The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces: Reviving Jane Jacobs’ Legacy

In the ever-expanding grid of cities, it’s often the smallest corners that leave the deepest imprint on our daily lives — a shaded bench under a tree, a stoop with chatter, or a corner café buzzing with life. Urbanist Jane Jacobs once said, “Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.” Today, as our urban spaces grow denser and taller, it becomes all the more vital to look downward — at the streets, sidewalks, and little pockets of pause that keep city life human. This article dives into how small urban spaces are not just surviving, but reviving, and why Jane Jacobs’ lens is more relevant now than ever.

Jane Jacobs and the Power of the “Sidewalk Ballet”

In the 1960s, Jane Jacobs challenged conventional city planning by focusing not on buildings, but on people — and the way they interact. Her concept of the “sidewalk ballet” captures the spontaneous, layered interactions that make neighborhoods feel alive. A street vendor waves to a school kid. A neighbor chats with another while watering plants. These aren’t grand gestures, but micro-interactions that stitch the social fabric. Today, as cities become more data-driven and automated, we’re in danger of losing this slow choreography. Reclaiming Jacobs’ vision is about reactivating streets with life, not just traffic.

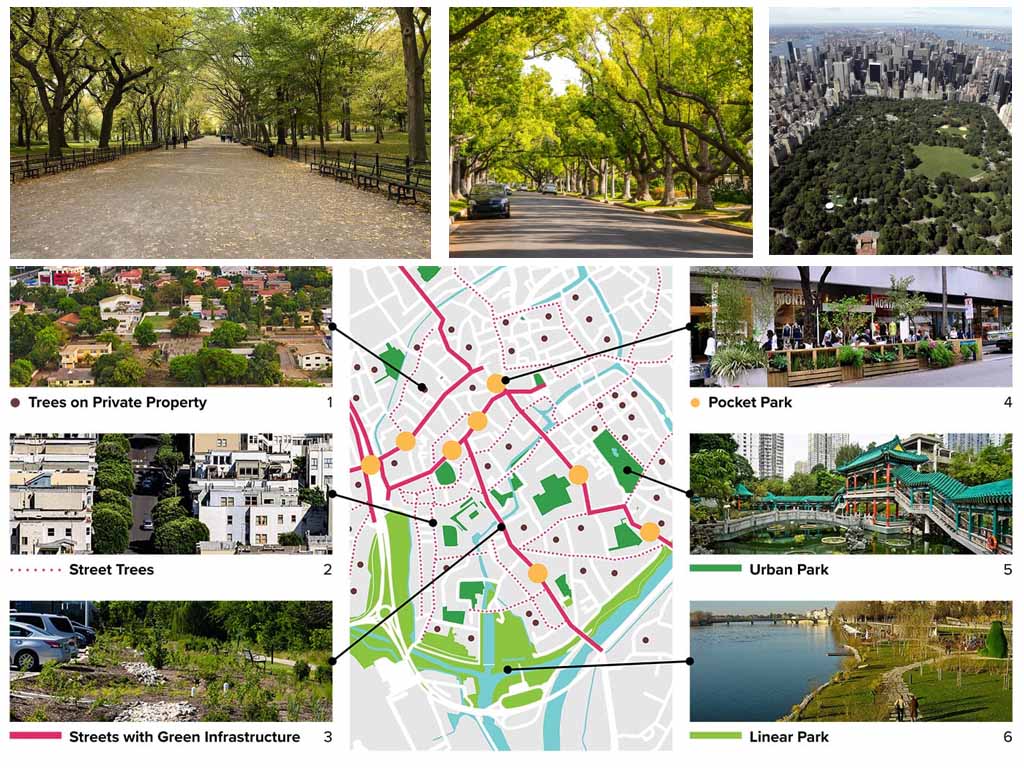

The Forgotten Value of Small Urban Spaces

Think of your favorite urban memory — chances are, it didn’t unfold in a giant plaza or glossy mall. It happened in a shaded corner of a park, at a street crossing with buskers, or outside a bookstore on a quiet lane. These “in-between” spaces — pocket parks, stoops, courtyards, alleys — often get overlooked in planning documents, yet they’re the heartbeat of community life. William H. Whyte, whose work echoes Jacobs’, emphasized the importance of sittable space, movable chairs, and people-watching. These spaces, while small in scale, are enormous in social impact.

Source: Website Link

Observing the Human Pulse of a City

During an urban study in Chennai’s Egmore or a walk through Fort Kochi’s heritage streets, it becomes obvious how much small design decisions influence behavior. Where there’s a step to sit, people pause. Where there’s shade, they gather. Where there’s visibility, they feel safe. Designers and architects must become observers first — seeing how people use spaces rather than how we imagine them to function. This shift from prescription to participation is what Jacobs championed. It’s not about designing for people; it’s about designing with them.

Contemporary Lessons in Creating Socially Vibrant Spaces

Across the world, cities are reviving Jacobs’ ideas in new formats. New York’s Bryant Park turned from a neglected space into a community hub through movable chairs, food kiosks, and performances. In India, efforts like the Tender SURE streets in Bengaluru and tactical urbanism in Pune showcase how even temporary, low-cost interventions — like painted crossings, planter boxes, and pop-up seating — can reshape street dynamics. These changes may be modest, but their impact on walkability, safety, and vibrancy is profound. Small is not just beautiful — it’s powerful.

Designing with Empathy, Not Ego

The future of urban design lies in humility — in understanding that architects and planners are not just creators, but facilitators of social life. The grandeur of skyline-changing architecture will always be celebrated, but the soul of a city lives in how it feels at eye level. When we create with empathy — noticing where people seek shade, where they pause, how they connect — we move toward cities that breathe, not just function. Jacobs’ work isn’t nostalgia; it’s a challenge to return to the core of city-making: human life.

Conclusion

Reviving Jane Jacobs’ legacy means more than citing her words — it means truly seeing our cities through her eyes. Eyes that noticed the unnoticed, believed in messy spontaneity, and fought for everyday people’s right to shape their space. In our race toward smart cities and vertical skylines, let’s not forget the sidewalk stories — the laughter, the lingering, the lives unfolding in small corners. Because in the end, it’s not the megastructures, but the moments in-between, that make a city lovable.

References

- https://streetlifestudies.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/1980_whyte_small_spaces_book.pdf

- https://archive.org/details/sociallifeofsmal0000whyt

- https://archive.org/details/CitySpacesHumanPlaces

- https://www.petkovstudio.com/bg/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/The-Death-and-Life-of-Great-American-Cities_Jane-Jacobs-Complete-book.pdf

- https://ijissh.org/storage/Volume4/Issue11/IJISSH-041101.pdf

Devyani Prasad

About the Author

Devyani Prasad is an undergraduate architecture student passionate about sustainable, vernacular, and culturally rooted design. Her work blends research, design thinking, and practical imagination to create meaningful, functional spaces. She explores the intersection of tradition and innovation, with a deep respect for local materials and cultural context. Devyani’s academic journey is guided by the belief that architecture can be a powerful tool for societal impact. She has also contributed to architectural discourse through research and writing, reflecting her commitment to thoughtful, context-driven design.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

Top 7 Landscape Architecture Firms in Brazil You Should Know

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “

One Comment

Nice one💯💯