The role of gender in urban mobility: women right’s to the city

In terms of urban mobility, women and men move around the city in different ways. And there are important differences in the displacements performed by men and women, such as the reason for the trip, the distance of the journey, the mode of transport, attributes of the built environment, accessibility, environmental comfort, attractiveness of uses, permeability concerning the urban environment, knowledge of the route, previous experiences, and the feeling of security in the public space. A justification for such differences is rooted in the concept of gender constitutive of social and cultural relations throughout history. Gender relations have an impact on the urbanization process, affecting migration decisions, housing structures based on family roles, and community organizations. City planning can help reorganize these relationships. Therefore, a look oriented to the specificities of each gender is so important for urban planning and studies on mobility in the city (Lemos et al., 2017).

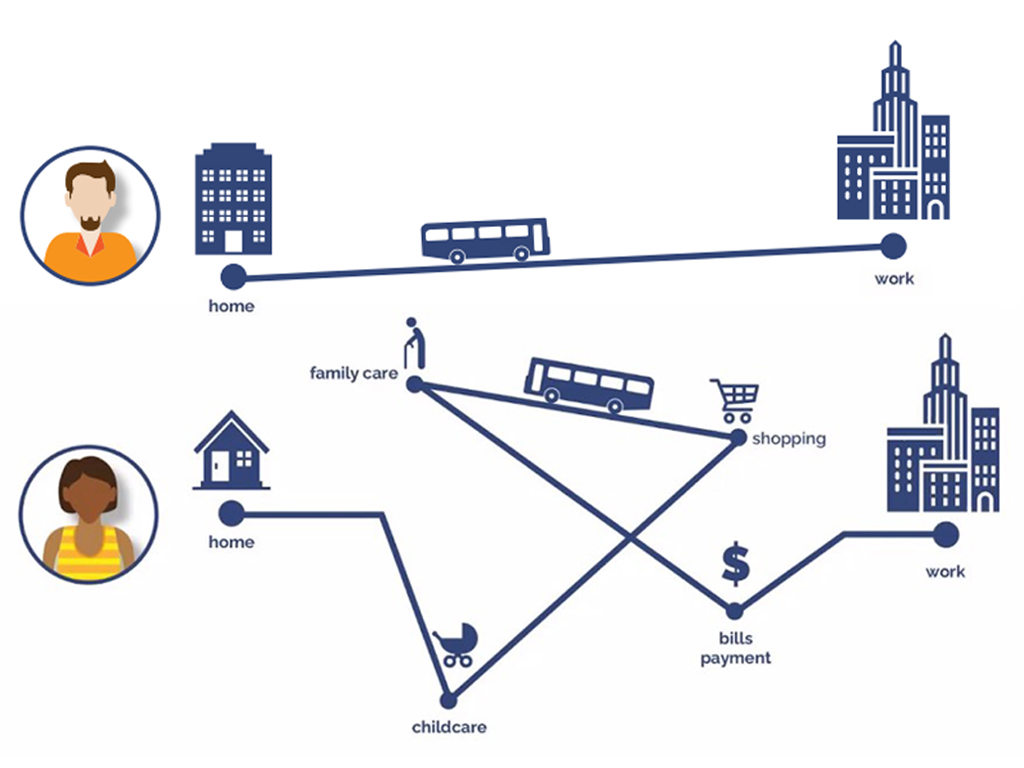

Applying a gender-sensitive lens to city planning ensures a shift to an inclusive process that pays attention to women’s opinions and needs. In the history of city development, “conventional” urban planning has frequently reflected the needs and aspirations of male urban professionals, failing to include female interests. Women are more inclined to walk and use public transportation, for example, according to studies conducted throughout the world. Because women’s travel habits are more complicated than men’s, these disparities highlight the negative repercussions of transportation design that prioritizes commuting (Zhen and Rivera, 2022).

To become gender-inclusive, a process of urban planning must use cross-cutting approaches based on major new gender and community-based data, actively include women’s views, and increase the capacity and influence of this and other underrepresented groups in decision-making (Cities Alliance, 2022). Gender-sensitive planning has shown to be a valuable approach for ensuring that all people have equal access and involvement. It takes into account the requirements of those who are frequently disregarded and encourages the development of multidisciplinary planning competence (Hanke, 2022).

From a gender viewpoint, thinking about the city entails attempting to comprehend how oppressions collect and affect women’s lives and therefore beginning to imagine viable routes for them to truly have the right to the city. This includes service, policy, and economic accessibility. In this context, there are hundreds of ways cities can work better for women. So here is a small compilation of features to be incorporated and examples of cities (that are trying or have already included them) oriented for more women-friendly urban planning:

1) Women-friendly public motorized transport

Everyone should be able to access the public transport realm freely, easily, and comfortably to use the spaces and services on offer. However, the quality of motorized public transport affects women and men differently. For example, overcrowding is a sensitive issue for women as the crowding effect is perceived as a potential risk situation, as it facilitates forms of sexual violence. In addition, the implementation of wagons, routes, and hours exclusively for women as an alternative policy to agglomeration is still not a consensus because separating men and women does not prevent harassment from continuing to occur in other spaces.

The security of the public transport system requires political will and government commitment to address gender-based violence. This also involves the participation of women and their representation in public and urban planning decisions. In this sense, to assure women’s participation in the transportation system, the BMTC – Bangalore Metropolitan Transportation Corporation (India) – engaged around 1,200 female conductors and operating staff members. The company also employed a counselor to help women deal with their problems. In addition, all employees must now attend gender sensitization training on a monthly basis. India has also resolved to punish criminals harshly throughout the country. Furthermore, they took a “eyes on the street” approach to transportation safety: seeing other women on the streets, whether working or riding the bus, helping them feel safer and more inclined to use public transit (Aloul, Naffa and Mansour, 2018).

2) Reclaim the city for pedestrians and cyclists

Everyone should move around the city safely, efficiently, and affordably to reach key opportunities and services. However, obstacles can be found not only in motorized modes of transportation but also in simple walking or cycling. A deserted street with insufficient illumination, for example, serves as a warning to women not to stroll in specific areas, forcing them to alter ways or spend more money on transportation in order to avoid conditions that are conducive to attacks and rapes. We need light!

In almost every city, cars take up more space than any other road user. Therefore, a good initiative to make the streets more women-friendly is also investing in car-free areas. This space configuration allows pedestrians and cyclists to enjoy a cleaner, quieter and safer environment. Moreover, it illustrates the potential for more effective uses of urban road space as ‘exchange space’ rather than just ‘movement space’, recognizing the social importance of streets and squares (European Commission, 2004).

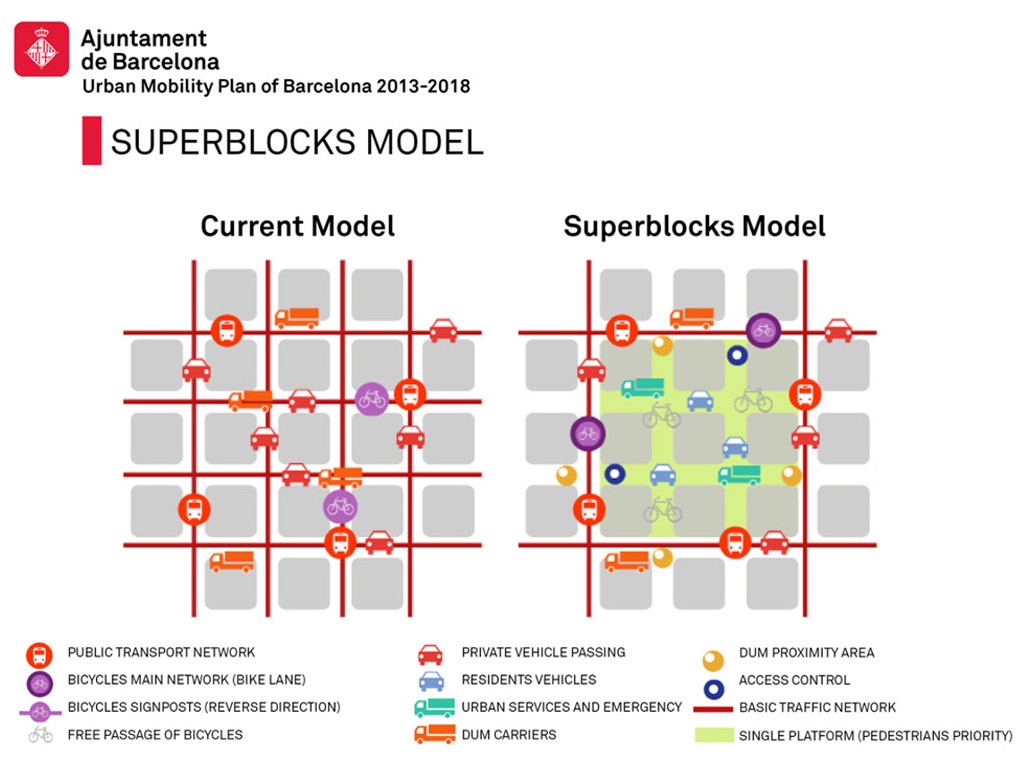

One city that has invested in the direction of prioritizing people-centric design and gender inclusion in mobility is Barcelona in Spain. Barcelona’s progress in decarbonizing transportation and transforming public space, as well as gender urbanism – where mobility must take a gender viewpoint into account. Exemplary projects in Barcelona include the ‘Superilles’, or ‘Superblocks’ concept, in which the city is pedestrianizing squares with space to relax and socialize where there was previously heavy traffic and the development of a sustainable mobility plan that promotes biking and traffic calming areas (Zhen and Rivera, 2022).

The superblocks are designed to restore urban space for people and bikes. The concept combines nine blocks into one large superblock that is blocked through traffic. Only automobiles that need access are permitted to pass, and the speed limit is lowered to 10 km/h. Instead of chaotic intersections, there are parks with picnic tables and play spaces. Barcelona has built six of them until recently. And there are plans to extend the project to over 500. The superblock project included a large portion of asking the community, particularly women, what they desired. The overwhelming response: benches. Benches are useful for more than just chatting and developing interpersonal relationships. They are a necessary component for movement, as well as for persons who are sick, disabled, or caregivers (BBC News, 2019).

3) Individuals and public spaces that represent women

Not only the benches but the design of public space itself can also be a powerful tool for bringing women into the spotlight. Monuments and street names frequently conjure up images of strong males, giving the idea that women have no place in society. In public areas, who and what is represented sends a message to all residents about what is valued and to whom it belongs. We need Visibility! The population’s variety is equally visible and represented in public areas, cultural events, art, and government and administrative communication. Citizens from marginalized groups no longer feel invisible and unheard, as if they don’t belong. Because women are equally depicted as brilliant thinkers, inventors, and leaders, young women feel inspired and empowered (Hanke, 2022). Cities all across the globe are working to create a more sustainable and equitable transportation network for everyone. Despite this, the number of women in senior positions in the transportation industry remains low, and even when in these positions, women frequently find themselves fighting the same preconceptions that made it so difficult for them to be hired in the first place. Transportation planning networks are evolving away from males traveling to work as more women join decision-making roles, and policies aimed at increasing gender equality, such as encouraging walking, cycling, and public transit, are being implemented (Zhen and Rivera, 2022).

4) Accessible and safe routes

Everyone should be free from real and perceived danger, in public and private. However, in the public sphere, the very use of public space is conditioned by the perception of security. Therefore, designs of areas that favor coexistence, places that are multifunctional and with aesthetic quality, are options to consider in an agenda for female mobility. From a gender perspective, the effects of fear of suffering violence in urban public spaces may imply not attending them, seeking alternative routes, avoiding spaces and equipment whose experience of fear is real or imaginary, or even seclusion at home, limiting women from their urban and citizen movements (such as social participation, leisure and even, in some cases, dropping out of school) (Soto Villagrán, 2016).

5) Healthy environment

Everyone should have the opportunity to lead an active lifestyle, free from environmental health risks and oriented the transition to clean energy. Buenos Aires in Argentina is moving in this direction. The city’s Climate Action Plan proposes numerous targets and environmental activities to reach by 2050. Increased bicycle use, walkability projects, and the shift to renewable energy are all examples of sustainable mobility initiatives. These initiatives are in line with the goal of transforming residents’ mobility in a way that improves their quality of life and is compatible with the goals of resilience, inclusion, and carbon neutrality (Zhen and Rivera, 2022).

The pandemic has forced us to reconsider which type of city we want to live in (França and Faria, 2021). The virus’s limits have pushed us to reconsider previously inconceivable mobility methods. It has also allowed us to examine and improve the procedure we had once started. This back-and-forth has increased our resolve to expedite the changes and policies that have been implemented in recent years in order to establish a city that provides equal access to possibilities, as we have always dreamed. During the pandemic time, cycling in the city of Buenos Aires increased significantly, climbing from 3.2 percent to 10.7 percent by the end of 2020. The city took advantage of this chance to improve pedestrian and cycling facilities, primarily by recovering roadway space that had previously been reserved for private automobiles. The “gender gap” in cycling has long been a source of contention in the cycling community. The major concern is safety; women say they don’t bike as often as males because they feel uncomfortable. Bike infrastructure of high-quality aids in closing the gender gap. The gender gap is on parity in European towns famed for their bikeways, such as Amsterdam and Paris. The current administration in Buenos Aires has expanded the city’s public bike-sharing system to include more outlying neighborhoods, giving lower-income residents a cheap and efficient mode of transportation (Zhen and Rivera, 2022).

It is the right of women to feel that the city is theirs and that they do not need to plan their movements through any symbolic or physical barriers. Also, the daily commute, access to health, education, culture, recreational facilities and services, public transportation, job openings, and other factors must be accessible to everyone through urban mobility. According to Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR): “Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each state”. As a result, mobility rights are considered fundamental rights, as people should be able to travel freely and securely from one location to another. While Article 13 does not expressly specify that efficient transportation is a human right, citizens’ right to mobility can only be realized if they have access to adequate transportation for their own safe and efficient mobility (Aloul, Naffa and Mansour, 2018).

In this context, the ability to accurately analyze the infrastructural, social, and spatial demands of women and girls in order to 1) create women-specific urban services and 2) deliver all services while analyzing them in terms of gender equality is a prerequisite for establishing a women-friendly city. These two techniques should not be viewed as alternatives; instead, they should be considered to be complementary parallel approaches. To summarize, the first step in developing a women-friendly city is to get to know the women and girls who live there and accurately assess their needs, challenges, and possibilities. In addition, women must be equally represented in local assemblies because only then they will be able to influence urban decisions as they need to actively participate in the management of the city and daily life (United Nations, 2014). Undoubtedly, cities still need to transform a lot to become women-friendly spaces so that it is possible for women to choose their way of moving and choose when and how to move and move freely.

About the Author

Tiffany Nicoli is a researcher and holds a Master’s in Architecture and Urban Planning at the Federal University of Viçosa, Brazil. She is enthusiastic about active urban mobility and passionate about urban design. She feels that social exchanges inspire her to think about possible and more human cities. She enjoys walking and cycling and is always excited to study and discover new cities.

Conclusion

References

About the author

Related articles

UDL GIS

Masterclass

Gis Made Easy- Learn to Map, Analyse and Transform Urban Futures

Session Dates

15th-19th December 2025

Urban Design Lab

Be the part of our Network

Stay updated on workshops, design tools, and calls for collaboration

Curating the best graduate thesis project globally!

Free E-Book

From thesis to Portfolio

A Guide to Convert Academic Work into a Professional Portfolio”

Recent Posts

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

- Article Posted:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Let’s explore the new avenues of Urban environment together “