Urban Governance in India: Between Cosmetic Decentralization and Structural Dysfunction

Despite decades of discourse on urban reforms, India’s governance frameworks continue to entrench inequality, institutional fragmentation, and civic disenfranchisement. Budgetary increases and flagship projects have been mistaken for genuine transformation, while the underlying architecture of urban power remains virtually untouched.

This article critically interrogates why India’s urban governance needs not just incremental improvements but a radical restructuring of political, fiscal, and spatial power.

1. Flawed Decentralization: More Committees, Less Autonomy

While decentralization has been a popular buzzword in India’s urban policy landscape, in reality, it has translated into the creation of multiple supervisory layers rather than the transfer of meaningful power. Urban local bodies (ULBs) often find themselves stripped of authority over key functions—transport, housing, water supply—outsourced to state-controlled parastatals, urban development authorities, or special purpose vehicles (SPVs) created under schemes like the Smart Cities Mission. This bureaucratic entanglement fosters a governance model where elected city governments are ceremonial rather than sovereign.

Moreover, decentralization without functional clarity has fragmented responsibility without accountability. Ward committees, area sabhas, and other participatory mechanisms are tokenistic in most cities—lacking funds, staff, or enforcement powers. This pseudo-participatory model undermines democratic agency while maintaining top-down control, deepening the disconnect between citizens and decision-making structures. True decentralization demands political devolution, not managerial delegation.

2. Planning without Political Economy: Technocratic Urbanism’s Limits

Urban planning in India has historically been envisioned as an expert-led technical exercise rather than a democratic negotiation of competing social interests. The consequence is an urban landscape shaped by exclusionary logics—where land use plans legitimize elite interests, and marginalized communities face systematic displacement in the name of “world-class city” visions.

The failure to integrate political economy into urban planning manifests in the persistent production of informality, spatial segregation, and socio-environmental injustices. Master Plans rarely reflect the realities of informal settlements, informal economies, or vulnerable groups; instead, they become instruments to reinforce formal land markets and sanitize the urban poor from prime real estate.

Unless planning processes are anchored in equity, redistribution, and social justice frameworks, technical ‘improvements’ in design standards or codes will continue to reinforce structural inequalities.

Further, the overreliance on private consultants and global urban models erodes local capacity-building. Imported visions like “smart cities” and “urban corridors” often ignore local contexts, histories, and ecological realities—producing alienated, unsustainable urban forms. Without democratizing the planning process, Indian cities risk becoming ever more unliveable and socially polarized.

3. Municipal Finance: The Illusion of Capacity Without Revenue Autonomy

One of the gravest failures of Indian urban governance is the persistent financial infantilization of municipal bodies. Despite constitutional recognition through the 74th Amendment, ULBs continue to lack real fiscal powers. They are dependent on piecemeal grants, state transfers, and project-based funding that prioritize capital-intensive infrastructure over systemic institutional strengthening.

This revenue dependency leads to two critical distortions: (i) city governments are disincentivized to innovate on local taxation and revenue mobilization strategies, and (ii) urban governance priorities are dictated by central and state agendas rather than grassroots needs. Stamp duties, property taxes, land value capture, user charges—critical tools for building sustainable municipal finance—are either weakly implemented or hijacked by higher levels of government.

Moreover, the push toward municipal bonds and public-private partnerships (PPPs) has introduced fiscal risks without corresponding governance reforms. Bond financing without strong local accountability and financial management capacity can deepen debt crises and erode public services. Without fiscal autonomy and creditworthiness grounded in accountable governance, urban finance reforms will remain hollow.

4. State Capture and Urban Governance: The Invisible Hand of Political Elites

Urban governance reform debates in India rarely acknowledge the systemic capture of city decision-making by entrenched political and economic elites. Key urban land, infrastructure, and services are often regulated not for public welfare, but for speculative profit and political patronage. Large-scale urban renewal projects—often framed as regeneration or redevelopment—frequently become vehicles for elite accumulation, gentrification, and mass displacement.

State governments tightly control municipal elections, delay devolution of powers, appoint unelected administrators, and manipulate urban boundaries to favor political interests. This tight state grip has produced clientelist governance models where urban reforms serve private over public interests, undermining transparency, participation, and long-term resilience.

Any serious governance reform must first dismantle the deep structures of elite capture and political manipulation that currently define Indian urbanism. Otherwise, urban development will continue to reproduce inequality, spatial injustice, and civic alienation at an accelerating pace.

5. Toward a New Urban Social Contract

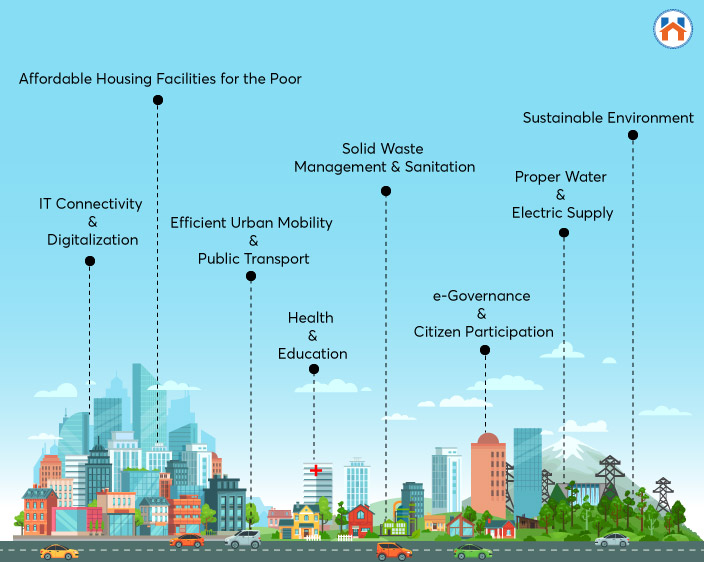

Urban governance in India requires not cosmetic tweaks, but a reconstruction of the social contract between cities and their citizens. This demands:

- Constitutionally guaranteed fiscal, functional, and political autonomy for ULBs.

- Mandatory participatory planning processes, where community needs and rights are structurally embedded in land use and service delivery frameworks.

- Robust accountability and transparency mechanisms, ensuring that local leaders are responsive to citizens, not merely higher political bosses.

- Social and spatial justice as the organizing principles of urban renewal, moving beyond the growth-obsessed model to one that centers human dignity and ecological sustainability.

Until reforms are rooted in these deeper structural shifts, India’s urban future risks becoming one of fragmented cities, privatized commons, and democratic decay masked by glittering infrastructures.

India’s urban future cannot be secured through grand infrastructure projects, decorative participatory mechanisms, or technocratic planning alone. Genuine urban renewal demands confronting the political foundations of dysfunction—rebuilding cities as democratic, inclusive, and rights-based spaces rather than treating them as investment zones or administrative units.

Without dismantling the structures that concentrate power away from citizens, reforms will remain cosmetic, deepening spatial inequalities and civic disillusionment. Urban governance must be reimagined as a transformative project that prioritizes local sovereignty, fiscal empowerment, participatory justice, and ecological resilience over short-term growth metrics.

Cities are not engineering problems to be solved; they are living polities to be nurtured. The challenge before India is not merely one of better planning or larger budgets—it is the moral and political task of restoring urban citizenship to its rightful place at the heart of governance. Only then can Indian cities evolve from fragmented infrastructures of exclusion into vibrant commons of opportunity, dignity, and collective life.

Related articles

Remembering Frank O. Gehry: The Architect Who Redrew Skylines

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

UDL Illustrator

Masterclass

Visualising Urban and Architecture Diagrams

Session Dates

28th-29th March 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “