Seoullo 7017 Transformed from Abandoned Overpass into Thriving Green Walkway

Seoullo 7017 offers a beautiful, green path to avoid the woes of the modern city. With art installations, flowers and views of the city, it has quickly become a popular destination for tourists and locals alike. The very existence of this project, however, is indicative of the long history of autocentrism, leaving pedestrians with the ‘leftovers’ of the urban fabric. If we reframe our perspective of such projects, we can see that Seoullo 7017 offers a stepping stone, allowing relief for the pedestrian body while allowing time for more substantial overhauls to take root.

Introduction to the Project

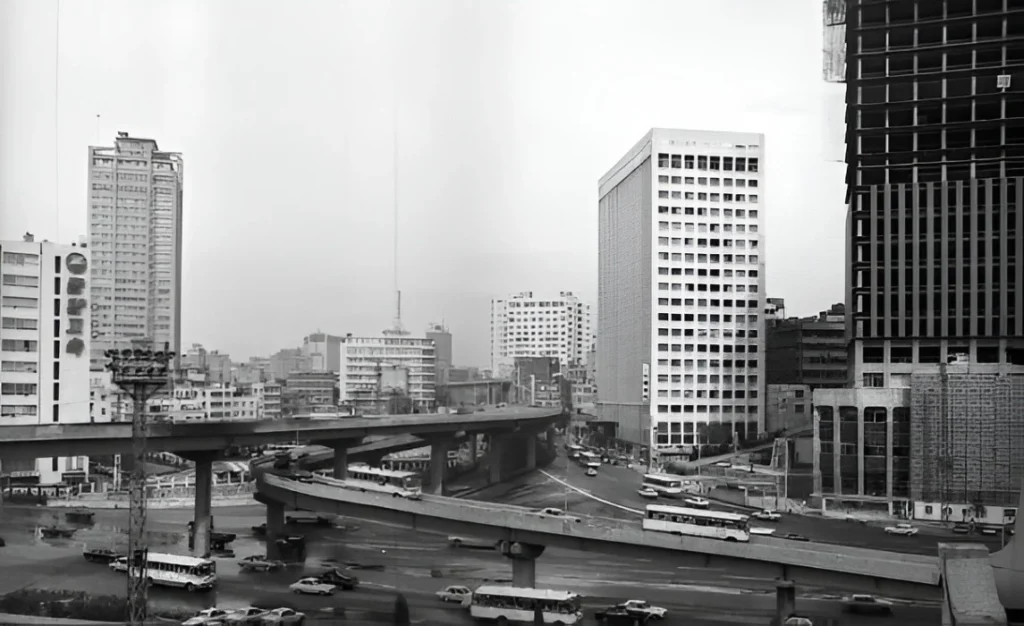

Seoullo 7017—also known as the Seoul Skygarden—is a linear park that reclaims and reprograms the former Seoul Station Overpass, a relic of South Korea’s postwar modernization era. The name “Seoullo” translates to “Seoul road,” while “7017” references the infrastructural timeline: the overpass was originally constructed in 1970 and reimagined as a public garden in 2017. This adaptive reuse project represents a strategic act of spatial recycling, transforming elevated vehicular infrastructure into an ecologically embedded pedestrian corridor.

Extending from the Mali-dong district to Hoehyeon Station, the walkway traverses a critical transit nexus above Seoul Station. The intervention has reportedly improved pedestrian permeability and connectivity in the area, reducing friction for foot traffic in a zone long dominated by car-oriented planning.

Over several hundred meters, the park functions as a curated botanical promenade, showcasing native Korean plant species across thematic clusters. It is punctuated by public amenities including cafés, kiosks, and temporary art installations, reanimating the structure not just as a transit corridor but as a multi-sensory urban experience. Its design includes 17 branching pathways, enhancing lateral accessibility to adjacent streets and neighborhoods, and facilitating porous pedestrian movement across an otherwise fragmented urban landscape.

Why is Seoullo 7017 significant?

Seoullo 7017 is emblematic of a growing global shift away from the spatial logic of mid-20th-century autocentric urbanism—an era that privileged throughput, efficiency, and infrastructural domination over human-scaled experience. As contemporary cities reckon with the ecological and social externalities of that paradigm, disused infrastructures are increasingly being reimagined not as obsolete remnants, but as latent opportunities for spatial regeneration.

In Seoul’s case, the Seoullo 7017 project reflects a conscious urban strategy of reclamation—wherein the spatial footprint of former expressways is not merely cleared, but actively reprogrammed for public life. Unlike interventions that demolish and replace, this adaptive reuse preserves the physical substrate while radically transforming its function, intent, and meaning. Here, it is not simply space that is being reclaimed—it is urban agency.

This approach finds precedent in the Cheonggyecheon restoration, where a buried stream and its surrounding highway infrastructure were dismantled to restore ecological flows and civic engagement. Seoullo 7017, by contrast, retains the elevated structure but subverts its original purpose: converting a conduit for vehicular movement into a linear ecological and social corridor elevated above the very traffic it once served.

What emerges is not just a park, but a spatial critique—an infrastructural palimpsest that embodies the tensions and transitions of post-industrial urbanism. In this sense, Seoullo 7017 functions as both a symbolic and material reclamation of the public realm, repositioning infrastructure as a site of encounter, ecology, and pedestrian sovereignty.

Source: Website Link

What Seoullo 7017 is to Seoul

While some draw comparisons between Seoullo 7017 and other elevated linear parks, notably NYC’s High Line, it is important to remember exactly what space was reclaimed. The High Line park was built on a converted viaduct belonging to the defunct New York Central Railroad. Railroads do not create traffic at their ingress/egress routes in the same way that an urban expressway might.

Seoullo 7017 reused an old highway that was built in 1970, cutting through the city nearby to Seoul Station. The reclamation now leaves auto traffic relegated to the surface, separating pedestrians and vehicles. What 7017 does well is thoughtful cleanup; cleanup from the damaging impacts of autocentricity.

Not having pedestrian access to the street surface, however, still shows that there is a social pecking order as to who has the rights to the street, the rights to the full autonomy offered by the city. Projects like Seoullo 7017 act as an interim, a quick solution while political will, funding, etc. allow for the fundamental use cases of the streets to be given back to the people.

The Right to the Streets

When looking at the implications of something like an elevated walkway, we must ask the question: why not at-grade with the rest of the street? How does this reinforce who belongs on the street?

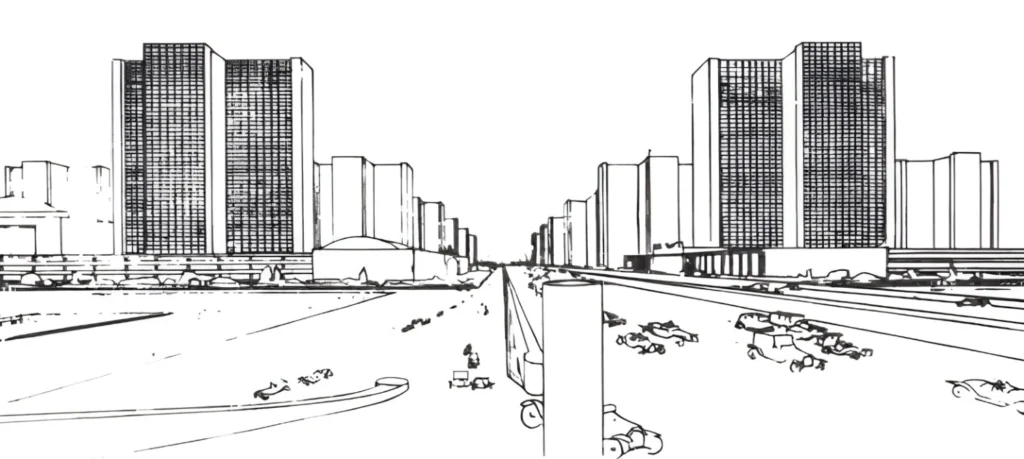

For example, Le Corbusier offered up the idea of the Ville Contemporaine and Ville Radieuse, which separated vehicle modality by speeds, primarily. The pedestrians would have most, if not all, of their services and amenities could exist within ‘vertical streets’ in the towers. Cars and rails would occupy the streets between the towers to allow for uninterrupted travel; a highway cutting through the downtown core. Australian critic Robert Hughes once said in a response to Le Corbusier’s plans, “…the car would abolish the human street, and possibly the human foot…” Whether the pedestrian avenues were raised above the street, below the surface, or between the towers, it is clear that any pedestrian convenience and autonomy would be sacrificed for the ease of the vehicles on the street.

“Temporary” Solutions to reversing auto-centricity

In a similar level of use-case segregation, we can look at the skyway or skybridge; an elevated connection between buildings.

These skyways grew in popularity in the mid-20th century, coinciding with the proliferation of the automobile age. The idea was to provide a safe, quiet alternative to the streets. The streets, which by all effective means, were intended to be wholly sacrificed to the supremacy of the automobile.

Seoullo 7017 encapsulates the echoes of this bygone era of thinking. Seoullo 7017 is a reminder of a time when the pedestrian street experience was secondary to the efficiency demanded by the automobile. What it is not, however, was built from the ground up as a skyway, but rather repurposed preexisting infrastructure.

We can think of repurposed projects like Seoullo 7017 as relief for future pedestrianization efforts. Projects like Seoullo 7017 must be built with the expectation that their existence doesn’t negate the usability of the streets below. These elevated walkways do not offer the full accessibility of the street, but allow for future projects to be created with less pressure from pedestrian traffic.

What was the pedestrian experience like before Seoullo 7017 opened?

Conclusion

Seoullo 7017 represents both a celebration and a critique of modern urban design. On one hand, it offers a reprieve from the automobile-dominated cityscape, providing pedestrians with greenery, art, and elevated views of Seoul’s urban core. On the other, it underscores the historical prioritization of vehicles over people; a leftover space reimagined for foot traffic rather than an fully-integrated reclamation of the street.

While its beauty and function are undeniable, Seoullo 7017 should not be mistaken as a complete solution to reversing autocentric planning. Instead, it should be seen as a transitional space: a creative repurposing that acknowledges the need for human-centered design while buying time for more systemic urban reforms. True pedestrian equity will only come when cities no longer require such elevated escapes from street-level congestion and danger. The ultimate goal must be to reclaim the streets themselves, not just their cast-off remnants. Until then, Seoullo 7017 serves as a symbolic and functional reminder of what is possible when we begin to reimagine infrastructure not for cars, but for communities. It is a bridge, literally and figuratively, between the cities we have and the cities we must still build.

References

- Alpert, D. (2008, February. Skybridges don’t make the connection. Greater Greater Washington. https://ggwash.org/view/219/skybridges-dont-make-the-connection

- Blewett, L., Nguyen, N. X., Makki, M., & Showkatbakhsh, M. (2023). The development of habitable urban skyways: Claiming interstitial territories through evolutionary processes. City, Territory and Architecture, 10(1).

- Heathcote, E. (2017, May 5). How architects have tried to create “streets in the sky.” Subscribe to read.

- Le Corbusier. (1929). The City of To-Morrow and Its Planning. New York: Payson & Clarke.

- M, A. (2023, August 10). Seoullo 7017 – beautiful sky garden walkway in Seoul. KoreaTravelPost. https://www.koreatravelpost.com/seoullo-7017-sky-garden-walkway-seoul/

- O’Donnell, C. (2019, June 1). Le Corbusier: From the contemporary city to the Radiant City. Urban Utopias. https://urbanutopias.net/2019/06/01/le-corbusier/

- Seoullo 7017. 서울의 공원. (2014). https://parks.seoul.go.kr/template/sub/seoullo7017.do

- Si-soo, P. (2017, April). Seoullo 7017, overpass-turned-park, to open in May – The Korea Times. koreatimes.co.kr. https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/southkorea/society/20170426/provincial-news-seoullo-7017-overpass-turned-park-to-open-in-may

- Rule, D. (2015, May). Seoul Skygarden set to rival New York’s High Line. The Sydney Morning Herald.

- Zorthian, J. (2017, June 1). Seoul’s garden in the Sky. Time. https://time.com/4800807/seouls-garden-in-the-sky/

Ethan Anderson

About the Author

Studying for his BA in Urban Studies, Ethan seeks to improve the modern urban fabric through novel implementations of both new and old ideas. Born and raised in a town that rose and fell at the hands of the now defunct railway, it has been a constant and everpresent reminder how influential the built environment is to our success as a community.

Related articles

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “