Right to the City and the 3/30/300 Rule: Building Inclusive and Biophilic Urban Futures

This article discusses the theoretical and practical intersections of the Right to the City: a concept pioneered by Henri Lefebvre emphasizing equitable citizen control over urban space and the 3/30/300 rule, a measurable guideline ensuring access to urban trees and green spaces.

By embedding ecological justice within social justice, the narrative advances the idea that greenery is a democratic right essential for health, inclusion, and climate resilience. It presents the 3/30/300 rule developed by urban forester Cecil Konijnendijk, which sets clear benchmarks for tree visibility, canopy coverage, and proximity to green space.

The article explores Konijnendijk’s philosophy situating green infrastructure as vital for community wellbeing and democracy. It highlights practical strategies, health benefits of urban greenery, the role of community participation in greening initiatives, and the growing global adoption of the rule amid challenges like equitable distribution and green gentrification. Ultimately, it affirms the potential of combining political theory and practical design to shape just, biophilic urban futures.

Right to the City: Theory and Urban Justice

The Right to the City, a concept developed by French philosopher Henri Lefebvre in 1968, asserts citizens’ collective power to shape urban spaces to reflect their social, cultural, and political needs. Moving beyond legalistic interpretations, it foregrounds questions of accessibility, equity, and inclusion in the urban environment.

Lefebvre critiqued how capitalist urbanization commodified cities, displacing communities and limiting democratic participation. The Right to the City demands transforming urban space into a collective resource governed by its inhabitants, emphasizing social justice over market forces. In contemporary urbanism, it challenges planners and policymakers to rethink who benefits from city life and how urban space can be reclaimed as a “meeting place” for collective life.

Against this theoretical backdrop, the pragmatic 3/30/300 rule has emerged as a tool translating these abstract ideals into evidence-based design principles, linking social claims for just cities with concrete, measurable environmental standards. This synergy enriches discourse on urban inclusion by highlighting greenery as both a right and a necessity.

Ecological Justice and Inclusion in Urban Contexts

Connecting urban rights with ecological wellbeing reveals the inseparability of social and environmental justice.

Rapid urban densification and ecological degradation disproportionately affect marginalized communities, who often suffer limited access to quality green spaces. Ecological justice demands that access to shade, trees, and biodiversity be recognized not as luxury amenities but core to urban equity. By framing nature access within the Right to the City, cities reaffirm that biophilic environments contribute to health, cultural identity, and climate resilience for all citizens.

This perspective expands justice to include the natural world as a shared urban asset, requiring inclusive planning approaches that prioritize vulnerable neighborhoods. Elevating ecological justice within urban rights discourse ensures that green infrastructure investments advance equitable access, bridging social divides while fostering sustainable urban futures.

Source: Website Link

The 3/30/300 Rule

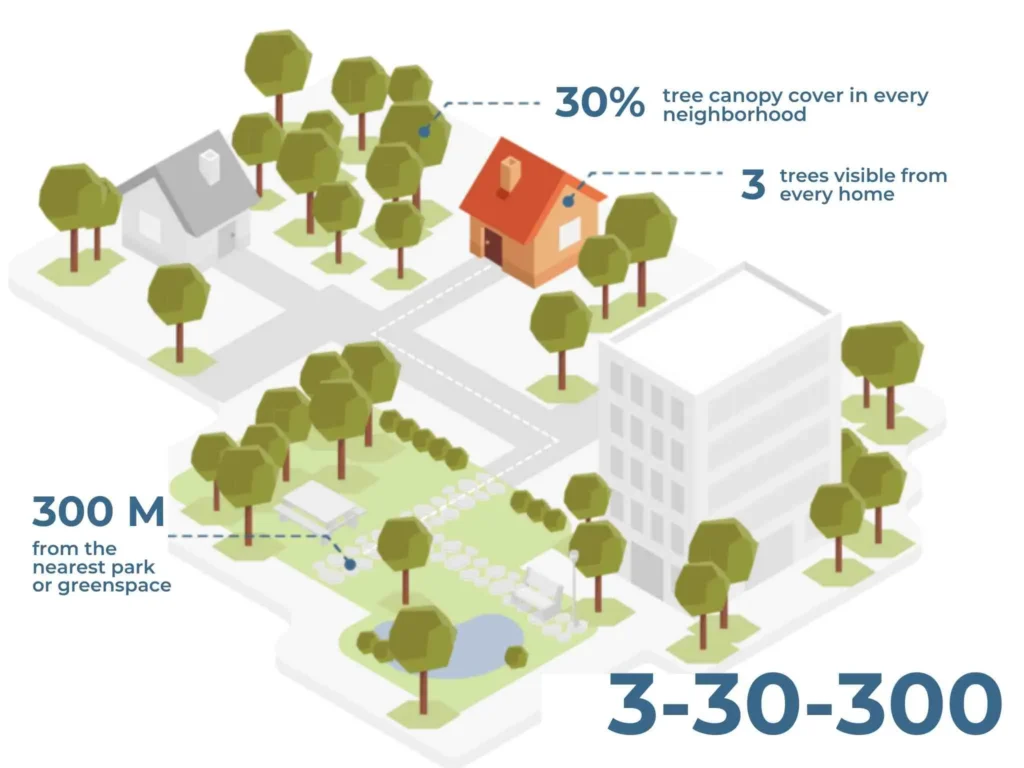

Proposed by urban forester Cecil Konijnendijk, the 3/30/300 rule sets simple yet ambitious accessibility benchmarks to urban greenery: each person should be able to see at least three mature trees from their home, reside within a neighborhood featuring 30 percent tree canopy cover, and live no more than 300 meters from a high-quality public green space of at least half a hectare.

Its power lies in its measurability and universality, providing cities with a clear framework to monitor and enhance green accessibility inclusively. This rule aids municipalities and communities in advocating minimum standards for tree presence and proximity, which confer health, social, and environmental benefits.

As a policy tool, it bridges the gap between abstract commitments to sustainability and actionable urban forestry goals, fostering cityscapes where greenery is an accessible right rather than a patchy privilege.

Cecil Konijnendijk and his Landscape Urbanism philosophy

Cecil Konijnendijk’s work situates urban forestry within the broader tradition of landscape urbanism and ecological design, viewing greenery as critical infrastructure for health, community wellbeing, and democracy rather than mere decoration.

His advocacy highlights that equitable distribution of urban trees addresses both climate adaptation and social disparities, particularly benefiting marginalized populations often deprived of greenery’s advantages. The 3/30/300 rule embodies a philosophy that integrates nature into everyday urban experience, reshaping planning priorities to ensure ecological benefits support public health and social inclusion.

Konijnendijk’s focus extends beyond technical criteria to a deeper vision of urban nature as a shared democratic resource, essential to building resilient and just cities.

Practical Design and Planning Strategies

The 3/30/300 rule informs diverse urban greening initiatives, including municipal tree-planting programs, schoolyard greening, and redevelopment projects employing its guidelines to optimize green access. By quantifying green space provision, the rule facilitates transparent target setting and community advocacy, enabling residents to engage in shaping their neighborhoods. This rule catalyzes a participatory planning paradigm where policymakers and citizens co-design equitable biophilic spaces.

Practical measures might include establishing neighborhood canopy quotas, integrating green corridors, and enhancing pocket parks within walking distance of homes. Such strategies translate social justice ideals into tangible urban improvements, bridging policy frameworks with residents’ lived experiences and fostering inclusive urban ecosystems.

Health and Psychological Benefits of Urban Greenery

Scientific research substantiates that consistent access to urban greenery delivers profound mental and physical health benefits.

Exposure to trees and parks reduces stress biomarkers, lowers cardiovascular risks, and improves cognitive performance. Green environments foster psychological relaxation, encourage physical activity, and mitigate urban heat effects, enhancing overall wellbeing. These health advantages particularly support vulnerable urban populations who disproportionately face environmental stressors.

Aligning these findings with Lefebvre’s Right to the City strengthens the argument that greenery access transcends aesthetic preference to become a fundamental urban equity issue. Ensuring democratic availability of green spaces is essential to achieving healthier, more resilient cities where all residents thrive.

Community Participation and Co-Creation

Inclusive biophilic urban futures depend substantially on community participation and co-creation. Rather than top-down tree planting, residents increasingly lead greening initiatives, stewardship programs, and local advocacy efforts, embedding urban nature within social networks.

Community engagement fosters social cohesion, environmental responsibility, and project sustainability by empowering people to shape their environments. Participatory processes align with the Right to the City by recognizing citizen agency in reclaiming urban space.

Models such as community land trusts, participatory budgeting for green spaces, and citizen science deepen resident involvement and ownership, ensuring greening initiatives reflect local needs and amplify marginalized voices. Such grassroots action is crucial for realizing equitable, vibrant, and accessible urban ecologies.

Current Situation and Global Adoption

Since its introduction, the 3/30/300 rule has begun shaping urban forestry policies worldwide. Municipalities across Europe and North America have integrated it into their greening strategies, with Latin American and Asian cities adopting analogous benchmarks tailored to their contexts.

Despite growing acceptance, challenges remain in overcoming disparities that concentrate greenery in affluent neighborhoods, risking green gentrification and displacement. Issues around data collection precision, maintenance funding, and long-term stewardship also persist. Debates continue on balancing ecological restoration with equitable distribution to ensure all urban inhabitants receive the benefits of greenery.

These ongoing conversations underscore the necessity of combining normative frameworks like the Right to the City with measurable tools such as the 3/30/300 rule for effective, inclusive urban greening.

-1

Conclusion

The Right to the City establishes a normative foundation for envisioning just, inclusive urban futures, centered on citizen empowerment and equitable access to urban resources. The 3/30/300 rule operationalizes these ideals by providing a clear, actionable framework to guarantee access to greenery essential for health, wellbeing, and social equity.

Together, they exemplify how theory and practice converge to challenge exclusionary urbanism and embed ecological justice within city planning. Recognizing urban greenery not as cosmetic but as an indispensable shared right reshapes policy and design priorities.

Embracing such integrative frameworks offers a transformative pathway to create cities that sustain both people and the planet, fulfilling democratic promises of inclusion and resilience.

References

Lefebvre, H. (1996). Writings on cities (E. Kofman & E. Lebas, Trans.). Blackwell. (Original work published 1968)

Harvey, D. (2008). The right to the city. New Left Review, 53, 23–40.

Konijnendijk, C. (2021). The 3-30-300 rule: A simple prescription for a healthier and greener city. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 59, 126978.

Konijnendijk, C. (2018). Urban forestry: Connecting people with green infrastructure. Nature-based Solutions Journal, 4(1), 15–24.

Kabisch, N., Korn, H., Stadler, J., & Bonn, A. (2016). Nature-based solutions to climate change mitigation and adaptation in urban areas: Perspectives on indicators, knowledge gaps, barriers, and opportunities for action. Ecological Indicators, 71, 123–139.

WHO Regional Office for Europe. (2016). Urban green spaces and health: A review of evidence. World Health Organization.

Wolf, K. L. (2020). Urban trees and human health: Evidence and value for ecosystem services. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 56, 126856.

Byrne, J., Wolch, J., & Zhang, J. (2009). Planning for environmental justice in an urban national park. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 52(3), 365–392.

Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224.

Gould, K. A., & Lewis, T. L. (2017). Green gentrification: Urban sustainability and the struggle for environmental justice. Routledge.

Isabella Pettengill

About the Author

Isabella Pettengill is a final-year Architecture and Urbanism student at the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS), Brazil. Throughout her academic journey, she has pursued diverse professional experiences across residential, commercial, healthcare, and urban design projects, with a growing focus on human-centered and sustainable urbanism. Her bachelor’s thesis explores the revitalization of underutilized public spaces through artistic and inclusive design strategies.

Related articles

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “