Walkability as a Sustainable Approach in Asian Cities

What is the concept of Walkability?

With the accelerating globalization and modernization of the cities, the idea of walkability was almost considered a utopian concept. The rapid increase in the urban sprawl of emerging cities made motorized transport the most convenient and appreciated mode of transit. The cities became more accustomed to it being unaware of the problems that were accumulating with the negligence of walkability.

In the current times, the developed countries have taken considerable measures to make their city walkable. The rigorous trend of making cities pedestrian-friendly continues to grow in popularity, with walkable neighborhoods growing more than twice as fast as the overall market. Although the idea of walkable cities is still quite alien to developing countries. The social dynamics of a developing country differ from a developed country, in fact, the social-cultural and economical notion of society varies and it is a significant component when analyzing the walkability index of a society. Walkability is an overarching ideology for a sustainable city, however, it cannot work on a fixed module for every city. The concern for creating pedestrian-friendly cities is no more restricted to urban planners, it has branched out and become a significant component for public health, infrastructure, psychology, climate, and geography. The impact of these variables differs from city to city, thus the article analyses the different cities located in South Asia, South-East Asia, and East Asia in order to understand the variation in approach initiated for walkability in different contexts.

Walkability in the context of Seoul, South Korea

Considered the economic, cultural, and commercial center of South Korea, Seoul is a dynamic and ever-evolving metropolis. The nation’s capital masterfully balances commercial city-centers and towering skyscrapers with deep cultural heritage and well-preserved historical sites. With a population of over 9.7 million people, Seoul offers the complete urban experience – providing access to cutting-edge innovation, research and education within carefully planned spaces that are grounded in liveability, sustainability and quality of life.

While Seoul is highly-regarded for its liveability, what can be said about the strength and depth of its walkability as an urban center? The capital is highly dense and compact, an important factor in assessing walkability and one it shares with many other Asian cities. Besides compactness, what other measures has the city and its leadership made to support the experience of walkability in its spaces and to ensure its population benefits from the positive health, social, and psychological effects associated with it?

1. Rethinking Roads – Walkable City, Seoul

In response to the growing need for highly-walkable spaces, the Seoul Metropolitan Government (SMG) introduced the Walkable City, Seoul program in 2016. With the slogan “Goodbye Car, Good day Seoul,” seeks create a network of pedestrian and cyclist friendly walkways through the reconfiguration and connection of existing roads. It seeks to create spaces in the city that are at the human-scale, are free from automobile congestion, and are highly connected. The program implements the vision within three physical interventions:

A. Urban Pedestrian Roads

Considered the economic, cultural, and commercial center of South Korea, Seoul is a dynamic and ever-evolving metropolis. The nation’s capital masterfully balances commercial city-centers and towering skyscrapers with deep cultural heritage and well-preserved historical sites. With a population of over 9.7 million people, Seoul offers the complete urban experience – providing access to cutting-edge innovation, research and education within carefully planned spaces that are grounded in liveability, sustainability and quality of life.

While Seoul is highly-regarded for its liveability, what can be said about the strength and depth of its walkability as an urban center? The capital is highly dense and compact, an important factor in assessing walkability and one it shares with many other Asian cities. Besides compactness, what other measures has the city and its leadership made to support the experience of walkability in its spaces and to ensure its population benefits from the positive health, social, and psychological effects associated with it?

B. Reconfiguring Roads

A key element of the program is the redesign of roads and roadside infrastructure to further empower pedestrian safety and comfort. It does this through what the SMG has termed “Road Diets,” or the reclaiming of lanes and reconfiguration of roadways to create wider sidewalks, increase sidewalk amenity (e.g. street tree planting, seating, ornamentation, etc.), and implement bike lanes.

In addition to road reconfiguration, Walkable City, Seoul seeks to strengthen roadside infrastructure by implementing speed warning signs and protection zones specifically for its children. Walking Street for Children is a policy documented dedicated to ensuring pedestrian spaces are well-equipped, safe, and connected specifically during peak travel times.

C. Rethinking Highways – Seoullo 7017

Deeply embedded in the Walkable City, Seoul program is Seoullo 7017, an urban regeneration project that reclaimed underutilized highways to create an elevated, green pedestrian platform in the inner-city. This project utilized a 980-meter long overpass built in the 1960s to ease congestion but was since slated for demolition. The SMG, in partnership with the renowned architecture firm MVRDV, saw this as an opportunity to repurpose abandoned urban infrastructure as a safe haven for pedestrians, elevated from urban congestion.

An integral part of the project was to design the elevated walkway as a public garden, incorporating over 24,000 trees, shrubs and flowers spanning 228 species and sub-species. The walkway also links parks, creating an urban green network in the city.

Seoul provides a key perspective in how to manage urbanization and pedestrianization in a bustling metropolis. Its projects and initiatives speak to the value of urban regeneration – the revitalization of urban spaces to adapt to the city’s evolving needs. This supports walkability by looking inwards, through the creative activation of underutilized spaces and the creation of linkages that strengthen networks within the urban experience. This puts forth an alternative to further expansionary development that emphasizes resilience and dynamism in spaces (e.g. reclamation of roads and connecting of heritage items) and a leadership that puts walkability as a priority.

.JPG)

Walkability in the context of Singapore

In less than 60 years of independence, Singapore has created a booming metropolis regarded as one of the key economic, commercial, and cultural capitals in Asia. The city-state is also highly regarded for its liveability and quality of life, according to numerous liveability rankings published. Through masterful city planning, superior infrastructure, and thought leadership, the island successfully engages in global discourse grounded in the wellbeing of its present and future residents. But how well does Singapore integrate walkability and pedestrian empowerment into its urban structure? An understanding of the city’s early urban planning visions is vital to this analysis.

A. Housing for all

In 1965, the year of Singapore’s independence from the Malaysian mainland, the city-state needed to establish an overarching vision for planning, guided by key values and principles. One of the most significant values was housing – specifically, comfortable, adequate, and well-equipped housing for all its inhabitants as soon as possible. In 1960, the Housing & Development Board (HDB) was created to realize this vision.

Over the course of the next few decades, the HDB would develop housing for Singapore’s booming population at an unprecedented rate. These housing developments took the form of clusters of high-rise residential flats built apart from the Central Area. These new towns, while purely residential at the onset, were designed to be self-sufficient and fully walkable neighborhoods.

In time, these new towns were outfitted with community centers, planned parks, ample amenities, and integrated into the complex transit network. Presently, these neighborhoods function as planned – with amenities and services accessible within a 10-15 minute walking catchment. Singapore’s vision for decentralized self-sufficient new towns merges towering skyscrapers, affordable housing, and mixed-use public spaces to create a dynamic and walkable urban context.

B. Creating a Strong Pedestrian Amenity

Outside of these new towns, Singapore builds towards walkability through investing in public amenities that create opportunities for community building, exercise, and relaxation.

In the central business district sits one of the key streets in Singapore – Orchard Road. This area is heavily commercialized and is an important meeting place for Singaporeans. Local planners empower the pedestrian in these commercial hubs by incorporating outdoor entertainment activities, lush street planting, pedestrianizing streets for special occasions, and creating underground linkages for navigability.

The walkability of Singapore is deeply linked with its overarching planning goals and values. While a desperate need for housing lay the foundation for the conception of self-sustaining and walkable new towns, a need for dynamic public commercial spaces required investment in pedestrian-friendly amenities. The walkability of Singapore is holistically implemented and thoughtfully designed. Walkability is not an afterthought relegated to specific projects but is integrated deeply into its strategic planning.

.JPG)

Walkability in the context of Chennai, India

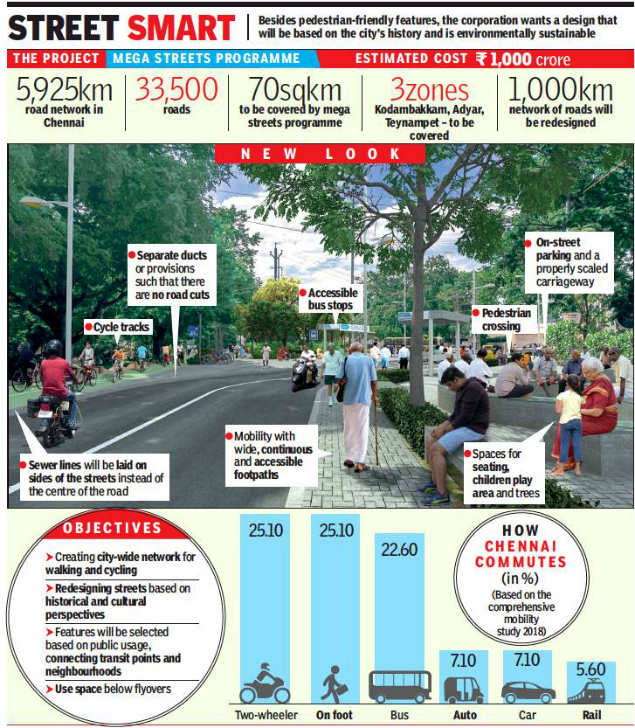

Chennai is the fifth most populated city in India, which is currently expanding at an unprecedented rate. The infrastructure and transport becomes one of the major challenges for the city, which is struggling to cater to the needs of the diverse demographic. With the city-wide traffic being an unresolvable issue, the city shifted to the improvement and accessibility of green transport. Ince 2008 several non-governmental organizations have joined hands with the authorities to design Chennai as a pedestrian-friendly space.

A. NMT infrastructure

Chennai being the economic and commercial hub of the country is designed on Euclidean base land zoning ( Residential, Commercial and Institutional). Contrary to such zoning mixed-used land zoning provides an easy walkable accessibility to multiple facilities and transit stations. The Euclidean zoning of the city makes public transport the most readily used mode of transport in Chennai. However, the prolonged commuting distance to transit stations requires walking, cycling or using intermediated transit (taxi, cabs). In 2014 Chennai became the first Indian city to adopt the NMT ( Non-Motorized Transport) infrastructure. In the following year the framework for the NMT infrastructure was designed and IPT (intermediate public Transit) was structured to provide a transit station with a proximity of 10 minutes’ walk for the neighborhood.

B. Micro-street Grid

Safety and security are often used as interchangeable terms, however when you talk about them in the context of urban planning, they refer to distinctive urban concerns. The lack of safety and security are the primary cause for reducing the walkability index of Chennai to 40 (out of 100). The poor condition of walkways and streets make the citizens reluctant to use them; the hygiene concern with the overflowing gutters, broken streets and walkways increasing risk of injuries and the lack of barriers or fences around walkways making them prone to accidents. The dead ends and lack of proper lighting contribute to the increased rate of street crime in the city, thus making the safety of walking citizens more questionable. The micro-street grid is a mapping strategy that has allowed the urban planner to focus on design and safety measures of smaller streets and by-lanes. These small streets are the primary paths for pedestrians to reach the central main street and the lack of safety and security on these streets causes a downfall in the walkability index.

C. Land Zoning

With the increase in the population of Chennai, the city is also geographically expanding, although a new zoning strategy was applied for the expansion. The city is originally designed on Euclidean land zoning which provides a segregated area for residential, commercial and institutional. A more integrated approach was taken for designing the new areas of the city, where instead of keeping those uses separate, the land was built off a combination of them in one zone. The mixed land-use zoning creates more walkable neighborhoods where multiple facilities are available at a walking distance, thus it increases the pedestrian traffic of these areas.

D. Signage

As the city of Chennai became more and more accustomed to the motorized transport system the pedestrians were marginalized, there was negligence towards proper pathways and traffic rules that cater to them. To encourage pedestrian movement around the city it is significant to introduce traffic calming devices. Introducing signage and provision on walkways and cross walk that provide better guidance for walkability. Traffic signals and signage were installed on major roads to facilitate walking and cycling.

Walkability in the context of Bangalore, India

The aggregate population of the city exceeds 10 million, making it one of the most urbanized cities of India. It was in the early 2000’s when the city realized that there was an exaggeration in problems such as, public health, air pollution, urban hygiene due to popular use of motorized transport. Though the government and organization has initiated working on green transport since then, a steep success in this attempt was observed post pandemic. The COVID situation has restricted the use of public transport, making the user rely on walking and cycling, it was that time that the citizens began to realize a significant improvement in the air quality.

A. NMT Infrastructure

The NMT (Non-motorized Transport) infrastructure of Bengaluru was initiated in 2009. It was a joint attempt of government and organization; the Bangalore City Connect Foundation (BCCF) assisted the government to redesign the Vittal Mallaya Road. It was a pilot study which received an unprecedented appreciation which led to a further redesigning project of seven other roads. Instead of working on a collective city mapping, Bengaluru focused on adding intervention to each street which made them pedestrian friendly.

B. Clean Air Street

Clean Air Street was an initiative that started in November 2020 after the pandemic lockdown was reversed. Under this initiative the Motorised traffic was banned on Church Street and opened to pedestrians, cycles, and e-scooters. The pedestrianization of the church road was a much-appreciated step, the citizens especially the women and the elderly felt an increased level of comfort and accessibility in their commuting to the church.

C. Pedestrianized Bazaar

The physical distancing protocols implemented during the COVID lockdown urged the people and the authorities to avoid overcrowding in public spaces. The government soon realized that the markets are the most crowded spaces and it is mostly due to the excessive use of vehicles. Thus, the Centre’s Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA) issued a holistic plan to make busy marketplaces pedestrian and cycling friendly. It was implemented in three markets of Bengaluru; Gandhi Bazaar, Commercial Street and Malleswaram 8th Cross.

D. Art Campaigns

Bengaluru is the only city in India where along with organization and authorities the common public also understand the importance of green transport. Eega Footpath Nammade is a citizen-led initiative through which citizens designed poster, painted murals along pathways to create awareness about pedestrian-friendly cities.

Although there are multiple components that contribute to making a city pedestrian-friendly, the most important one is to improve the quality of walkable spaces like sidewalks and footpaths. Although the problem varies in different context; to activate Seoul as a walkable city it needs to implement cycling tracks, wide walkways with amenities like planting and street furniture. The concern for a walkable street however differs in an Indian city which is the concern for hygiene: getting rid of roadside urination issues. Further the cycling tracks with the sidewalks are considered absurd considering the negligible use of it, however there is a huge emphasis on street amenities like landscaping, lightening, barrier, keeping in mind the crime rate in these cities. Therefore the basic principle remains the same but with changing social and cultural values the implementation process changes.

About the Authors

Ivanne Cheng

Ivanne Cheng is currently a student at the University of Sydney pursuing a Masters in Urbanism specializing in Urban Design. He wants to help shape cities towards becoming more thoughtfully designed, environmentally sustainable, and reflective of the needs of their inhabitants. He enjoys hiking, playing Smash Bros., Jiu-Jitsu, and giving his two dachshund dogs the attention they deserve.

Aqsa is an under graduate student at Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture, and a self-taught writer. With keen interest in urban planning and cartography. She believes that words are the fourth or the unseen dimension of a space that can enable people to connect to spaces more than ever thus aiming to empower the architecture community through her voice.

Related articles

Architecture Professional Degree Delisting: Explained

Periodic Table for Urban Design and Planning Elements

History of Urban Planning in India

Kim Dovey: Leading Theories on Informal Cities and Urban Assemblage

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “

.JPG)