Nature-based Solutions in Urban Planning

Relevance of nature-based solutions in an urbanized world

Cities face a myriad of social, economic, and environmental challenges that are expected to be exacerbated by increasing urbanization and the impacts of climate change. Over the past decades, the large-scale replacement of natural ecosystems with built up areas has put cities and their surroundings under increasing pressure in terms of resource scarcity, degraded air and water quality, reduced availability of green space, etc.

In addition, rising global temperatures have led to an increase in the frequency and intensity of natural disasters such as floods, droughts and heat waves leaving densely-populated areas, their citizens and critical infrastructure particularly vulnerable.

Nature-based solutions such as green roofs, floodplains, open green spaces, urban trees and bioretention swales constitute effective means of addressing these challenges. In addition, they safeguard urban biodiversity and increase the attractiveness and quality of life experienced in urban areas.

“Nature-based solutions are defined as actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore natural or modified ecosystems that address societal challenges effectively and adaptively, simultaneously providing human well-being and biodiversity benefits.” (International Union for Conservation of Nature, 2016).

“Ecosystem services are the benefits people obtain from ecosystems. These include provisioning services such as food, water, timber, and fiber; regulating

services that affect climate, floods, disease, wastes, and water quality; cultural services that provide recreational, aesthetic, and spiritual benefits; and supporting services such as soil formation, photosynthesis, and nutrient cycling.” (Ecosystem Millennium Assessment, 2005).

Green infrastructure “is a strategically planned network of natural and semi-natural areas with other environmental features designed and managed to deliver a wide range of ecosystem services. It incorporates green spaces and other physical features in terrestrial and marine areas. On land, green infrastructure is present in rural and urban settings. It can sometimes offer an alternative, or be complementary, to standard gray solutions.” (European Commission, 2010).

Ecosystem-based approaches to adaptation refer to “the use of biodiversity and ecosystem services to help people adapt to the adverse effects of climate change as part of an overall adaptation strategy.” (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2009).

The multi-functionality, value and cost-effectiveness of nature-based solutions

Nature-based solutions are also dubbed ‘no-regret’ solutions since they are multifaceted offering a plethora of co-benefits in addition to the purpose they are intended for. As the following examples show, these include social, environmental and economic benefits drawn from the diverse portfolio of ecosystem services that nature-based solutions provide:

- Green walls and roofs foster urban biodiversity and improve the attractiveness of an area in addition to lowering tenants’ cooling costs.

- Urban gardens increase local food sovereignty, enhance social cohesion, provide opportunities for learning and contribute to urban biodiversity.

- Forests and vegetation in and around urban areas sequester carbon, regulate the micro-climate, purify the air and reduce urban noise. In addition, spending time in nature and in direct contact with natural elements enhances mental health and well-being.

There are numerous ways to more specifically identify the direct and indirect contributions of nature-based solutions, such as the monetary valuation of ecosystem services. In China, for example, the air purification and temperature regulating services of Beijing’s forest ecosystems have been valued at 7.72 billion yuan (1.03 billion euro) annually based primarily on avoided air pollution charges and electricity savings (Wu et al., 2010).

Due to their multi-functionality, their value and their relatively low cost of implementation and maintenance, nature-based solutions constitute cost-effective approaches to urban challenges, either on their own or in combination with gray infrastructure solutions.

Nature-based Solutions for Sustainable Urban Development

Nature-based solutions are important for urban areas on three levels:

- Within cities, where they can provide natural shading and reduce urban heat island effects and cooling needs, manage run-off water, improve health and well-being by reducing air pollution, and offer recreational spaces;

- Around cities, where they can form part of city-region interlinkages related to watershed management, recreational spaces, wildfire management, reduction and capture of CO2, sand and dust storm reduction measures;

- Away from cities, where nature-based solutions can be applied to the procurement of goods and infrastructure as well as built environment decisions that influence urban supply chains.

Nature-based solutions can address urban challenges exacerbated by growing urban populations and the impacts of climate change. They are multi-functional, cost-effective and provide a wide range of benefits, from improving public health to reducing energy costs and pollution to regenerating urban spaces.

Local governments can use green roofs and green infrastructure to help cities become more resilient to extreme weather, support urban gardens to strengthen food sovereignty and increase green and blue spaces, improve quality of life for residents and create popular recreation areas.

Nature-based solutions can drastically change urban landscapes and provide diverse benefits both for city governments and for residents. Yet there is still work to be done to facilitate wider implementation. Further evidence on nature-based solutions is still needed to effectively advocate these approaches and leverage resources and finances for implementation. Local governments also have an important role to play in building collaboration among stakeholders to ensure nature-based solutions become part of planning and policy across sectors.

Nature-based solutions for urban regeneration

Availability of and access to urban green space are important indicators assessing the livability of urban areas. Local governments are increasingly turning to nature-based solutions to provide attractive settings and to enhance the quality of life, health and well-being of their residents. Examples include:

- The number of inner-city lanes is reduced to make space for greenways that improve air quality and encourage the use of alternative means of transportation.

- Polluted and degraded rivers and wetlands are restored to near-natural systems simultaneously increasing water quality and property values.

In addition, nature-based solutions are used to spur urban renewal processes through the regeneration of deprived and neglected residential and industrial areas. This becomes especially relevant for cities undergoing a post-industrial transition.

Examples include:

- Former factory sites and disused infrastructure are torn down and detoxified using bioremediation. In turn, they are transformed into public green spaces for recreation.

- Abandoned land is converted into community gardens and urban farms to enhance social cohesion and regenerate disadvantaged urban areas.

Examples of Nature-based Solutions

Examples of urban Nature-based Solutions include:

- Forested catchments that provide clean water and store carbon.

- Urban wetlands that increase water infiltration and reduce flood risks.

- Urban and peri-urban farms that reduce food miles and connect people to the food they eat.

- Parks, tree-lined streets, green roofs and building facades that mitigate the urban heat effect and accelerate water drainage while reducing noise pollution, air pollution, and energy demand for cooling.

- City parks that connect people to nature, provide recreational space and islands of biodiversity. Mangroves, dunes and healthy reef systems that protect coastal cities from storm surges.

Case Study of Urban farms, Brussels, Belgium

Brussels has set a target of sourcing 30 percent of its food locally by 2030. The commune of Anderlecht, in the Brussels region, has worked to rehabilitate abandoned commercial sites while also boosting the provision of local food.

The BIGH (Building Integrated Greenhouses) Farms project, which is building a network of urban farms, is part of the way that Anderlecht is trying to deliver these twin goals. BIGH’s design integrates aquaponics into existing buildings to reduce the site’s environmental impact. Farms are linked to the building operation and benefit from any energy surplus, in effect reducing the building’s CO2 emissions.

Such urban agriculture locates food production closer to consumers, increases the sustainability of the value chain and delivers community benefits. BIGH Farms partners with local businesses and growers to make sure the farm’s production is complementary to the existing food supply. And by supporting a circular bioeconomy, such urban farms can catalyze waste reduction and climate benefits. The pilot farm includes a fish farm, a greenhouse and over 2,000 square meters of vegetable gardens. In 2018, it started producing microgreens, herbs, tomatoes and fresh fish.

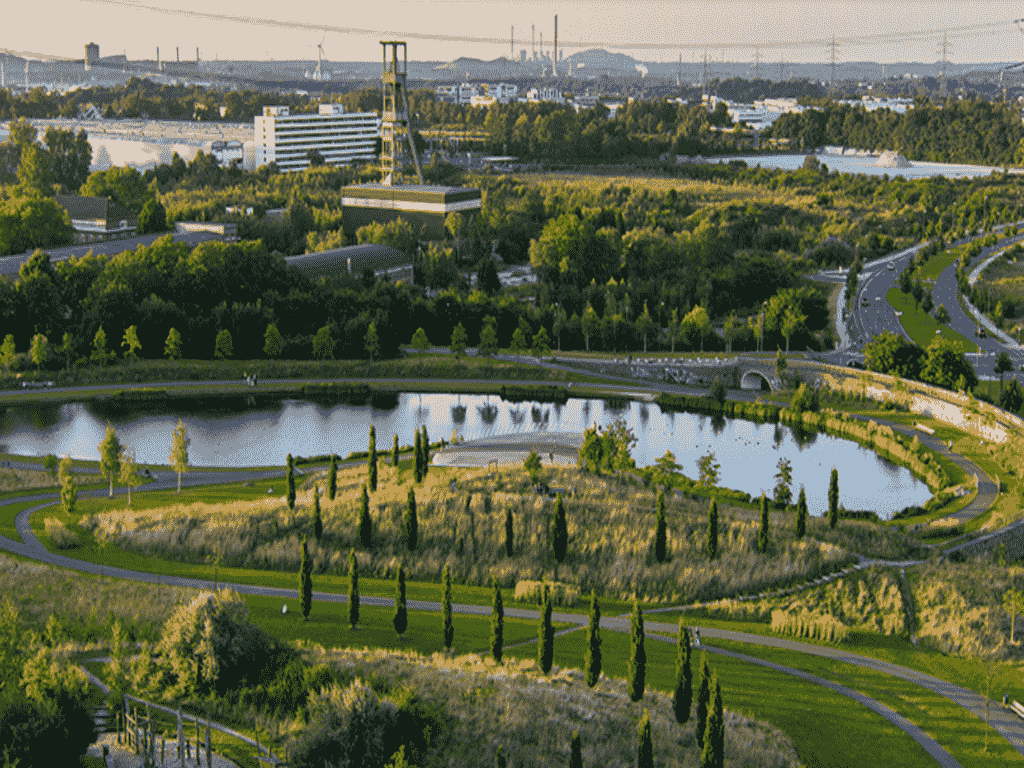

Case Study - European Green Capital 2017: Essen’s transition from gray to green

The City of Essen, located in Germany’s former industrial heartland, the Ruhr Metropolitan Area, has reinvented itself from a gray, industrialized city to a green city with a high quality of life. While the urban landscape is still spotted with relics from its coal and steel past, hundreds of hectares of green space have been created over the past decades through the conversion of disused factory buildings and mining facilities.

The former site of the Krupp cast steel factory, for example, was transformed into a 230 hectares green belt stretching from the city center to the district of Altendorf, while the adjacent industrial wasteland was turned into an 11 hectares add-on to the Krupp Park. The gradual ecological restoration of the Emscher River and its tributaries which historically served as open sewers further contributes to Essen’s goal of enabling every resident to access the city’s green and blue infrastructure network within a range of 500 meters.

By 2020 the conversion of the degraded river system into close-to-nature water bodies will largely be completed. In recognition of Essen’s achievements and high ambitions the city was named European Green Capital 2017 and serves as a role model to other post-industrial cities striving for urban renewal and regeneration.

Situated in a valley with a mild, temperate climate and low wind speeds, the southern German City of Stuttgart is particularly prone to the urban heat island effect and poor air quality. To better deal with these challenges and prepare for a warmer future, Stuttgart has implemented a comprehensive set of nature-based solutions coupled with key regulatory policies and incentive schemes. For example, green ventilation corridors have been created to enable fresh air to sweep down from the city’s surrounding hills.

Prioritizing public health considerations over additional property tax revenues, construction is banned in strategic areas so as not to compromise the effectiveness of these green aeration corridors. A leading pioneer in the realm of green roofs, Stuttgart boasts over two million square meters of vegetated roofs which absorb pollutants and reduce excess heat.

Since 1986, the local government has required any new building with a roof pitch below 12 degrees to be equipped with a green roof – a regulation that was extended in 1993 to encompass all new buildings. Tax incentives and tailored financial programs have further contributed to the city’s green roof expansion strategy.

Case Study - Shenzhen’s Sponge City transition

Shenzhen City, situated in China’s subtropical south, is faced with heavy downpours during the monsoon season and water scarcity during periods of drought. To address the dual challenge, the local government has long turned to nature-based solutions, particularly during the construction of its Guangming New District. Guangming’s People’s Sports Center, for example, is equipped with a green roof, rain gardens and permeable pavement capable of capturing over 60% of annual rainfall.

In 2011, the district was recognized as China’s first low-impact development model town in stormwater management. To further spur the city’s ecological transition, it was selected to take part in the national Sponge City program1 providing Shenzhen with an additional 1.5 billion yuan (205 million Euros) in subsidies over three years. The action plan set up by the local government foresees the re-designing of an additional 256 square kilometers in 24 areas in a water-sensitive way.

The City of Guangzhou, situated in southeast China’s Guangdong Province, boasts a comprehensive network of greenways. The linear green spaces combine scenic trails with green belts for nature conservation. By providing safe infrastructure for recreational and commuter use, the greenway system promotes healthy lifestyles and encourages a modal shift from car use to cycling and walking.

In addition, the creation of the network has increased tourism and stimulated the local economy since its various corridors and nodes connect most of Guangzhou’s cultural and historical sites, museums and recreational facilities. Reflecting the attractiveness of living close to open green space, adjacent property values have gone up by up to 30%.

Reasons for mainstreaming nature-based solutions

Despite growing recognition for the potential of nature based solutions, operationalizing them into policy and urban planning as well as facilitating their implementation requires additional efforts. Key critical aspects to accelerate these mainstreaming processes include:

- Establishing an evidence base for nature-based solutions, for example, by quantifying their ecosystem services and/or assessing their added value and co benefits;

- Advocating for nature-based solutions by communicating their multi-functionality and ability to contribute to various policy arenas such as climate change adaptation, public health, nature protection and economic development;

- Fostering collaboration across the full spectrum of stakeholders such as urban planners, utility operators, municipal officials and residents to ensure cross-sectoral buy-in and commitment for nature-based solution policies and planning guidelines;

- Leveraging conventional sources and unlocking novel mechanisms for financing such as green bonds, adaptation funds, taxes and fees, public-private partnerships to implement nature-based solutions.

References

- Frantzeskak, N. (2018) Seven lessons for planning nature-based solutions in cities. Dutch Research Institute For Transitions, Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

- Nature-based solutions for sustainable urban development. Available from: https://unfccc.int/files/parties_observers/submissions_from_observers/application/pdf/777.pdf[accessed January 23 2023].

- How cities are using nature-based solutions for sustainable urban development. Available from: https://cbc.iclei.org/cities-using-nature-based-solutions-sustainable-urban-development/ [accessed January 23 2023].

- Smart, Sustainable and Resilient cities: the Power of Nature-based Solutions. Available from:https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/36586/SSRC.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y[accessed January 24 2023].

Anastasiia Murzaeva is a fourth year student of Altai State University, Barnaul (Russia). Her major is Landscape Architecture and Environmental Design. My most favorite fields of research are Landscape Planning and Urban Development. Improving the quality of life in both rural and urban spaces, through urban planning and landscape architecture is the main goal for Anastasiia. An important part of her interests is the research of climate, ecology, plants and their interconnection in the anthropogenic environment. Anastasiia uses a contemporary approach while designing landscape architecture projects.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

UDL Illustrator

Masterclass

Visualising Urban and Architecture Diagrams

Session Dates

28th-29th March 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “