Sector 17 Plaza, Chandigarh: Modernist Urbanism

This article explores the iconic Sector 17 Plaza in Chandigarh as a case study of modernist urbanism and post-independence city planning in India. Designed as the “heart” of the city by Le Corbusier, Sector 17 embodied progressive ideals such as pedestrian-first design, civic centrality, and architectural order. While its layout and vision remain historically significant, the plaza today faces challenges of relevance amid changing urban lifestyles, competition from malls, and rigid heritage regulations. The article examines its original intent, evolving usage patterns, and proposes adaptive strategies such as reactivating edges, enhancing public infrastructure, and fostering cultural programming to reimagine Sector 17 as a vibrant, people-centric space for the future.

Chandigarh: A Vision of Modernist Urbanism

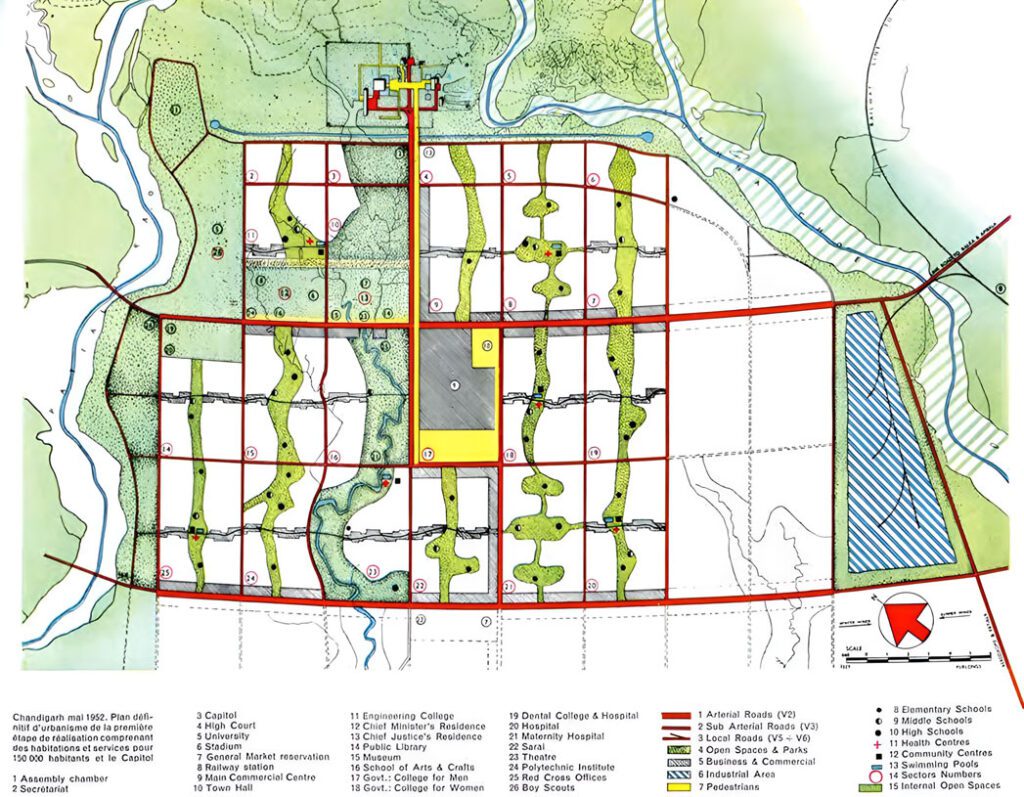

Chandigarh, India’s first planned city after independence was designed to reflect a modern, progressive national identity. Le Corbusier’s plan emphasized order, function, and harmony, guided by modernist principles. At the center of this vision is the concept of the self-contained sector, each equipped with housing, markets, schools, healthcare, and green spaces. These sectors were designed to support everyday life within walkable distances and promote community living. Public spaces played a key role in the city’s layout, reinforced by strict zoning, architectural controls, and standardized building elements to maintain a cohesive visual identity. The city was structured around a human body metaphor. The Capitol Complex was the head, the Leisure Valley and green belts formed the lungs, and Sector 17 was the heart, designed as the main civic, cultural, and commercial hub. Its central location and pedestrian-friendly design made it a true public plaza. Chandigarh is a leading example of a modernist city brought to life. Its planning shows how urban design can shape not just the physical environment, but also the social and cultural experiences of its people.

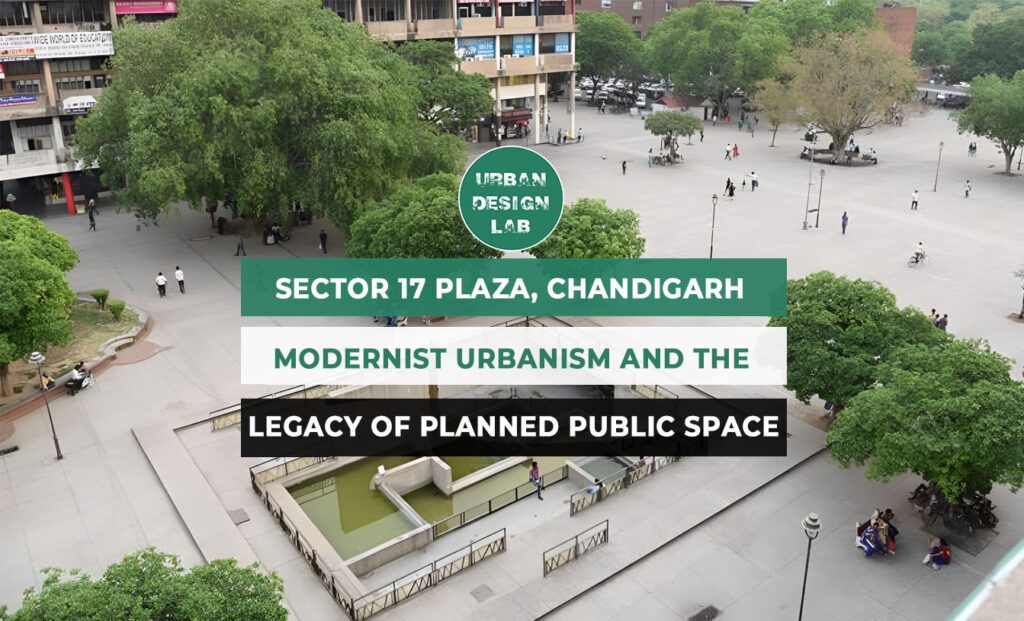

Sector 17 Plaza: The Heart of the City

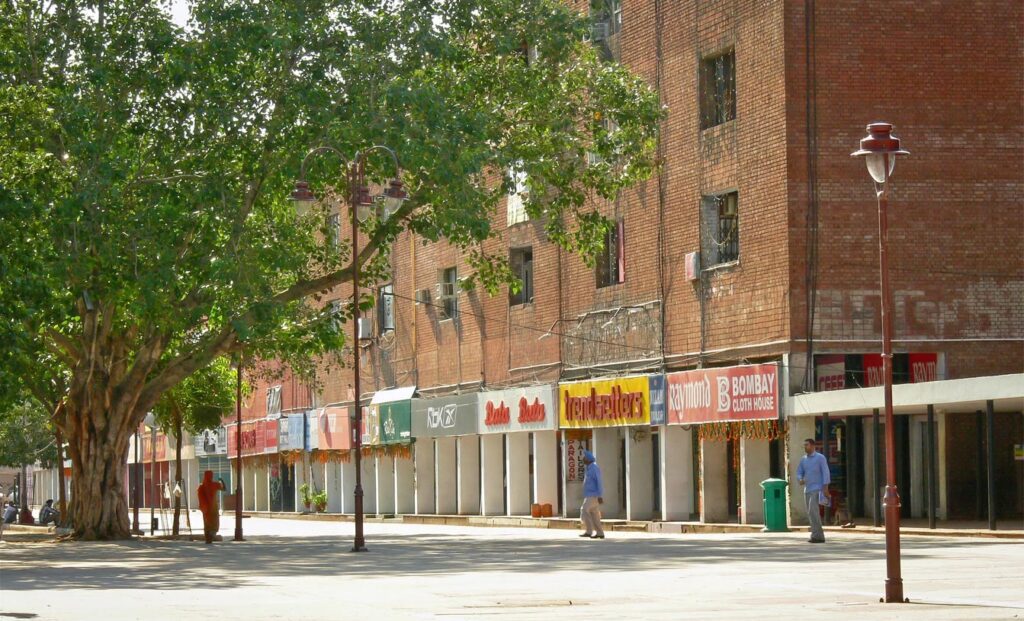

Sector 17 was conceived as the “heart” of Chandigarh, representing vitality, movement, and civic centrality. Though not geographically centered, it occupies a prime position bordered by major roadways like Jan Marg, Madhya Marg, Himalaya Marg, and Udyog Path. These arterial connections link it to key sectors and neighboring cities, underscoring its strategic role. Envisioned as the City Centre, Sector 17 was planned to integrate commerce, administration, and culture into a walkable, multi-functional urban core. Le Corbusier’s design emphasized the separation of vehicular and pedestrian flows. The plaza is structured along two intersecting axes, originally intended to feature an eleven-storey tower at their junction (never built). An overbridge allows traffic to bypass the pedestrian core. Sector 17’s layout modernized the traditional Indian bazaar into a grid of specialized market blocks, public institutions, and cultural venues.

- Key civic buildings: Town Hall, Central Library, Post and Telegraph Office, Parade Ground, District Courts, Police Headquarters

- Key commercial functions: Shopping blocks, Bank Square, Hotels, Five cinemas, Offices

- Civic and commercial zones were meant to coexist but became fragmented due to poor integration.

- The central plaza serves as a gathering space, surrounded by uniform blocks with controlled height and design.

Source: Website Link

Designing for Pedestrians: Circulation, Access, and Public Life

Sector 17 made an early and ambitious attempt to prioritize pedestrians over vehicles in Indian city planning. Cars were pushed to the periphery or elevated via overbridges, keeping the central open space free for foot traffic and civic life. This pedestrian-first strategy aimed to create a cohesive public environment, fostering interaction and accessibility. Despite this, not all parts of the plaza experienced equal success. Only one of the two intended axes near Neelam Cinema developed strong footfall, while other edges, especially near the Post Office and Police Housing, remained underused. Parking, originally designed as surface lots, failed to evolve alongside increasing motorization.

- Neelam Piazza remains the most active area due to proximity to commercial blocks and visual openness

- Other areas, especially those near the Post Office or Police Housing, experience reduced vibrancy

- Public events like Independence Day parades and open-air exhibitions continue to draw people to the plaza

- Everyday public use is limited by a lack of shade, lighting, and seating infrastructure

Today's Urban Challenges

Today, Sector 17 stands at a crossroads between heritage and modernization. As an icon of modernist urbanism, its spatial design, planning philosophy, and architectural language continue to be studied and celebrated. While its architecture and spatial logic are part of Chandigarh’s heritage, its practical relevance has diminished in the face of rising competition from enclosed, climate controlled malls like Elante and newer commercial hubs such as Sector 34. Heritage regulations aimed at preserving Sector 17’s integrity have made large-scale innovation difficult. Although efforts like plaza resurfacing, the addition of an open-air theatre, and accessibility improvements have been introduced, they remain fragmented and lack a comprehensive renewal strategy.

Reimagining Sector 17: Strategies for the Public Plaza

To remain relevant, Sector 17 must evolve from a static symbol into a dynamic, people-oriented space. Its design already includes the spatial tools for walkability, openness, and civic use, but these must now be supported by better programming, flexible uses, and targeted interventions. Future planning should focus on activating underused edges, diversifying economic activity, and integrating cultural programming into everyday life. This involves moving beyond preservation to create a more adaptable space that can host everything from daily routines to seasonal festivals and informal gatherings.

Potential Strategies:

- Adaptive reuse of underutilized blocks to include cafes, galleries, co-working, or pop-ups

- Revamped lighting, seating, and shaded areas to improve daily usability

- Public-private partnerships to co-manage and curate events

- Integration of public art, temporary installations, and smart infrastructure

Conclusion

Sector 17 Plaza remains a powerful emblem of Chandigarh’s modernist ambition, a carefully crafted space meant to embody civic life, order, and accessibility in post-independence India. Its design, rooted in Le Corbusier’s vision, showcases the ideals of planned public space and pedestrian-oriented urbanism. However, as the city evolves, so too must its public spaces. The challenge today lies not just in preserving Sector 17’s architectural legacy, but in reactivating it as a vibrant, inclusive, and adaptive civic hub. With thoughtful interventions that respect its heritage while embracing contemporary needs, Sector 17 can once again become the dynamic heart of Chandigarh’s public life.

References

- J. M., D. Chatrath, and T. Mishra, “Diagnosing Chandigarh’s Heart: The future of sector 17 as an urban public space,” International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET), Nov. 2017.

- Finance Secretary, Chandigarh Administration, “City Development Plan Chandigarh,” submitted under Jawahar Lal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM), Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India.

- Gangwar, G. Redevelopment of Central Business District Center, Sector 17, Chandigarh.

- Chandigarh Urban Planning Department, “Urban Planning,” Chandigarh Administration, Retrieved from https://urbanplanning.chd.gov.in/index.php/home/page/20

- Rodríguez-Lora, J.-A., Rosado, A., and Navas-Carrillo, D., “Le Corbusier’s Urban Planning as a Cultural Legacy. An Approach to the Case of Chandigarh,” Designs, vol. 5, no. 3, p. 44, 2021.

Tanvi Bhatia

About the author

Tanvi Bhatia is a design professional with a background in architecture, urban design and landscape planning. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in Architecture from Manipal University Jaipur, India. Passionate about creating spaces that reflect identity and purpose, her interests include inclusive urban environments, urban mobility, sustainable materials and nature-based planning, and human-centered, research-informed spatial design.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

UDL Illustrator

Masterclass

Visualising Urban and Architecture Diagrams

Session Dates

28th-29th March 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “