Innovation: His “Plan for Tokyo 1960” introduced adaptable urban growth concepts, inspiring the Metabolist movement.

- Mentorship and Teaching: Guided prominent architects like Arata Isozaki and Kisho Kurokawa and established Tange Associates, a lasting architectural practice.

Impact and legacy

Kenzo Tange’s impact on architecture and urban design goes beyond his actual works, as he helped shape the modern thinking and practice of architecture. His work was able to merge the older tradition of life with modernity, which offers cultural identity in a dynamic and fast city. His support of the Metabolist movement emphasized the need for flexible urban spaces, which applies more frequently nowadays in the debate regarding sustainable development and urban renewal.

Tange’s buildings remind us of architecture’s role in promoting peace and community. His global influence is evident in educational institutions, lasting design principles, and numerous international accolades. His claim that architecture should be an expression of the conditions of time and culture is very convincing to the architects who endeavour to establish meaningful spaces. Finally, Tange’s vision on architecture remains a current topic of discussion on how the built environment can contribute to the development of a community.

The legacy of Tange demonstrates the union between tradition and innovation that architecture implies. His synthesis between Japanese aesthetics and modernism influenced the architecture after the war and the architecture of world cities. His work was not merely a visual but a developer of connections and a healing product with a social and philosophical purpose. There are still projects that bear the emotional density and technical brilliance, e.g, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park and Yoyogi National Gymnasium. Although powerful, the Metabolist vision was by no means immune to criticism. Other ambitious plans of Tange as a large-scale urban proposal, were regarded as potentially utopian or technically impossible, such as in the plan by Tange titled: A Plan for Tokyo 1960. With time, the idea of megastructures touted by the movement was difficult to implement, which demonstrated the disconnection between theory in the abstract and practical flexibility. Nevertheless, it is his argument on flexible and anthropocentric design that is applicable in a debate on green and robust urbanism. Kenzo Tange did not only design buildings, but also systems, communities, and memory.

References

Luna, M. A., et al. (2022). Between war and peace, past and future: Experiencing the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. Integrative Psychological and Behavioural Science, 56(3), 453–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-022-09723-2

Maki, K., & Niihata, Y. (2018). The landscape design in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ), 83(751), 1117–1125. https://doi.org/10.3130/aija.83.1117

Maki, K., & Niihata, Y. (2020). Landscape design in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park: Transition of the design by Kenzo Tange. Japan Architectural Review, 3(2), 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1002/2475-8876.12136

Parkhomchuk, Y. (2023). Transformation of tradition in Kenzo Tange’s projects as a way of shaping contemporary Japanese architecture. Architectural Studies, 2, 96–109. https://doi.org/10.56318/as/2.2023.96

Toyokawa, Y. (2022). A comparison of the design processes of the Yoyogi National Gymnasium and the Kagawa Prefectural Gymnasium. Japan Architectural Review, 5(4), 412–422. https://doi.org/10.1002/2475-8876.12328

Lin, Q. (2020). Kenzo Tange. In Oxford Bibliographies in Architecture. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/obo/9780190922467-0049

Varsha Mokal

About the Author

Varsha Mokal, an architecture graduate from India with a Master’s in Urban Design from the UK, is passionate about harnessing GIS and AI to shape sustainable, inclusive cities. Specialising in spatial analysis and ecological design, she leverages data-driven strategies to create future-ready urban solutions. Skilled in digital tools and research, Varsha focuses on innovative approaches to energy planning, mobility, and community development. Committed to blending technology, design, and equity, she aims to drive forward-thinking urban projects that build a resilient and smart urban environment.

Related articles

Top 10 Most Livable Cities in the World

Anne Hidalgo – aris Transformation & Pedestrian Policy

Sector 17 Plaza, Chandigarh: Modernist Urbanism

UDL Illustrator

Masterclass

Visualizing Urban and Architecture Diagrams

Session Dates

23rd-24th August 2025

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “