William H. Whyte public space theory

Public plazas are important for the health and sustainability of cities. They’re places where people come together, socialize, rest, and enjoy their surroundings. This article looks at the work of William H. Whyte, who did research in the mid-20th century that changed how public spaces are understood and designed. Whyte used behavioral observation and time-lapse photography to study why some plazas are more successful than others. He shared his findings in his Street Life Project and the book The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces.

The article presents Whyte’s key findings in seven sections. These focus on the importance of sunlight and seating, the role of food, triangulation, and visual accessibility. It also includes a profile of Whyte himself, providing context for his methods and philosophy. His ideas about city planning are still important today. They help designers create spaces that are good for people and the environment. This article explores Whyte’s ideas and how they relate to modern design. It uses examples from New York City and mentions groups like Project for Public Spaces and Gehl Architects. His message is clear: great public spaces are not accidents—they are built by observing and respecting how people actually live.

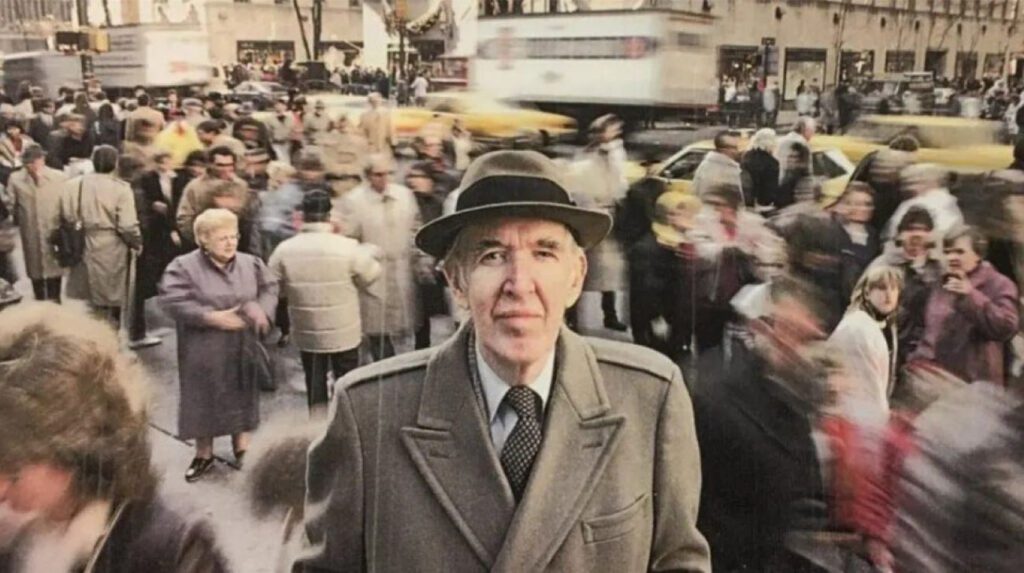

William H. Whyte: The Man Behind the Method

William Hollingsworth Whyte was a journalist and sociologist. He was one of the most important thinkers about cities in the 20th century. He was born in 1917 and started working at Fortune magazine. There, he published The Organization Man (1956), a book that criticized how companies and suburbs were changing after the war. Whyte was fascinated by human behavior, group dynamics, and social systems. These interests prepared him to contribute to urban design. In the 1960s, he joined the New York City Planning Commission and started the Street Life Project, an initiative to understand how people actually used public spaces. He thought that many problems in cities came from people not using space the right way. Whyte studied plazas, sidewalks, and parks using film, fieldwork, and behavioral mapping. Unlike many architects, he hadn’t studied architecture or planning, which may have helped him notice what others missed. He cared more about how spaces were used than how they looked. His legacy is still around today. You can find it in books and movies, but also in public places like parks where people can sit, stay, and connect with each other.

Watching the City Work: Whyte’s Research Methodology

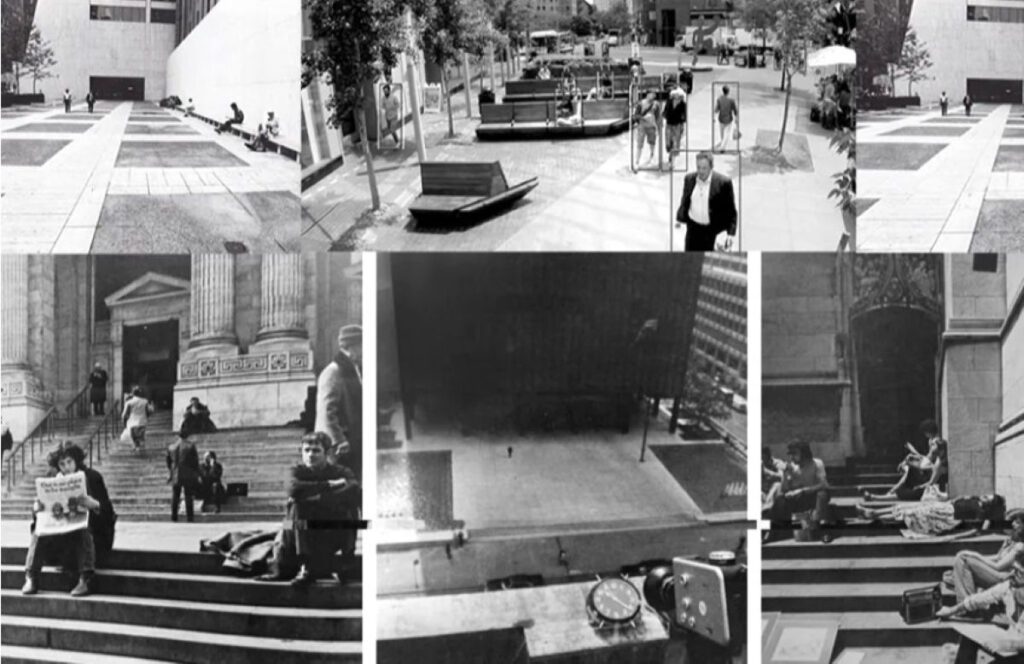

Whyte’s research method was straightforward: he used direct observation. Instead of just thinking about it, he watched how people actually acted in public plazas. Cameras were placed on rooftops and street lamps to record time-lapse videos of people’s movements, where they sat, what attracted them, and what made them leave. His team studied how people moved, grouped together, and used different conditions over time. This method, called behavioral mapping, helped Whyte learn important things about how people use space. For example, he learned that sunlight, proximity to streets, and food vendors are important. These weren’t guesses or assumptions—they were conclusions drawn from thousands of hours of visual data.

Whyte’s use of film as a research tool was especially new and different. His short documentary, The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces, is still an important work in urban studies and design education. His techniques are now used a lot in public life studies by groups like Gehl Institute. By changing the focus from the design of buildings to how people act, Whyte provided a way to make cities better through design that is based on facts—a main idea in today’s sustainable urbanism.

Source: Website Link

Access, Visibility, and Sunlight: The Foundations of a Successful Plaza

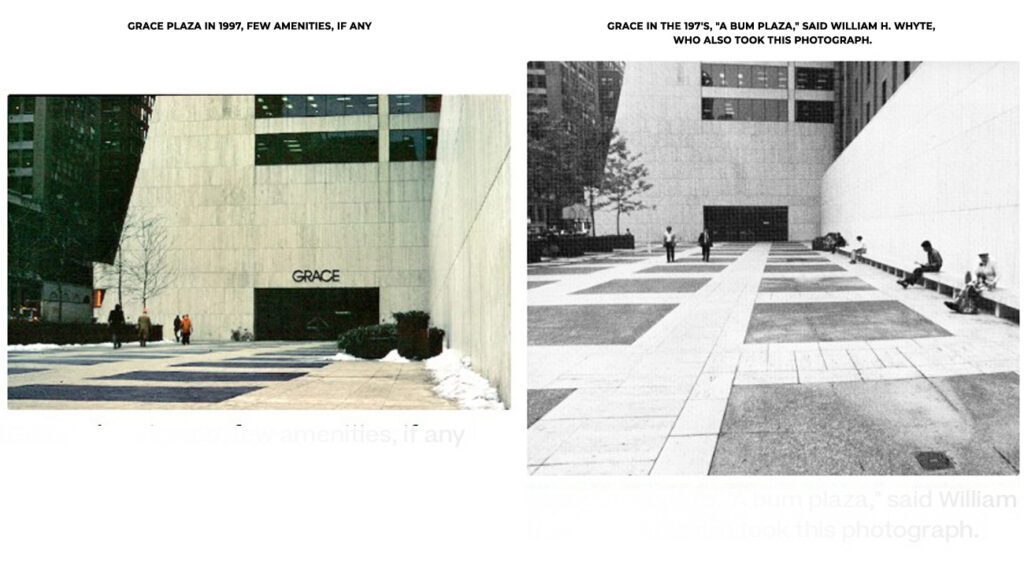

Whyte found three important factors that determine the success of public plazas: how easy they are to access, how visible they are, and whether they receive sunlight. These may seem simple but are often overlooked in urban design.

First, plazas must be accessible. Whyte found that even small barriers—like stairs, railings, or elevation above street level—significantly reduced foot traffic. People are more likely to use a space that flows naturally from the sidewalk and invites entry.

Second, visibility makes people feel more comfortable and social. Plazas should be clearly seen from the street, allowing passersby to view the activity inside. This makes spaces feel safer, more welcoming, and more lively. People are more likely to join if they see others already using the space.

Finally, sunlight matters when people choose where to sit and stay.Whyte’s footage showed that sunny areas filled quickly, while shaded or windy spots stayed empty. Designing for natural light and wind protection improves comfort and supports sustainable, energy-efficient design.

Two strong examples are Seagram Plaza and Paley Park. Their street-level access, open views, and thoughtful orientation make them lasting models of successful urban space.

The Importance of Choice: Seating as Social Infrastructure

Seating is one of the most important tools in public space design, as Whyte’s research showed. He found that the number of seats, their flexibility, and placement directly affected how long people stayed in a plaza and how likely they were to interact with others. Movable chairs were especially important because they let users control their environment. Movable seating allowed people to adjust based on sun, shade, conversation, or personal space. This independence led to longer visits, casual gatherings, and more natural use of space. Fixed benches often limited behavior and unintentionally excluded those who didn’t use the space as intended.

Whyte also emphasized incidental seating—places people sit even if not designed for that, like planters, steps, and low walls. These informal spots often became more popular than official benches because they offered variety and choice. In today’s sustainable urbanism, it’s essential to focus on how people use space and how it can adapt. Movable seating supports reuse, reduces material needs, and promotes inclusive design. Whyte’s main idea remains relevant: create inviting public spaces and let people decide how to use them.

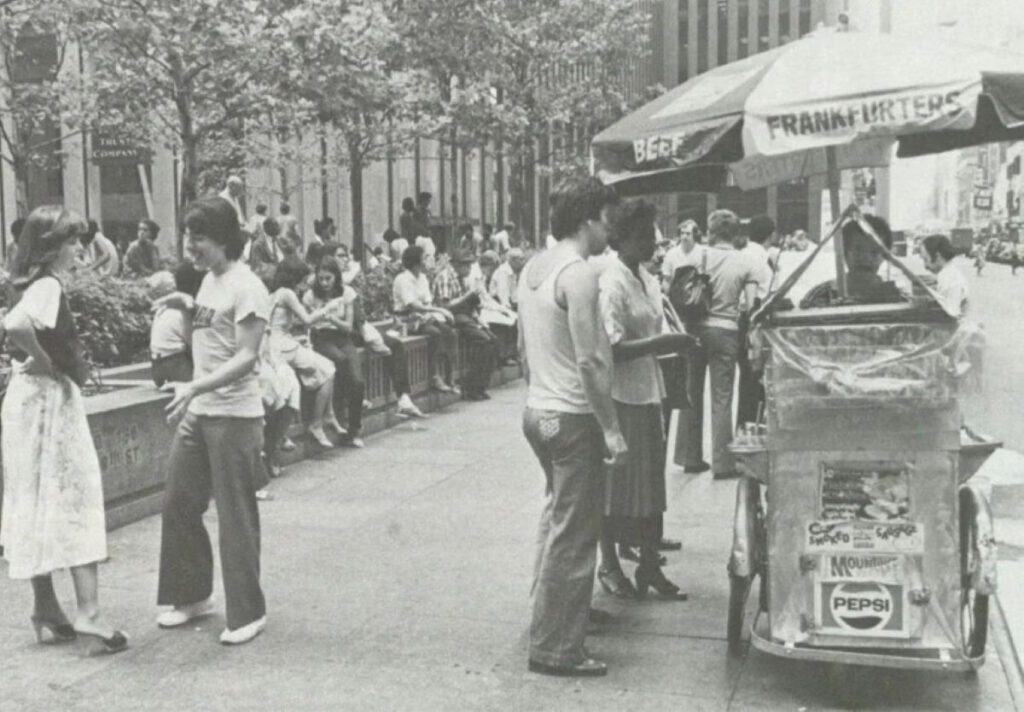

Food as a Magnet: Vendors, Cafés, and Street Life

Whyte’s thoughts on eating in public places were both practical and meaningful. He noticed that plazas with food vendors were always more lively and used more than those without. Food was a social magnet, whether it was a pushcart, café kiosk, or shaded lunch counter.

People lingered to eat. It created a routine: workers returned daily for lunch, couples met over coffee, and strangers shared tables. This simple function changed a space from a place you go through to a place you go to. More importantly, it made people feel comfortable using the space in a relaxed and social way. Whyte also talked about how mobile vendors can make space design more flexible. Rather than being fixed elements, carts and trucks could respond to pedestrian traffic and seasonal variation—making them ideal components in sustainable, low-impact urban systems.

Today, putting food into public spaces is seen as a key way to activate, promote equity, and boost economic vitality. Farmers’ markets, food trucks, and pop-up cafés not only feed people, but they also benefit the city’s social and ecological systems. In Whyte’s view, “food brings people together, and that brings more people together.” This idea continues to influence public life.

Triangulation: Designing for Fun and Socialization

Whyte came up with the term “triangulation” to describe how a third element—like an artwork, performer, dog, or event—can bring people together and spark conversation. These activities help people connect in a relaxed and comfortable way. For Whyte, triangulation was a key part of lively, democratic public spaces. He found that people are often hesitant to talk to strangers, but a shared experience—like juggling, a water feature, or a funny sign—makes it easier to start a conversation or share a laugh. These moments help build community trust, strengthen neighborhood bonds, and create emotional connections to place.

Designing for triangulation means creating opportunities for spontaneous, shared experiences. Interactive fountains, bulletin boards, games, and street performers can all encourage connection. These features are low-cost and low-energy but have a big positive social impact. In today’s planning language, triangulation refers to a place’s ability to encourage inclusion, fairness, and casual interaction. Whyte’s insight reminds us that serendipity isn’t random—it’s the result of intentional design. It grows from small details that invite people to notice, respond, and connect.

Whyte’s Lasting Influence on Sustainable Urbanism

Whyte’s work has had a lasting impact on modern urban design, especially in sustainable, people-centered planning. His observational approach laid the foundation for ideas like placemaking, tactical urbanism, and walkable cities. His insights continue to influence organizations such as Gehl Architects and Project for Public Spaces, which use his findings to improve cities worldwide.

Whyte’s core belief was that sustainability starts with usability. A space that’s environmentally sound but not welcoming to people isn’t truly sustainable. He emphasized small, replicable changes—like adding movable seating, improving sun access, or inviting food vendors—to show that social and environmental goals can align with low-impact design. He also championed equitable access to public space. His work showed that everyone—regardless of age, income, or background—deserves access to quality urban spaces. This is especially important as cities face climate change, housing challenges, and social division. Whyte redefined sustainability as more than technology—it became something cultural. He taught that sustainability is about connection, flexibility, and human dignity in everyday city life.

Conclusion

William H. Whyte is remembered for seeing things that other people didn’t see. He noticed that the best experiences in cities come from the small, everyday things that people do in public places. He studied how people sit, talk, eat, and move to understand what makes a place work. More importantly, it became a guide for building cities that focus on people instead of plans.

In a time when public life is under pressure from privatization, digitalization, and environmental problems, Whyte’s findings are more relevant than ever. He showed that successful urban spaces are not big, fancy projects—they are made up of small, thoughtful details that work well together. The key to vibrant, resilient cities is movable seating, warm sunlight, accessible food, and shared moments of joy.

As planners, designers, and citizens, we should follow Whyte’s example: look closely, listen deeply, and design with care. His question, which has stood the test of time, continues to guide future urban planning: “What do people do, and how can we help them do it better?”

References

- Gehl Architects. (n.d.). Our approach. https://www.gehlpeople.com/approach/

- Project for Public Spaces. (n.d.). William H. Whyte. https://www.pps.org/article/william-h-whyte

- Whyte, W. H. (1980). The social life of small urban spaces. Project for Public Spaces.

- Whyte, W. H. (1956). The organization man. Simon & Schuster.

- Whyte, W. H. (1988). City: Rediscovering the center. Doubleday.

Seakmy Ty

About the Author

Seakmy Ty is a Cambodian architecture student pursuing a master’s degree in urban planning in France. Originally from Phnom Penh, a city that is rapidly changing due to urban growth, she has developed a deep passion for sustainable urban design and planning. She has received academic training in smart city systems, energy efficiency, and resilience strategies. Seakmy is particularly interested in how design and governance can create cities that balance rapid development with long-term environmental and social well-being.

Related articles

Designing the Last Mile Delivery Lane to Save Urban Streets

Barcelona to Eliminate All Short-Term Rentals by 2029

UDL GIS

Masterclass

GIS Made Easy – Learn to Map, Analyse, and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

23rd-27th February 2026

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “