New Urbanism and Public Space: Human-Scaled Design and Walkable Community Frameworks

Modern cities that were previously plagued with car-oriented city planning and zoning that caused urban sprawl are now adopting new urbanism to revitalize human-scaled design and walkable neighborhood cultures. It is a complete redesign of neighborhoods as active, non-automotive-centric spaces that allow individuals, rather than cars, to be in the center. New urbanism promotes healthier living, local economic growth, and tight-knit social relationships through mixed-use development, access to green spaces, and functional places of active life. Pedestrian-based planning proposes a viable way out of the city struggling with climate change, congestion, and increasing inequality. Based on landscape design and civic action, it puts an emphasis on inclusivity, ecological stability, and mobility justice. New urbanism also offers a blueprint of the future-ready city that is safer, tolerable, and adaptable to the whims of the dynamic community by prioritizing the experience of the community over the infrastructure.

Understanding the Foundations of New Urbanism

New urbanism is based on the idea that cities should be made for people, not cars. This way of thinking about planning focuses on small, walkable neighborhoods that include homes, businesses, parks, and community centers in spaces that are comfortable for people. At its core, it encourages a lively street life, healthier ways of living, and a stronger sense of community.New urbanism is beneficial to the environment and public health as it makes people get around by walking more and using vehicles less often.

According to a Canadian study at Environmental Health Perspectives (2022), individuals in extremely walkable neighbourhoods had a reduced risk of heart disease or premature death, particularly individuals in low-income communities. Similarly. According to research conducted by the American Heart Association (2023), Walkable infrastructure may help chronically ill individuals who have diabetes or high blood pressure, especially in low-income communitiesMixed-use developments also utilize land in a much better way and prevent the oversizing of cities. It takes 5 to 10 minutes to get what people need in their daily life since everything such as home, business, and cultural place is provided in these neighborhoods.

The Role of Public Space in Urban Connectivity

In new urbanist models, the public space is the pulse of the city. The civic squares, parks, sidewalks, and plazas are built to promote the community interaction, leisure, and social equity. Such areas are not simple through passages; they are places worthy of the definition of the character and identity of a neighborhood.

The green spaces in urban areas cool down cities and have psychological and physical health benefits. Research done by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2023) confirms that the neighborhoods that are within easy reach of parks and other areas that are open have less pronounced stress and better air quality. The restorative therapy that urban nature has on the psyche and stimulating physical exercise, especially amongst the young and the elderly.

Additionally, well-designed public areas are economic stimulants. Smart Growth America’s Foot Traffic Ahead (2023) report found that walkable urban neighborhoods (WalkUPs) in the 35 largest U.S. metro areas generate 2.8 times more GDP per capita than car-dependent neighborhoods, despite making up 6.8% of the population. This difference can be partially explained by the large number of people walking to support local businesses. Walking, shopping, and interacting with others all increase one’s sense of place and belonging.

Source: Website Link

A Case Study of Paris and Its Urban Transformation

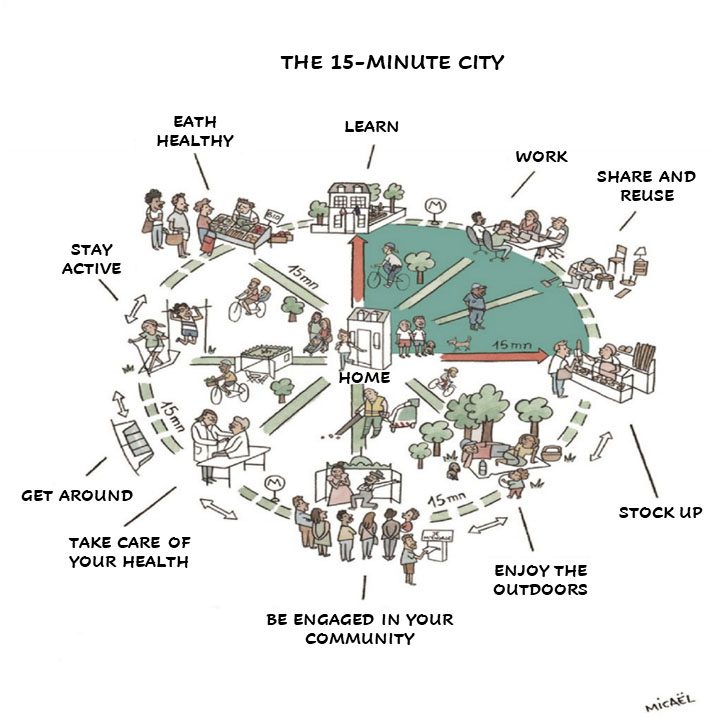

The idea of the 15-Minute City is being consistent with the central values of New Urbanism by shoving the population to receive critical needs and facilities within walking or cycling distances of their houses. Such a strategy will not only contribute to the decrease of carbon emissions but will also build stronger ties between the community. Paris has emerged as one of the proponents of the model, particularly in the COVID-19 pandemic period when rapid alterations in the urban design have been deployed to enhance daily existence.

The projects like the widening of the pedestrian infrastructure and the increase of cycling integration signify the commitment of the city in building a more walkable people-friendly environment. Such alterations seem to have led to a substantial rise in cycling and the consumption of the local economy in these neighborhoods (Moreno et al., 2021). With more cities considering the model, it is important to estimate the social and economic effects of the model and the acceptability of this model. The model is also bound to be dynamic to meet growing needs of the urban communities through continuous assessment and adapting to such needs through flexibility in planning.

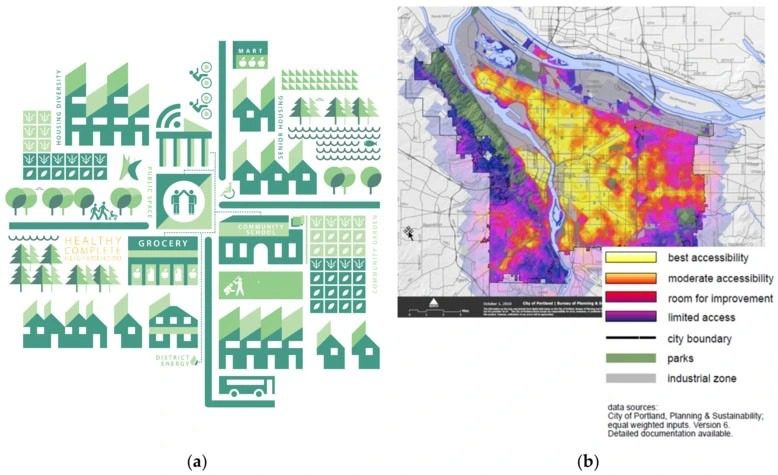

Case Study : The Impact of New Urbanism in Portland

Portland, Oregon came to national attention with its 20-Minute Neighborhoods initiative in 2009 its aim to make 90 percent of residents within reach of basic needs such as grocery stores, parks, schools, and transit available within 20-minute walk or bike distance. In the following decade, the city made the city a walkable place with broader sidewalks, busier transit, and greater availability of local shopping (Simon, 2020).Yet even with these gains in place, the initiative has not resulted in large shifts in vehicle miles traveled (VMT) illustrating that improved infrastructure has done little to change car dependency. Although Portland has above-average levels of biking and public transit use, more policies are required to curb the mode of travel.

The increased residential density around transit hubs has enhanced land-use efficiency and the accessibility to services in the city, contributing to the achievement of broader environmental and public health aims, although the argument of that greenhouse gas emissions decreased by 20 percent is not substantiated in the study (Simon, 2020).Overall, the Portland model has resulted in greater accessibility of communities and is consistent with aspirations of health, economic vitality, and community connection but more fundamental change necessitates more comprehensive systemic interventions.

Benefits of Walkable Communities and Public Spaces

Walkable communities provide valuable features other than a nice appearance, namely, health, the environment, the economy, and social life.

- Improved Health: Research indicates that due to increased walking, residents of walkable communities exercise more and have reduced incidences of chronic illnesses.

- Better Mental Health: Being near or in the park and green spaces assists in making one less stressed and healthier.

- Fewer cars: Less air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions due to decreased car traffic.

- Increased Property Values: Houses that are close to areas where there is walkability reflect better market value since the demand goes high.

- Better Local Economy: Areas accommodating pedestrians increase the foot traffic, which aids the local businesses.

- Improved Socialization: Walkable community places encourage socializing and interaction with the community.

- General Living Standards: Neighborhoods are more places to live in because of easy access to the shops, recreation, or social gathering space.

Challenges and Solutions in New Urbanism

New urbanism is great in its advantages, yet it presents challenges in implementing the plan. The inequalities that tend to intensify in cases of rapid urban growth restrict access to basic facilities and quality spaces in the public areas, particularly, lower-served communities. This difference increases the difficulty of getting the complete benefits of walkable, human-centered communities. Also, a lot of the population is reluctant to change their car-dominated lifestyles, thus hindering the endeavors to facilitate and encourage a pedestrian look and feel.

What should be done to defeat these issues? Very crucial is that policy advocacy and community involvement must integrate. Urban planners needs to integrate the local people so that the construction is aligned with the needs and values of the locality. The money should be invested in more developed means of public transport as this will not only help the shift to the contested model but will also make people less dependent on cars. Turning the attitude of the population towards it by means of encouraging people to consider its long-term positive effects can be successful: better health, sustainability of the environment and social networks. These strategies can collectively eliminate the barriers and facilitate the accessibility to everyone.

Community Engagement and Public Involvement

New urbanism requires community involvement. The probability of actions that would fulfil the actual needs and values of the population to whom they are being built would be much more likely to occur when the residents themselves are engaged in the same process of urban planning. It results in the generation of additional relations in the community, improvement of the degree of satisfaction, and efficient exploitation of the shared areas. Community inclusion also guarantees participation of other voices including the marginalized voices or voices Unheard in the decision-making process.

To help planners get feedback and build trust between local governments and communities, such tools as public forums, surveys, and design workshops (charrettes) are applied. This openness encourages accountability, and people do not have the feeling that they are powerless in their neighborhoods. The vibrant neighbourhoods support and maintain the common grounds and that is what contributes to the places getting the long-term victory. Besides that, the engagement will help in promoting equality in the delivery of green space, transport amenities and basic facilities. The early stages of the urban project include the communities and, thus, can make it more inclusive, equitable, and sustainable for everyone.

Conclusion

A progressive solution to issues facing the contemporary urban resident is provided by new urbanism, which emphasizes humanized and level design of communities or districts with easy accessibility, mixed-use solutions. This philosophy of planning redesigns urban life through its decreasing ability to rely on cars, improving public health, and designing spaces that facilitate interaction, inclusivity, and sustainability. In case studies, 15-minute city and Alexandria, done correctly, new urbanist projects can lower emissions and boost local economies, and enhance livability with easy access to green space and walkable infrastructure.

However, there are still implementation problems, such as the car-oriented societies, social inequalities, and lack of public participation. In order to tackle these issues, inclusive policy-making, better involvement of people, and careful long-term investments in the formation of transportation and infrastructure will be required. Community planning ensures the developments meet the local demands and everlasting wild and stable societal gains. New urbanism principles cannot be chosen; they are necessary now in the era of a growing urbanization process and climate emergency. A reconsidered world based on people rather than cars can create future cities where community is healthier, where people are better connected and more resilient.

References

- American Heart Association. (2023, November 30). For green spaces to be most beneficial to health, they need to be walkable. https://www.heart.org/en/news/2023/11/30/for-green-spaces-to-be-most-beneficial-to-health-they-need-to-be-walkable

- Lang, J. J., Pinault, L., Colley, R. C., Prince, S. A., Christidis, T., Tjepkema, M., Crouse, D. L., de Groh, M., Ross, N., & Villeneuve, P. J. (2022). Neighbourhood walkability and mortality: Findings from a 15-year follow-up of a nationally representative cohort of Canadian adults in urban areas. Environment International, 161, 107141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2022.107141

- Moreno, C., Allam, Z., Chabaud, D., Gall, C., & Pratlong, F. (2021). Introducing the “15-minute city”: Sustainability, resilience and place identity in future post-pandemic cities. Smart Cities, 4(1), 93–111. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities4010006

- Smart Growth America. (2023). Foot traffic ahead 2023: Ranking walkable urbanism in America’s largest metros. https://smartgrowthamerica.org/foot-traffic-ahead-2023/

- S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2023). The benefits of green infrastructure. https://www.epa.gov/green-infrastructure/benefits-green-infrastructure

- Pozoukidou, G., & Chatziyiannaki, Z. (2021). 15‑minute city: Decomposing the new urban planning eutopia. Sustainability, 13(2), 928. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020928

- Simon, C. (2022). Portland’s 20-minute neighborhoods after ten years: How a planning initiative impacted accessibility. University of Washington Research Works Repository. https://digital.lib.washington.edu/researchworks/bitstreams/54e30d81-bae1-4ac5-871a-9e0f779e35a3/download

Varsha Mokal

About the author

Varsha Mokal, an architecture graduate from India with a Master’s in Urban Design from the UK, is passionate about harnessing GIS and AI to shape sustainable, inclusive cities. Specialising in spatial analysis and ecological design, she leverages data-driven strategies to create future-ready urban solutions. Skilled in digital tools and research, Varsha focuses on innovative approaches to energy planning, mobility, and community development. Committed to blending technology, design, and equity, she aims to drive forward-thinking urban projects that build a resilient and smart urban environment.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

Kim Dovey: Leading Theories on Informal Cities and Urban Assemblage

UDL Illustrator

Masterclass

Visualising Urban and Architecture Diagrams

Session Dates

28th-29th March 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “

One Comment

https://morsecodetranslator.best/

thanks share