Post-Anthropocentric Urbanism: Designing Future Cities for More -Than-Human Worlds

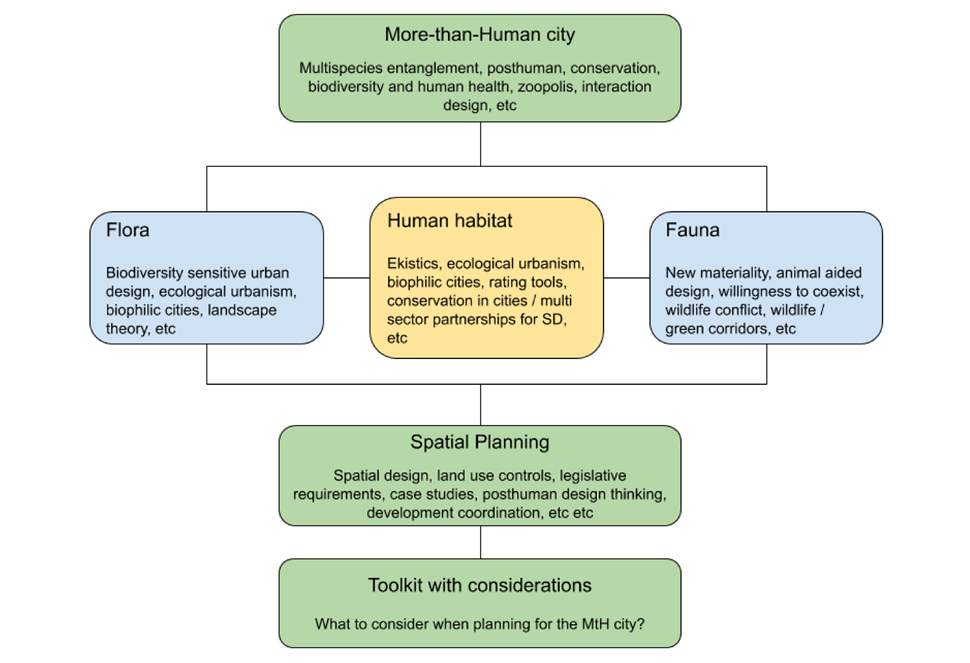

This article explores the shift from anthropocentric urbanism where human needs dominate city planning to a post-anthropocentric approach that embraces more-than-human urbanism. As cities grow and environmental crises intensify, traditional development models have proven inadequate, often resulting in habitat loss, biodiversity decline, and fragmented ecosystems. In response, new strategies are emerging that treat cities as shared habitats for both human and non-human life. The article highlights methodologies like Animal-Aided Design (AAD), which integrate species needs directly into planning processes, and discusses the critical role of urban planning in embedding ecological thinking across scales.

A case study of Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park in Singapore illustrates how nature-based infrastructure can regenerate ecosystems while improving urban quality of life. The article also reflects on challenges such as the lack of practical frameworks and the need for a cultural mindset shift among planners and communities. Finally, it argues that sustainable urban futures require compelling, net-positive visions where cities actively restore ecological systems. These visions must be grounded in local strategies, particularly at the neighborhood scale, where ecological infrastructure, public services, and community engagement can converge to build inclusive, regenerative urban environments for all forms of life.

Anthropocentrism and Post-Anthropocentric Urbanism

Anthropocentrism assumes that humans are the most important beings on Earth. This belief has shaped cities to prioritize human needs above all else, often at the expense of the environment and other species. As a result, urban development has largely excluded non-human life from the design of public spaces and infrastructures. Many researchers have linked this human-centered mindset to the current environmental crisis.

This crisis is especially visible in urban areas. The expansion of dense street networks and infrastructure has fragmented ecosystems, increased wildlife mortality, and degraded forests to make room for residential and commercial development leaving behind ecological damage and increasing vulnerability to climate impacts.

In response, a post-anthropocentric approach is gaining momentum. This perspective invites to see cities as shared ecosystems, where human and non-human life coexist. Rather than focusing only on human needs, it calls for inclusive, multispecies urbanism promoting long-term sustainability and more equitable relationships with the natural world.

Towards Sustainable Urban Development

The environmental challenges caused by rapid urbanization demand a rethinking of how live and design cities. Habitat loss, declining biodiversity, and social inequalities show the limits of traditional planning approaches. To move toward a sustainable future, urban design must involve collaboration between planners, ecologists, designers, and local communities and recognize that both human and non-human life matter.

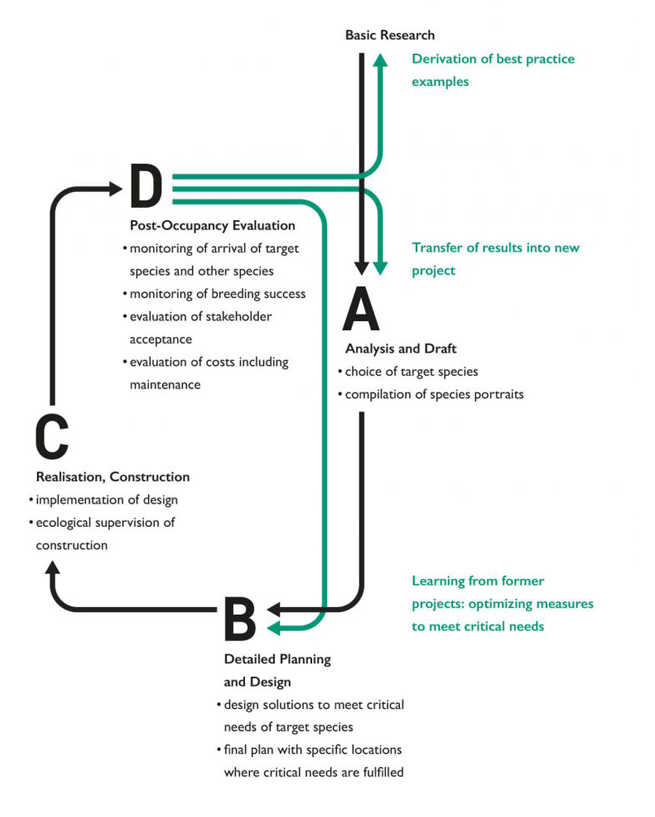

The more-than-human approach supports this shift by fostering connections between people and the ecosystems they inhabit. A strong example of this is Animal-Aided Design (AAD), a methodology that incorporates the needs of specific species directly into urban projects. It starts with analyzing the site and creating “species portraits” that identify each animal’s habitat needs, behavior, and interactions with people.

These needs are then integrated into the design, ensuring space for food, shelter, and reproduction. AAD doesn’t only improve biodiversity it also reconnects people with nature and opens possibilities for rewilding the city.

Source: Website Link

Strategies for Integrating the Natural World into Future Cities

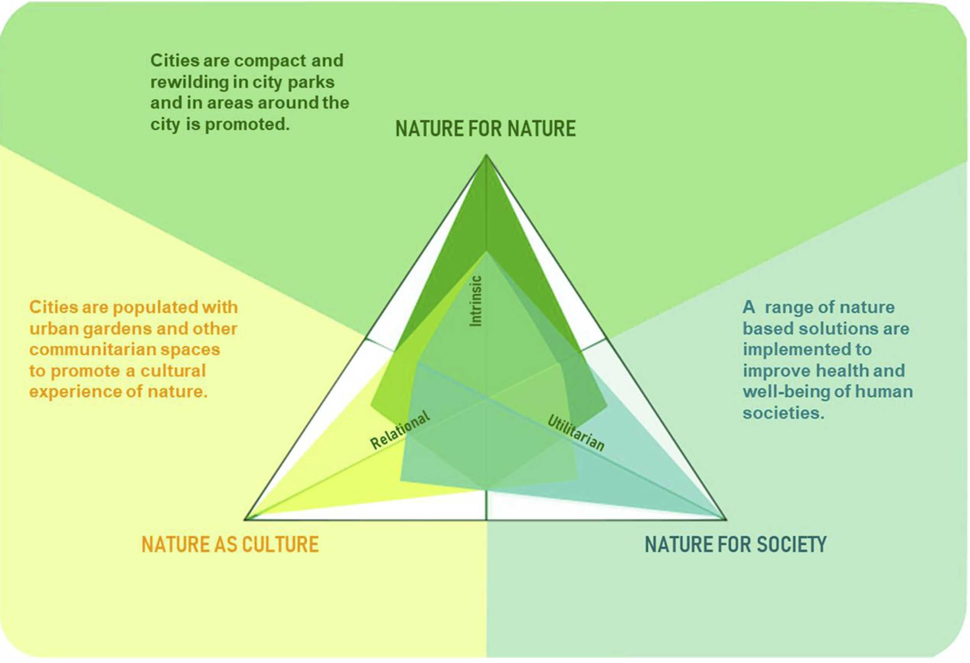

Planning is a key tool in shaping cities that are both sustainable and inclusive. To support more-than-human futures, planning must go beyond regulatory control and adopt ecological values at its core. This means developing policies and guidelines that work across scales from zoning laws to transportation systems while recognizing the interdependence between people and nature.

Bringing the natural world into urban life offers numerous benefits. Green spaces help manage water, reduce air pollution, and improve public health. Preserving habitats and creating ecological corridors strengthens biodiversity and allows wildlife to move safely through urban landscapes.

At the same time, strategies such as urban forests, green roofs, and vertical gardens create multifunctional spaces that support both ecosystems and human well-being. Encouraging local food production through rooftop farms and community gardens strengthens community ties, while walkable neighborhoods and improved transit systems help reduce environmental impacts. When planning aligns with ecological thinking, cities become places where life of all kinds can flourish.

Case Study: Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park

Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park in Singapore is a breakthrough example of integrating ecological and social infrastructure in a dense urban context. Completed in 2012, the project transformed a 2.7 km concrete canal into a naturalized river, reimagining the relationship between water and landscape as a single, cohesive system.

Rather than treating the park and the water channel as separate elements, the design process centered water as the core of the park’s identity. This allowed the project to strengthen the relationship between people and nature through a multifunctional space that manages floods, treats water, enhances biodiversity, and offers a high-quality recreational area for a growing population.

While the park responds to community needs by including walkways, bike paths, and public amenities, it also reflects a post-anthropocentric vision. According to research from the National University of Singapore, biodiversity increased by 33% after the river was naturalized. Visitors doubled from 3 million to 6 million per year highlighting how ecological design can also enrich social life. This case shows how urban spaces can benefit both humans and the environment when designed as interconnected systems.

Challenges and Opportunities

Shifting toward more-than-human urbanism is not without its obstacles. Many experts note the lack of practical tools, planning frameworks, and institutional support to fully implement this approach. There’s also a need to rethink how sustainability is defined moving beyond metrics to include ethics, empathy, and care for all species.

But these challenges come with opportunities. Embracing a more-than-human lens can spark innovation in how plan, build, and inhabit cities. It encourages planners, policymakers, and communities to share space with other beings and acknowledge their role in the urban environment.

At its heart, this approach is about inclusion and respect. It calls for a mindset shift one that values coexistence over control, and justice over convenience. More-than-human urbanism invites to imagine cities as shared habitats, where all forms of life are seen not as obstacles, but as essential parts of urban vitality.

Conclusion

As urbanization accelerates, cities must be reimagined as spaces that not only think about human life but actively contribute to the restoration of ecological systems. The more-than-human approach challenges dominant anthropocentric planning by promoting inclusive and regenerative urban environments. where urban interventions support ecosystem recovery, reduce carbon emissions, and foster long-term resilience. This perspective reframes urban design as a force for environmental harmony, encouraging planners and designers to move beyond minimizing harm and toward generating positive ecological outcomes.

Translating these visions into practice requires working at scales where change can be implemented effectively. The neighborhood offers an ideal context for integrating ecological strategies with public services, infrastructure, and community participation. At this scale, can take root, shaping everyday life and reinforcing urban sustainability. By embedding more-than-human thinking into neighborhood planning, cities can become environments where human and non-human lives are not only acknowledged but supported coexisting in ways that are restorative, inclusive, and future oriented.

References

- Luis Jimenez.(2024).Reimagining Cities: A More-Than-Human Approach to Sustainable Urbanism. From: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/reimagining-cities-more-than-human-approach-urbanism-luis-jimenez-v-mnwcc/

- Walter Fieuw, Marcus Foth, Glenda Amayo Caldwell. (2021). Towards a More-than-Human Approach to Smart and Sustainable Urban Development: Designing for Multispecies Justice. Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane.DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020948

- Fabiano Lemes de Oliveira. (2024). Nature in nature-based solutions in urban planning. Politecnico di Milano. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2024.105282

- Christian Albert, Mario Brillinger, Paulina Guerrero. (2020). Planning nature-based solutions: Principles, steps, and insights. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-020-01365-1

- Animal aided design. From: https://animal-aided-design.de/en/method/

- Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park, Singapore. From: https://henninglarsen.com/projects/bishan-ang-mo-kio-park-and-kallang-river

- Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park, Singapore. From: https://www.planning.nsw.gov.au/government-architect-nsw/case-studies-public/bishan-ang-mo-kio-park-singapore

Juliana Ocaña

About the Author

Juliana Ocaña is an architect, with a Master’s in Urban Design from the National University of Colombia. She has explored how public space and building interfaces shape inclusive and vibrant cities through research, design, and community-oriented work. Her interests lie in integrating digital tools with contextual design to strengthen the relationship between people and place. With a human-centered and exploratory approach, she aims to reimagine urban environments in more adaptive and meaningful ways.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “