Recalibrating Living Dimensions of Heritage Sites

Originality of Heritage

UNESCO and its Heritage Conservation Committees have been working ceaselessly to conserve, safeguard, and list World Heritage Sites, yet more than 95 percent of these sites and buildings remain unexplored. The historic core of society has been a constantly shifting phenomena, adapting to changing societal dynamics. The way people move through such areas varies as a result of changing cultural, political, and economic ideas. These social shifts have tainted the historic structures that have been built, and each passing era imprints its impressions on these structures, making them a part of their history. Similarly, they are either observed in their original form of operation or get remolded in an alternate functioning pattern depending on the variable on changes.

Changes Impacting the heritage

1. Living dimension of heritage site

The immediate context of the heritage site and the locals residing in that area becomes an integral part of the evolution of the heritage site. Defining the term “local community” can be ambiguous, however, one can understand the local, national and international community as invisible concentric circles surrounding a heritage site. The scale of these zones varies with each structure but the fact that the local community impacts the most on the tangible and intangible content of a heritage site remains consistent. The local community associates itself in multiple manners with the heritage site activating it and making it a living heritage space. The dwelling community associated with heritage site are one permanently residing or using that space, giving that space a new identity. Whereas evolving community is one that alters the context of the site modifying its social and cultural value.

2. The evolution with Urban fabric

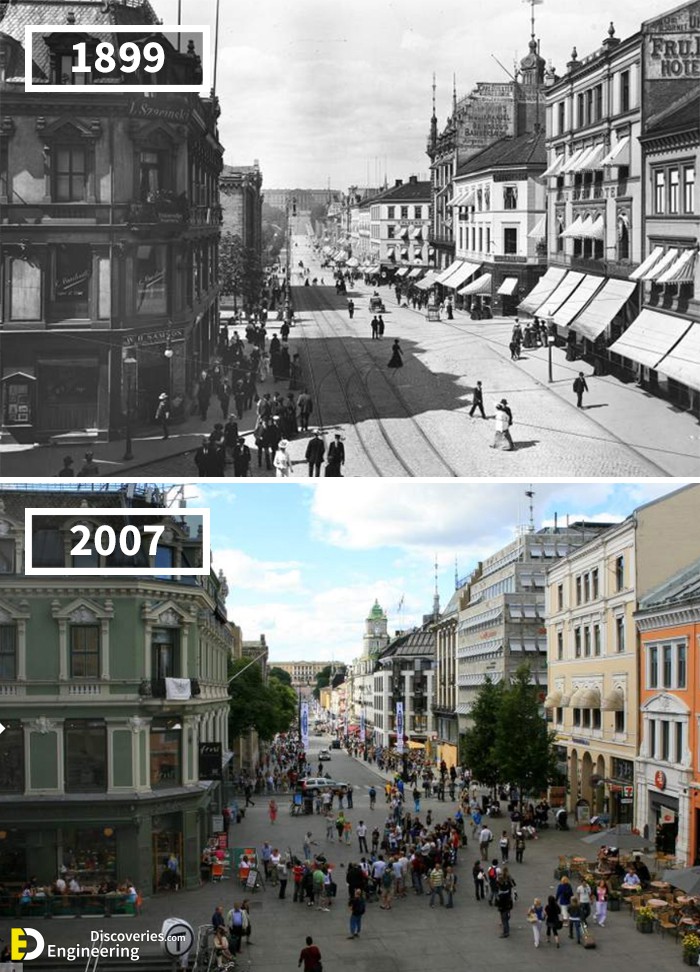

With accelerating globalisation, urban sprawl is an inevitable scenario that leads to a constant modification of urban demographics. Such urban growth and the accumulation of economic activities have a linear relationship; with the change in urban demographic, the socio-economic pattern also gets altered. People ignore their identities, seeking adequate services and a better lifestyle leading to the disappearance of existing urban fabric that creates an undefined urban pattern.

The unprecedented shift in the urban pattern also disturbs the historic identity of the heritage site. As the culture and the demographic surrounding the historic site is altered there is huge change observed in the significance of these landmarks. These landmarks are often neglected or their functionality is deteriorated to adjust with the changing urban fabric. The functionality of these heritage sites is an integral part of its historical attribute, thus the changing functionality of these spaces shapes its identity adding a new dimension to its historical narration. The way people navigate through these historic sites and use these spaces contributes to its living significance in the context, however as the functionality changes it impacts the people’s perspective of the space, disrupting the way people have associated with it throughout its existence.

3. Time and evolvement

Time is the fourth dimension of a structure, an implicit factor that projects itself on the building, changing its identity, appearance, and significance. A direct relationship is observed between the sense of time and the building evolution through time. The historical site is embedded in that context for the longest time has aged through the changing scenarios. With the passage of time external and internal factors equally contribute to moulding its identity into its present form. The transformation of its surrounding context, functionality, material, culture, and user engagement are variables that impact the tangible and intangible notion of the structure. The timeless character of the heritage site is co-related to the temporal approach of ancient buildings that leads to a pluralistic attitude toward their physical decay. Thus a building transforms through various variables over time, it is significant to understand the status of the building and treat it accordingly rather than forcing the structure to reshape in its original form, which might be even impossible in certain scenarios.

4. Change due to conservation legislation and political background

It becomes increasingly important to recognize the living dimensions of heritage sites and facilitate appropriate strategies to sustain the life of the past for the people of the present. Conservation approaches, on the other hand, are quite often simplistic and linear in comparison to the much more complicated living dimension at some heritage sites. It involves various conservation committees working in layered fabrics on different stakeholders. These strategies are modelled into two relatively apparent approaches, namely, the Material based approach and the Value-based approach.

5. Material-based approach

It refers to the ability of organisations at all levels, from international to national, to systemize conservation methodologies for various heritage sites. These established set criteria are manned by conservation professionals and political officials, but it also highlights the potential need for review as the state of heritage sites changes. In many cases, marginalised stakeholders and communities are not considered in the forefront of the framework. The rigidity of these criteria may not meet the demands of the site, resulting in ambiguity among stakeholders and a decline in the site’s intangible heritage as more focus is driven to preserve the structurality and materiality of the site. This results in drawing cracks between the intangible and tangible patterns of heritage culture. Also its dependency on state and country funding may not persist in accordance with the experts in the long term. Non-western phenomena (religious/communities) of management and site practices are not given much relevance resulting in disassociation of the people of the community with the heritage. Such weakness opens the discussion on the effectiveness of the Material-based approach and its formative layering.

6. Value-based approach

The living heritage needs to be catered to in a sensitised method, respecting all the attributes contributing. Standardisation of heritage guidelines and regulations cannot suffice in totality. Value-based approach blurs such lines to amalgamated fabrics of consideration to look beyond a standardised structure. It propels values of communities and non-westernizing techniques that the site and its historical background adopt to manage and synchronise its agility with time. It allows the operation of the past (religious, political,social) or the evolved pattern of functionality to continue with professional inputs and systems aligned by experts and conservation authorities. This ensures continuity of cultural intangibility. Marginalised communities and stakeholders groups play a crucial role in their extrinsic and social procedures. A values-based approach seeks to engage all stakeholder groups early and throughout the conservation process, and to resolve conflicts that inevitably arise between them while ensuring the subjectivity and equity of conflicting stakeholders and different values.

Relevance of historic sites

The heritage sites have long survived as a living monument in their context, resisting the changes implemented on them through passing eras. However, it is inevitable to maintain its originality with various social, cultural, political, and economic factors acting on it over time. The empress market situated in Karachi and the Watson Hotel in Bombay are the epitome of such heritage structures that are rendered by these changes. The two structures are located miles apart in completely different contexts, but they resonate through their historical attributes. The structures were built by the British, during their ruling period in the Sub-continent. They represent the glorious Indo-British era, simultaneously narrating the post-partition evolution of the structure that occurred due to the changing power dynamics and change in functionality.

Empress Market - Karachi, Pakistan

Empress Market is the oldest market of Karachi, built during the 1880s in honor to commemorate Queen Victoria, Empress of India. The stone structures represent the Indian colonial era through its architecture language that is a mix of Roman and Indian architectural styles. The dominating presence of the structure overshadows the surrounding market spaces making it a standing landmark for the locals. The market has experienced a physical and spatial change that aligns with the urban development of the Saddar Bazar. Post-partition immigration and the influx of refugees during the war in 1960 and 1970 has made the historical vacant building in Saddar a potential zone to accommodate them. As the elegant market of Saddar changed into informal housing and warehouses likewise the nature of Empress market also evolved. Pre-partition; the market was known for housing expensive pet shops but soon after partition it turned into a fruit bazaar. Till date that building has existed as a famous fruit bazaar of the city, it has almost become a part of the building’s identity.

Empress market was once known as an elegant market that housed expensive pet shops, but the identity of the building has evolved as the community surrounding it has transformed. Saddar, once known as the most sophisticated locality of Karachi, has been overcrowded by refugees and immigrants due to which the identity of the market was converted into an informal market. The informality of the market attracted vendors from all over the city since it was an established market that provided them a build market platform. As the dynamic of the sadar bazaar changed, thus the local community surrounding the empress market changed. This change of the urban pattern and the economical status of the locality swelled up into the empress Market periphery. Soon the empress market was dominated by the fruit vendors, it was occupied by the informal vendors replacing its original identity of the expensive shop. Thus, it’s almost an unconscious process whereas the local community surrounding the structure changed thereafter the functionality and the use of the statue also transformed. The living heritage structure is living with its time.

There’s a certain level of romanticism associated with the concept of ageing, ageing is not always the decay or deterioration of a structure but it also refers to an endless journey of a space. It is often found that the concept of originality and ageing are considered as opposite, however, in the case of Empress Market, it proved to be wrong. Although one can read the process of building aging through the change in its material and the changing functionality of the space. But one can argue that aging doesn’t justify the space losing its originality. The originality of the Empress market lies in its identity as a significant landmark in the Saddar Bazar which the heritage structure has retained to date.

The anti-encroachment drive of Empress Market

It was in 2018 when the government labelled the fruit bazaar as an encroached space and ordered the removal of them. The empress market has long survived as a fruit Bazaar, these vendors play a significant role in shaping the identity of the heritage structure. The policies of the government to retain the identity of the empress makerket and conserve it has in fact deteriorated the identity of the space. The meaning of conservation changes with each heritage structure, before being forced to take it back to its root it is important to understand the journey of the structure. Empress Market didn’t need to go back to its original identity because the local and the building dont associated itself with it, they celebrated the building with its new identity that has sustained for th 50 years; a fruit Bazaar. Thus when the conservation process began it further disrupted the identity of the heritage.

Watson Building - Mumbai, India

Esplanade Mansion, also known as the Watson Hotel, situated in a prime location of Bombay was built during 1860-1870. The structure was prefabricated in England and shipped directly to India, being the first prefabricated cast-iron structure in India. It stood alongside Gothic architecture structures in the area, foreshadowing the future of architecture construction. The edifice became a grand and vibrant emblem of British colonial power in the country until John Watson’s death and the emergence of the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel in Colaba. The building was partitioned into 150+ residences and commercial spaces after the hotel closed in the 1960s. Tenancy restrictions have made it more difficult for the owner to collect rents required to maintain the building in recent years. The cast-iron structure is in a dilapidated state.

About the Authors

About the Author

Aqsa is an under graduate student at Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture, and a self-taught writer. With keen interest in urban planning and cartography. She believes that words are the fourth or the unseen dimension of a space that can enable people to connect to spaces more than ever thus aiming to empower the architecture community through her voice.

About the Author

Urvi Basu is an architect from Mumbai who has graduated from Ctes college of architecture, Mumbai University in the year 2020. She has gained experience in designing hospital, hospitality and residential projects from project management and architectutral design firms. As the global community realizes the sparks of an irreversible climate, she wants to be proactive in the processes of improving the built environment with appropriate solutions and innovative processes to provide sensitive designs. Her area of interest lies in learning about integrating design with a futuristic approach to development that can mitigate impacts through conscious urbanism in inter-scalar forms.

Related articles

Anne Hidalgo – aris Transformation & Pedestrian Policy

What is Polycentric urbanism?

UDL Illustrator

Masterclass

Visualising Urban and Architecture Diagrams

Session Dates

28th-29th March 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “