The City Remembers: Media Archives as Digital Collective Memory

In an era dominated by datafication and digital infrastructure, urban memory is no longer preserved solely in monuments, books, or oral histories. Increasingly, it is stored, accessed, and negotiated through digital media archives. These archives do not just represent the past – they shape how it is understood, by whom, and for what purpose. This article explores the idea of the city as an archive, drawing on Shannon Mattern’s critique of technocratic urbanism, and situates this in the context of the Urban Lviv Archive, a digital memory project documenting Ukraine’s wartime urban experience.

The City as an Archive

Digital archives have become a vital layer of urban memory-making, storing not only histories but also ongoing lived experiences and political transformations. These archives present opportunities to preserve collective memory, but they also demand critical reflection on their limitations, ethics, and the ways they shape social power and urban identity.

Scholars such as Roberts (2014) discuss the concept of the city as an archive – a virtual or digital space where memories, histories, and cultural artifacts of a city are stored and accessed. For Roberts, an archive city’s success depends on its ability to serve not only as a record of the past but also as a living and participatory space. Without the active involvement of citizens, these digital repositories risk becoming sterile, model-like representations of the city, detached from everyday life.

Roberts emphasizes that the effectiveness of an archive city is not measured by the quantity of materials stored, but by how people interact with it – using accessible digital tools to contribute to, navigate, and mobilize memory. In this way, digital archives become a collaborative process of ongoing memory-making, connecting individuals with urban history and identity.

From Dashboard Governance to Urban Organisms: Mattern’s Critique

In her book A City Is Not a Computer, Shannon Mattern explores metaphors that have long shaped how cities are planned and managed. In chapter one, “City Console,” she introduces the concept of “dashboard governance,” where city management increasingly relies on visual displays of key metrics to inform decision-making. While dashboards promise efficiency and clarity, Mattern warns that they often promote a technocratic, top-down governance style. This approach may reduce complex urban issues to simple data points, which risks obscuring nuance and reinforcing systemic biases.

For example, while data dashboards used during the COVID-19 pandemic provided important information, they also enabled racial profiling and overreliance on predictive models. Geographic Information Systems (GIS), too, have shown how correlation can be dangerously mistaken for causation, disproportionately affecting marginalized populations.

In chapter two, “The City is Not a Computer,” Mattern critiques the dominant metaphors of the city as a machine, operating system, or even as code. She argues that these computational framings reduce the city to something calculable, sidestepping the messy, emotional, and human aspects of urban life. Cities, she proposes, should instead be seen as organisms – fluid, evolving, and deeply rooted in memory, history, and lived experience.

Source: Website Link

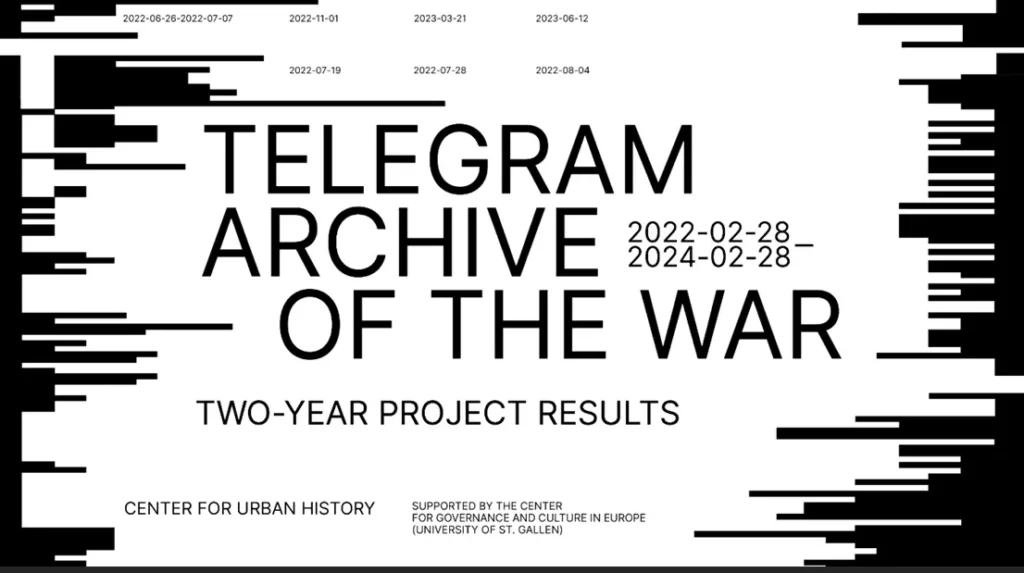

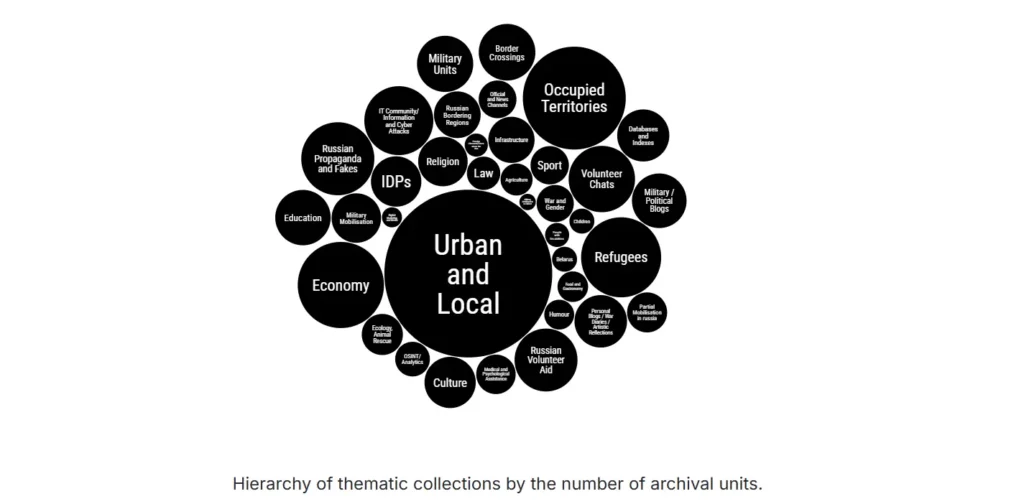

Digital Archives as Collective Memory: The Case of Urban Lviv Archive

The Urban Lviv Archive, developed by the Center for Urban History of East Central Europe, exemplifies the memory-oriented, transdisciplinary archive envisioned by Shannon Mattern. As part of its War Documentation Project, the archive collects and preserves diverse materials related to the ongoing war in Ukraine – many of which fall outside official state channels. These include oral testimonies from displaced people and volunteers, photographs, audio recordings, drawings, music, and videos. It also archives Telegram messages, which have played a vital role in coordinating evacuations, sharing shelter locations, and spreading military updates.

The archive serves multiple purposes. It empowers individuals to contribute personal perspectives, helping to resist historical erasure. It also creates a long-term record that may support future justice and governance efforts, including legal accountability. Importantly, it captures how urban life has shifted in wartime – how public spaces have been repurposed and how new survival strategies have emerged.

According to Taras Nazaruk, head of the digital history department, the goal is to build a verified, enduring source for researchers while amplifying voices often overlooked. In this way, the Lviv archive reflects Roberts’ (2014) vision of the archive as a participatory, evolving space that bridges physical and digital urban memory.

Human-Machine Intra-Actions

Digital archives are not just about collecting and storing data; they involve what some scholars call human-machine “intra-action.” As Pentazou (2023) explains, these archives are conceived as spaces that aspire to “have everything.” But that aspiration is also where their limitations lie. The act of archiving Telegram channels over many years results in vast, unwieldy collections of data. Without clear curation or purpose, the archive risks becoming cluttered, and meaning may be lost in the noise. As both Pentazou and Mattern argue, meaning doesn’t come from simply organizing information, it arises through interaction. Interpretation, reflection, and engagement are what turn collections into knowledge.

Jacques Derrida (1995) reminds us that archives don’t just preserve events; they shape them. By choosing what to include, how to categorize it, and how it’s accessed, archivists actively construct history. This makes ethical questions particularly urgent in digital archiving: What gets included? Who has access? How is sensitive information protected? Taras Nazaruk addresses these concerns directly. The Urban Lviv Archive does not publish sensitive Telegram data without consent. Instead, it prioritizes protection, long-term preservation, and future contextualization.

The Archive as Urban Praxis

In many ways, the Urban Lviv Archive reflects a broader shift in thinking about cities – not as computers or machines to be managed, but as dynamic archives co-created by residents, researchers, and digital technologies. Its goals are both scholarly and civic: to provide data for historians, offer a voice to the marginalized, and influence local governance by making urban problems visible.

Anastasiya Kholyavka, an assistant with the “City Media Archive” project, explains the stakes clearly: “The war that is being waged against us is also a war against our memory, so it is important to find ways to preserve it.”

The digital archive thus becomes a form of urban praxis – a way of knowing and shaping the city. It’s not a dashboard spitting out statistics. It’s a collective, contingent, and ethical endeavor to preserve lived experience.

Conclusion

Toward the City as an Archive

As Mattern reminds us, “City-making is city-knowing.” And knowing the city cannot be reduced to code or computation. It involves storytelling, memory, and the complex negotiation between humans and machines. The Urban Lviv Archive attempts exactly this: to create a platform where data becomes narrative, and where memory becomes a tool for justice, policy, and healing.

In contrast to dashboard governance or technocratic urbanism, this model offers a different metaphor – not the city as a computer, but the city as an archive. An archive that is alive, participatory, and built through countless interactions between people and technologies.

Digital archives, when thoughtfully curated and ethically maintained, can embody this metaphor. They become not just tools for preserving the past but instruments for shaping more inclusive, reflective urban futures.

References

- Bilousenko, O. [Білоусенко, О.]. (2022, May 20). Ми боремося за збереження пам’яті [We fight for the preservation of our memories]. ms.detector.media. https://ms.detector.media/trendi/post/29523/2022-05-20-my-boremosya-za-zberezhennya-pamyati/

- Lviv Center for Urban History. (2022, March 25). War documenting projects. https://www.lvivcenter.org/en/updates/documenting-the-war-2/

- Mattern, S. (2021). A city is not a computer: Other urban intelligences. Princeton University Press.

- O’Driscoll, M. (2002). Derrida, Foucault, and the Archiviolithics of History. After Poststructuralism: Writing the Intellectual History of Theory, 284-309.

- Pentazou, I. (2023). “Having everything, possessing nothing”: Archives and archiving in the digital era. Punctum. International Journal of Semiotics, 09(01), 133–152. https://doi.org/10.18680/hss.2023.0008

- Roberts, L. (2015). Navigating the “archive city”: Digital spatial humanities and archival film practice. Convergence, 21(1), 100–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856514567052

Maja Belostotski

About the author

Maja Belostotski holds a degree in Urban Studies from Leiden University and is currently pursuing an MSc in Redesigning the Post-Industrial City through the UNIC consortium. As a spatial researcher, her work focuses on cultural heritage, urban policy, and social planning, with an interest in Central and Eastern Europe. Passionate about the narratives embedded in urban spaces, she explores how cities preserve their essence through adaptive reuse. Her research is also concerned with post-conflict resilience, seeking out the textures of places that help communities rebuild, reconnect, and reimagine their futures.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “