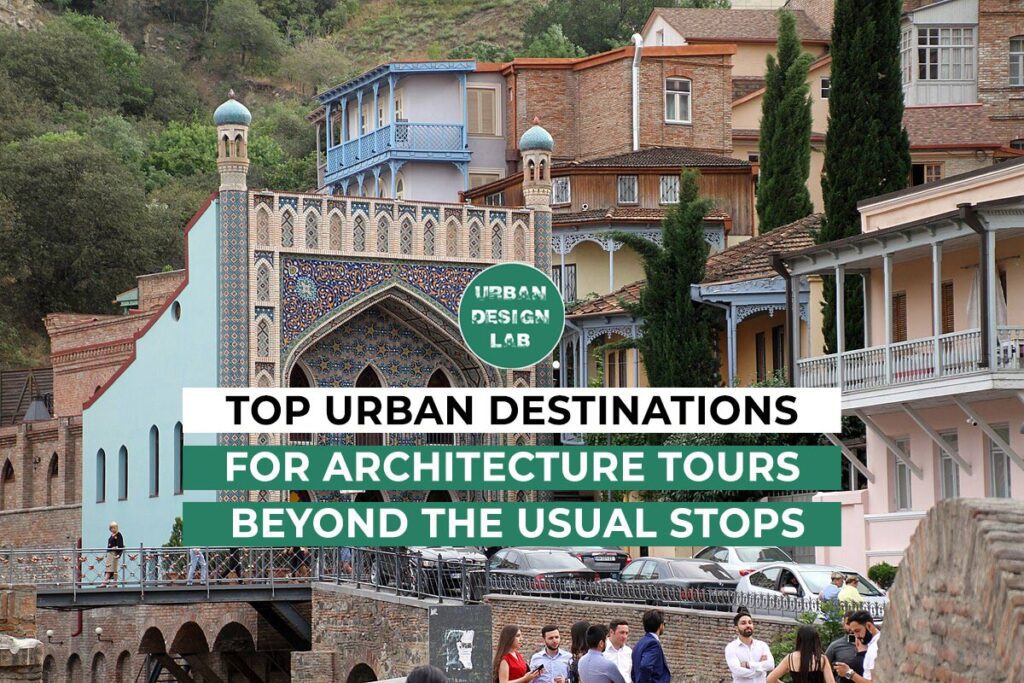

Top Urban Destinations for Architecture Tours Beyond the Usual Stops

In a time when climate resilience, cultural preservation, and sustainable design are shaping the future of urban living, architecture tours are evolving. They are no longer limited to the famous skylines of New York, Paris, or Rome. This article explores ten cities around the world with innovative and meaningful architecture. From Bandung’s modernist legacy shaped by its colonial past to Freiburg’s community-led sustainability, these places show how architecture tells layered stories of history, innovation, and future readiness.

Each city comes from a different part of the world, Asia, Europe, Latin America, and Oceania and carries a story shaped by its geography, politics, and people. Singapore’s vertical greenery, Medellín’s social infrastructure, and Valparaíso’s informal urbanism demonstrate how design can be rooted in both ecology and equity. The article draws from real-world examples to emphasize that passive housing, adaptive reuse, public participation, and resilient landscapes are vital to contemporary architecture. These destinations urge architects, planners, and culturally curious travelers to rethink how they explore cities. Rather than chasing iconic landmarks, they invite us to experience how cities live, breathe, and adapt.

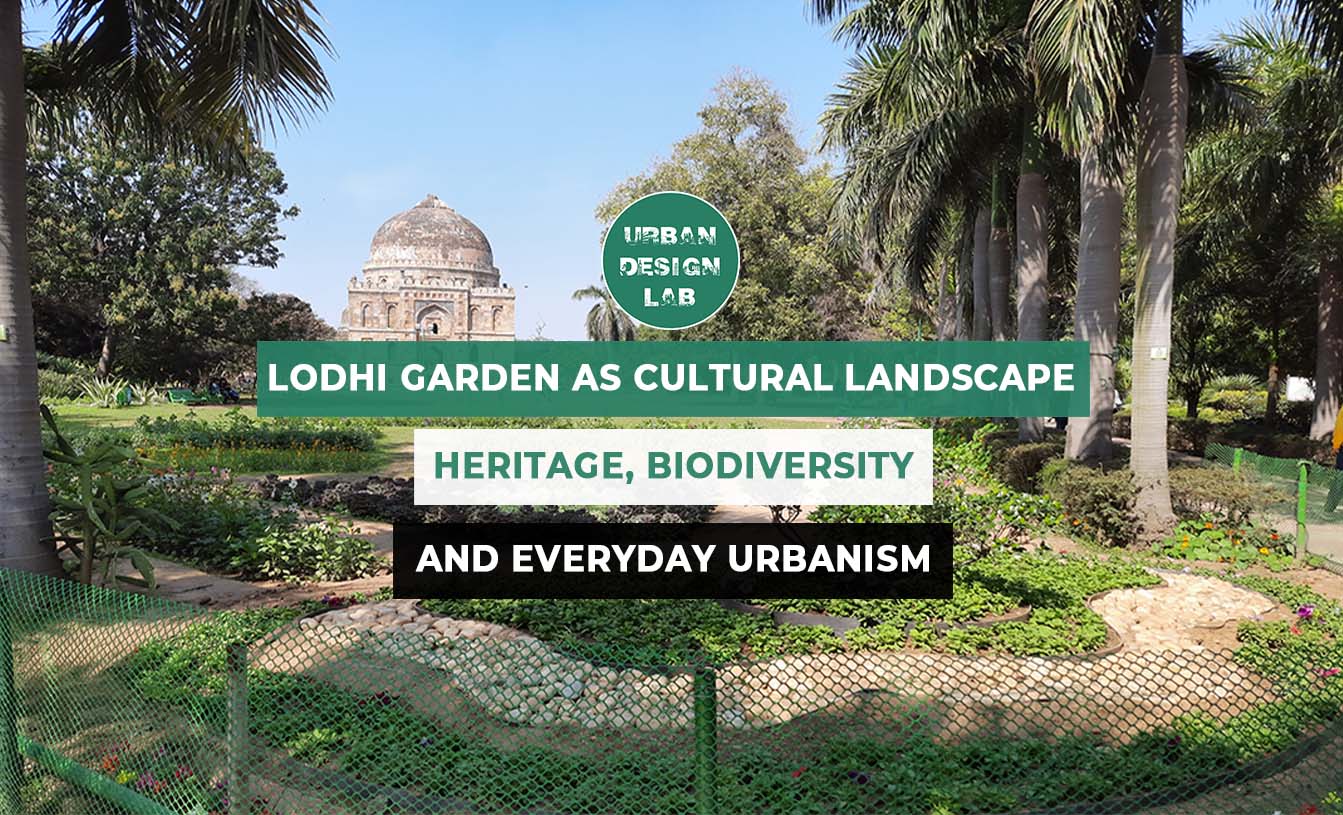

Tbilisi, Georgia: Merging Intangible Heritage with Contemporary Urbanism

Tbilisi’s buildings show the story of a city that is always changing to be more sustainable and eco-friendly. From medieval churches and wooden balconies in Old Tbilisi to Soviet-era Brutalist monuments and sleek new government buildings, the city’s architecture is a mix of styles that fit together surprisingly well. One of the most famous structures, the Bridge of Peace, shows this combination by connecting old areas with new buildings. At the same time, researchers are studying traditional Meskhetian terrace agriculture. They want to know if it can be used in city landscaping. This type of agriculture is good at keeping water and stopping it from eroding the land. The Giorgi Chitaia Open-Air Museum preserves a variety of traditional styles that influence local eco-design practices. As Tbilisi invests in public transportation that causes less pollution and solutions that make city life easier, it also remains connected to its architectural roots. Green roofs and renovated public courtyards now enhance older buildings in adaptive reuse projects. The city combines its historic sites and buildings with modern green spaces. This makes it an excellent example of an urban area that is ready for the future while also respecting its history.

Rotterdam, Netherlands: Designing for Water, Waste, and Climate Resilience

Rotterdam shows how architecture can deal with environmental problems by using smart designs. Rotterdam is a city built mostly below sea level. This makes it vulnerable to rising sea levels and extreme weather caused by climate change. Instead of retreating, it has used climate threats as opportunities to create new urban areas. Initiatives like the Recycled Park turn plastic waste into floating ecological platforms. These platforms add biodiversity and educational value to the riverfront. Water plazas, like Benthemplein, are places that serve many purposes. They are used for sports and as places to collect rainwater. Green rooftops and permeable streets help the city absorb rainwater. In addition, the transformation of former industrial docks into green, mixed-use communities shows a circular approach to space and materials. The city’s resilience is not just a technical feature, but also a beautiful addition to the city’s public spaces that engages and inspires residents. The city is also working on urban farms, bicycle infrastructure, and interactive public art. Rotterdam is an living lab that teaches how to make buildings that are both beautiful and adaptable to the climate.

Source: Website Link

Bandung, Indonesia: From Colonial Lab to Eco-Urban Showcase

Bandung has long been admired for its beautiful architecture. The city was once called “the nation’s laboratory of colonial architecture.” It is home to heritage buildings from the Dutch East Indies period, such as Gedung Sate, Villa Isola, and the Art Deco-style Savoy Homann Hotel. These buildings show how Bandung has changed over time and continue to attract scholars and tourists. Beyond its colonial past, Bandung has become a hub for experimenting with environmental and design ideas. The Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB) develops new ways to build sustainably, including passive cooling, natural lighting, and bamboo construction. The city is also working to be more eco-friendly. For example, it has renovated the once-polluted Cikapundung River into a public green space. Urban farming, rooftop gardens, and community-led housing improve resilience and livability. Local governments support pilot projects using porous paving, green alleys, and low-impact development. Bandung’s buildings reflect a blend of history and forward-thinking urbanism, showing how tropical cities can innovate by staying true to local identity and encouraging collaboration.

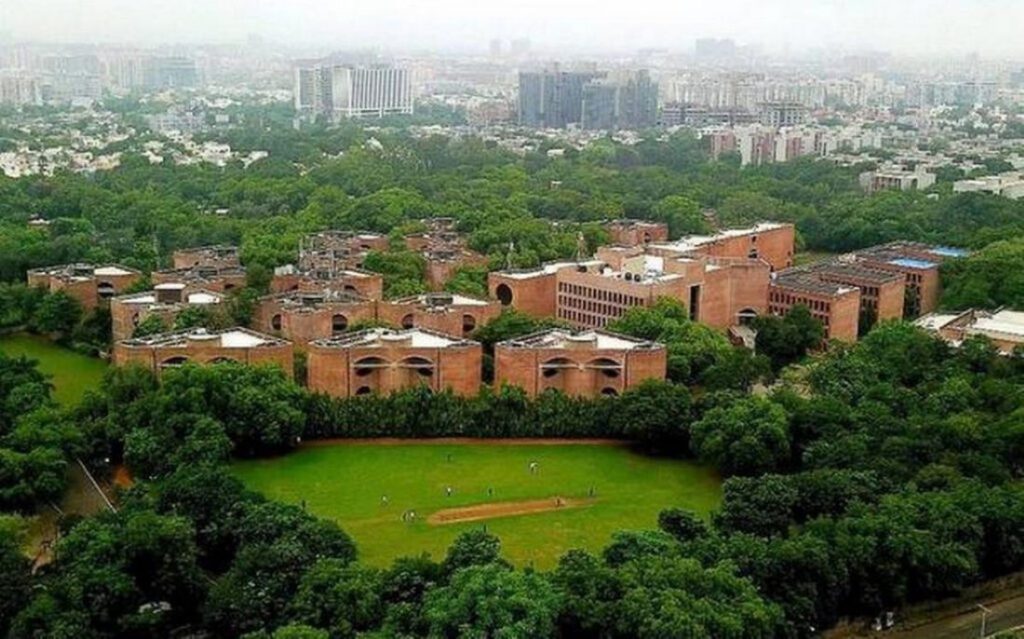

Ahmedabad, India: Modernist Icons Anchored in Climate-Responsive Design

Ahmedabad is a city that combines its rich history, modern buildings, and sustainable design. It is famous for being the Indian city where Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn left lasting architectural marks. It also has centuries-old public neighborhoods that show passive design, which was not written down until much later. These compact, inward-facing housing groups use narrow lanes, shaded walls, and inner courtyards to control heat in a harsh climate. The city’s modern architecture follows this tradition by using buildings and designs that use less energy and materials. Institutions like CEPT University encourage this. People are increasingly reusing old colonial and industrial buildings. They use these buildings as galleries, offices, and schools. Ahmedabad also has plans to include green corridors, rainwater harvesting, and more trees in the city. Public plazas are now places where people come together and where nature can thrive. The combination of modern design experiments and traditional adaptations in this city shows how a city can bring together global design discussions and local sustainability practices. If you’re someone who’s interested in architecture, you’ll love Ahmedabad. You’ll see iconic structures and learn how tradition inspires innovation.

Kyoto, Japan: Cultural Continuity Through Ecological Design

Kyoto shows how traditional architecture and environmental ethics can come together to create designs that last and are good for the environment. The city’s traditional townhouses, shrines, and temples show how Japanese design has evolved over many centuries. The thick walls, sliding screens, and deep eaves naturally control the temperature and amount of light, making them well-suited to Kyoto’s seasonal climate. Green spaces, like small gardens and temple forests, have spiritual and environmental benefits, increasing biodiversity in cities. In modern Kyoto, these traditions still influence new buildings. Timber-framed offices and low-rise housing developments follow height and scale rules that keep them in harmony with the historic skyline. City planners use zoning to encourage streets that are friendly to people and easy to walk on. The city also invests in technologies and materials that use less energy and are made in the local area. In Kyoto, sustainability is not just a passing trend, it’s a way of life that has been passed down through generations. Kyoto has been a model for other cities that want to balance progress and preservation.

Freiburg, Germany: Europe's Greenest City by Design

Freiburg im Breisgau has long been praised as a model of environmentally friendly urban planning. Located at the edge of Germany’s Black Forest, this university town integrates architecture, mobility, and energy efficiency with community well-being. The Vauban district exemplifies sustainable neighborhood design. Built on a former military base, it features solar-powered homes, green roofs, car-free streets, and district-wide renewable energy systems. Architects and planners worldwide visit Freiburg to learn how to create vibrant, high-quality living spaces that are also ecological. Freiburg also leads in public infrastructure. The Freiburg Town Hall is the world’s first public building to produce more energy than it consumes, using solar panels and geothermal systems. The city prioritizes walking, biking, and public transport over cars, improving air quality and accessibility. Impressively, these transformations are community-driven. Residents participate in planning, helping shape building codes, renewable energy goals, and design standards. Freiburg proves that sustainable cities are not just technical successes, they are social ones too. Its architectural evolution demonstrates how ecological innovation and civic engagement can shape inclusive, resilient urban futures.

Singapore: Vertical Urbanism and Green Integration

Singapore has become a global leader in sustainability. This happened quickly, and it is clear that the country has a vision for its future. The city-state was the first to create vertical greenery with buildings like the Oasia Hotel Downtown and Marina One, which are living ecosystems. These structures add shade, air circulation, and native plants to building exteriors and rooftops, which reduces energy use and increases biodiversity. The government enforces strict Green Mark standards that promote water efficiency, low-carbon materials, and biophilic design. Singapore’s master planning includes more than just buildings. It also includes urban farming zones, park connectors, and infrastructure that can handle stormwater. One example is the Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park, where a concrete canal was transformed into a naturalized river. Public housing includes sky gardens and shared courtyards, making sustainable living possible for many people. Singapore has created a model for other tropical cities to follow. The model combines policy, technology, and design. It shows how cities can grow their economies while also protecting the environment.

Medellín, Colombia: Architecture as a Tool for Social and Environmental Inclusion

Medellín used to be known for its conflict, but it has changed. It is now an example of inclusive, sustainable urbanism where architecture helps create equal opportunities. The change started with “social urbanism,” an approach that puts public infrastructure in neighborhoods that don’t have a lot of resources to help people connect and feel dignified. Notable projects include Library Parks, which combine libraries, gardens, and cultural venues, offering education, green space, and safety in areas that were previously stigmatized. The Metrocable gondola system connects remote barrios (neighborhoods) with the city center, making it easier to get around and reducing pollution. Public escalators and pedestrian bridges are more than just ways to get around. They also represent an open invitation to everyone. Many public spaces are also used as ecological zones. These spaces include green roofs, bioswales, and native vegetation. Medellín’s design ideas are based on working together. Architects, officials, and residents work together to create spaces that meet social needs and respect the environment. It shows how thoughtful design can rebuild both landscapes and livelihoods.

Wellington, New Zealand: Building with Seismic Resilience and Green Principles

Wellington, New Zealand’s capital, is a city where the risk of earthquakes and sustainable design meet. It was built on fault lines, so it has become a testing ground for strong architecture that is also environmentally conscious. Structures like the Wellington Central Library and the Te Papa Tongarewa museum use base isolation and flexible materials to withstand earthquakes while maintaining inviting, public-facing designs. New housing projects use solar orientation, high insulation, and water collection systems. The city’s plan for the waterfront includes mixed-use zoning, making it easy for people to walk there, and restoring the area’s natural plants. To deal with rising sea levels, we’re starting to use special designs like raised pathways and green stormwater infrastructure. Wellington’s public policies support a low-carbon vision. This includes promoting mass transit, building bike infrastructure, and energy-efficient building codes. The city shows how being resilient doesn’t mean neglecting community involvement or the quality of design. Instead, it can encourage new ideas.

Valparaíso, Chile: Layered Urbanism and the Aesthetics of Informality

Valparaíso is a city where buildings don’t follow the usual rules of architecture, and the shape of the land influences how the city looks. Located on steep hillsides above the Pacific Ocean, its colorful homes, murals, and staircases have earned it UNESCO World Heritage status. But beyond the pretty pictures is a deeper story of resilience and ingenuity. The city’s informal neighborhoods, many built by residents without formal plans, show how people can adapt architecture to fit social and environmental needs. These responses, small layouts, multifunctional terraces, and reused buildings demonstrate surprising climate adaptability. Architects and planners are now using these ideas to improve public housing. Valparaíso is also investing in disaster-resilient infrastructure, especially against landslides and wildfires, by adding green spaces and erosion-resistant landscaping. Local initiatives promote rainwater harvesting, energy-efficient retrofits, and public art, turning neglected areas into valuable community spaces. Valparaíso stands out by honestly reflecting its layered architectural identity. It shows that beauty can arise from necessity, and that sustainability must embrace cultural diversity. For architecture lovers, the city offers not only visual richness but also lessons in organic urban design, collaboration, and community strength.

Conclusion

The cities discussed in this article show that the most rewarding architectural tours aren’t always found in the well-known global capitals. Instead, they exist in places where design serves as both cultural dialogue and climate response. From Wellington’s earthquake-resistant waterfront to Ahmedabad’s climate-conscious courtyards, these cities show that architecture can be both beautiful and functional. Each destination offers something special: a blend of history and innovation, a commitment to environmental sustainability rooted in local knowledge, and a focus on making communities central to planning. They prove that good design isn’t reserved for wealthy or famous cities. Instead, they celebrate creativity born from constraint and collaboration.

These cities don’t just have great buildings, they demonstrate resilience, adaptability, and inclusivity. For those seeking architecture tours that go deeper, ask meaningful questions, and give voice to local communities, these ten destinations are a powerful place to begin. As we move through these spaces, we engage with architecture not as passive observers, but as active learners. We witness how cities breathe, remember, and prepare—and discover that the most compelling architectural stories often lie in the places least expected.

References

- Everts, E. (2021). Water-sensitive urban design in Rotterdam: Strategies for flood resilience. Urban Climate, 36, 100762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2021.100762

- González, S., & Mukhija, V. (2020). Medellín’s social urbanism: Architecture and urban integration. Cities, 105, 102842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102842

- Lee, J. Y., & Ong, B. L. (2018). Biophilic urbanism in Singapore: Green strategies and planning policies. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 33, 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2018.04.005

- Rautela, P., & Khosla, R. (2019). Passive architecture in traditional Indian settlements: The case of Ahmedabad. Energy and Buildings, 183, 410–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2018.11.034

- Seguel-Medina, C., et al. (2025). Towards a landscape-based approach for planning and design in complex urban geomorphologies: A case study of Valparaíso, Chile. Journal of Urban Studies & Ecological Design. Advance online publication.

- Shifting perspectives on colonial architecture in Indonesia. (n.d.). Architecture and Education Journal. https://journals.openedition.org/abe/372

- Hashartyadi, H. (n.d.). Application of colonial architectural design to “Bandoeng”: Architectural styles in the Greater Bandung area. Journal of Design and Environment, 12(1).

Seakmy Ty

About the Author

Seakmy Ty is a Cambodian architecture student pursuing a master’s degree in urban planning in France. Originally from Phnom Penh, a city that is rapidly changing due to urban growth, she has developed a deep passion for sustainable urban design and planning. She has received academic training in smart city systems, energy efficiency, and resilience strategies. Seakmy is particularly interested in how design and governance can create cities that balance rapid development with long-term environmental and social well-being.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

Kim Dovey: Leading Theories on Informal Cities and Urban Assemblage

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “