New Urbanism Perspective on Urban Planning of Singapore

Post-War American Suburbs

In post-World War II United States, a combination of extreme housing demand, new federal loan programs designed to increase the accessibility of automobiles and homeownership, and the conception of new infrastructure and road-building public works projects sets the stage for one of the most ground-breaking urban planning developments in recent history ¬– the proliferation of the suburb. Incentivized by federal infrastructure projects like the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 and lowered automobile prices and upheld by the vision of the American Dream, the rise of post-war American suburb communities transformed our perceptions of cities and communities.

The suburb was designed as an alternative to the congestion, over-crowdedness, and generally poor living conditions usually associated with pre-war American cities. These suburban planning frameworks took the form of low-density residential communities characterized by single-family zoning developed at the outskirts of the city ¬– packaged with the promise of tranquillity, ample space, and maximum freedom. These developments helped usher in post-war economic prosperity, with 83% of all population growth between 1950 and 1970 occurring in suburban places, which enabled governments to develop at unprecedented rates and distances. In this time, America’s suburban population nearly doubled, residing in communities developed further and further into the peripheries of the city.

This rapid suburbanization led to, what critics argue is, one of the most catastrophic planning phenomena in modern history ¬– urban sprawl. This builds upon low-density, single-family zoned communities and is characterized by the excessive and unbridled consumption of land, the rigid separation of land uses, and an overdependence on the automobile. These undefined development patterns, absent of clearly delineated edges, have and continue to threaten pristine habitats and wildlife and exacerbate construction-related water and air pollution. In addition, the vastness of these developments and subsequent overreliance on automotive transport bring about numerous adverse physical and social effects including health-related risks, loss of key heritage spaces, loss of diversity and social dynamism, loss of community engagement, etc.

The Core Principles of New Urbanism

The New Urbanism movement, which originated as a counter-measure to urban sprawl, promises a return to pre-war urban planning ideals. Human-centric, comprehensive, compact, and sustainable architecture is at the heart of New Urbanism. Urban design that incorporates active transportation and vibrant public areas achieves this. This inward emphasis, which reflects community needs and preferences, contrasts with the uncontrolled suburban sprawl. Its ten Core Principles are: walkability, connectivity, mixed-use & diversity, mixed housing, quality architecture & urban design, traditional neighbourhood structure, increased density, smart transportation, sustainability, and quality of life.

For this Article, the 10 Core Principles will be reduced to 5 Core Values of New Urbanism. They are interconnected and subdivided for specificity.

1. Traditional Neighbourhood Structure (TNS)

The post-WWII suburban neighbourhood structure had deeply problematic and widespread consequences that went beyond land acquisition and environmental degradation but involved the increasing failure of our neighbourhoods to sustain and reflect the needs of their communities. The New Urbanism movement seeks to bring about a revival of the traditional neighbourhood structure, that is, the neighbourhood structure most prominent in the United States between the 1600s and World War II. The following are four examples of TNS guidelines.

It must first have a clear centre and edge. This may sound simple, but it requires intelligent design within spatial limits, something most suburban schemes ignore. This ensures precise urban planning that fosters local cultures, tastes, and themes. It also helps establish the city or neighbourhood centre as a significant meeting point, adding to the space’s imageability. Following this, public places must be emphasised and developed ideally at the centre. These critical nodes should correctly reflect and serve the neighbourhood. Community building and dynamic gathering areas require these. The third rule focuses on the importance of having a variety of services, activities, and amenities within walking distance. Improved relationships with our constructed form.

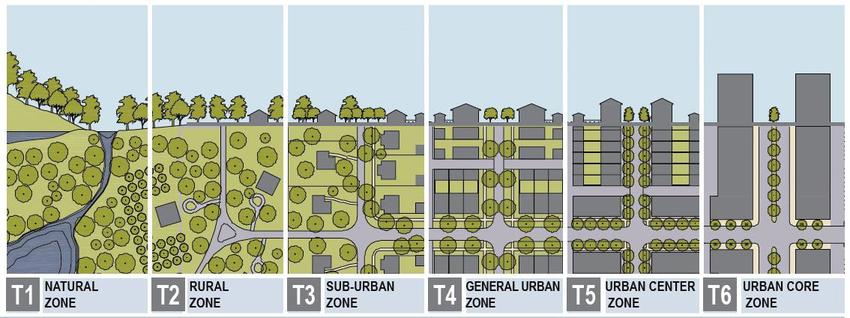

The New Urbanism aspires to resuscitate the TNS, not to reproduce it. The movement distinguishes itself by emphasising the framework’s adaptability to various typologies. The deconstruction of basic TNS rules and subsequent translation into distinct urban densities is clearly defined. The fourth guideline is the urban-rural transect. The Transect, designed by New Urbanist Andres Duany, divides the urban-rural spectrum into six zones. This presents a developmental framework with embedded TNS ideals. To encourage dynamism, urban zones should be mixed-use, with commercial, business, and residential zoning, as opposed to the tight separation of land-uses found in suburban towns. Moreover, urban zones must support high-density settlements vertically rather than peripherally.

2. Walkability & Diverse Transportation Nodes

One of the New Urbanism’s biggest qualms with post-war developments is the overreliance on automobiles of suburban communities to access amenities (e.g. groceries, open space, sports, etc.) and services (e.g. educational institutions, banking, community centres, etc.). Instead, it measures the planned city at the human-scale, in the length of walking minutes, thus putting the human at the forefront. It envisions neighbourhoods that are compact and thoughtfully planned, with amenities and desires located within a 10-minute walk from home or work. With this as a benchmark, planners and urban designers can arrange the placement of key services to encourage walkability and accessibility while decreasing automobile trips and reducing congestion.

In addition, it encourages the holistic design of transportation systems to promote a high-quality, and thus appealing, network made up of a diverse range of transportation nodes. Active transportation such as walking, cycling, and rollerblading are prioritized followed by public transportation such as buses, subway trains, and streetcars.

3. Environmental Sustainability

Construction and development are major contributors to the waste and environmental degradation associated with the design of our cities. Urban sprawl encouraged unplanned, undefined, and unsustainable peripheral growth that tore through natural reserves, dismantling key ecosystem networks and destroying habitats and wildlife at an unprecedented rate. In addition, the waste and fossil fuel emissions incurred through the over-implementation of automobiles and haphazard planning contribute towards the looming threat of global climate change.

The New Urbanism has addressed this in two ways. First, through the preservation and protection of natural assets that are integrated into the design of neighbourhoods, bolstering these assets to encourage healthier, more environmentally engaged communities. Second, through the elimination of unnecessary waste and fossil fuel emissions through a decreased reliance on driving as well as eco-friendly and more energy-efficient technologies.

4. Diversity

The suburbs can be characterized by rows and rows of identical detached single-family homes framed by their respective white picket fences. The residents of these communities were predominantly white and middle-income. These communities lacked both housing and resident diversity. The New Urbanism movement sees diversity as an asset, one that encourages dynamism and enriches quality of life. Therefore, first, there must housing diversity – that is, a range of housing typologies (e.g. pricing, homeownership vs. tenant, size, etc.) that increase accessibility and accommodate for varying living circumstances. Second, there must be incentivization or regulatory programs that oversee diversity in resident background (e.g. race, gender, disability, income-level, culture, etc.) While diversity can make decision-making and city-planning a more challenging endeavour, the input and varying perspectives from a diverse population is invaluable in ensuring our cities are accessible and support all of its residents.

5. Place-Making

The New Urbanism model values place-making above all. This is the art of strengthening a space’s cultural, social, and physical identity and imageability through a profound sensitivity for its historical roots and a commitment to empowering it in its evolution. Place-making is most effective when it is a result of collaborations among varying stakeholders and a co-creation by its community. This is the magic that feeds into the vibrancy, appeal, and experiential significance of our world’s most beloved spaces.

Critiques of New Urbanism

The New Urbanism movement is concerned with the belief that neighbourhoods that are designed at the human-scale, are thoughtfully planned to maximize community connections, and increase accessibility through diversity and connectivity will increase one’s quality of life. While it is generally understood that New Urbanism’s criticisms of suburban developments and its subsequent proposed alternatives, in theory, are significant, critics question the feasibility and validity of these ideals when realized in built towns and neighbourhoods.

The most common critique is these built New Urbanist towns are guilty of perpetuating the very ideologies it aims to disrupt and thus become “suburbs in disguise.” While these new towns are considerably more dense, some are still predominantly allocated towards single-family homes, zone for single land-uses, and remain reliant on automobiles as the primary source of transportation. Its harshest critics claim that the New Urbanist movement has backfired and amounted to little more than a glorified marketing campaign, prone to a superficial packaging of developers as suburbs in disguise. In addition, the New Urbanism framework is challenging to apply to pre-existing neighbourhoods due to most interventions requiring a complete reworking of its design.

Since its rise in prominence in the 1990s, the movement has made tremendous strides in shifting the planner’s gaze towards community-building. But it is clear that it is still in its infancy and requires considerable refinement and further testing to provide a viable alternative to the American suburb.

Singapore’s City Planning Frameworks within the New Urbanism Model

In less than 60 years since its independence in 1965, the small island city-state of Singapore has achieved urban planning feats at a rate previously unheard of. Referred to many as the “best-planned city” in the world, Singapore is revered by planners for its careful negotiation of widespread affordable housing, green spaces, self-sustaining new towns, and world-class transportation infrastructure. According to Dr. Liu Thai Ker, often credited as the chief architect of modern Singapore, this was a result of the development of long-term planning visions set out at the onset and the political will and power to execute these visions with minimal bureaucratic roadblocks.

How effectively do these world-renowned Singaporean planning frameworks meet the standards set in the principles of New Urbanism? While Singapore did not experience rapid suburbanization, instead housing over three quarters of its population in squatter communities, this comparative exercise sheds light on the similarities involved in cities in different contexts as they grow and pursue more sustainable, community-cantered design practices.

1. Traditional Neighbourhood Structure (TNS) and the Housing Development Board (HDB)

After its independence in 1965, ratified in the 50-year vision in the Concept Plan 1971 and the 15-year short-term goals in the Master Plan 1958, the city-state required thoughtful and efficient government programs to execute its vision for its people. These programs were designed with the future in mind and heavily integrated Singapore’s core values. One of these key values was housing and, eventually, homeownership for its citizens. This resulted in the conception of the Housing Development Board (HDB). It is involved in the subdivision of land at the region and neighbourhood scales. These subdivisions were designed to decentralize development while providing housing, amenities, and services to support the locality.

A neighborhood or regional edge is defined by the HDB as well as its relationship to the central space. These central spaces are usually natural (e.g. parks or natural land), shopping centers, or key urban features (e.g. harbourfront). The lack of organic dynamism and spontaneity of beloved public spaces makes these feel overly curated and picture-perfect. Despite this, these areas offer a wide range of amenities and services. Aside from job opportunities, which are concentrated in the Central Region, neighbourhoods are generally responsive and adaptable.

This framework generally follows the specifications of zones within Andres Duany’s Transect but begins to blur the lines between each zone. For example, it merges vertical, high-density public housing developments (designated in Zone 6 – Urban Core Zone), with access to ample natural open space and greenery available at Zones 2 to 4. These public housing projects are not stigmatized as they are in the United States – where these are commonly seen as derelict, neglected, and unsafe clusters of the city – but housing the vast majority of the Singaporean population (over 81%). Singapore walks this balance quite effectively and creatively merges elements of the urban, suburban, and rural zones. Furthermore, while these neighborhoods usually provide a wide range of activities, most structures are not mixed-use and zoned by land use. That being said, these elements are weaved cohesively with each other.

2. Walkability and Public Transit over Private Vehicle Use

The neighbourhoods are designed for pedestrians. Within a 10- to 15-minute walking radius are hawker centres, coffee shops, community centres, sports facilities, and government collection points. These self-sufficient neighbourhoods (excluding employment opportunities) were clearly the result of meticulous master planning and careful consideration of all local residents’ needs and desires.

Work opportunities tend to be concentrated in the island’s central and southern regions. Buses, rail transit, and light rail options serve these longer commutes. While these cities have a variety of transportation options, most residents must endure hour-long commutes. These reduce private vehicle use and congestion while limiting walkability.

The high cost of car ownership discourages private vehicle use. Prospective car owners must pay a 20% Excise Duty Tax on top of the market value and a Certificate of Entitlement nearly equal to the car’s cost. This reduces private vehicle ownership and, coupled with increased public transportation investment, offers alternatives to the automobile.

3. Environmental Sustainability for Human Benefit

The city-state’s relationship with its natural resources is complex. In the same way that post-war American suburbs tore through the peripheries of the city to accommodate for the growing demand for housing, so too did Singapore through the Housing Development Board (HDB) and its programs. Natural areas needed to be reclaimed and developed at a staggering rate to realize the dream of housing for all. More than 95% of the city-state’s vegetation has been cleared. The key difference between these two approaches was in the strategic planning involved – Singapore’s unilateral vision versus the staggered and decentralized development by a mix of stakeholders in the American suburb.

Preserving natural areas, protecting key wildlife and habitats, and bolstering ecosystem services are integrated into Singapore’s urban planning vision, embodied in the Singapore Green Plan 1992 and 2012. Lush green spaces and diverse street tree planting are present throughout the entire island. One of the most ambitious projects is the Park Connector Network (PCN) which links island-wide green and natural spaces through over 300km of green corridors.

While these endeavours promote a symbiotic relationship with nature, it is clear, thus far, that the protection and conservation of these resources are only justified when they provide benefit to humans. This human-centric approach perpetuates the notion that these spaces hold no inherent value outside of its use to humans. This holds true to its continuous prioritization of development. In the process lush, untouched natural spaces, like the Clementi Forest, are slated for development whenever it is demanded.

4. Diversity of Housing and Demographic

The HDB program, which houses over 81% of Singapore’s population, is iconic to the island’s cityscape. Clusters of white high-rise towers with porous circulatory walkways identified by monochromatic accents along its façade are a dime a dozen on the island. While these are homogeneous in structure, they cater to a wide range of living circumstances. In contrast to the single-family zoning that characterized the suburbs, HDB flats are available at different pricing, location, and unit sizes, with the availability for built-to-order flats on a waitlist. In addition, high-rise towers, colloquially known as “HDBs,” are important in connecting residents of different races, cultures, and socio-economic backgrounds and play an integral role in the fostering of a diverse and rich community. To avoid the development of “racial enclaves,” as present in the public housing projects of the United States, the Ethnic Integration Programme (EIP) was introduced in 1989. This program ensured that each HDB housing complex accurately reflected the racial and ethnic proportions of Singapore – that is, there exists a quota for how many members of each ethnic background could claim housing in each estate. While this is an extremely forward-thinking approach, programs like these can only be achieved in heavily regulated spaces.

This leads to the failings of diversity in Singapore. The values of homeownership, young married couples, young families, strong familial ties, etc., which Singapore holds dear, are parts of the reason why the city-state has so effectively and precisely planned its cities and communities. Problems emerge when people groups, in their diversity, do not fit the Singaporean mould (e.g. tenants, single and unmarried individuals, complex relationship with family, etc.). These people can fall through the cracks and be marginalized by their own communities. For example, while the statistic of 90% Singaporean homeownership is often met with praise, little is said about residents who, by their own volition or not, remain renters. While there are options for rental flats in Singapore, most are old and many have been demolished to make room for housing estates. In the same way, only married couples can apply for built-to-order flats, the most affordable HDB option. An unmarried individual, therefore, has limited options and often must resort to rooming in rental flats or residing with family. The people groups that exist in these fringes have an invaluable perspective which must be empowered and heard in decision-making. These cases prove that while Singapore is revered for its planning and strong core values, it is not beyond reproach.

5. Place-Making

Singapore masterfully curates memorable, dynamic, and picturesque places throughout the city. These are often key public spaces on the island, have clear identifiable landmarks, and host a wide range of activities, restaurants, and viewpoints. These spaces tend to cluster in the Central Region of Singapore. For the rest of the island, community and place-making rely on the councils and local Members of Parliament (MP) to tap into local culture, grow identity, and support the strengths of their respective localities.

These factors are challenging to assess in theory and rely on personal experiences. To speak from my personal experience and locality, Bukit Panjang offers access to nature, a variety of transportation options, ample amenities, sports facilities, and overall provides a good quality of life. Its representatives are familiar with its demographics and subsequent assets and bolster them to work towards community building. For example, my mother-in-law, who is an avid chef and baker, has found a place in the locality’s platform for home bakers and cooks, Bukit Panjang Sedap!, and enabled her to share her talents with her community. These are the elements of place-making that are vital – the experiential, social, and physical aspects of our spaces that make us feel integrated and connected.

The Future of the Singaporean Planning Model

The Singaporean approach to city planning warrants the widespread praise it receives. In less than 60 years, the island city-state has masterfully implemented extremely effective housing programs, successfully negotiated land scarcity and strategic development, and made a name for itself as a global metropolis. Its vision for walkable decentralized neighborhoods supported by mass transit networks and filled with ample affordable housing stock was beyond its time. With that being said, the Singaporean planning model has evident shortcomings. As with the New Urbanism model, the Singaporean planning model remains in its infancy and requires tremendous growth.

This model will benefit greatly from the development of rigid and holistic community engagement. The thoughtful engagement of key perspectives previously left out of important discourse ensures that all people groups are heard and represented. Authentic community-led discourse is an invaluable asset that can only enrich, enliven and further beautify our experiences of cities.

About the Author

Ivanne Cheng is currently a student at the University of Sydney pursuing a Masters in Urbanism specializing in Urban Design. He wants to help shape cities towards becoming more thoughtfully designed, environmentally sustainable, and reflective of the needs of their inhabitants. He enjoys hiking, playing Smash Bros., Jiu-Jitsu, and giving his two dachshund dogs the attention they deserve.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “