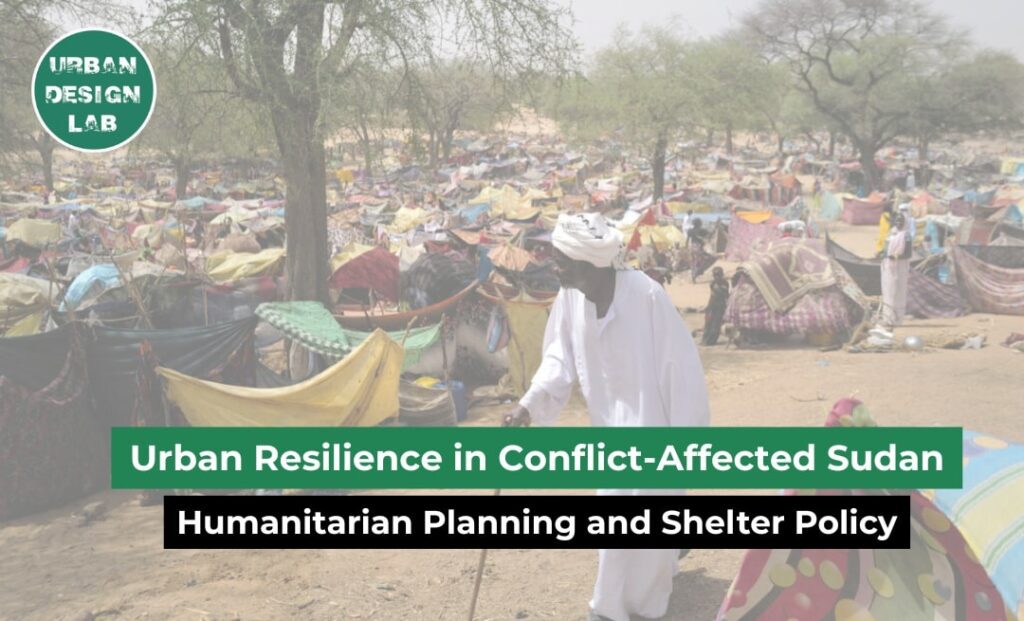

Urban Resilience in Conflict-Affected Sudan: Humanitarian Planning and Shelter Policy

This article explains how urban resilience principles can inform humanitarian shelter planning in Sudan during the ongoing conflict. Based on contemporary field reports, scholarly research, and humanitarian policy, it reflects on both the challenges as well as creative solutions that are shaping shelter provision in displacement camps. Special focus is given to communities’ coping mechanisms, the policy and governance dimension, and the spatial politics of urban displacement in cities like Khartoum and regions like Darfur.

Introduction

Since April 15, 2023, Sudan has been immersed in one of the biggest humanitarian crises due to the ongoing war between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces. In this conflict, civilians have borne the brunt of violence, being affected in all sectors, including healthcare, education, food safety, and housing. As of that date, millions of citizens have been displaced both internally to safer states and externally across borders to neighboring countries.

As the conflict continues across multiple Sudanese states, the housing crisis continues to escalate, revealing vulnerabilities in the urban fabric. It was crucial to secure a shelter that is safe, sustainable, and adaptable, not only as a short-term response, but as a long-term stability for any expected conflict that may occur. Urban resilience emerges as a framework for communities and individuals’ systems to adapt and recover from the effects of conflicts and compounded shocks.

IDP camps as a common strategy

Across the globe, many regions have been affected by conflicts and have developed different responses to prolonged instability. Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camps were the common strategy in all these regions to solve the problem of housing during conflicts. IDP camps are temporary facilities designed to offer immediate protection for those fleeing their homes due to a danger that threatens their lives, whether it is a result of a natural or man-made disaster. Although it is not considered a permanent solution, these camps should meet specific standards to function effectively, protecting the people, ensuring their dignity, and providing their basic needs. The design of the IDP camps varies from one region to another depending on political and environmental contexts, in addition to the nature of the associated disaster causing the displacement.

Urban Resilience, in this context, extends beyond shelter provision. It encompasses maintaining access to critical services, including food, water, and environmental health, that keep civilians’ lives protected during the conflict. Moreover, resilience reflects the maintenance of social and economic networks under stress, preserving livelihood, employment, and social cohesion consistency.

Source: Website Link

April 15, 2023 – War Begins

In Sudan, numerous areas were severely affected by the ongoing war, particularly in central and western Sudan. Khartoum, the capital, is where the war began in April 2023, with sudden looting and widespread destruction forcing the residents to flee for their lives. This devastation affected the city’s infrastructure, including buildings, bridges, and landmarks, triggering a massive wave of displacement; more than 8.5 million people were displaced internally, many of whom sought refuge in nearby states whose urban centers were unprepared for such a rapid population influx.

The unexpected increase in population in the safe states resulted in critical challenges, including water shortages, overcrowded and unhealthy environments, and a housing crisis. Camps, central kitchens (Takaya), and host-community-based shelter were all responsive strategies adopted by communities and humanitarian actors to overcome the situation, upholding the dignity of Sudanese people. These measures were implemented as temporary responses, but the war did not stop shortly after; it has been lasting for more than two years, and the temporary solutions were no longer adequate. As displacement becomes more prolonged, there is an urgent need to shift from emergency responses to sustainable, resilience-focused shelter planning.

Resilience in Western Sudan

In Western Sudan, the situation was different. People of Darfur have been experiencing temporary migration since the early 1980s, when the failed rains forced the farmers to adapt. Over time, they have practiced resilience in income-generating activities, engaging in diverse local sectors including crafts, small trades, and brick-making.

In 2003, an armed conflict ignited across Darfur, triggering widespread displacement movements and shattering peace among inhabitants. The people of Darfur reflected on their locally developed systems of land and water management, adapting to the circumstances they were forced to live. Many fled rural villages to the towns and urban centers like Elfashir and Nyala, building informal settlements from local materials.

In these new environments, they created a new lifestyle and adapted to it, developing new livelihoods and socializing accordingly. The experience of residing in a place they never expected to live in, and curating their whole lives according to it, emphasizes the profound level of resilience and adaptation. It highlights not only coping mechanisms but the reinvention of home after displacement.

Resilience becomes routine

As the conflicts in Darfur persisted, by the mid-2000s, the temporary camps had to be transformed gradually into permanent settlements. The displaced people have formed entire communities, comprising all age groups, in Abushouk, Kalma, and Zamzam camps, which were built by the efforts of thousands of youth groups repairing roads and water tanks, women organizing communal kitchens, and aid agencies constructing latrines and shelters. Resilience became routine; instead of collapsing, they decided to survive and rebuild their lives in a new environment.

From 2011 to 2018, the international aid funding declined, and people had to rely on themselves. Individuals revolved around themselves, supporting each other through community saving circles, new income-generating activities, and relatives’ remittances, enabling them to continue their lives in an urban context while carrying their rural identity.

However, the impact of conflict extended beyond housing to severely affect water and flood infrastructure, causing contaminated water supply and sewer systems that threaten public health and the safety of displaced people.

2023–2024 Conflict Returns

In 2023, conflicts started in the capital of Sudan, Khartoum, and once again spread westward to Darfur. This time, the people of Darfur were more prepared. In Elfashir and Geneina, old networks were activated, informal markets pivoted quickly, families hosted displaced groups in their homes, and community leaders made efforts to secure safe water. Despite the extreme destruction, the resilience developed more effective strategies. Immediately, people began to rebuild shelters, trade systems, and informal schools instead of waiting for the government to act.

In April 2024, the situation deteriorated severely when the RSF imposed a siege on El Fashir, directly targeting civilians inside their camps. In July 2024, famine was confirmed in Zamzam camp, which hosts 500,000–800,000 internally displaced people. The people of El-Fashir, North Darfur’s capital, have applied all the methods they had developed before for resilience, but the siege and food block stopped them from continuing, and the resilience was no longer enough. Now, they are experiencing a hunger crisis, and there is no room for adaptation. Today, they face a devastating hunger crisis, with no room left for adaptation.

Conclusion

Effective shelter planning should address many factors to solve problems. It should be responsive to large-scale displacement and extreme food insecurity. While resilience plays a role in adapting to emergencies as part of its framework, humanitarian planning must consider secure corridors and strong partnerships to prevent people from starvation.

Shelters must keep people safe away from conflict zones, violence, and abuse, whether it is a temporary shelter or evolving into a permanent settlement, while guaranteeing adequate space, good drainage systems, a clean water supply, and permeability to reduce floods. People in the shelters should have access to basic infrastructure, including health facilities, educational institutions, and livelihood opportunities.

Ultimately, this is a collaborative mechanism between the government, communities, and humanitarian actors to respond to unexpected crises and endure future conflicts.

References

- What are the economic and poverty implications for Sudan if the conflict continues through 2024? (2023). Google Books.

- Grum, B., & Kobal Grum, D. (2023). Urban Resilience and Sustainability in the Perspective of Global Consequences of COVID-19 Pandemic and War in Ukraine: A Systematic Review. Sustainability, 15(2), 1459.

- Young, H., & Ismail, M. A. (2019). Complexity, continuity and change: livelihood resilience in the Darfur region of Sudan. Disasters, 43(S3), S318–S344.

- Schillinger, J., Özerol, G., & Heldeweg, M. (2022). A social-ecological systems perspective on the impacts of armed conflict on water resources management: Case studies from the Middle East. Geoforum, 133, 101–116.

- Basheer, M., & Elagib, N. A. (2024). Armed conflict as a catalyst for increasing flood risk. Environmental Research Letters, 19(10), 104034.

- Ramazani, R., Ostadtaghizadeh, A., Yari, A., Hanafi-Bojd, A. A., Soltani, A., Rostami, S. B., & Heydari, A. (2022). Criteria for Locating Temporary Shelters for Refugees of Conflicts: A Systematic Review. Iranian Journal of Public Health.

- Maru, M. T. (2023). Sudan’s atrocious political transition: resolving the displacement and humanitarian crisis.

- UNHCR. (2013). What is a Refugee Camp? Definition and Statistics | USA for UNHCR. Unrefugees.org.

- Nashed, M. (2025, August 6). Why are people starving in Sudan’s el-Fasher? Al Jazeera.

Asma Alhassan

About the Author

Asma Alhassan is an architecture graduate from the University of Khartoum, Sudan, with a focus on urban design, research, and visual communication. Interested in exploring creative ways to enhance comfort and livability. She has contributed to studies on architectural and social issues and participated in fieldwork and spatial analysis. Asma brings a multidisciplinary perspective to her work.

Related articles

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “

One Comment

“Resilience became routine” — a poignant phrase to describe the reality of Sudan’s idps .